On 18 October 1805, the expedition’s canoes finally head down the Columbia River. The best paddlers steer through The Dalles and Cascades of the Columbia without incident, and they all continue downriver passing numerous Lower Chinookan villages. After three weeks hunkering down in dismal nitches and bays at the river’s mouth, they cross to the southern shore and encamp at Tongue Point while Lewis searches for a place to spend the winter.

After trading for horses with Sacagawea’s people, the expedition turned north and then west, on what would indisputably be the most exhausting and debilitating segment of the entire journey, the passage across the Bitterroot Mountains.

Columbia River Basalts

by John W. Jengo

The region of the lower Snake River and the Columbia River’s course through the Columbia Plateau and Gorge experienced volcanic activity starting some 55 million years ago, although the expedition would primarily encounter rock units of Miocene-age.

In the afternoon of 16 October 1805, the expedition portaged around “the last bad rapid as the Indians Sign to us”–the last on the Snake River, that is–and soon arrived at the “Great River of the West,” the Columbia.

They encountered several rapids that nineteenth of October, including “a verry bad one” about two miles long. Clark climbed a 200-foot “clift” from which he could see many miles across the high desert.

Hat Rock

The enlisted men must have recognized it at a glance, this pile of columnar basalt all together resembling a well-weathered gentleman’s hat with a work-worn brim. Two centuries later, it would be one of the few Lewis and Clark landmarks left above Columbia River.

This scene’s most arresting feature is still the “high mountain of emence hight covered with Snow” on the photo’s horizon. Clark mistook it for Mount St. Helens. The Indians called the mountain Pahtoe. Since 1838 it has been known as Mount Adams.

The Deschutes River

by Barbara Fifer

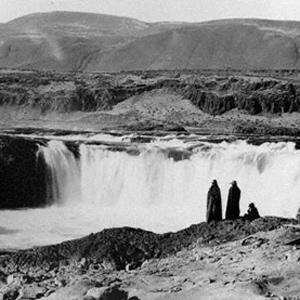

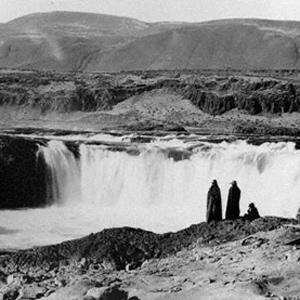

The fall salmon run was ending when the Corps arrived at the Great Falls of the Columbia, several miles below the mouth of Towarnehiooks, with some native people still at the river, fishing with gigs and nets and processing their salmon harvest.

October 21, 1805

Columbia River rapids

Near John Day Dam, WA The paddlers navigate several rapids while the non-swimmers walk around them, something Clark says has become routine. They buy food and firewood from Indians who show “great kindness,” and Collins shares his home-brewed beer.

The 21 October 1805 rock fall geologic notation is likely referring to mass-wasting features along a fourteen-mile long stretch of dramatically steep slopes visible today between Blalock Canyon and the John Day River.

Near the west end of the island, they passed a sizeable tributary local Indians called To war ne hi ooks. The journalists left us no hint that the word they heard as Towarnehiooks was a Chinookan expression meaning “enemies.”

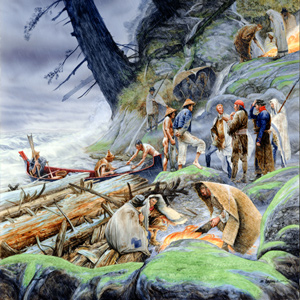

The Corps of Discovery reached a many-faceted barrier, Celilo Falls, which required a portage. The falls proved to be the beginning of fifty-some river miles that also held The Short and Long Narrows (jointly called The Dalles), and ended with the lengthy Cascades of the Columbia.

Geology of The Dalles

by John W. Jengo

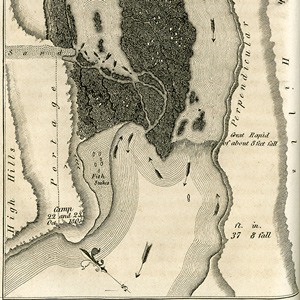

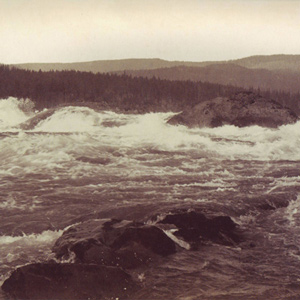

Over four days (22-25 October 1805) the expedition would be navigating through one of the most exciting and difficult stretches of the entire water route to the Pacific. Several outstanding geological features were noted.

During the portage around the Falls of the Columbia River, as Biddle paraphrased it, “we found that the Indians had camped there not long since, and had left behind them multitudes of fleas.”

October 23, 1805

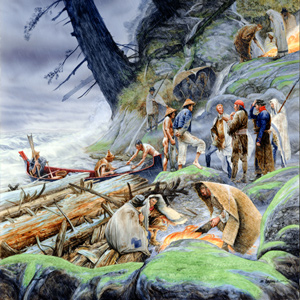

Lining Horseshoe Bend

Celilo Falls, WA-OR While the men are lining the Horseshoe Bend of Celilo Falls, Lewis buys a Chinook canoe trading the smallest dugout, a hatchet, and a few trinkets.

Here the Columbia was “an agitated gut Swelling, boiling & whirling in every direction.” Even so, Cruzatte and Clark agreed that they could run the canoes through.

The party “Came too, under a high point of rocks on the Lard. Side below a creek”—Quenett (“salmon”), now Mill Creek—a “Situation well Calculated to defend our Selves,” and duly named their bivouac “Fort Rock Camp.”

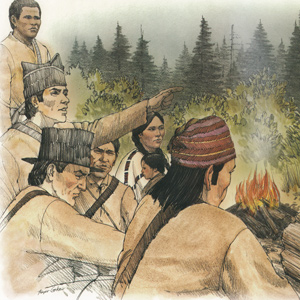

There really was no need for him to have been on the defensive. Pierre Cruzatte cast a spell over the assembled Indians with his fiddle, which was much more effective than any pompous diplomatic talk.

The consolidated rocks that compose the Gorge were formed by a complex interplay of Columbia River Basalt Group flood basalt deposition and basin subsidence, along with contemporaneous folding and faulting—not the Glacial Lake Missoula floods.

Columbia Gorge Waterfalls

by John W. Jengo

William Clark: “Saw 4 Cascades caused by Small Streams falling from the mountains on the Lard. Side.”

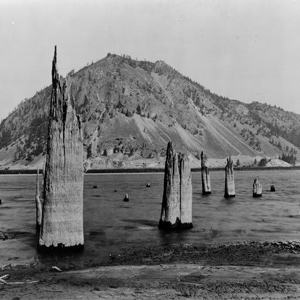

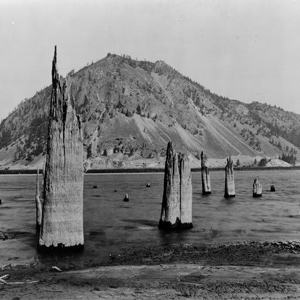

A Submerged Forest

by John W. Jengo

On 30 October 1805, Clark documented the presence of a submerged forest, which along with the burning bluffs of northeastern Nebraska, the “Burnt Hills” of North Dakota, and White Cliffs of the Missouri in central Montana, remain one of the expedition’s most famous geological observations.

![]()

“a remarkable high detached rock Stands in a bottom on the Stard [starboard, the navigator’s right] Side & about 800 feet high and 400 paces around”

Clark described the Cascades as having a “Great Shute” where the Columbia dropped about twenty feet over both large and small rocks, “water passing with great velocity forming & boiling in a most horriable manner.”

The Bonneville Dam, completed in 1938, raised the level of this part of the Columbia seventy-two feet and permanently obliterated the place Lewis and Clark called the “Great Shute.”

Bonneville Dam, was the first dam to be built on the Columbia River. The slackwater pool it impounds, called Lake Bonneville, eliminated the Cascades as a barrier to commercial shipping, and provided a deep, navigable channel for barges and tugs.

Rooster Rock at Crown Point

by John W. Jengo

The promontory of Crown Point comes to mind when Clark mentions in his notebook journal that the expedition camped “under a high projecting rock.”

Phoca (Seal) Rock

by John W. Jengo

The mid-river island identified as “Phoca” and “Seal rock” on one of William Clark’s route maps is a compact landslide block that detached from the Cape Horn headland.

The expedition traveled out from under an ancient river channel frozen in time to a river discharging huge volumes of sediment in real time, the “quicksand river,” now known as the Sandy River.

On the night of 4 November 1805 the expedition camped near a pond now called Post Office Lake. The next morning a weary, groggy Clark complained that he “could not Sleep for the noise” made by the numerous waterfowl.

November 5, 1805

River crowded with Indians

Near Prescott, OR After a night made sleepless by noisy waterfowl, the expedition heads down the Columbia. They pass the large village known today as Cathlapotle and encounter various Indians. In eastern Colorado, a Spanish force trying to stop the expedition is attacked.

Cascade Mountains at Dawn

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In 1838, a patriotic citizen started a campaign to change the Cascade Mountains into the “Presidential Range.” This was to include renaming Mount Hood after John Adams.

When the sky cleared briefly at about noon on 7 November 1805, a rising cheer may have startled the myriad waterfowl in the area, for Clark wrote, “we are in view of the opening of the Ocian, which Creates great joy.”

They fancied they could already see and hear the Pacific Ocean, although it was still more than 20 miles away, well beyond their horizon. Clark’s famous exclamation was another instance of the captains’ habit of reacting prematurely.

On the morning of 8 November 1805, the Corps’ flotilla entered a “nitch” they called Shallow Bay and paused for their midday meal near the remains of an Indian village with “great numbers of flees which [we] treated with the greatest caution and distance.”

November 11, 1805

Kathlamet visitors

Small Nitch near Knappton, WA The Corps makes the best of their poor location exposed to high waves and driving rain. Five Kathlamet visitors skillfully cross the river in a canoe loaded with sockeye salmon.

It was “the most disagreeable time I have experienced,” Clark grumbled on 15 November 1805. “Confined on a tempiest Coast wet, where I can neither get out to hunt, return to a better Situation, or proceed on”

“…this I could plainly See would be the extent of our journey by water, as the waves were too high at any Stage for our Canoes to proceed any further down ….”

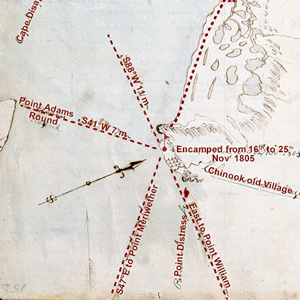

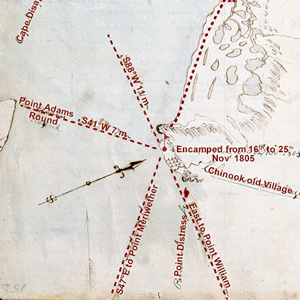

The morning of 16 November 1805 dawned “Clear and butifull.” At noon Clark took advantage of the conditions and made an observation of the sun’s altitude for latitude. He used the sextant and artificial horizon.

Private Whitehouse thought his captains had named Cape Disappointment “on account of not finding Vessells there,” but it had received the name years earlier.

Clark was pleased that his men appeared “much Satisfied with their trip beholding with estonishment the high waves dashing against the rocks & this emence ocean.”

November 20, 1805

Sacagawea's belt of blue beads

Station Camp near Chinook, WA Clark’s party returns to Station Camp where they meet with Chiefs Concomly and Shelathwell. Another Indian trades two sea otter skins for Sacagawea’s belt of blue beads, and she is given a new coat.

November 24, 1805

The winter camp decision

Station Camp near Chinook, WA Before deciding where to winter over, Clark recording the opinions of each member including York and Sacagawea. Clark lists the advantages of the southern shore.

As the Corps rounded Tongue Point the wind rose hard from the west, and heavy seas with torrential rain forced them back to the east shore of the narrow isthmus, where they huddled for ten miserable days.

At The Dalles in 1902, a hospitable local citizen helped Wheeler make his way to the brink of the long narrow channel and chasm through which Lewis and Clark took their canoes, where he “overlooked the swirling waters as they boiled and raged.”