Editor’s Note—The following was written to supplement three We Proceeded On articles on the birds of Lewis and Clark. All three are also offered on this website. The concepts presented here apply not only to birds, but the taxonomic classification of all living things.

New animals or plants of any kind are known by just one name in English or any other language. Those that are found all across the continent—or on several continents—have usually acquired a whole ragbag of folk names over the centuries. Lewis and Clark often used more than one name for the same species, and you still hear an assortment of folk names when people from different areas get together to talk about birds. You can be sure of identity only by checking with a Latin label.

Latin, a Universal Language

The use of Latin as an universal language goes back to the days of the Roman Empire. Any report, any document of any kind even from the farthest outpost, had to be written in Latin. All official business was conducted in Latin and provincials who hoped for promotion had to learn to speak the conquerors’ language fluently. As a result, when the Roman Empire finally faded, the emerging independent countries from northern Europe to the Middle East shared Latin as a ready-made international language for the exchange of diplomacy and scholarship. The diplomats eventually relied on other tongues, but even into the 18th-century most European universities conducted classes in Latin and most scholarly texts were in that language through the 16th-century. Even when authors began writing in modern languages, they continued to use old Latin (or Latinized Greek) names for plants and animals and to coin names for newly discovered species in Latin also.

Linnaean System with Binomials

But in coining new names—or applying old ones—each writer was free to follow his own choice. No central authority existed to rule that a name once published had to be kept for that species only. Also, each name usually consisted of three or four words—often five or six or even more—making them very difficult to remember. Each college professor, each director of a museum, chose these many-worded labels to suit himself, seldom agreeing with any other authority. So every time a student used a different text or studied under a new teacher, there was a new set of “right” names and classifications to learn.

In 1758, the great Swedish classifier Carl Linnaeus urged every scientist to give up this confusing hodgepodge and join him in using a universal and simplified system of classification. He had once used those long labels, too, but now had just published a new text re-naming every plant and animal he knew with a two-word Latin label. Two words—a binomial—for everyone to use, he urged. Also, he asked others to adopt his own precise definitions for each step of classification.

Everyone agreed he had a great idea—but most authorities wanted the world to adopt their label and definitions, not those of Linnaeus. So it was over a century before world scientists finally met and agreed to use the Linnaean system and his binomials of 1758, plus whatever changes were required by new knowledge. So, as Linnaeus suggested, we still use the Latin term species for an individual kind of plant or animal exactly like no other. Those species which are much alike are placed together in a group called a genus—which is Latin for kind or sort—and science still uses the Latin plural genera, not genuses.

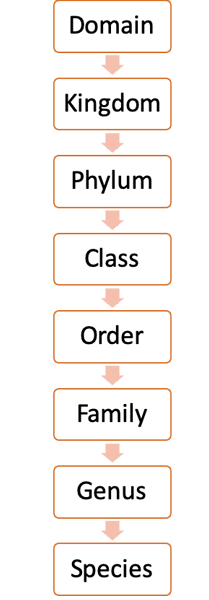

When several genera are much alike, they are now placed together in a group called a family—a term Linnaeus did not use. Several families with general likenesses are placed together in an order. Orders with some broad likeness are placed in a class, and of course each Class, Order, Family, Genus and Species is known by a Latin name.

Luckily for those who do not know Latin, each name for an order ends with the same syllables—iformes (pronounced if-formeez). Each Latin family name ends with idea (pronounced id-ee). So you can tell at a glance that Gauiiformes and Strigiformes and other terms with that ending are names of orders—a very general grouping—while Gauiidae and Strigidae show the closer family relationship. The Latin names for genus and species do not have uniform endings, but the binomial—Linnaeus’s famous two-word label—is always written with the name of the genus first and the name of the species second.

Trinomials

If two or more kinds are only slightly different—not enough for each to be a full species on its own—they are classified together as subspecies. To show the differences, each is now labeled with three words, a trinomial. The first two words of these three are exactly the same as the binomial of whatever one among them was first published with classifying description and label. It may not be the most abundant or best known—it just has to be first in public print. For its trinomial, then, the specific name is repeated. For the others there must be an added third word. For instance, the Canada goose, classified by Linnaeus in 1758, has the trinomial Branta canadensis canadensis to distinguish it from its smaller subspecies, one of which is the cackling goose, Branta canadensis minima, first published in 1885. Since both were seen on the Expedition, both appear with trinomials in the “Summary”. However, it is perfectly proper to list either by the binomial if there is no special need to mark distinction.

Ever Changing Names

The American Ornithologists’ Union has assumed the responsibility for publishing the official data on names of North American birds. The A.O. U. Check-list enrolls each species by Latin binomial and common name, adding information on order, family and genus and details of discovery site and first publication. The surname of the original classifier follows the binomial. If his original label has been changed, his name is in parentheses. There are many such changes—especially transfer to a different genus for scientists know much more about analysis of body structure than they did a generation ago.

The species name, however, is almost always retained, and so it becomes the word to check for identification when you are comparing the 1983 binomials used with those in an older or newer reference. The whistling swan, for instance, has a new common name—tundra swan—and is in a new genus—Cygnus instead of Olor—but it is still species columbianus. No other member of its family (Anatidae: swans, geese, ducks) is allowed to use this name. The ex-whistler is the only columbianus in the group, whatever the new generic label may be.

Changing generic labels is not done just to trade one tongue-twisting Latin word for another. A change only follows assignment to a new genus, for the binomial is always a genus-plus-species combination. Formerly American swans were thought to be in a different genus from Eurasian species, but the new label indicates that they are all in genus Cygnus.

Lewis’s woodpecker has gone through even more changes. When Wilson first labeled it in 1811, all woodpeckers were put in genus Picus, and he added the species name torquatus (ring-necked), unaware that it was already assigned to another woodpecker. Consequently, his label was not valid, and so credit for first publication goes to Gray, who classified it as Picus lewis in 1849. In 1866 Coues decided that it was different enough to be in a new genus of its own and coined the new generic label Asyndesmus (not bonded together) and so Gray’s name was put in parentheses. In 1983 the A.O.U. committee on nomenclature re-examined this species and decided it really belonged in genus Melanerpes, created in 1832 to enroll the red-headed woodpecker, and so the new label is Melanerpes lewis (Gray).

You can trace all other changes in nomenclature in this same way through the entries in The Check-list. You can also find the meaning of the Latin labels in such books as Words for Birds by Edward S. Gruson (Quadrangle 1972). And the more you study this system, the more admiration you will have for Linnaeus’s insistence on brevity, clarity and universal agreement.

A Sidelight

For one little sidelight, you might like to know that Linnaeus was not stiff-necked about the coinage of his terms. He once used the name of an arch rival—a naturalist who refused to adopt the Linnaean system—to label a plant with a very foul odor. Also, he made mistakes. He intended to name the ruby-throated hummingbird with the specific name colibri—the word for hummingbird in the language of the Taina Indians of the Caribbean. Somehow it turned up in print as colubris—Latin for snake! And the error has never been corrected. There it is to this day, a consolation for editors and authors who see similar errors gremlin their way to the printed page.

Perhaps one of the best things about Latin labels is that you can take them or leave them. Skip over them if you please, but when you need them, there they are.

Notes

| ↑1 | Virginia C. Holmgren, “Melanerpes lewis“—Those Latin Words (Binomials or Trinomials). Why Do We Need and Use Them?, We Proceeded On, May 1984, Volume 10, Nos. 2 and 3, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol10no2.pdf#page=26. |

|---|