Alexander Mackenzie was the first literate traveler to cross the North American continent north of Mexico. In several ways, Lewis emulated him.

From Canada, by Land

It’s been 200 years since a bold young Scotsman wrote the headline for his own triumph of exploration: “Alexander Mackenzie, from Canada, by land, the twenty-second of July, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-three.” Mackenzie stroked his graffiti “in large characters,” he recalled, on the rocky bank of a Pacific Ocean fjord he had reached the day before. He was the first literate traveler to cross the North American continent north of Mexico, beating Meriwether Lewis and William Clark by nearly 12 years.

Those observing the 1993 bicentennial of Mackenzie’s journey from the Canadian interior can cite important differences from the later, more elaborate Lewis and Clark traverse. Mackenzie at heart was a businessman, an important partner in a private fur-trading company based in Montreal. He led a party of just nine other men on a 2,800-mile round-trip dash lasting less than a year. Lewis and Clark were Army officers executing a U.S. government mission planned by the President and paid for by Congress. They led 31 soldiers and civilians on a trip covering more than twice as much ground and lasting two and a half years.

Yet there were striking similarities. Both exploring parties traveled most of the way on rivers. Both came to river junctions requiring an agonizing decision: which way to go? Most of the men pointed one way, but the leaders chose the opposite. Both parties relied on help from native people met en route. Both pioneered paths across the Rocky Mountains that never became useful highways for later travelers, so it’s been said that both expeditions failed to meet their own objectives. In compensation, though, both trips generated priceless journals of wilderness travel that thrilled stay-at-home readers with an early inkling of the wonders of the far West.

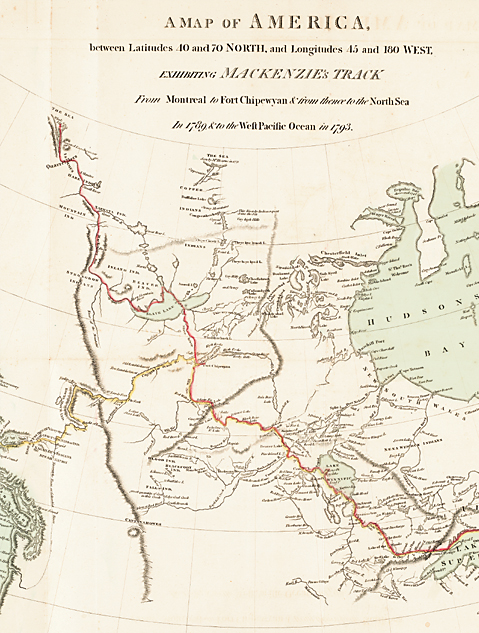

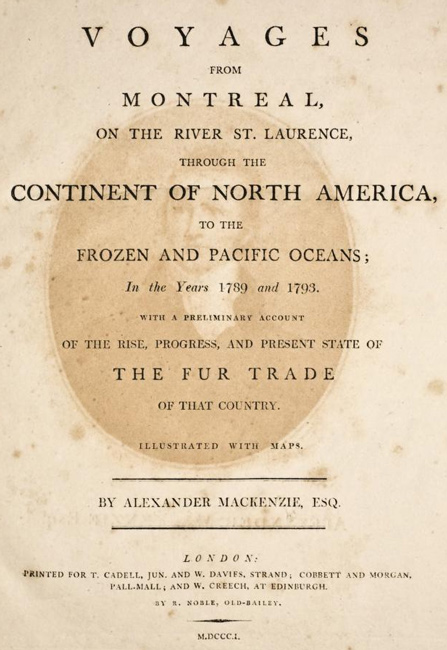

Mackenzie’s journal was published in London eight years after his Pacific trip.[2]Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages from Montreal (T. Cadell, London, 1801; reprint, Charles E. Tuttle Co., Rutland, 1971). A conveniently annotated edition of the complete text of Mackenzie’s Pacific … Continue reading The Scottish-born explorer told first of a 1789 canoe voyage from Fort Chipewyan, a North West Company trading post on Lake Athabaska high up in modern Alberta. He was looking for a western route to the Pacific, but the big river he followed (it now bears Mackenzie’s name) carried him north to the Arctic Ocean instead. Mackenzie then went to London to learn navigation, and returned through Montreal to Fort Chipewyan in 1792. Still looking for a way to transport furs to the Pacific, he took a canoe 500 miles southwest-ward up the Peace River to a spot where his party holed up for a winter so cold that ax blades “became almost as brittle as glass.” He resumed the journey up the Peace in May 1793. Upon reaching the Pacific coast in July of that year, he returned to Fort Chipewyan the same way after an absence of 11 months.

Voyages from Montreal

Mackenzie’s 1801 book, Voyages from Montreal (written with the help of an English ghostwriter named William Combe) recited these adventures in exciting detail.[3]Sir Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages From Montreal to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans, in the Years 1789 and 1793. (London: R. Noble, 1801). It had a major political purpose as well. The businessman-adventurer closed his story by urging British ministers to establish government-protected ports in the Pacific Northwest for shipment of furs to China.

King George III in 1802 knighted Mackenzie for his exploring feats. The king’s ministers, however, stonewalled any notion of costly subsidies for Canada’s fur business. In America, President Thomas Jefferson had no way of foretelling the British government’s indifference when he read Mackenzie’s book in the summer of 1802. The President saw Mackenzie’s plan as a challenge that could be met by establishing a more southerly trade route along the Columbia and Missouri Rivers, which he thought nearly interconnected at a single ridge of the Rockies. In January 1803, he asked Congress to finance a small expedition to explore that route.[4]Jefferson’s message to Congress, 18 January 1803, in Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Related Documents, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), … Continue reading

If Mackenzie’s book triggered the Lewis and Clark expedition, it also appeared to guide some of the American logistical planning. Mackenzie’s party numbered 10 men, so Jefferson told Congress an intelligent officer with 10 or 12 chosen men should be enough. Only later did Lewis and Clark decide to triple their party’s size. Noting that Mackenzie smashed his single thermometer early in his trip, Jefferson’s men took three as insurance, but all were likewise broken on their outbound journey; thereafter the Americans, like Mackenzie, had to guess at the temperatures of the West. The Scot said coastal natives prized beads as currency; Lewis and Clark took a big supply, but not enough blue ones as it turned out. Mackenzie took a dog; so did Lewis.

Several historians have suggested that Lewis and Clark carried Mackenzie’s book with them to the Pacific for en-route reading. Bernard DeVoto said so flatly in a 1955 essay, without offering evidence.[5]Bernard DeVoto, “An Inference Regarding the Expedition of Lewis and Clark,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 99, No. 4 (30 August 1955), 189. Donald Jackson was more cautious in his 1959 inventory of books in the baggage of the American explorers.[6]Donald Jackson, “Some Books Carried by Lewis and Clark,” Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, Vol. 16, No. 1 (October 1959), 4, 10-11. Mackenzie’s book might go on the list “by inference,” he said, because the captains’ journals “reveal a familiarity with the ideas of Mackenzie and a knowledge of his cartography.” Jackson noted that another of the names Lewis and Clark applied to the Columbia River was “Tacoutche Tesse,” which was also Mackenzie’s name for it. (Mackenzie was wrong: what he thought was the Columbia was really the Fraser River.)

Literary Echoes

The idea that the Americans consulted Mackenzie’s account along the way is reinforced by some literary echoes found in the Lewis and Clark journals:

- Mackenzie’s memorable notice that he had arrived at the Pacific “by land” from Canada probably inspired Clark’s own inscription on a big tree near the western end of his journey. The captain said he “engraved my name & by land the day of the month and year, as also Several of the men.”[7]Mackenzie’s account of his inscription in Sheppe, First Man West, p. 239. Clark’s tree carving on 18 November 1805, is in Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark … Continue reading

- The Scottish explorer made a lyrical entry just eight days westward of his wintering post on the Peace River: “At two in the afternoon the Rocky Mountains appeared in sight, with their summits covered with snow, bearing South-West by South. They formed a very agreeable object to every person in the canoe.” Lewis knew it was an important milestone when on 26 May 1805, he “beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time,” so he fancied up his prose a notch to mark the occasion: “these points of the Rocky Mountains were covered with snow and then the sun shone on it in such manner as to give me the most plain and satisfactory view.”[8]Sheppe, First Man West, p. 88; Moulton, Journals, 4:201.

- Lewis gushed optimism as his expedition left Fort Mandan in North Dakota for the Pacific on 7 April 1805. This trip, he wrote, “had formed a darling project of mine for the last ten years.” A curious expression, “darling project,” but it could have been picked up from Mackenzie’s lament on the Fraser River that “my darling project would end in disappointment” if no native guides were found.[9]Moulton, Journals, 4:10; Sheppe, First Man West, p. 174.

Mackenzie ultimately enticed a come-and-go series of local people to show him the way west from the Fraser River, where he abandoned his canoe, to Canada’s indented coastline. Not for him was the Lewis and Clark luxury of buying Indian horses for this two-week, 218-mile trek over mountains streaked yellow and red by vulcanism. There seemed to be no horses at all in that country, so Mackenzie and his eastern voyageurs had to walk like everybody else.

The journals of both expeditions dwelt on the ups and downs of relations with Indians, due more to like circumstances than to any literary copying. Both parties depended on the neighborhood people for food and direction. Like the later Americans, Mackenzie tried to cultivate good relations by acting as a wilderness doctor for various native ailments. Like them, he awed the locals with simple displays of European technology. The use of a magnifying glass to make fire from sunbeams so astounded some coastal Indians, he reported, “that they exchanged the best of their otter skins for it.” More than once, on meeting families of wary natives, Mackenzie melted the adults’ reserve by handing out sugar to the kids. His long descriptions of the appearance and manners of Cree, Tsattine, Sekani, Kluskus, Bella Coola and Bella Bella people anticipated the even more detailed ethnography of Lewis and Clark.

Indian Relations

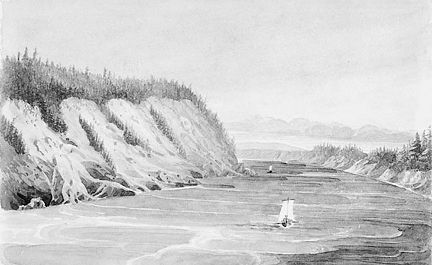

Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabaska

(“Lake of the Hills” on Mackenzie’s map), in 1820

by George Back (1796-1828)

Acquired by the National Archives of Canada with the assistance of Hoechst and Celanese Canada and with a grant from the Department of Canadian Heritage under the Cultural Property Export and Import Act, C-145926.

But in his patient dealings with western Indians, as with underlings in his own party, Mackenzie was making an effort. The Scotsman may have been a brilliant wilderness leader, judged Bernard DeVoto, “but he is a hard man to like.”[10]Bernard DeVoto, The Course of Empire (1952, Norwalk: Easton Press, 1988), p. 309. Biographer James Smith, in a book provocatively titled Alexander Mackenzie, Explorer: The Hero Who Failed, saw “more than a touch of pride and arrogance” in his subject.[11]James K. Smith, Alexander Mackenzie, Explorer: The Hero Who Failed (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd., 1973), p. 1. Maybe that attitude explains Mackenzie’s sparing use of names in his journal, both of the faceless individuals he traveled with and the natives he met.[12]Only once in his journal did Mackenzie give a roster of his party, naming 8 of the 9 men. Sheppe, First Man West, p. 79. Mackenzie never again referred to most of his voyageurs by name, and one of … Continue reading The more forthcoming Americans made their journals as rich as Russian novels with the names—in careful phonetic renderings—of nearly every Indian in sight, including some who gave them a hard time.

Mackenzie never gave names to people who guided him, and he bothered to put down the name of just one coastal village chief—Soocomlick—who particularly befriended the party. At his graffiti rock on the Dean Channel, Mackenzie felt himself harassed by a never-named “troublesome fellow” who kept complaining that Europeans had recently fired guns at members of his Bella Bella tribe. The troublesome fellow identified his white persecutors as “Macubah” and “Bensins,” as Mackenzie recalled. Not until the trader returned to Britain did he learn he had nearly been involved in a chance exploratory traffic jam. Just seven weeks before Mackenzie’s arrival in the Dean Channel, Captain George Vancouver had sailed into that same spot on his 1792-1794 survey of the Northern Pacific coastline. Some historians have suggested Vancouver himself was the trigger-happy “Macubah” of Mackenzie’s story, while “Bensins” may have been the survey’s naturalist, Archibald Menzies.[13]Sheppe, in a note on p. 235 of First Man West, ventured that Vancouver and Menzies “apparently” were the seamen that the Bella Bellas complained about. In his Vol. 1 introduction to … Continue reading

White travelers—Lewis and Clark among them—commonly referred to the natives they met as “savages.” Even for his time, however, Mackenzie went out of his way to assert an explicit doctrine of white racial dominance. In a revealing incident on the Fraser River, a tribesman broke into Mackenzie’s interrogation about the land ahead. If white men already know everything, said the uppity Indian, why do you have to ask the way? The explorer replied that he knew about the whole world, including the location of the ocean he was trying to reach, but only needed information from you backwoods rubes about petty local obstacles. Mackenzie wanted his readers to understand that he had scored a heavy point on the Indians in this exchange: “Thus I fortunately preserved the impression in their minds, of the superiority of white people over themselves.”[14]Sheppe, First Man West, p. 166.

Lewis and Clark never expressed that attitude so bluntly, though they may have shared it. Nevertheless, Mackenzie got most of what he wanted from the natives without any fighting or killing. On his trip not one man died, either in his own party or among the people he met.

Celestial Observations

Jefferson needed no prompting from anyone’s journal on the need for his explorers to take good measurements of latitude and longitude across the continent, but he must been impressed by Mackenzie’s diligence in the task. The Scot recorded 34 latitudes on his round trip from Fort Chipewyan to the Pacific, obtained by measuring the sun’s noon altitude with his sextant. Special perseverance was required when Indians flocked around to watch the white wizard perform this mysterious rite; on one occasion some coastal residents anxiously told Mackenzie to put his sextant away, lest it scare away the salmon on which their lives depended.

The latitude readings helped Mackenzie realize how far south he drifted while aiming west. The graffiti rock on the Dean Channel stands more than 6 degrees of latitude southward of his Fort Chipew-yan starting point, about equal to the north-south distance between Chicago and Nashville.

With similar diligence on their longer trip Lewis and Clark computed just over 80 latitudes in the field. The Americans stumbled, however, by shunning Mackenzie’s method of getting relatively accurate longitudes. On his London visit in early 1792 Mackenzie bought a telescope big enough to pick out the four brightest moons of the planet Jupiter. He also got a British Nautical Almanac predicting the Greenwich times these moons would disappear behind the planet. By comparing his local time of seeing these eclipses with the Almanac times, the explorer could figure his longitude west of Greenwich at the rate of 15 degrees for each hour of time difference.

Mackenzie had to lug the telescope on his own back during the final march over the mountains from the Fraser River to the saltwater inlet at the modern village of Bella Coola, British Columbia. When he set up the instrument in the fjord near his graffiti rock, Mackenzie got a rare cloudless shot at Jupiter and a fairly good longitude of 128°02′ W. That was by far the most important of the six longitudes obtained from Jupiter during his round trip.

Peace River Decision

Jefferson read Mackenzie’s account of that method’s success and it’s puzzling why the President didn’t tell Lewis to use Jupiter too. Perhaps he feared a telescope might be too easily broken on a long trip, but the American choice of a trickier way of getting longitude didn’t pay off. Lewis used a sextant to measure angles between the moon and nine bright stars, or the sun, as a way of knowing Greenwich time with the help of the Nautical Almanac. On the expedition he and Clark took 60 such “lunar distance” measurements, but postponed the tough calculations needed to produce actual longitudes in the field. Mackenzie took three lunar distance angles himself, also without recording a computed answer. Evidently he found that Jupiter gave easier results.

Astronomy aside, both parties carefully recorded “courses and distance,” or miles traveled on each compass heading, to mark their progress by dead reckoning. At the outset neither group knew much about pioneering through world-class mountains like the Rockies. Mountain geography was a difficult learning process for these explorers, but they got pretty good at it.

In May 1793, Mackenzie left the plains and wrestled his single canoe upstream through a deep canyon where the Peace River flows from the Rockies. Still moving west, he came to a place in modern British Columbia between two mountain chains where the Peace forms itself from tributaries coming from the north and south. Mackenzie wrote he would have taken the northern branch, “if I had been governed by own judgment.” Likewise, his Canadian voyageurs looked with professional eyes at the angry current of the Parsnip River coming from the south, and agreed that the gentler Finlay was the way to go. But to the horror of his men, Mackenzie ordered the canoe southward up the Parsnip. As a result, he reported, “we were the greatest part of the afternoon in getting two or three miles.”

Mackenzie took that unpromising turn because he had been coached in advance by “an old man”—unnamed, of course—met earlier on the trip. The Indian warned Mackenzie that when he reached the forks of the Peace, he was “not on any account” to go north. The southern branch, said his coach, would take him to a portage leading to a big new river the explorers were looking for. (Twelve years later Lewis and Clark faced a similar decision when their eight-boat flotilla arrived at a branching of the Missouri River in modern Montana. They had received no prior Indian advice. The men said go north up the Marias River, but the captains studied the waters and correctly picked the southern branch as the main Missouri.)

Crossing the Divide

For 11 more days Mackenzie struggled south-eastward against the Parsnip’s current. The hungry paddlers boiled—what else?—wild parsnips with a long, deep V-shaped canyon with timbered sides scoured by avalanche chutes. On the morning of 12 June the explorers pushed to the end of a narrow lake nearly choked with driftwood fallen from the hillsides. Here, Mackenzie showed that remarkable ability to decipher the direction of watersheds within wildly tumbled terrain, a sense shared with other early travelers of the West. He was at the Continental Divide, and he knew it.

The waters of the driftwood-choked lake have as their ultimate destination the Arctic Ocean, via the Parsnip, Peace, Slave and Mackenzie rivers. That’s why this lake’s modern name is Arctic Lake, and there Mackenzie unloaded his canoe and portaged over “a beaten path leading over a low ridge of land of 817 paces to another small lake.” This span of about seven football fields was labeled “Height of Land” on Mackenzie’s 1801 map of his route, the classic name for a division of waters, though the elevation above sea level is only 2,500 feet. The portage ended at a smaller lake with a current at last flowing Mackenzie’s way. After another short portage there was yet another narrow body of water, now appropriately named Pacific Lake, because it flows to that ocean by way of the McGregor and Fraser rivers.

Lewis could also read drainage divides. Lemhi Pass sits on the modern Idaho-Montana border in a jumble of ridges. Approaching the pass from the east on 12 August 1805, Lewis drank at a spring he knew would reach the Gulf of Mexico via the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. “We proceeded on to the top of the dividing ridge,” he said, and on the opposite side soon “tasted the water of the great Columbia river.” Heading back home through west-central Montana on 7 July 1806, Lewis climbed on horseback a partly wooded slope to arrive at what he identified at first sight as “the dividing ridge between the waters of the Columbia and Missouri rivers.”

That’s the pass (now named Lewis and Clark Pass) which Lewis later told Jefferson was the linchpin of “the most practicable rout which dose exist across the continent” by way of the Missouri and Columbia.[15]Lewis to Jefferson, 23 September 1806, in Jackson, Letters, I:320. The captain, alas, was a better reader of drainages than a prophet of transportation routes. No highway or railroad has ever crossed Lewis and Clark pass; the lonely saddle barely shows a jeep track.

Similarly, the three turquoise-colored lakes in the remote valley enclosing Mackenzie’s Arctic-Pacific divide are today just scenic backwaters, hardly throbbing with commerce. As his trip to the Pacific unfolded Mackenzie knew his route was no good. Murderous rapids in Pacific Lake’s outlet creek nearly ended his mission right there. When he finally reached the Fraser for a downstream cruise to the ocean he discovered a “violent” river threatening death at every bend. His decision to abandon the river and march directly westward won his nominal goal of reaching the sea, but that overland route offended the paddle-and-portage tradition of Canada’s fur culture.

Heroic though it was, Mackenzie’s journey produced no commercial return for the £1,500 it had cost the North West Company. He had reached the Pacific, but he knew that his route could not be used for trade, observed Walter Sheppe, a modern editor of Mackenzie’s journal.[16]Sheppe, First Man West, p. 281.

Mackenzie’s post-expedition career partly paralleled the experiences of Lewis and Clark. Like Lewis, the earlier conqueror of the Rockies suffered a bad case of writer’s block in trying to compose a quick account of his trip. Like Clark, Mackenzie lived long after the big adventure, but neither of them ever went back West to re-experience its exhilarating rigors. “I think it unpardonable in any man to remain in this country who can afford to leave it,” said Mackenzie in a post-expedition letter.[17]Ibid. Mackenzie left Fort Chipewyan and the Canadian north for good in 1794, and thereafter busied himself in fur trade matters at more comfortable stations in Montreal and London. He ultimately returned to Scotland where he died on 11 March 1820, at age 56.

Failures

The notion that both expeditions were failures is true only in the sense that they couldn’t find an easy water route across the continent. They couldn’t find it because it wasn’t there, and the discovery of what’s there—and what isn’t—is the definition of exploring success, not failure. That’s why their negative findings were themselves valuable additions to the buildup of geographic knowledge about the West. The incremental nature of that buildup can be traced in the succession of maps produced as each page of discovery was turned. Vancouver’s naval survey map of the Pacific Northwest was published in 1798, allowing Mackenzie to incorporate that coastline in his 1801 map of his route through the Rockies. These cumulative Vancouver-Mackenzie features, in turn, were used by American cartographer Nicholas King in his summary 1803 map given to Lewis and Clark at the outset of their trip. Clark’s 1814 map relied on these previous benchmarks, while adding enormously to everyone’s grasp of how the wide ranges of the Rockies are situated in the continent’s interior.

Mackenzie’s word pictures were as important as his map pictures. The Scot began his 1801 book with a disclaimer about his descriptive powers: “I am not a candidate for literary fame.” After that, some readers might have been surprised by the author’s detailed attention to the landscape and its animals and plants. After seeing tracks of “large bears,” Mackenzie reported: “The Indians entertain great apprehension of this kind of bear, which is called the grisly bear, and they never ventured to attack it but in a party of at least three or four.” In the murderous Peace River Canyon, he took time to name 12 kinds of local trees; “the shrubs are the gooseberry, the currant and several kinds of briars.”[18]Sheppe, First Man West, p. 281. Mackenzie described grizzly bears on pp. 85, 89; the botanical descriptions at Peace River Canyon are on p. 101.

As geopolitical propaganda Mackenzie’s book failed to entice the British government toward a Northwest Pacific empire. Yet its dramatic portrait of the West—”the rude and wild magnificence of the scenery around”—made it a bestseller among ordinary readers in Europe. Similarly, Lewis and Clark returned to St. Louis in 1806 with first-hand news worth taking to the bank: the West is alive with beaver. Never mind the political dreams of globe-twirling statesmen in Washington, fur business entrepreneurs scrambled west the very next year to cash in.

Spanish explorers to the south had long before started weaving a skein of trails through the North American interior, to which Mackenzie and Lewis and Clark added their northerly contributions. If the feelers sometimes seemed to lead nowhere, the cumulative new layers of geographic insight told later travelers exactly how to go somewhere.

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “Mackenzie’s Wonderful Trail to Nowhere,” We Proceeded On, Volume 19, No. 4 (November 1993), the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original printed format is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol19no4.pdf#page=4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages from Montreal (T. Cadell, London, 1801; reprint, Charles E. Tuttle Co., Rutland, 1971). A conveniently annotated edition of the complete text of Mackenzie’s Pacific journal alone, with maps, is Walter Sheppe, ed., First Man West: Alexander Mackenzie’s Account of His Expedition Across North America to the Pacific in 1793 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1962). Citations in this article are from Sheppe. |

| ↑3 | Sir Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages From Montreal to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans, in the Years 1789 and 1793. (London: R. Noble, 1801). |

| ↑4 | Jefferson’s message to Congress, 18 January 1803, in Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Related Documents, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:10-13. |

| ↑5 | Bernard DeVoto, “An Inference Regarding the Expedition of Lewis and Clark,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 99, No. 4 (30 August 1955), 189. |

| ↑6 | Donald Jackson, “Some Books Carried by Lewis and Clark,” Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, Vol. 16, No. 1 (October 1959), 4, 10-11. |

| ↑7 | Mackenzie’s account of his inscription in Sheppe, First Man West, p. 239. Clark’s tree carving on 18 November 1805, is in Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. (13 vols., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 6:66. |

| ↑8 | Sheppe, First Man West, p. 88; Moulton, Journals, 4:201. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, Journals, 4:10; Sheppe, First Man West, p. 174. |

| ↑10 | Bernard DeVoto, The Course of Empire (1952, Norwalk: Easton Press, 1988), p. 309. |

| ↑11 | James K. Smith, Alexander Mackenzie, Explorer: The Hero Who Failed (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd., 1973), p. 1. |

| ↑12 | Only once in his journal did Mackenzie give a roster of his party, naming 8 of the 9 men. Sheppe, First Man West, p. 79. Mackenzie never again referred to most of his voyageurs by name, and one of the two Indian hunters went entirely nameless through the whole trip. However, the leader frequently mentioned his second-in-command, Alexander Mackay, who later in his career joined John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company. Mackay was killed in the 1811 Indian attack on Astor’s ship Tonquin at Nootka Sound. |

| ↑13 | Sheppe, in a note on p. 235 of First Man West, ventured that Vancouver and Menzies “apparently” were the seamen that the Bella Bellas complained about. In his Vol. 1 introduction to Vancouver’s A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World (1798; London: The Hakluyt Society, 1984), editor W. Kaye Lamb on p. 137 said “Macubah would seem to be unmistakably a reference to Vancouver.” However, Lamb observed that naturalist Menzies couldn’t have been “Bensins” because he wasn’t with Vancouver’s party on 4 June 1793. Vancouver himself reported no trouble with Indians on that stop. |

| ↑14 | Sheppe, First Man West, p. 166. |

| ↑15 | Lewis to Jefferson, 23 September 1806, in Jackson, Letters, I:320. |

| ↑16 | Sheppe, First Man West, p. 281. |

| ↑17 | Ibid. |

| ↑18 | Sheppe, First Man West, p. 281. Mackenzie described grizzly bears on pp. 85, 89; the botanical descriptions at Peace River Canyon are on p. 101. |