“. . . the succession of curious adventure wore the impression on my mind of inchantment; at sometimes for a moment I thought it might be a dream.”

Prairie Rattlesnake, Crotalus viridis viridis

Photo by John Jengo. © 2021 by Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation.

The Prairie Rattlesnake’s Crotalus—”Little Bell”

Listen to the warning:

Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics, Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. All rights reserved.

The members of the Corps of Discovery must have hoped to hear a rattlesnake’s warning in time to avoid the strike.

It had been a long, exhausting day, filled with a succession of curious adventures, any one of which might have turned into misfortune instead of enchantment. Meriwether Lewis returned to the camp after dark that night, “much fortiegued, but eat a hearty supper and took a good night’s rest.” The next morning he awoke to find “a large rattlesnake coiled on the leaning trunk of a tree under the shade of which I had been lying at the distance of about ten feet.”

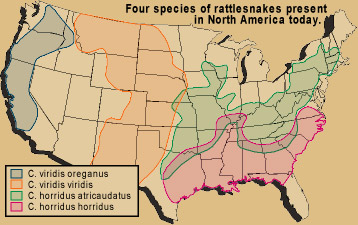

It certainly wasn’t the first rattlesnake seen on the trip, but he killed this one, and took time to study it. “They do not differ in colours,” he observed, “from the rattlesnakes common to the middle Atlantic states, but considerably in the form and figures of those colours.” Actually, he had found a new species, later designated viridis viridis, of the genus Crotalus. Crotalus is Greek for “little bell,” referring to the rattly bell with which this reptile warns creatures it deems threatening. The species name, viridis, a form of the Latin word for “green,” refers to the greenish-gray tinge around the dark brown markings on the snake’s back. The common name for Crotalus viridis viridis is prairie rattlesnake. The similar reptile he had seen back home in the middle Atlantic states could have been one of three species of the timber rattlesnake, C. horridus horridus, the canebrake rattlesnake, C. horridus atricaudatus, or the largest of all rattlesnakes, the Eastern diamondback, C. adamateus, which is said to reach from six to nine feet in length.

Counting ‘Scuta’

Four Present U.S. Species

Based on Findlay E. Russell, Snake Venom Poisoning (New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1980), as redrawn in Laurence M. Klauber, Rattlesnakes (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 106-107.

The men saw only a few rattlesnakes while traversing the Columbia Plateau the autumn of 1805 because, Lewis surmised, the season was so far advanced. “Nor do I know,” he concluded, “whether they are of either of the four speceis found in the different parts of the United states, or of that species before mentioned . . . the prairie rattler . . . peculiar to the upper parts of the Missouri and it’s branches.” It is not clear what other species he was referring to, but it is possible that they were the Northern Pacific rattlesnake, now classified as C. viridis oreganus; the timber rattlesnake, C. horridus horridus; and the canebrake rattlesnake, C. atricaudatus (ay-tree-cow-DAY-tus, meaning “tough as steel”).

On this specimen Lewis counted “176 scuta on the abdomen and 17 half formed scuta on the tale.” Herpetologists don’t use the term scuta today, but call those parts ventral [belly] scales. The number of ventral scales corresponds to the number of vertebrae. Those on the tail are called subcaudal—beneath the tail—scales.[1]Information of George R. Zug, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 23 June 2003. Scutella, properly speaking today, are large, heavy scales found on the back of the rattlesnake’s head.[2]Roland Bauchot, ed., Snakes: A Natural History (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 1994), p. 14. Scutellum is a form of the Latin word for “shield”; it is also used in other natural … Continue reading

Where did Lewis learn to count “scuta”? From one of his pre-expedition mentors in Philadelphia, such as Benjamin Smith Barton? From Thomas Jefferson, who was also something of a naturalist? From childhood rambles near his homes in Virginia and Georgia?

Or did he glean it from the reference work published in London in 1764, Owen’s Dictionary, which was in their portable library? There, the “Rattle-snake” was described as:

a genus of serpents, having scuta that cover the whole under-surface of the body and tail, and having the extremity of the body terminated by a kind of rattle, formed of a series of urceolated [urn-shaped] articulations, which are moveable, and make noise. Of this serpent, there are two species, the greater one with scuta of the abdomen a hundred and seventy-two, of the tail twenty-one; and the lesser rattle-snake, having the scuta of the abdomen a hundred and sixty-five, of the tail twenty-eight. The larger is a very terrible, and at its full growth, a very large serpent, growing to eight feet in length, with a proportionable thickness . . . . This serpent is frequent in the woods of America: the bite is fatal, but it is easy to avoid it, the creature being sluggish, unless provoked, and giving notice before it bites by shaking its rattle.

The lesser species of this serpent grows to about seven feet in length, and in most particulars is like the former one, and its bite is equally mischievious.[3]A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences; comprehending all the branches of useful knowledge, with accurate descriptions as well of the various Machines, instruments, tools, figures, and … Continue reading

The emphasis on size and fearsomeness reflected the popular fascination during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with “charismatic” wild creatures such as this one.

Rattlesnake Bites

“Latet anguis in herba!”

“A snake lurks in the grass!”

Meanwhile, Clark and the rest of the Corps were working their way upriver. Clark complained:

the current excessively rapid and dificuelt to assend . . . great numbers of dangerous places, and the fatigue which we have to encounter is incretiatable, the men in the water from morning untill night hauling the cord and boats, walking on sharp rocks and round sliperey stones which alternately cut their feet and throw them down, not with standing all this dificuelty, they go with great cheerfulness, aded to those dificuelties the rattle snakes are inumerable & require great caution to prevent being bitten.

The previous Fourth, 4 July 1804, at Independence Creek near today’s Kansas City, Kansas, Clark reported that “a Snake bit Jo: Fields on the side of the foot which Swelled much.” Captain Lewis quickly applied a poultice of “Barks” to the wound. That would have been powdered “Peruvian Bark,” from the South American cinchona tree. It contains quinine, which would have been effective on malarial fevers, but was useless in any form against rattlesnake venom.

How serious might Field’s injury have been? Laurence Klauber has summarized the symptoms of the bite of a C. viridis viridis:

there is an immediate sensation like the sting of a wasp; there is little or no bleeding; a spreading feeling of numbness, especially at the tongue and lips; the tips of the fingers and toes tingle; there is a tendency to faint, and thereafter to remain in a coma for some time; nausea and vomiting are usually present; swelling begins about ten minutes after the bite, with discoloration, and continues with severe pain for thirty-six to forty-eight hours.[4]Laurence Klauber, Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, & Influence on Mankind (Abridged by Karen Karvey McClung; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 185.

Fortunately, although a rattlesnake bite is traumatic to both body and mind, it is seldom fatal to humans, but merely achieves just what the biter intends: It distracts and immobilizes a creature considered to be a threat to its safety. Five days after Field’s encounter, Sergeant Gass announced, “the man that was snake bitten is become well.”

Herbal Remedy

During the winter at Fort Mandan the explorers learned from Canadian trader Hugh Heney of an Indian topical medicine. In his journal for 28 February 1805, Clark described it as:

. . . a Root and top of a plant presented by Mr. Haney, for the Cure of mad Dogs Snakes &c, and to be found & used as follows vz [viz; videlicet]: . . . this root is found on high lands and asent of hills, the way of useing it is to Scarify the part when bitten to chu or pound an inch or more if the root is Small, and applying it to the bitten part renewing it twice a Day. the bitten person is not to chaw nor Swallow any of the Root for it might have contrary effect.

The plant Heney sent probably was the purple coneflower, Echinacea angustifolia, which is known to have been widely used by Plains Indians in treating various poisonous bites, including that of the rattlesnake.[5]Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1998), p. 205. Commonly called by such names as black sampson, comb plant, and snakeroot, it is still listed in the U.S. Pharmacopeia, and is among the most popular of all botanicals. Notwithstanding its durable and widespread reputation, perhaps based on the psychological potency of its obnoxious flavor, its effect on a rattlesnake bite is no better than Lewis’s “Peruvian barks.” Its range today extends from eastern Minnesota to western Montana, and from Saskatchewan to Texas. Lewis sent a specimen to Jefferson.[6]See the Twinleaf Journal of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Echinacea (e-kee-NAH-kee-a; often pronounced ek-i-NAY-she-a) is from the Greek word for hedgehog, a reference to the prominent receptacle … Continue reading

Rattlesnakes continue to endanger the Lewis and Clark Trail traveler. Here, a sign warns hikers at Crow Butte—down the Columbia River from Umatilla, Oregon. This editor and his young family have hiked there numerous times without any encounters—Ed.

Selected Encounters

Rattlesnake sightings and encounters, which began near the Manitou River in Missouri, were evidently too numerous to count, but the men killed at least seventeen before the expedition was over. There were several close calls, too. Lewis “trod within five inches” of one near the Judith River in Montana on 26 May 1805:

but being in motion I passed before he could probably put himself in a striking attitude and fortunately escaped his bite, I struck about with my espontoon being directed in some measure by his nois until I killed him.

Another close call occurred on 12 June 1805, when one of the men cordelling a canoe “cought one by the head in Catch’g hold of a bush on which his head lay reclined.”

On 11 July 1805, at the canoe-building camp upriver from Great Falls, a rattler struck at Private Whitehouse’s leg, but hit only his legging. “I shot it,” the soldier reported, “it was 4 feet 2 Inches long, and 5 Inches and a half around.” A month later, in the vicinity of the Gates of the Mountains, Private Whitehouse reported that:

Capt. Clark was near being bit by a rattle snake which was between his legs as he was Standing on Shore a fishing . . . he killed it and Shot Several others this afternoon.

It’s hard to tell, from these reports just how much danger any man was in. The striking distance of a prairie rattler varies according to several factors, including the species, its position relative to its prey, and how excited it happens to be at the instant of the strike. The principal determinant may be the reptile’s length, for according to Laurence Klauber, a rattler’s strike will rarely extend more than half its length, measured from the front of the anchor coil. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to estimate the actual length of any reptile without counting its ventral scales, and doing that to a snake-on-the-hoof is definitely unwise.

Equally important is the speed of the strike. In a series of tests using artificial prey, an adult prairie rattlesnake struck with an average speed of 8.12 feet per second—slower than a prizefighter’s punch.[7]Ibid., pp. 95-98.

Lore and Legend

For various reasons, the rattlesnake is surrounded by a large lore of legend. Perhaps it is the reptilian taciturnity, combined with the apparently torpid demeanor, both attributes veiling a supposedly sinister inclination. For instance, there’s the episode at Fort Mandan, wherein René Jusseaume, the French trader Lewis and Clark hired as an interpreter—notwithstanding that his own reputation was not unlike a rattlesnake’s[8]Clark characterized him on 27 October 1804, as “Cunin artfull an insoncear”—cunning, artful, and insincere.—who prescribed “a small portion of the rattle of the rattle-snake” to hasten Sacagawea‘s parturition. Lewis reported

Having the rattle of a snake by me, I gave it to him and he administered two rings of it to the woman broken in small pieces with the fingers and added to a small quantity of water . . . whether this medicine was truly the cause or not I shall not undertake to determine, but I was informed that she had not taken it more than ten minutes before she brought forth. Perhaps this remedy may be worthy of future experiments, but I must confess that I want faith as to it’s efficacy.

Then there is the story belonging to the copious literature on rattlesnake taming. Among the several hundred questions Nicholas Biddle posed to William Clark during their meeting in April of 1810 was: “Qu: as to tame rattle snakes in Rocky mountains.” His notes on Clark’s answer read as follows:[9]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (2nd ed., 2 vols., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:544.

Among Snake Indians in one of the towns a Snake Indian supposed to have been killed having been wounded & scalped by the Minnetarees of F. de Prairie [Atsinas] arrived having recovered on field of battle & escaped to woods. He brought with him two large rattle snakes whose teeth he had extracted. They were tamed by him wrapped themselves round his body . . . bosom &c . . . . knew him . . . boys amused thems[elve]s with sticks . . . the name of the Snake Indians got by their being remarkable for taming snakes of which they have many in their country.

Indian lore is said to include many such tales, and similar legends abounded in Colonial days, including reports of tamed snakes coming when called—perhaps symbolically triumphing over the serpent in the Garden of Eden.[10]Genesis 3:13-15.

Notes

| ↑1 | Information of George R. Zug, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 23 June 2003. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Roland Bauchot, ed., Snakes: A Natural History (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 1994), p. 14. Scutellum is a form of the Latin word for “shield”; it is also used in other natural sciences for elements characterized by that shape or function. |

| ↑3 | A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences; comprehending all the branches of useful knowledge, with accurate descriptions as well of the various Machines, instruments, tools, figures, and schemes necessary for illustrating them, as of the classes, kinds, preparations, and uses of natural productions, whether animals, vegetables, minerals, fossils, or fluids. &London: Printed for W. Owen, at Homer’s Head, in Fleet-street. MDCCLIV, s.v. “Rattle-snake.” |

| ↑4 | Laurence Klauber, Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, & Influence on Mankind (Abridged by Karen Karvey McClung; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 185. |

| ↑5 | Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1998), p. 205. |

| ↑6 | See the Twinleaf Journal of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Echinacea (e-kee-NAH-kee-a; often pronounced ek-i-NAY-she-a) is from the Greek word for hedgehog, a reference to the prominent receptacle scales at the center of the coneflower. The name of the species, angustifolia, is a Latin word meaning narrow leaf. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., pp. 95-98. |

| ↑8 | Clark characterized him on 27 October 1804, as “Cunin artfull an insoncear”—cunning, artful, and insincere. |

| ↑9 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (2nd ed., 2 vols., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:544. |

| ↑10 | Genesis 3:13-15. |