After Lewis’s preliminary sketch, many have contributed to the process of illustrating the Great Fall of the Missouri—Lewis’s sublimely grand fall.

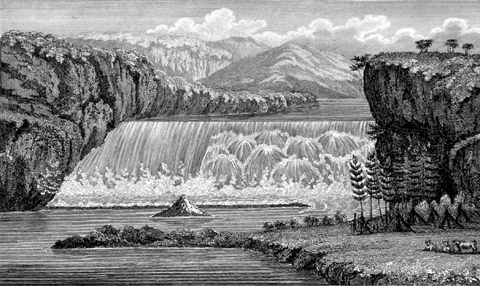

Principal Cascade of the Missouri

Courtesy of Watzek Library, Lewis & Clark College, Portland, Oregon

Engraved from a drawing by John James Barralet (1807)

Lewis’s Preliminary Sketch

After Lewis finished describing the Great Falls, he lamented that his words failed to do justice to the scene. He “wished for the pencil of Salvator Rosa or the pen of a Thompson,” in order that he “might be enabled to give to the enlightened world some just idea of this truly magnifficent and sublimely grand object;[1]Throughout the 18th century and well into the 19th the grand and the sublime were qualities one dreamed of encountering somewhere in nature’s scenery, sometime. It would be a peak experience. … Continue reading

As the British critic Lord Henry Home Kames had written, there was “a real, though nice, distinction between these two feelings”—between grandeur and sublimity. The distinction was a matter of literary expression, of mastery of style. To illustrate, he compared a passage from the Iliad as a simile for grandeur with one from Milton for sublimity. Meriwether Lewis recognized them both, and he knew when he was in their presence. The right side of the Great Fall was grand; the left was sublime.[2]Kames, Elements of Criticism (Dublin: Charles Ingham, 1772), 128-129; Google Books. . . . but this was fruitless and vain.” So, he concluded:

I therefore with the assistance of my pen only indeavoured to trace some of the stronger features of this seen by the assistance of which and my recollection aided by some able pencil I hope still to give to the world some faint idea of an object which at this moment fills me with such pleasure and astonishment, and which of it’s kind I will venture to ascert is second to but one in the known world.

His phrase “second to but one in the known world” could only have been a reference to Niagara Falls, between Lakes Erie and Ontario, near Buffalo, New York.[3]For comparison, see Niagara Falls by Fr. Louis Hennepin and Niagara Falls by Karl Bodmer (1809–1893).

On 16 July 1806, Lewis and his three companions, en route from White Bear Islands to explore the upper Marias River, paused at the “handsom fall”—now Rainbow Falls. That night they camped under the “shelving rock” in the “little wood” below the “grand falls” . . . after evicting two bears from the premises. The falls, Lewis noted as he sketched the scene, “have abated much of their grandure since I first arrived at them in June 1805, the water being much lower at prese[n]t than it was at that moment, however they are still a sublimely grand object.” He arose early the next morning and made a second drawing of the falls before proceeding on to the Marias River.

Barralet’s ‘Pencil’

Upon his return to Philadelphia in 1807, Lewis hired an “able pencil,” John James Barralet for forty dollars to make “two Drawings water falls.”[4]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1873-1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:463n. Barralet (c. 1747-1815) emigrated to … Continue reading Lewis probably showed the artist his own sketches of the “stronger features” of the grand falls and did his best to refine the details verbally, striving to recapture the essence of the “sublime” he had recognized in the scene.[5]Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806), defined “sublime” simply as “lofty or grand style.” An engaging essay on the history of this … Continue reading

On 26 January 1810, Clark wrote to William D. Meriwether that he was in Philadelphia “serching for the Materials left in this City by the late Govr. Lewis, reletive to our discoveries on the Western Tour.” Among his findings he mentioned “imperfect drawings & made of the falls of the Missouri, & Columbia.”[6]Jackson, 2:490. It is not clear whether he had in mind Barralet’s drawings, or Lewis’s and perhaps his own sketches. If the former, that might explain why Barralet’s illustrations were not included in the 1814 Biddle-Allen edition of the captains’ journals. Indeed, compared with Salvator Rosa’s depiction of a waterfall, or G. Beck’s 1802 painting of the Great Falls of the Potomac River, Barralet’s effort appears coarse and graceless. In any case, none of the original copies of any of the drawings have yet been found.[7]An undated note of Clark’s, to which Jackson referred in connection with a letter from Nicholas Biddle to Clark dated 7 July 1810, reads: “The two Drawings of the Falls of the Columbia … Continue reading

Barralet’s picture, “Principal Cascade of the Missouri,” appeared only in the Irish reprint of the History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clarke published in Dublin in 1817.[8]Stephen Dow Beckham, et al, The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 156. Since Bradford and Inskeep underwrote that printing, it may be that the American publisher urged the inclusion of the Irish artist’s work.

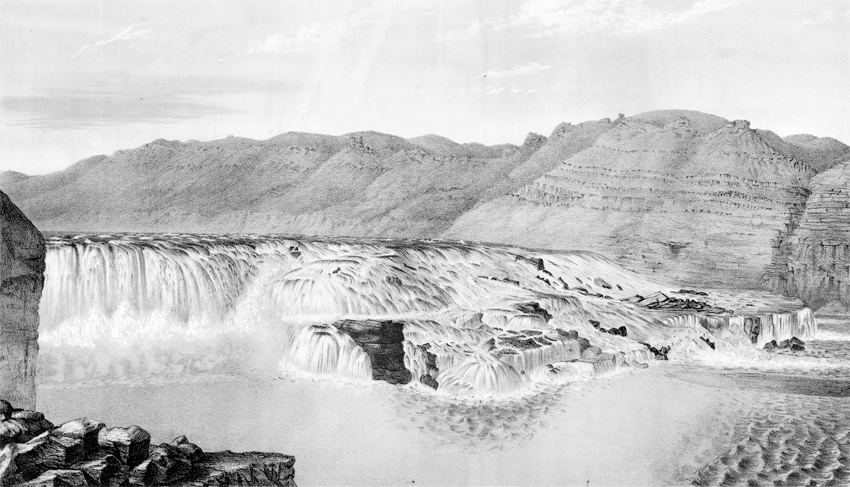

Sohon’s 1853 Lithograph

Great Falls of the Missouri

by Gustavus Sohon (1853)[9]Isaac. I. Stevens (1818-1852), Narrative and final reports of explorations and surveys to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi river to the Pacific … Continue reading

Many of the figures whose names we summon to flesh out the story of the Lewis and Clark expedition may seem to have lived for no other purpose, when in fact their own stories are varied and interesting. Such a man was Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903). Born in the city of Tilsit, in today’s Lithuania, near the Baltic Sea, Sohon emigrated to the U.S. in 1842, at the age of seventeen, and began working as a bookbinder. He was also a talented artist, as well as a gifted linguist. In 1852, having easily learning several Indian languages, he began a five-year enlistment in the U.S. Army as an artist and interpreter on several government-sponsored expeditions, most notably the one led by Isaac Stevens in 1853-1855 to locate potential railroad routes to the Pacific Coast. In 1862, he was called to Washington, D.C. to assist in the completion of the official report of the Stevens survey. After military service he operated a photographic studio in San Francisco for two years (1863-1865), then returned east to carry on a show business in Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, Sohon’s hand-tinted lithographs of Western scenes remained an important basis for popular perceptions of the Far West.

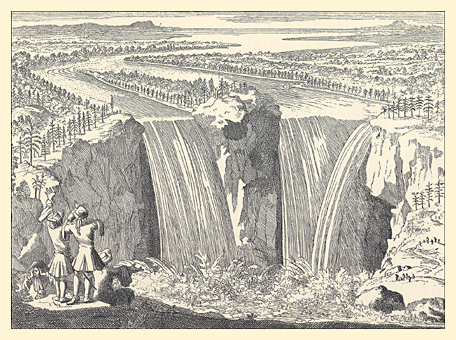

Mathews’ Exceptional Perspective

Great Falls of the Missouri

Lithograph by A. E. Mathews[10]A. E. Mathews (1831-1874), Pencil Sketches of Montana (New York: published by the author,1868), Plate XXIV.

Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula

The sketch, Mathews wrote, “was made from the left-hand bank, which has rarely been visited by white men. The artist crossed the river below the falls on a small log raft, at eminent peril of being dashed by the furious current against some of the many sharp rocks with which it is filled. On either side of the Missouri there are long Buffalo trails, worn in many places into gullies, leading from the praries at the foot of the distant mountains to the river. Since the extensive travel on the Helena and Fort Benton road, Buffaloes are becoming scarce in this part of Montana.”[11]The road Mathews referred to was part of the Mullan Road, a federal project begun in 1859 and completed in 1862 under the direction of Lieutenant John Mullan, of the U.S. Army’s Corps of … Continue reading

Alfred Edward Mathews (1831-1874) emigrated to the U.S. from England to become an itinerant bookseller and artist. After serving in the Civil War he headed west, producing some of the earliest views of Texas (1861), Colorado (1866 and 1870), and Gems of Rocky Mountain Scenery: Containing Views Along and Near the Union Pacific Railroad (1869).

The technology basic to the science and art of photography evolved during the 18th and early nineteenth centuries. In 1816 a French scientist combined the camera obscura with photosensitive paper, and after ten more years of experimentation finally produced a permanent image. In 1837 Louis Daguerre successfully demonstrated his invention, by which a copper sheet coated with silver iodide was “exposed,” and then “developed” with warm mercury. The Daguerreotype was displaced in 1851 by the new and cheaper wet plate collodion process, which permitted unlimited reproductions, and which prevailed until George Eastman perfected a dry-plate process in 1879.

In his introduction to Pencil Sketches of Montana, Mathews expressed a conservative view on the aesthetics of outdoor photography:

The author has frequently been asked why he did not take a Photographic Instrument along, in order to photograph Mountain scenery; for it is generally supposed that a photograph of Mountain scenery is always perfectly accurate. This, however, is far from being the case. In taking a picture, the lens of an instrument must be adjusted to focus on a certain object or objects; and all others more distant, or nearer, will be more or less indistinct. Another disadvantage of an instrument is that objects near at hand are magnified, while those farther off are reduced in size. So apparent is this defect in large photographs of persons that a small picture is now first taken, and afterwards copied and enlarged. Shadows, too, are apt to be deepened and lights intensified. A good artist can, with ordinary care, produce a more accurate and pleasing picture with the pencil or brush.

Fundamentally, Mathews’ objection is still valid. The human eye, linked to the brain, is of course subjective, and thus selective; the camera lens, reacting only to light within the range of its own inanimate eye, is objective and comprehensive. However, during the twentieth century the medium became so integral a part of everyday life, worldwide, that its optical illusions are now tacitly accepted as realities.

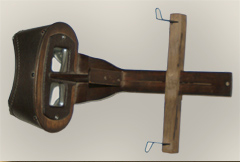

F. Jay Haynes’ Stereo Photo

As far as we know, Frank Jay Haynes was the first photographer to capture the Great Falls of the Missouri. Haynes shot this view with his twin-lens stereographic camera. A special hand-held stereo viewer, called a stereoscope, is necessary to see the 3-D effect.

A stereoscope,” explained Oliver Wendell Holmes, “is an instrument which makes surfaces look solid. All pictures in which perspective and light and shade are properly managed, have more or less of the effect of solidity; but by this instrument that effect is so heightened as to produce an appearance of reality which cheats the senses with its seeming truth.”[fn]Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” The Atlantic Monthly, 3 (June 1859), 738 .48.[/fn] The instrument was invented in England in 1838.

Photographer F. Jay Haynes stands beside his stereographic camera at the “handsom Fall” in 1880. The shutter was a hinged device in front of the twin lenses, operated by hand. His portable darkroom is probably on a nearby wagon.

Although the huge herds of bison were absent, the rattlesnakes were still numerous, so Haynes prudently carries a six-shooter under his belt for self-defense.

On 12 July 1860 Captain William F. Raynolds and a five-man detail from the Missouri River contingent, visited the falls of the Missouri, with Biddle’s edition of Lewis and Clark’s journals in hand. “Their description is remarkable for its vividness and accuracy,” Raynolds found, “and as I passed down I compared it point by point with the scene before me, verifying it in every essential respect.” Early the next morning, the expedition’s topographer and assistant artist, J. D. Hutton, set out with two assistants to take a photograph of the Great Falls. He returned at nightfall, according to Raynolds, “having indifferently accomplished the object of his expedition.”[fn]W. F. Raynolds, Report of the Exploration of the Yellowstone River (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1868), 109.[/fn] Since no such photograph has yet been found, we may assume it wasn’t worth keeping.

Experiments that ultimately led to the invention of the camera as we know it began early in the 1700s and steadily gained momentum through the opening decades of the nineteenth century. In 1816 the first successful attempt to combine the camera obscura—the instrument Lewis wished he had brought along—with photo-sensitive paper. By 1839 the Daguerreotype camera, which captured images on chemically prepared copper plates, made photographic portraiture an important commercial enterprise.

Wet-plate technology, perfected in 1851, added impetus to the ever-widening popularity of photography as a documentary and artistic medium.[12]The George Eastman House Timeline of Photography, www.eastman.org/5_timeline/1849.htm (Link expired) A glass plate coated with light-sensitive collodion produced a negative image from which multiple paper positives could be made.

The plate had to be exposed immediately after the collodion was applied, and promptly fixed with chemicals, which required a light-proof darkroom. The technology was tedious, undependable by today’s standards, and the heavy equipment it required made an indoor studio the most practical operating venue. That may have been the reason for J. D. Hutton’s “indifferent” results. Only a skillful photographer with infinite patience, great physical endurance, a crew of dedicated helpers and a superior good luck, could venture far afield. Frank Jay Haynes was just such a person.

Meanwhile, in 1877, while wet-plate photography was still at the height of its development, and stereography (3D photography), which had originated in 1841, was increasing in popularity, Haynes set up a studio at Fargo, in Dakota Territory. Three years later, he and a crew of seven assistants set out on a 1,200-mile picture-taking excursion up the Missouri River, photographing key points along the route, all the way to the falls. Their supplies and equipment, including a light-proof tent for a darkroom, filled two horse-drawn wagons.[fn] Untitled typescript page by Jack E. Haynes, son of F. Jay, in Vertical File “Frank Jay Haynes,” Montana Historical Society, Helena.[/fn] “This trip,” he wrote to his wife, Libby, “is going to be worth a fortune to me for it is going to open up a new field.”[fn]Edward W. Nolan, Northern Pacific Views: The Railroad Photography of F. Jay Haynes, 1876-1905 (Helena: Montana Historical Society, 1983), p. 38. In 1881 Haynes became the official photographer for the Northern Pacific Railroad, and soon became famous for his popular stereographs of scenes in Yellowstone National Park. In the mid-eighties he switched to George Eastman’s revolutionary new dry-plate process.[/fn] Haynes returned to Fargo late that summer with historic photos of both the “beautiful cascade,” otherwise known as “handsom fall,” and that “sublimely grand object,” the Great Falls of the Missouri. At long last the world could share Meriwether Lewis’s “pleasure and astonishment”—in stereovision!

“Sublimely grand specticle”

This is one of the earliest existing photographs of the Great Falls, taken from the point at the edge of the high prairie where Lewis may have made his difficult descent for his closeup study of the scene.

F. Jay Haynes (1853-1921) was an important early photographer of Western scenes and people. He shot this photo just a few months before a pioneer settler and entrepreneur named Paris Gibson rode his horse from Fort Benton, forty miles downriver, to see the sight he had read of in a reprint of Nicholas Biddle’s edition (1814) of the Journals of Lewis and Clark. He was inspired by the potential for industrial development of the falls, and envisioned a day when “water power could be shipped across the land by means of electricity.” Two years later Gibson founded the city of Great Falls, Montana, a few miles upstream near Black Eagle Falls, the last of the five cataracts Lewis discovered. Within another decade Great Falls gained the nickname “The Electric City.”

1888 Century Illustrated

“Great Falls of the Missouri”[13]Eugene V. Smalley, “The Upper Missouri and the Great Falls,” The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol. 35 (New Series 13), No. 3 (January 1888), 415.

Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula.

In the fall of 1888 the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, one of the leading literary magazines of the second half of the 19th century, sent a writer and an artist out west to make a trip down the Missouri from Helena, Montana, to the falls and Fort Benton. As a guidebook they evidently carried a reprint of Nicholas Biddle’s paraphrase of the Lewis and Clark journals.[14]Fewer than 1,500 copies of the original Biddle-Allen 1814 edition of the journals were printed. However, Harper and Brothers, of New York, republished the Dublin 1817 edition of Biddle’s … Continue reading

Viewing the Great Fall from the heights on the south side, the writer observed:

We could only see the entire breadth of the fall from a single point on the extreme verge of a crag jutting over the cañon. There was no way of getting down into the gorge to the water’s edge, which is about four hundred feet below the general level of the country. The deep crease in which the river runs is entirely lost to view a quarter of a mile away. Its lips seem to close up, and appear like the many modulations in the grassy plain, so that a traveler riding across country might come almost to the sheer verge of the cañon before he would suspect that he was approaching one of the great rivers of the world.

Wheeler’s Centennial View

Centennial Portrait of the Grand Fall

Photographer unknown; ca. 1901.

“The Great Falls of the Missouri,” Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

Olin Wheeler (1852-1925) was the first author to produce any significant works about the Lewis and Clark expedition. His major contribution to the literature was The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904; with a description of the old trail, based upon actual travel over it, and of the changes found a century later[15](2 vols., New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904). Wheeler’s importance in the historiography of the expedition is briefly discussed in Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and … Continue reading. Appearing in 1904, just eleven years after Elliot Coues’s meticulously annotated reprint of Biddle’s paraphrase, and a year before Reuben Gold Thwaites’ similarly thorough transcription of all the original journals then known to exist, Wheeler’s book brought to a wider public his personal impressions of the story of the expedition, the waters they navigated and the land they traversed. Among the two hundred illustrations it contained were numerous views of important expedition scenes and landmarks photographed by the various professional lensmen who accompanied him in his retracings of the route. (See Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.)

Unfortunately, the identities of only a few of those photographers are known, including L. A. Huffman of Miles City, Montana, who was a protégé of F. Jay Haynes. A few images are in the Edward Ayer Collection at the Newberry Library in Chicago, but an intensive search for original prints or negatives of the remaining photos included in The Trail has been fruitless.

Notes

| ↑1 | Throughout the 18th century and well into the 19th the grand and the sublime were qualities one dreamed of encountering somewhere in nature’s scenery, sometime. It would be a peak experience. Descending the Ohio River on the morning of 15 September 1803, Lewis passed the beautiful Blennerhasset Island, a then-well-known landmark that since 1798 had been the home of Harman Blennerhassett (who was soon—in 1805—to be the principal co-conspirator in Aaron Burr’s plot to foment a rebellion against the United States). Fortescue Cuming later drew attention to the island in his Sketches of a tour to the western country (1810). But there was something lacking. It was, he said, “a situation perhaps not exceeded for beauty in the world.” However, it needed “the variety of mountain—precipice—cataract—distant prospect, &c. which constitute the grand and sublime.” The Monthly Anthology, and Boston Review, Vol. 7 (1 September 1809), 7. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Kames, Elements of Criticism (Dublin: Charles Ingham, 1772), 128-129; Google Books. |

| ↑3 | For comparison, see Niagara Falls by Fr. Louis Hennepin and Niagara Falls by Karl Bodmer (1809–1893). |

| ↑4 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1873-1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:463n. Barralet (c. 1747-1815) emigrated to the U.S. from Ireland in 1795 and eventually set up shop at Eleventh and Filbert Streets in Philadelphia. |

| ↑5 | Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806), defined “sublime” simply as “lofty or grand style.” An engaging essay on the history of this Enlightenment-era concept is Albert Furtwangler’s “The American Sublime,” in Acts of Discovery: Visions of America in the Lewis & Clark Journals (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 23-51. |

| ↑6 | Jackson, 2:490. |

| ↑7 | An undated note of Clark’s, to which Jackson referred in connection with a letter from Nicholas Biddle to Clark dated 7 July 1810, reads: “The two Drawings of the Falls of the Columbia and Missouri are in the possession of Mr. Murray and Mr. Lawson Engravers . . . Mr. Lawson lives in Pine Street between 8th and 9th Streets. Mr. Lawson will direct Mr. Clark to Mr. Murray.” It is likely that this reference is to Clark’s diagrams of the two falls, which Biddle included in his edition of the journals. Jackson, 2:554. |

| ↑8 | Stephen Dow Beckham, et al, The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 156. |

| ↑9 | Isaac. I. Stevens (1818-1852), Narrative and final reports of explorations and surveys to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi river to the Pacific Ocean. . . . made under the direction of the secretary of war in 1853-5; Volume 12 of the Pacific Railroad Surveys (Washington, D.C.: Beverly Tucker, 1855), Plate 9. About 53,000 copies of this book were published, thus widely disseminating some of the first visual impressions of the Northwest, including the route followed by Lewis and Clark. Howard R. Lamar, ed., The New Encyclopedia of the American West (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 915. |

| ↑10 | A. E. Mathews (1831-1874), Pencil Sketches of Montana (New York: published by the author,1868), Plate XXIV. |

| ↑11 | The road Mathews referred to was part of the Mullan Road, a federal project begun in 1859 and completed in 1862 under the direction of Lieutenant John Mullan, of the U.S. Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers. The 624-mile wagon road provided the first travel route across the Rocky Mountains for emigration and commerce between Fort Benton, Montana and Walla Walla, Washington, the upper terminals for steamboats on the Missouri and Columbia Rivers, respectively. The effect of the Mullan Road on the bison population of the plains was minor in comparison with other factors, such as the bison-robe trade, and the penetration of the plains by railroads in the 1870s and ’80s. See John Mullan, Report on the Construction of a Military Road from Fort Walla-Walla to Fort Benton, 1863 (reprint, with introduction and notes by Kimberly Rice Brown, Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1994). |

| ↑12 | The George Eastman House Timeline of Photography, www.eastman.org/5_timeline/1849.htm (Link expired) |

| ↑13 | Eugene V. Smalley, “The Upper Missouri and the Great Falls,” The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol. 35 (New Series 13), No. 3 (January 1888), 415. |

| ↑14 | Fewer than 1,500 copies of the original Biddle-Allen 1814 edition of the journals were printed. However, Harper and Brothers, of New York, republished the Dublin 1817 edition of Biddle’s paraphrase twenty or more times between 1842 and 1901, mostly in runs of 250 copies. Abridged, with an introduction and linking commentary, by Archibald M’Vickar, it was featured in the popular Harper Family Library. Each included Clark’s diagrams of the “Principal Cascade of the Missouri” and “The Falls and Portage,” his map of the entire route, and Barralet’s drawing of the “Principal Cascade of the Missouri.” Stephen Dow Beckham, The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland: Lewis and Clark College, 2003), 160-61. Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 64. |

| ↑15 | (2 vols., New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904). Wheeler’s importance in the historiography of the expedition is briefly discussed in Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 226-227; also Stephen Dow Beckham, The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland, Oregon: Lewis & Clark College, 2003). |