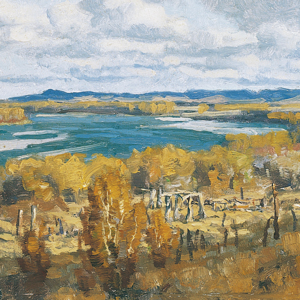

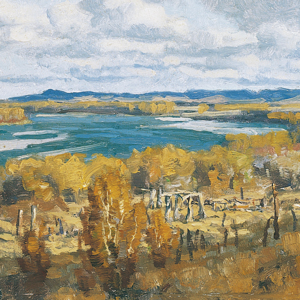

Mih-Tutta-Hangjusch, a Mandan village

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.[1]“Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, Mandan Dorf. Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, village Mandan. Mih-Tutta-Hangjusch, a Mandan village.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 12 June 2019. … Continue reading

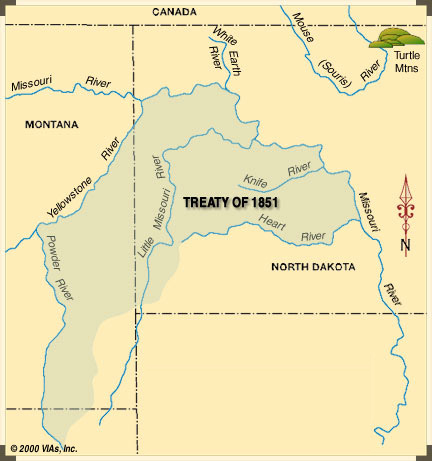

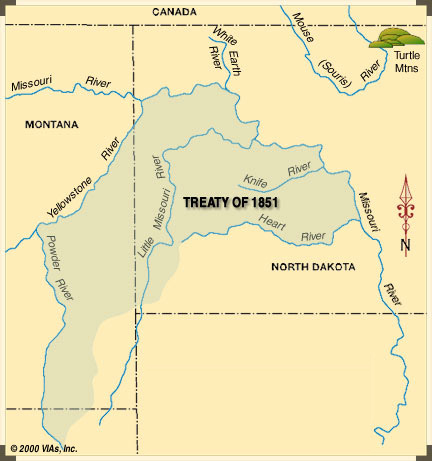

In the first record of European contact in 1738, La Vérendrye, reported nine villages of Mandan People living near the Heart River in present-day North Dakota.[2]Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 2 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1910), 797. When Lewis and Clark passed that river, they saw only the ruins of those villages. After the 1781 smallpox epidemic, the Mandan had moved into to a more defensible position in two villages immediately south of the Hidatsas at the Knife River. The Mandan-Hidatsa alliance had developed many years prior, and the two tribes previously shared their large hunting territory to the west.[3]W. Raymond Wood and Lee Irwin, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 349.

Prolific Traders

These Siouan-speaking people practiced horticulture and hunting in the manner of the Plains Village tradition. They were also prolific traders, exchanging their garden produce and acting as middlemen between European traders and other tribes including Assiniboines, Blackfeet, Crees, Crows, Pawnees, and—writes trader Pierre-Antoine Tabeau in one of his characteristic hyperboles—”an infinity of others.”[4]Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, Tabeau’s Narrative of Loisel’s Expedition to the Upper Missouri River, ed. Annie Heloise Abel, translated from French by Rose Abel Wright, (Norman: University of … Continue reading

When Lewis and Clark arrived in the fall of 1804, Mandan trade with Canadian-based commerce had long been established. For at least two decades European traders had intermarried and raised families in Mandan villages.[5]The Souris River route connected the Mandan villages with the English trading posts on the Assiniboine River. For more, see on this site, Souris River Trade Route. One notable trader living at the Knife River Villages, was Toussaint Charbonneau who joined the expedition as an interpreter and who more famously brought along his Lemhi Shoshone wife, Sacagawea.

Ceremonial and Religious Life

The Mandan people possessed a deep mythology and religious life. Lewis, Clark, and the others of the expedition glimpsed only a small portion, and understood even less.[6]For a fuller exploration into Mandan mythology and religion and the expedition members’ understandings of them, see Thomas P. Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark: Reflections of Men and … Continue reading

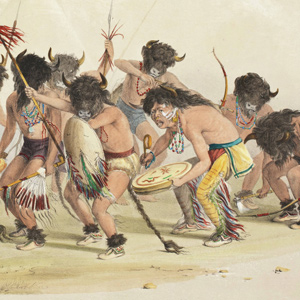

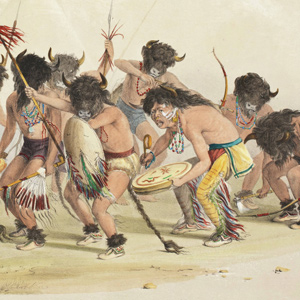

During the cold January days at Fort Mandan, the journalists tried to explain the Buffalo Dance and the Mandan practice of gaining power from elders by having them sleep with the younger man’s wife. On 5 January 1805, Clark says they sent one of the men to such a ceremony and that he was given four girls. On the 20th of that month, Patrick Gass and Joseph Whitehouse record a ritual of offering food to a buffalo head. Gass wrote, “Their superstitious credulity is so great, that they believe by using the head well the living buffaloe will come and that they will get a supply of meat.” Whitehouse also added:

The party who was at this Village also say that those Indians, possess very strange and uncommon Ideas of things in general, They are very Ignorant, and have no Ideas of our forms & customs, neither in regard to our Worship or the Deity &ca.

On 25 October 1804, Clark records the Mandan custom of cutting the first joint of a finger when mourning the loss of a relative. On 21 February 1805, the captains are told about the Mandan medicine stone, and on their return to St. Louis, Clark records the Mandan creation story (see 18 August 1806). Notably missing from the journalists accounts are personal and tribal bundles, the Okipa ceremony, Turtle Drums and a multitude of sacred beings.[7]The journalists’ role as ethnographers in the context of their stay at the Mandan villages is explored in James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians, Bison Book ed. (Lincoln: University … Continue reading

The Mythic Madoc Indians

In the years 1795–1797, James Mackay and John Evans explored the Missouri River between St. Louis and the Mandan Villages. Their supporter, the Spanish government, was eager to establish trade. Evans’s motivation was in search for the mythic Madoc Indians, but he also made maps. Traveling the same waterway in 1804, the captains continually confirmed the accuracy of the Evan’s maps and would not contribute significant geographic knowledge until after they left Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805.[8]For a comparison of Evans’ and Clark’s maps, see on this site, Clark’s Fort Mandan Maps.

Perhaps the Mandan people had difficulty understanding the Euro-American search for a North American tribe that was descended from Welsh Prince Madog—the mythic Madoc Indians. Jefferson specifically asked Lewis to look for such a tribe, and at the time of the expedition, the prime candidates were the Mandans. The people did have a genetic predisposition for premature graying, but little else to support the theory. The captains took a vocabulary of their language, but gave no opinion. The other journalists reporting hearing a brogue or seeing light complexions among various tribes they encountered. The Mandan connection may have faded away, but after his 1832 visit with the Mandan, artist George Catlin renewed the myth. Despite there being no solid archaeological, linguistic, or genetic evidence, many people today think the lost tribe has been, or will be, found.[9]Wood and Irwin, 350; Aaron Cobia, “Prince Madoc and the Welsh Indians: Was there a Mandan Connection?,” We Proceeded On, August 2011, Vol.37 No. 3, Page 16. Available at … Continue reading

After the Expedition

In 1837, the Mandans were nearly destroyed when the steamboat St. Peters brought smallpox to the Fort Clark village. In 1845, the Knife River Mandan and Hidatsa made a historic move to the Like-a-Fishook village, and the Fort Berthold trading post was soon built nearby. Years later, an American military post was added, and the Fort Berthold Reservation was established.

Today, the Mandan are part of the Three Affiliated Tribes also known as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation. Stories of notable members can be viewed on the page Meet the Three Affiliated Tribes. For a geo-political analysis of traditional land holdings, see Fort Berthold Reservation.

Synonymy

This limited synonymy is meant to help the Lewis and Clark reader. Spellings from the journals are enclosed in brackets.[10]Moulton, Journals, 3:201n5 and 202, fig. 4. For a full synonymy, see Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, 362–64.

Mandan People: Mandane, Mantannes, Mantons, Mendanne, Mandanne, Mandians, Mandols

Mututahank village: [Matootonha, Ma-too-ton-ka, Mar-too-ton-ha], Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, Métutahanke, Mitutahankish, Mitutanka, enumerated as First Mandan Village

Ruptáre village: [Roop-tar-hee, Roop-tar ha], Ruhpatare, Rùptari, Ruptadi, Nuptadi, Posecopsahe (Black Cat), East Village, enumerated as Second Mandan Village

Selected Pages and Encounters

Assessing the Legacy of Lewis and Clark

by Clay S. Jenkinson

The author proposes a few metaphors for the Lewis and Clark story, not in any definitive way, but merely to help us all think about the legacy of the expedition.

This Arikara leader rode upriver with the expedition in the weeks that followed to negotiate a peace settlement with the Mandan. In the spring of 1805 he went down river with the barge to St. Louis. After a series of delays, he went to Washington, DC, to meet with President Jefferson.

Posecopsahe (Black Cat)

In response to the captains’ requests for a Mandan-Arikara peace agreement, exclusive trade with St. Louis, and a Mandan delegation to visit Washington City, Posecopsahe initially gave favorable responses.

Sheheke and Yellow Corn

Sheheke and his wife, Yellow Corn, would visit Washington City at the request of the captains. It would be years before they could safely be returned to their people.

Meet the Three Affiliated Tribes

Interviews with tribal members

My name is Tex Hall. I’m the tribal chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes . . . the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation . . . here at Fort Berthold at present day New Town, North Dakota. I would like to speak a little Hidatsa because I am Mandan and Hidatsa.

Hidatsa Territory

Becoming the Fort Berthold Reservation

After leaving Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805, the expedition traveled for several days through Hidatsa territory. Much of that area would become the Fort Berthold Reservation of the Three Affiliated Tribes, a coalition of Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara.

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

Sheheke’s Delegation

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Sheheke’s diplomatic trip to Washington City and his difficult return home brought down the careers of at least two great leaders—himself, and Meriwether Lewis.

January 1, 1804

New Year's shooting contest

Winter Camp at Wood River, IL Clark stages a shooting contest with the locals and notes that two men (perhaps Reed and Windsor) were drunk. He meets with a new washer woman, and a visitor tells him about the Mandan Indians and their country. The captains begin their weather diaries.

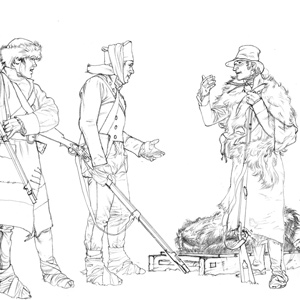

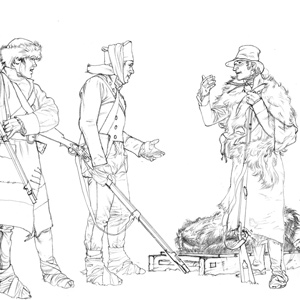

October 18, 1804

Passing the Cannonball

Fort Rice, ND Shortly after starting up the Missouri, they meet two traders who had recently been robbed. The two turn around and travel with the expedition. In passing the Cannonball River, a ‘cannon ball’ rock is selected for a new anchor.

October 19, 1804

Gangs of buffalo

Above Graner Bottoms, ND With a favorable wind, the expedition makes 17½ miles stopping near the mouth of the Little Heart River in present-day North Dakota. Along the way, they encounter large herds of bison and elk, golden eagle nesting areas, and an old Mandan village.

October 20, 1804

Pursuits and escapes

Heart River, ND Clark finds a Mandan village abandoned because of Sioux attacks. Pierre Cruzatte wounds a grizzly bear and a buffalo cow, and he is chased by both.

October 24, 1804

Mandan-Arikara council

Washburn, ND The morning brings snow and rain as the boats make seven more miles up the Missouri reaching a Mandan camp. The captains, Too Né, and a Mandan chief meet with ceremony and smoking.

October 25, 1804

Curious Indians

Below Stanton, ND The expedition continues up the Missouri River above present Washburn stopping often to talk with various Mandans. Due to numerous sandbars, finding a good channel becomes difficult. They hear news that some Assiniboines have recently killed a French trader.

October 27, 1804

Ruptáre Village

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND The expedition travels four miles among a complex of Mandan and Hidatsa villages. They find René Jusseaume living there and hire him as an interpreter.

Reaching the mouth of the Knife River on 27 October 1804, the expedition arrived in the midst of a major agricultural center and marketplace for a huge mid-continental region. The five permanent earth lodge communities there offered a panorama of contemporary Indian life.

October 28, 1804

Council postponed

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND The Indian council planned for today is postponed due to high winds. Nearby Indians visit none-the-less, and Posecopsahe (Black Cat), Clark, and Lewis look for a place to build winter quarters.

October 29, 1804

Mandan-Hidatsa-Arikara peace

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND The standard diplomatic speech is given at a council with the Mandans and Hidatsas. The captains ask them to also smoke the pipe of peace with Arikara Chief Too Né. Medals, flags, and clothing are given as gifts.

October 31, 1804

Black Cat speaks

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND Posecopsahe (Black Cat) gives a speech wishing for peace and returns two of the French traders’ stolen beaver traps. Lewis writes a letter to the North West Company bourgeois at Fort Assiniboine.

November 1, 1804

Dropping downriver

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND Clark takes a group down the river to find a suitable site for winter quarters. Lewis, with the main party, arrives at camp after dark.

November 12, 1804

Mandan history lesson

Fort Mandan, ND Sheheke (Big White), chief of the Mitutanka village, and his wife, likely Yellow Corn, visit Fort Mandan. She carries 100 pounds of meat and Sheheke tells the Mandan creation story.

November 18, 1804

The Mandan-Assiniboine trade alliance

Fort Mandan, ND Black Cat’s wife brings corn carried on her back, and he tells the captains how their promises sound much like the unfulfilled promises previously given by Spanish trader John Evans.

November 20, 1804

Diplomatic complications

Fort Mandan, ND Three chiefs from the Ruptáre village say that the Sioux will punish the Arikaras if they follow the captain’s peace initiatives. Charbonneau brings a large load of meat and furs, and the captains move into their room.

November 22, 1804

Domestic violence

Fort Mandan, ND At the interpreter’s camp just outside of Fort Mandan proper, an Indian threatens to kill his wife for having slept with Sgt. Ordway. On the Ouachita River, expedition leader George Hunter has a near-fatal accident.

November 27, 1804

Mandan deceptions

Fort Mandan, ND Lewis returns with two Hidatsa chiefs, and the captains learn that the Mandans and one fur trader have been telling lies to the Hidatsas to keep them away from the fort. In Philadelphia, an eccentric botanists asks why no trained botanists is on the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

November 30, 1804

A military reprisal

Fort Mandan, ND Responding to news of a deadly Sioux and Arikara attack on Mandan and Axaxawi Hidatsa hunters, Clark leads a military force to Mitutanka to gather warriors and pursue the Sioux. His intentions are appreciated, but he is convinced to abandon the plan.

December 1, 1804

Hudson's Bay Company visitor

Fort Mandan, ND George Henderson of the Hudson’s Bay Company visits, and Sgt. Ordway describes their business at the Knife River Indian villages. A delegation of Cheyennes and Arikaras arouse Mandan suspicions.

December 2, 1804

Cheyenne delegations

Fort Mandan, ND When four Cheyennes arrive, the captains give the standard diplomatic speech, gifts of tobacco, a flag, and demonstrations of many ‘curiosities.’ A letter of warning to the Sioux and Arikaras is also handed to the visitors.

December 7, 1804

Hunting buffalo

Fort Mandan, ND Some Mandans tell the captains that there is a large buffalo herd nearby, and Lewis organizes a group of hunters. Gass is impressed with the ability of the Indian hunters and their well-trained horses.

December 15, 1804

A Mandan game

Fort Mandan, ND Ordway and two others visit a Mandan village to trade for corn. There, they see men playing a game involving rolling a stone and sliding sticks across a large ice field.

December 23, 1804

A Mandan treat

Fort Mandan, ND Many Indians bring squash, corn, and beans. The wife of Little Raven cooks a Mandan treat for the captains while the enlisted men manage ‘large crowds’ in their quarters.

January 1, 1805

A new year at Fort Mandan

Fort Mandan, ND New Year’s day is celebrated with cannon fire and several men are allowed to visit a nearby Mandan village to celebrate and dance. Clark orders York to dance. The day is warm with rain but the night is cold and snowy.

January 4, 1805

Gifts for Little Raven

Fort Mandan, ND The weather warms enough to encourage hunters to go out. They kill a buffalo calf. Little Raven visits the fort, and he is given gifts.

January 5, 1805

The buffalo dance

Fort Mandan, ND With information gathered from traders and Indians, Clark works on his map of the west. He also describes the Mandan’s Buffalo Dance ceremony.

January 15, 1805

A lunar eclipse

Fort Mandan, ND In the early morning hours, celestial observations are made during a lunar eclipse. The captains receive their first Hidatsa visitors since November.

January 16, 1805

Hidatsa-Mandan jealousies

Fort Mandan, ND Warm weather melts the snow on the Fort Mandan roofs as the captains attempt to smooth over a spat between the Hidatsas and Mandans and broker peace between Seeing Snake and the Shoshone.

January 23, 1805

Making sleds

Fort Mandan, ND The men awake to four inches of fresh snow and go about their ‘common’ day. Sleds are made and traded for Indian beans and corn.

February 8, 1805

Wovles and Ravens

At Fort Mandan, Lewis entertains Posecopsahe (Black Cat) and his wife. Away from the Knife River Villages, Clark has a pen built to keep the wolves and ravens away from the harvest of the hunt.

February 16, 1805

Scorched earth

Fort Mandan, ND Lewis and his men continue their pursuit of a Sioux war party and come to an old Mandan village where the hunter’s cache of meat that has been pillaged and two lodges set afire.

February 20, 1805

Returning to the old village

Fort Mandan, ND Clark learns about the death of a very old Mandan Indian who is interned in a way that will return him to the “old village under ground.”

February 21, 1805

The Mandan medicine stone

Fort Mandan, ND Big White (Shekeke) and Big Man tell Clark that several Mandan men went to consult their “Medison Stone.” Lewis’s party returns with about 3,000 pounds of meat.

February 22, 1805

Fort Mandan rain

Fort Mandan, ND Fort Mandan receives its first rain since last November. Lewis’s hunting group rests while the others work to free the boats from the river’s snow and ice.

February 28, 1805

Arikara and Sioux news

Fort Mandan, ND Traders arrive with news of the Arikaras and Sioux and two plant specimens. About six miles from the fort, several men cut down cottonwood trees to make dugout canoes.

March 10, 1805

Migrating Indians

Fort Mandan, ND Visiting Indians tell the captains how the Mandan and Awaxawi Hidatsas were decimated by wars and smallpox, the reasons they banded together into five villages.

March 16, 1805

Native bead-making

Fort Mandan, ND Long-time Upper Missouri Villages trader Joseph Garreau shows the captains how the Arikara melt glass trade beads and re-make them more to their liking.

March 20, 1805

Moving the dugout canoes

Fort Mandan, ND Clark and six men join a large group at canoe camp and move four dugout canoes to the river’s edge. Lewis also discusses Jerusalem artichokes.

March 23, 1805

A Hidatsa vocabulary

Fur trade clerks Charles McKenzie and François-Antoine Larocque end their visit at Fort Mandan in present North Dakota. A Hidatsa man helps the captains record a vocabulary of his language.

March 29, 1805

Burning the winter grass

At the Knife River Villages, the Indians’ ability to jump from one ice cake to another while pulling dead bison from the Missouri amazes Clark. They also burn the dead winter grass to promote new growth.

April 2, 1805

Preparing Clark's journals

Clark works all day and into the night preparing his journals so that they can be sent to Thomas Jefferson. Mandan Chief Raven Man ends his extended stay at Fort Mandan and returns to his village, Ruptáre.

April 5, 1805

Loading the small boats

The men load the red and white pirogues and six new dugout canoes. Sgt. Patrick Gass recalls the Indian sexual practices experienced during his stay at Fort Mandan amongst the Knife River Villages.

August 11, 1806

Cruzatte shoots Lewis

White Earth River and Four Bears Village, ND While hunting elk, Pierre Cruzatte accidentally shoots Lewis through the buttock. Clark meets fur traders who share news of the barge, Indian wars, and shifting trade alliances.

August 14, 1806

Among old friends

Knife River Villages, ND Early in the day, the expedition greets their old friends at the complex of Hidatsa and Mandan villages at the Knife River. They meet with various chiefs, and Clark invites them to travel with the expedition to Washington City.

August 16, 1806

Parting gifts

Knife River Villages, ND Mandans gift more corn than the expedition boats can carry. As parting gifts, the swivel gun is given to Hidatsa Chief Le Borgne and the blacksmith tools to Charbonneau. Sheheke (Big White) agrees to go to Washington City.

August 18, 1806

A Mandan history lesson

Below the Heart River, ND Despite windy conditions, the expedition makes forty miles. As they pass abandoned village sites, Chief Sheheke (Big White) tells Clark of his people’s history. Near the Heart River, he tells the Mandan creation story.

August 21, 1806

Arikara Villages

Above Mobridge, SD At the upper and lower Arikara villages, several councils are conducted between the Mandans, various Arikara chiefs, and visiting Cheyennes. The captains see Rivet, one of their 1804 engagés, who says a chief from an earlier Washington City delegation has died.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, Mandan Dorf. Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, village Mandan. Mih-Tutta-Hangjusch, a Mandan village.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 12 June 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c441-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 2 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1910), 797. |

| ↑3 | W. Raymond Wood and Lee Irwin, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 349. |

| ↑4 | Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, Tabeau’s Narrative of Loisel’s Expedition to the Upper Missouri River, ed. Annie Heloise Abel, translated from French by Rose Abel Wright, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1939), 161. |

| ↑5 | The Souris River route connected the Mandan villages with the English trading posts on the Assiniboine River. For more, see on this site, Souris River Trade Route. |

| ↑6 | For a fuller exploration into Mandan mythology and religion and the expedition members’ understandings of them, see Thomas P. Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark: Reflections of Men and Wilderness (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003), ch. 1. |

| ↑7 | The journalists’ role as ethnographers in the context of their stay at the Mandan villages is explored in James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians, Bison Book ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 129–132. For ceremonies, see Wood and Irwin, 356–359. For more on the Medicine Stone, see Clay S. Jenkinson, A Vast and Open Plain: The Writings of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in North Dakota, 1804–1806 (Bismarck, North Dakota: State Historical Society of North Dakota, 2003), 222–23. |

| ↑8 | For a comparison of Evans’ and Clark’s maps, see on this site, Clark’s Fort Mandan Maps. |

| ↑9 | Wood and Irwin, 350; Aaron Cobia, “Prince Madoc and the Welsh Indians: Was there a Mandan Connection?,” We Proceeded On, August 2011, Vol.37 No. 3, Page 16. Available at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol37no3.pdf#page=18. |

| ↑10 | Moulton, Journals, 3:201n5 and 202, fig. 4. For a full synonymy, see Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, 362–64. |