Sign of Spring

Each of the red anthers on the stamens consists of two connected pollen sacs. The white style protruding below each flower’s stamens carries the stigma, which is the female organ that is receptive to pollen carried on the bodies of insects and humming birds.

Lewis immediately recognized this flower as a dog-toothed (or dog’s-tooth) violet, so he did not bother to examine it more closely, nor to describe it in detail. He mentioned it numerous times in the spring of 1806, perhaps because the genus was so widely known back home as a harbinger of spring that it could be used as botanical calendar to mark the progress of the season.

Clark had mentioned seeing it at Camp Dubois on 1 April 1804; that would have been Erythronium albidum Nutt., the white dog-toothed violet. The next reference was in Lewis’s daily Remarks on 9 April 1806, at Fort Clatsop; he likely saw either E. oregonum or E. revolutum. Lewis saw it again on 5 June 1806 near the Clearwater River. At that point it may have dawned on him that it might be different from the species he had known in the East, for he collected two specimens. There are, in fact, fifteen different species in the genus Erythronium, all but one in the U.S., with three of those in the Rocky Mountains region. The principal eastern species is Eurythronium americanum.

The common name by which Lewis knew it is somewhat misleading. Its familial affiliation is not with the violet (Violaceae) but the lily (Liliaceae). The allusion to a dog’s dental features arose either from the shape and color of its root, or its tapered petalous lips curled back to show its antherous “teeth,” or else its dentiform petals are the dog’s teeth. It all depends on one’s point of view. Other easterners might have known it by other names—fawn lily, perhaps from its appearance during the April-to-July birthing of deer; trout lily, for its coincidence with the fish’s spawning season; adder’s tongue, after the mildly poisonous reptile native to England and continental Europe; lamb’s tongue, yellow snake-leaf, or yellow snowdrop. Because it appears—in the Rockies, anyway—at the edges of receding snowbanks it has also earned the name glacier lily.

Frederick Pursh, in 1813, gave it its scientific name, Erythronium grandiflorum. The genus name comes from erythro, Greek for “red,” in reference to the color of the European species. The red anthers in the photograph above are not a consistent feature of all species of the genus. Grandiflorum means “large flower.” Its relative size is enhanced by the naked stem standing between only two graceful, shiny leaves.

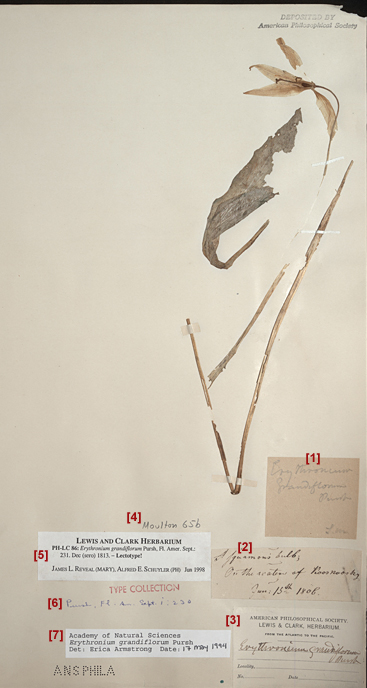

Lewis’s Lectotype Specimen

This is the specimen used by Frederick Pursh to write his scientific description and the Latin name. Specimen’s used in this manner are called lectotypes. Several of Lewis’s specimens collected during the Expedition served as lectotypes for future botanists. Numbers have been added to the photo that correspond to the note transcriptions and commentary offered below.

1. “Erythronium grandiflorum

Pursh

T.M.”

The initials T. M. are those of Thomas Meehan (1826–1901), a a botanist at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

2. “A squamous bulb;

On the waters of Kooskoosky

June 15th 1806.”

This annotation was written by Frederick Pursh. The word “squamous” means scaly. 15 June 1806 is the date on which Lewis collected this specimen on or near Hungery Creek, which is one of “the waters of Kooskoosky”—the Clearwater River.

3. “AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY

LEWIS & CLARK HERBARIUM.

FROM THE ATLANTIC TO THE PACIFIC.

Eurythronium grandiflorum

Pursh”

In 1818 most of Lewis’s plant specimens were deposited with the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, where they lay unnoticed until 1896, when Thomas Meehan found them and moved them to the Academy of Natural Sciences, where they remain on permanent loan. Note the stamp in the upper right-hand corner: “DEPOSITED BY the American Philosophical Society.”

4. “Moulton 65b” identifies the location of a picture of this specimen in the Herbarium of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, Volume 12 of The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, edited by Gary Mouton and published by the University of Nebraska Press (14 vols., 1983–2003).

5. “LEWIS AND CLARK HERBARIUM

PH-LC 86 Erythronium grandiflorum Pursh, Fl. Amer. Sept.:

231 . Dec (sero) 1813, — Lectotype!

James L. Reveal (MARY), Alfred E. Schuyler (PH), Jun 1998″

This annotation, written in June 1998, by James L. Reveal, of the University of Maryland (MARY), and Alfred E. Schuyler of the Academy of Natural Sciences (PH), identifies this specimen as number 86 of the 226 in the Lewis and Clark Herbarium (LC), and verifies that the specimen is the lectotype of this plant—that is, it is the one that Pursh used for his description, though it likely was more complete when he viewed it that it is today.

6. “TYPE COLLECTION

Pursh, Fl. Am. Sept. i:230.”

The stamped “TYPE COLLECTION” was applied by a curator at PH, possibly Francis Pennell (1886–1952), who may also have added the reference to Pursh’s Flora Americae Septentrionalis (Plants of North America), vol one, page 230.

7. “Academy of Natural Sciences

Erythronium grandiflorum Pursh

Det. Erica Armstrong Date 17 May 1994.”

This annotation affirms that a review of the history of this specimen up to 17 May 1994, was completed by curator Erica Armstrong.

Lewis’s Paratype Specimen

At right is a detail from the specimen Lewis collected on 8 May 1806, somewhere along the Clearwater River. This specimen, which is No. 65a in Moulton’s Herbarium of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (1999), is called a paratype. That is, it represents the same species as the specimen that was selected for the first scientific description (see above, comment 5), but was collected at a different time and place.

The label “Erythronium grandiflorum, Pursh var. parviflorum, Watson” was written by Benjamin Lincoln Robinson (1864-1935), curator of the herbarium at Harvard University to whom Thomas Meehan, of The Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, sent nearly all of the Lewis specimens he found at the American Philosophical Society. The Latin parviflorum means “little flower,” implying that this is a small variety of the “big flower” of the species grandiflorum. “Watson” was Sereno Watson (1826-1892), curator at Harvard prior to Robinson.

Pursh wrote the label at the bottom of the specimen sheet, copying the information from Lewis’s original, which he then discarded. It reads: “From the plains of Columbia near Kooskooskee R. May 8th 1806. the natives reckon this root as unfitt for food.” By “the natives” Lewis likely meant the Nez Perce people. In fact, numerous tribes once used the bulbs as a staple food, either raw or cooked, or dried and stored for winter use, and ate the two opposing basal leaves also. A few tribes found medicinal uses for them. Children regarded the small ends of the roots as candy. Women of the Thompson Indians of British Columbia are said to have used the corms as wagers in gambling.[1]Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1998), 227. Both black and grizzly bears also feed on the roots, as do rodents such as the Columbian ground squirrel. Lewis made no mention in his journal of having tasted the root himself.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of James L. Reveal in writing this article.

Notes

| ↑1 | Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1998), 227. |

|---|