Captain Bruno Hecata

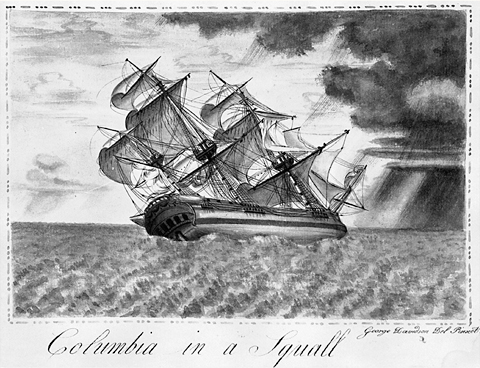

George Davidson, the talented amateur artist who created this dramatic illustration in 1793, was a ship’s painter in the crew of the Columbia on its second fur-trading voyage. With a crew of 31 men and boys—the cabin boy, Samuel Homer, was then about 12 years old—the Columbia set sail from Boston on 1 October 1790, and arrived on the Northwest Coast eight months later.

In the larger view, the Corps of Discovery was just part of a trend. It was but one of a great number of expeditions by land and sea made between 1770 and 1870 across the North American continent. Until 1805 those explorers were all seeking the legendary “Straits of Anian,” the “Great River of the West,” and the “Northwest Passage.”

In 1775 Captain Bruno Heceta of Spain, who had been sent to discourage Russian fur traders from gaining footholds along the northwest coast, observed a large “bay” at about 46 degrees north latitude, but adverse currents prevented him from exploring it and he left, naming the unseen river San Roque. In 1778 Jonathan Carver, who explored the upper Mississippi River as far as today’s Minneapolis, relayed presumably Indian information that the “Great River of the West” was called the “Oregan.” The geography of the Northwest remained but vaguely understood for another fourteen years.

Captain Robert Gray

The Columbia Rediviva of Boston made two voyages to the Northwest Coast while owned by Joseph Barrell & Company, a Boston fur-trading firm. Its mission was to barter manufactured goods for sea otter pelts, which in turn were to be traded at Canton, China, for tea, silk, spices, and porcelain. On its first voyage, which began on 20 September 1787, and ended on 9 August 1790, it earned the distinction of being the first U.S. ship to circumnavigate the globe.[1]On that trip Gray sold nearly 1,000 furs in Canton, China, for $21,404. By 1805 some two hundred thousand skins of otter, seal, and beaver would be sold in China every year.

Under the command of Captain Robert Gray the Columbia left Boston again on 1 October 1790, arriving at Vancouver Island on 3 June 1791, and wintering there. Resuming his pursuit of Indian trade in the spring, on 11 May 1792, Gray took the Columbia over the bar into the estuary of a large river. His entry in his log was terse: “we found this to be a large river of fresh water, up which we steered. Vast numbers of natives came alongside.” Those natives, reported first mate John Boit, “appear’d very civill (not even offering to steal).” In fact, they were open for business. “During our short stay,” Boit added, we collected “150 Otter, 300 Beaver, and twice the number of other land furs.”

For nine days they explored some thirteen miles upstream, and anchored in the bay that still bears Gray’s name—the same place where Lewis and Clark, calling it “Shallow Bay,” were pinned down for two miserable days by rough seas, high tides and relentless winds. Gray and his crew returned to Boston on 26 July 1793, leaving behind only a name—Columbia’s River.

“It seems probable,” writes Stewart Holbrook, “that Captain Gray was more pleased with his success at trading with the natives than with the fact that he had discovered and named a river.”[2]The Columbia (New York: Rinehart, 1956). In fact, he never published his discovery. It remained for the British captain, George Vancouver, who crossed the Columbia Bar a few months after Gray, to announce it in his journal, Voyage of Discovery To The North Pacific Ocean, which was published in 1798. Gray himself quickly sailed into obscurity, dying in 1803, or maybe 1806, or perhaps 1807. No one knows. At least he outlived the Columbia Rediviva which was decommissioned and dismantled in 1801.

Captain George Vancouver

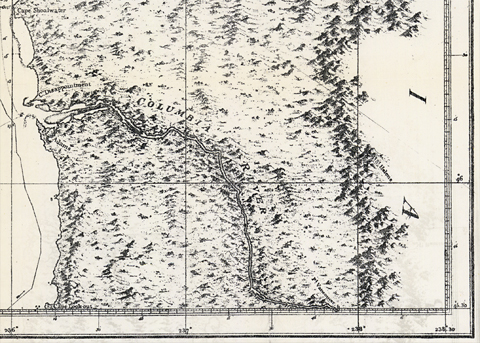

“A chart shewing part of the coast of N.W. America; with the tracks of His Majesty’s sloop Discovery and armed tender Chatham”[3]John Logan Allen, Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (New York: Dover, 1975), pp. 96-97.

Published 1798

To see labels, point to the map.

Washington State University Libraries.

Lewis may have carried a tracing of Vancouver’s map.

Although Captain Gray was prouder of his success as a fur trader than of his exploration and his renaming of the “Great River of the West,” his courageous crossing of the treacherous bar and his exploration of the Columbia’s estuary, together with Lewis and Clark’s four-month sojourn at Fort Clatsop thirteen years later, provided firm bases for the United States’ official claim to sovereignty over all of the territory drained by the great Columbia River below the forty-eighth parallel—”Oregon” country.[4]The origin and meaning of the name “Oregon,” “Ouragan,” or “Oregan,” is open to question. The first known written occurrence of it was in 1765, when the American … Continue reading

On 29 October 1792, after pitching camp at today’s Camas, Washington, opposite the mouth of Sandy River, Lieutenant Broughton and his crew rowed upriver to within an estimated two miles of “a sandy point terminating our view of the river,” which he named for Captain Vancouver.[5]George Vancouver, A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World, 1791-1795 (4 vols., ed. W. Kaye Lamb, London: The Hakluyt Society, 1984), 2:759-760. Lieutenant Broughton also … Continue reading Point Vancouver is believed to be at the bend of the river opposite the lower end of Rooster Rock State Park, where Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery camped on 2 ember 1805. Broughton estimated he was then about 100 miles up the Columbia from its mouth; Point Vancouver today is 128 miles above the center of the channel at the mouth.[6]River Mile Index, Main Stem, Columbia River. Hydrology and Hydraulics Committee, Pacific Northwest River Basins Commission, Revised July 1972. Had Broughton proceeded on another two miles, he could easily have seen Beacon Rock, just fourteen miles farther upstream. In fact, as Master’s Mate John Sherriff reported, Indian informants told them that if they went up a little farther they would “meet with a fall, where were plenty of Salmon.” However, the crew had only two days’ provisions to see them back to their ship, so the next morning they headed back down the river.[7]Andrew David, ed., “John Sherriff on the Columbia, 1792: An Account of William Broughton’s Exploration of the Columbia River,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Vol. 82, No. 2 (April … Continue reading

Clark’s Expectations

Either from the tracing of Vancouver’s map, or from the map of the Northwest drawn especially for the Lewis and Clark Expedition by Nicholas King, which was based partly on Vancouver’s chart, Clark created a map at Fort Mandan in the winter of 1804-1805 that reflected the captains’ understanding of the geography that still lay ahead of them, including as much as was then known and conjectured about the Columbia River.

George Vancouver believed that the prominent peaks he and Broughton saw and named (Mt. Hood, Mt. St. Helens, and Mt. Rainier) were part of the Rocky Mountain range, and William Clark had no reason to think differently at the time he drew this map at Fort Mandan in the winter of 1804-1805. Point Vancouver would be about where the meridian crosses the Columbia at center. Lewis may have had limited advance knowledge of what lay west of Fort Mandan, but once they reached the Columbia, they knew more precisely where they were, and where they were going.

The Columbia Rediviva

Bearing in mind the size of Lewis and Clark’s barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) which was 55 feet long, with a beam of 8 feet, 4 inches, a draft of 3 feet, and a burthen (burden, load) of 12 tons, consider the oceangoing ship Columbia Rediviva, that Robert Gray sailed from Boston, around the horn of South America, and north along the Pacific Coast to the mouth of the Great River of the West, in 1792.

Specifications:

- A full-rigged three-masted ship (foremast, mainmast, mizzenmast [aft of the mainmast])

- Length: 83 feet, 6 inches

- Beam (width), 24 feet, 2 inches

- Draft (depth below waterline), 11 feet

- Burthen (capacity), 213 tons

- Crew, 16-18 minimum; 30-31 maximum

- Built in 1787 (or rebuilt; the word rediviva means “revived”), Plymouth, Massachusetts[8]Frederic W. Howay and others, Voyages of the “Columbia” to the Northwest Coast, 1787-1790 and 1790-1793 (Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press in cooperation with the … Continue reading

- Decommissioned 15 October 1801, and salvaged or, as is written at the end of her register in the National Archives (see footnote), she was “ript to pieces.”

For Comparison:

One of the largest wooden sailing vessels ever built in the U.S. was the Henry B. Hyde, which was the pride of the American Merchant Marine at the time of its launching in 1884.

- Length, 267′ 9″

- Beam—45′

- Draft—28′ 8″

- Crew, 36-40 men

- Burthen, 2462 ton

Notes

| ↑1 | On that trip Gray sold nearly 1,000 furs in Canton, China, for $21,404. By 1805 some two hundred thousand skins of otter, seal, and beaver would be sold in China every year. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Columbia (New York: Rinehart, 1956). |

| ↑3 | John Logan Allen, Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (New York: Dover, 1975), pp. 96-97. |

| ↑4 | The origin and meaning of the name “Oregon,” “Ouragan,” or “Oregan,” is open to question. The first known written occurrence of it was in 1765, when the American soldier and entrepreneur Robert Rogers (1731-1795) petitioned George III of England for permission to mount an expedition that would follow the “Great River Ourigan” to the Pacific Ocean. To that end, Rogers sponsored Jonathan Carver’s expedition. Norman Gelb, ed., Jonathan Carver’s Travels Through America, 1766-1768 (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1993), 20-21, 36-37. |

| ↑5 | George Vancouver, A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World, 1791-1795 (4 vols., ed. W. Kaye Lamb, London: The Hakluyt Society, 1984), 2:759-760. Lieutenant Broughton also named the “remarkable mountain” in view toward the southeast, for Lord Hood, Vice-Admiral of the British Navy. |

| ↑6 | River Mile Index, Main Stem, Columbia River. Hydrology and Hydraulics Committee, Pacific Northwest River Basins Commission, Revised July 1972. |

| ↑7 | Andrew David, ed., “John Sherriff on the Columbia, 1792: An Account of William Broughton’s Exploration of the Columbia River,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Vol. 82, No. 2 (April 1992), 58. |

| ↑8 | Frederic W. Howay and others, Voyages of the “Columbia” to the Northwest Coast, 1787-1790 and 1790-1793 (Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press in cooperation with the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1990, 1941), footnote, page vi. Judge Howay’s conclusion was corroborated prior to the publication of his book, on the authority of two ship’s registers at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., by the state supervisor of the National Archives Project of the Works Progress Administration back in the 1930s and 40s, and by a representative of the Peabody Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. Many students of the river and its exploration have chosen to believe that the famous vessel was built at Hobart’s Landing at Norwell, Massachusetts, in 1773. It is undeniable that there was in fact a ship named Columbia which was built there by private entrepreneurs in that year, but evidently Howay found insufficient evidence to support a declaration that it was the one which was renamed Columbia Rediviva, and which lent its name to the previously anonymous “Great River of the West” in 1787. Indeed, Howay points out: “After having, by the discovery of the Columbia River, laid one of the foundations of her country’s claims to the region ‘where flows the Oregon,’ the movements of the Columbia are uncertain, for it is difficult to identify her among the various ships bearing that name.” It is impossible to contravene certain disagreements when it comes to historical details that are inherently irreconcilable. Ironically, a similar and perhaps equally contentious argument prevails concerning the place where the barge—more commonly but incorrectly dubbed a “keelboat”—of Lewis and Clark was built in 1803. And overriding all others, there remains the still perennial debate over the cause of Meriwether Lewis‘s death. (See historian Clay Jenkinson’s analysis of the evidence, and his answer to the question, “Suicide or Murder?” which is the conclusion of his authoritative essay, The Last Journey of Meriwether Lewis. |