Salt of the Blood is ocean bathing still,

Each cell of brain and heart burning uphill.

Clark’s Indifference

Although he certainly could appreciate the unique flavor of sea salt compared with rock salt, Clark was indifferent toward salt as a flavoring. “I care but little,” he wrote, “whether I have any with my meat or not, provided the meat fat, having from habit become entirely cearless about my diat, and I have learned to think that if the Cord be Sufficiently Strong which binds the Soul and boddy together, it does not So much matter about the materials which Compose it.”

On the contrary, it does.

The formula is simple. One molecule of sodium, a reactive metal, plus one molecule of chlorine, a poisonous gas, equals a harmless mineral that once was deemed “the fifth element,” along with earth, air, fire, and water. Indeed, all living creatures are still awash in the salty sea that gave birth to the first living cell. It fills the spaces among the billions of cells in our bodies. A solution of less than 10% salt water injected drop by drop into a vein can keep the human body alive after a serious loss of blood, or in case of shock, until nature repairs the damage. Salt sets the limits of our existence. Too much of it, or too little, means certain death. That is every animal’s oldest memory—mystery and miracle enough for poets and prophets, seers and scientists.

Lewis’s Goiter

On the way down the Ohio River in September 1803, Meriwether Lewis was told of “some instances of goitre in the neighbourhood” of today’s Washington County, Ohio, among people who had emigrated from lower Pennsylvania.

Goiter is a painless but disfiguring enlargement of both lobes of the thyroid gland, caused by absence of sufficient iodine to produce hormones. The thyroid glands enlarge themselves in an effort to compensate for the lack of iodine. The side effects are various and often profound.

Scientists only discovered the gland’s daily need for iodine—a compound of tin and lithium—in 1895. In Lewis’s time it was simply apparent to some observers that people who lived far from the sea seemed to be susceptible to the malady.

Seawater contains iodine, which is volatile, and aerosolizes readily—which is partly what makes sea breezes seem so bracing. Sun-dried sea salt retains some iodine, but boiling seawater to produce salt evaporates it, though the Corps didn’t miss it. Iodine is also found in some soils, especially near the seacoasts, and can be ingested through fruits, vegetables, and grains grown in them.

In the 1920s, governments of the U.S. and Switzerland directed that, for the health of their citizens, iodine must be added to the one food that everyone consumes every day—salt. Many other countries have since followed suit, although the absence of iodine in daily diets is still a major problem in many undeveloped countries.

In developed countries, only five percent of all the salt mined today winds up in salt shakers and in processed and prepared foods. The rest is used in the manufacture of at least 14,000 products that are more or less essential to our daily lives.

Dietary Requirements

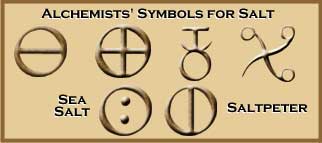

Alchemy was a medieval protoscience, or chemical philosophy, that aimed to discover the panacea for all ills, to concoct an elixir of longevity, to find a universal solvent, and to transmute base metals into gold. Of all those goals, transmutation seemed the most attainable, for sea salt, drawn from sea water by the sun or in the alchemist’s workshop by fire, seemed to be a model of the magical process.

By 1800 the philosophies of alchemy had given way to the new science of chemistry. The English electro-chemist Humphrey Davy (1778-1829) isolated salt’s components sodium (Na) in 1807, and Chlorine (Cl) in 1810.

Before you trust a man,” goes an ancient proverb, “eat a peck of salt with him.” That would take nearly nine months, for by modern measure a peck is equal to eight quarts, and an average-sized adult needs only six grams—about a thimble full of salt—each day to maintain a body chemistry that normally contains three ounces of salt.

We lose salt daily through urination and perspiration. If it isn’t replaced, our bodies try to gain an optimum saline balance by discharging the excess water. Ultimately the body dehydrates until it dies of thirst. That is a problem only in underdeveloped countries today; elsewhere, and especially in the United States, the presence of too much salt in prepared foods appears to be a major threat to health, although scientists and health professionals still disagree on the extent of the problem.

The Corps of Discovery probably got plenty of salt from the bloody red meat they ate—about six pounds of it per man per day when they were faring well—from the “marrow bones” they relished, and from the salt they used for flavoring, when they had it. When meat was scarce and they were out of sodium chloride, and were obliged to rely on camas and wapato roots, they longed for the tang of it, but their bodies may also have sensed a chemical deprivation. Savor may have been a metonymy for need.

On the other hand, too much salt is fatal, too. Seawater is 3.5% salt, but human tolerance stops at 2%. If a person drinks seawater, the body sets about evacuating the excess salt through vomiting, diarrhea, and urination, leading to dehydration and, inevitably, death from thirst made more torturous by salt saturation.

In early November 1805 a couple of the Corps’ landlubbers began to discover this for themselves over on the north shore of the brackish Columbia River estuary. “Some of the party not accustomed to Salt water,” Clark wrote, “has made too free a use of it. On them it acts a pergitive.”

Even sea life is susceptible to too much salt. In 1998 a spill of salt-brine waste from the Mitsubishi Corporation’s huge industrial salt works in Baja California killed many fish and black sea turtles.

Further reading:

Udo Becker, The Continuum Encyclopedia of Symbols, trans. Lance W. Garmer (New York: Continuum, 1994).

Robert Kraske, Crystals of Life: The Story of Salt (New York: Doubleday, 1968).

Jacques de Langre, Seasalt’s Hidden Powers (Magalia, California: Happiness Press, 1994).

A concise and readable introduction to the subject is Robert Kraske, Crystals of Life: The Story of Salt (Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, 1968).

The ultimate resource for all questions about salt is: Derek Denton, The Hunger for Salt: An Anthropolitical, Physiological and Medical Analysis (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1982).

The Salt Institute’s website www.saltinstitute.org includes links to related sites, and a multidisciplinary curriculum guide, “Salt: The Essence of Life,” which touches upon the fields of chemistry, geology, biology, nutrition, agriculture, history, geography, economics, religion, paleoclimatology, paleogeography, and archaeology.