Wintering in Mr. Jarrot’s Woods

In February 1804, the Corps of Discovery was in residence at Camp Dubois, north of St. Louis on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River. Late in the previous fall, the explorers had built their winter quarters on a 400-acre tract owned by a French fur trader named Nicholas Jarrot. The property was well timbered and full of game, and William Clark declared the location “as comfortable as could be expected in the woods on the frontier.”[2]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 2 volumes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), Vol. 1, p. 164.

The Missouri joined the Mississippi opposite Camp Dubois, and in another three months the expedition would be heading up the big river, bound for the Pacific.[3]The mouth of the Missouri has shifted four miles south since Lewis and Clark’s day, while the mouth of Wood River, where the Corps of Discovery camped, has moved north a sixth of a mile. The … Continue reading In the meantime, there was much to do in provisioning for the journey ahead. Meriwether Lewis was gone much of the winter, attending to matters in St. Louis, but under Clark’s supervision the men parched corn, rendered fat into tallow and lard, and made sugar from the sap of maple trees.

Tapping the trees and boiling the sweet, watery sap until it crystallized into sugar could begin as soon as the days warmed enough to get the sap rising in the trees. Sap dripping from a cut in the bark indicated when this was happening. In his weather journal Lewis recorded rising sap on 11 February and 13 February 1804.[4]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984–2001), Vol. 2, p. 177. All quotations or references to journal … Continue reading Tapping probably began immediately and was well underway by 20 February 1804, when he wrote in the day’s detachment orders that the:

four men . . . engaged in making sugar will continue in that employment untill further orders, and will recieve each a half a gill of extra whiskey pr. day and be exempt from guard duty.”[5]Ibid., 174.

The special consideration given the four unnamed men may suggest the importance of their work. Two months later, as the explorers were making their final preparations, Clark noted that the supplies included two bags of sugar weighing a total of 50 pounds.[6]Ibid., 203. In his field notes Clark, when listing provisions, used what appears to be the letter “w,” which may stand for “weight.” But the notation could also be … Continue reading Probably all of this was the product of their labors at Camp Dubois.[7]No known list of provisions purchased by Lewis mentions sugar.

An Early American Practice

As with most everyday tasks of the Corps of Discovery, Lewis and Clark failed to mention any details of sugar making. For these we must turn to contemporary sources. The sugaring handbook of the times, An Account of the Sugar Maple Tree of the United States, was published in 1792.[8]Benjamin Rush, An Account of the Sugar Maple Tree of the United States (Philadelphia: Aitken, 1792). Its author was none other than Dr. Benjamin Rush, the nation’s leading physician and one of the Philadelphia sages who oversaw Lewis’s pre-expedition training in the field sciences.

We don’t know if Lewis or any other member of the expedition had read Rush’s book, and it is doubtful they would have needed his instructions. Sugaring was a common practice on farms across America, and most of the men would have been familiar with the practice.

Then as now, the favored species for tapping was the sugar maple (Acer saccharum, also known as the hard or rock maple), whose range extends from New England south to North Carolina and Tennessee and west to Missouri and Iowa. The silver maple (Acer saccharinum, a.k.a. soft or white maple), red maple (Acer rubrum), and black maple (Acer nigrum) also yield sweet sap.

European Americans had been making maple sugar since learning how from woodland Indians in the 1600s, and by Rush’s day it was regarded as a patriotic way to avoid importing cane sugar from the British West Indies. Lewis’s mentor, Thomas Jefferson, believed the nation’s abundance of maple trees could meet half the world’s demand for sugar.[9]Helen and Scott Nearing, The Maple Sugar Book (New York: Schocken Books, 1971), 69. Jefferson made these remarks in 1791, when he was Secretary of State. Jefferson himself planted sugar maples at Monticello, and at his table he insisted on serving maple sugar exclusively. In 1808 he wrote, “I have never seen a reason why every farmer should not have a sugar orchard, as well as an apple orchard. The supply of sugar for his family would require a little ground, and the process of making it is easy as that of cider.”[10]Ibid. His friend and correspondent Dr. Rush declared the sugar maple a gift to Americans “from a benevolent Providence.”[11]Rush, 72.

Methodology

Rush’s book and other early documents tell us how farmers of two centuries ago—and presumably the men at Camp Dubois—went about making sugar. Start by cutting the bark with an axe, making a slanting incision one to three feet from the ground. The incision should be three inches deep and six to twelve inches wide. Next, insert a spill or “spile” into the lower end of the incision to direct the seeping sap. The spile can be a narrow shingle or a tube fashioned from an elder or sumac stem whose pith had been reamed out with a piece of wire.[12]Solon Robinson, Facts for Farmers, 2 volumes (New York: Johnson, 1866), 2:837. The sap drips into a bucket set on the ground.

Once the bucket has filled, pour its contents into a larger container—Rush mentions “troughs or large cisterns in the shape of a canoe, or a large manger made of white ash, linden, basswood, or white pine.”[13]Rush, 7. Whiskey or molasses hogsheads cut in two could also serve this purpose. We know that the expedition’s supplies included one copper and at least 14 brass kettles, and we can assume that some of these were probably used for gathering and boiling sap.[14]Jackson, 1:78 and 85.

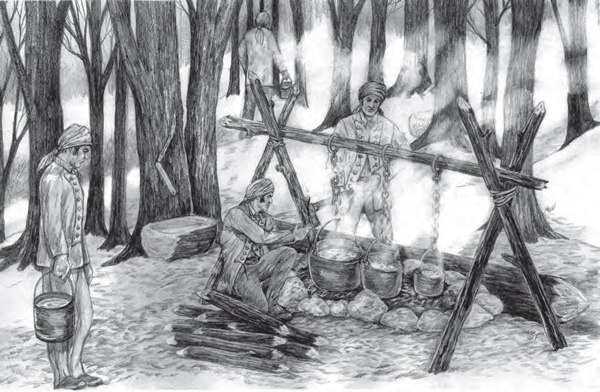

Boiling the sap took place over an open fire built against a stout back log or stone wall. The kettles were hung from a pole suspended between posts.[15]C.P. Traill, The Canadian Settler’s Guide (London: Edward Stanford, 1860), 62. A shed roof often covered the hearth, protecting it from rain, snow, or blowing ashes. Three kettles of different sizes were usually fixed in a row, the largest at one end and the smallest at the other. Freshly tapped sap was boiled in the large kettle until it thickened enough for transfer to the medium kettle, where it was boiled some more and transferred to the small kettle for rendering into a thick syrup.[16]Anonymous, in American Museum, August 1789, 100. The unknown author stated that the syrup had to reach the “proper consistency” but is otherwise not specific. Modern sources state that … Continue reading Next, the syrup was taken off the fire and partially cooled, then briskly stirred with a wooden spoon until it granulated.

Rationing Fifty Pounds

Forty gallons of sap made one gallon of syrup, which in turn converted to seven pounds of sugar.[17]These figures derive from the author’s personal experience while working for Coombs Maple Products, in Jacksonville, Vermont. If the 50 pounds of sugar recorded by Clark all came from the sugar works at Camp Dubois, the men assigned to the task might have tapped 285 gallons of sap, so we can assume there were plenty of maple trees on Monsieur Jarrot’s property. Sap runs from the first thaw until leaf budding and flows best when day and night temperatures fluctuate between 40 and 20 degrees. The season generally lasts four to six weeks. If sugaring began at Camp Dubois in mid-February, it must have continued at least until mid-March and perhaps into early April.

The 50 pounds of sugar recorded by Clark would not have been very much for such a large party (44 men when it headed up the Missouri), especially one bound on an expedition that wound up lasting more than two years. The captains must have rationed it as carefully as the whiskey. In fact, the sugar outlasted the corps’ supply of grog: the whiskey was gone by the time the explorers left the Great Falls in the summer of 1805, but when Clark tallied the remaining provisions the following December, he listed an unspecified amount of sugar still in inventory. It must have been completely consumed by September 1806, however, for as the returning explorers approached St. Louis they encountered a trader who gave them, according to Clark, “Some Buisquit, Chocolate Sugar & whiskey.”[18]Moulton, 8:363.

Indian Gifts

The journal’s few references to sugar on the trail tell us that it was used at least occasionally for Indian diplomacy. Clark states that on 12 October 1804, the captains presented gifts to several Arikara chiefs of “Sugar Salt and a Sun Glass.”

Another reference relates to Sacagawea and speaks to her feelings toward her brother, the Lemhi Shoshone chief Cameahwait, with whom she had recently been reunited after five years’ separation. On 22 August 1805, while among the Shoshones on the Continental Divide, Lewis wrote that he presented Cameahwait with some Mandan squashes, which after boiling and eating he declared “the best thing he had ever tasted,” except for a gift from his long-lost sister: a lump of Camp Dubois sugar.

Notes

| ↑1 | Patricia B. Hastings, “‘Sugaring’ at Camp Dubois”, We Proceeded On, May 2002, Volume 28, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol28no2.pdf#page=10. Patricia Hastings lives in Stevensville, Montana. As one of “The Discovery Writers” she has co-authored two books published by Stoneydale Press: Lewis and Clark in the Bitterroot (1998) and Lewis and Clark on the Upper Missouri (1999). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 2 volumes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), Vol. 1, p. 164. |

| ↑3 | The mouth of the Missouri has shifted four miles south since Lewis and Clark’s day, while the mouth of Wood River, where the Corps of Discovery camped, has moved north a sixth of a mile. The channel of the Mississippi now flows a sixth of a mile to the east of its channel of 1800. See Roy E. Appleman, “Lewis and Clark: The Route 160 Years After,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, January 1966, 8. |

| ↑4 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984–2001), Vol. 2, p. 177. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text are from Moulton, by date, unless otherwise indicated. |

| ↑5 | Ibid., 174. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 203. In his field notes Clark, when listing provisions, used what appears to be the letter “w,” which may stand for “weight.” But the notation could also be “lb.” See Moulton, 2:202n4. |

| ↑7 | No known list of provisions purchased by Lewis mentions sugar. |

| ↑8 | Benjamin Rush, An Account of the Sugar Maple Tree of the United States (Philadelphia: Aitken, 1792). |

| ↑9 | Helen and Scott Nearing, The Maple Sugar Book (New York: Schocken Books, 1971), 69. Jefferson made these remarks in 1791, when he was Secretary of State. |

| ↑10 | Ibid. |

| ↑11 | Rush, 72. |

| ↑12 | Solon Robinson, Facts for Farmers, 2 volumes (New York: Johnson, 1866), 2:837. |

| ↑13 | Rush, 7. |

| ↑14 | Jackson, 1:78 and 85. |

| ↑15 | C.P. Traill, The Canadian Settler’s Guide (London: Edward Stanford, 1860), 62. |

| ↑16 | Anonymous, in American Museum, August 1789, 100. The unknown author stated that the syrup had to reach the “proper consistency” but is otherwise not specific. Modern sources state that the optimum temperature for converting the syrup into sugar is 238 degrees. |

| ↑17 | These figures derive from the author’s personal experience while working for Coombs Maple Products, in Jacksonville, Vermont. |

| ↑18 | Moulton, 8:363. |