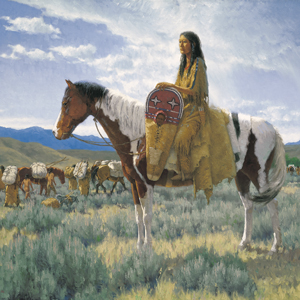

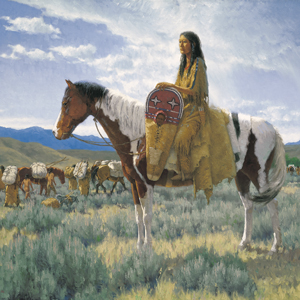

His Sister’s Son

© 2006 Michael Haynes. Reproduction prohibited without artist’s permission.

Watercolor, 24 by 36 inches. The artist may be contacted at Michael Haynes, Historic Art.

One of the best-known episodes in the whole story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition is the surprise reunion of the party’s “interpretess,” Sacagawea, with her brother, Cameahwait, the “Great Chief” of the Lemhi Shoshones. It was recorded briefly and matter-of-factly by Meriwether Lewis. In artist Michael Haynes’s conception of a brief and tender moment, otherwise undocumented, the proud young mother smiles broadly as if to tease little Jean Baptiste Charbonneau into responding similarly toward his uncle. Cameahwait, whom Clark called “a man of Influence Sence & easey & reserved manners, [who] appears to possess a great deel of Cincerity,” seems to be speaking softly to the 6-month-old baby. The Chief is wearing a tippet, that “most eligant peice of Indian dress,” much like the one he later gave to Meriwether Lewis.

The scene is inside the leather lodge Lewis purchased from Toussaint Charbonneau at Fort Mandan. Nightly from early April until mid-November, 1805, it sheltered the two captains and Clark’s servant, York, interpreters George Drouillard and Toussaint Charbonneau, Toussaint’s wife Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste. While Lewis searched for a suitable site for their winter encampment near the mouth of the Columbia River, the rest of the company fought to survive torrential wind and rain on Tongue Point near today’s Astoria, Oregon. Clark reported on November 28, “we are all wet bedding and Stores, haveing nothing to keep our Selves of Stores dry, our Lodge nearly worn out, and the pieces of Sales & tents So full of holes & rotten that they will not keep anything dry.”

Sacagawea and Cameahwait had not seen one another since their hunting camp near the Three Forks was attacked by Minitare (Hidatsa) warriors in about the year 1800. She and her sister, along with some other females and four boys, were captured by Hidatsa warriors and carried off to their village on the Missouri River near the mouth of the Knife in today’s North Dakota. On 28 July 1805 the Corps of Discovery camped on the exact spot where that attack took place.

—Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis as Ethnographer

If the Shoshones were fascinated by the men and equipment of the expedition, Meriwether Lewis was no less fascinated by them. They were the first Indians he had seen since the Mandans. They were about as close to being untouched by contact with white men as it was possible for any tribe to be at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Cameahwait’s people had perhaps seen a Spaniard or two; they had some trade goods of European manufacture, not much; they had three indifferent rifles.

The biggest effect of the white man on the Shoshones was horses, brought to the New World by the Spanish. Next came rifles, provided by the English and French to their trading partners on the Plains, the Blackfeet, Hidatsas and some others. As Cameahwait so movingly noted, the arms trade with the enemies of the Shoshones put his people at a terrible disadvantage and regulated their lives. They had to sneak onto the Plains, make their hunt as fast as possible, and retreat into their mountain hide-a-way, or as Lewis put it, “alternately obtaining their food at the risk of their lives and retiring to the mountains.”

The civilized world knew nothing about the Shoshones. In describing them, Lewis was breaking entirely new scientific ground. His account, written mostly at Camp Fortunate, is therefore invaluable as the first description ever of a Rocky Mountain tribe, in an almost pre-contact stage.

Lewis’s ethnography, if not up to the standards of academic ethnographers of the late twentieth century, was wide-ranging. His curiosity, his catholic interests, and his responsibility to report to Thomas Jefferson on the tribes he met combined to make for an informative, invaluable and altogether enchanting picture of Cameahwait’s people. Lewis covered their appearance, personal characteristics, customs, population, clothing, health, economy, the relations between the sexes, and politics. The richness of detail can only be hinted at here; interested readers are urged to go to the original journals for the full account.

Sacagawea’s People

The Shoshones were “deminutive in stature, thick ankles, crooked legs, thick flat feet and in short but illy formed, at least much more so in general than any nation of Indians I ever saw.” Their complexion was darker than that of the Hidatsas or the Mandans. As a consequence of the losses they had suffered in the spring to the Blackfeet, men and women alike had their hair cut at the neck: “This constitutes their cerimony of morning for their deceased relations.” Cameahwait had his hair cut close all over his head.

As to their demeanor “notwithstanding their extreem poverty they are not only cheerfull but even gay, fond of gaudy dress and amusements; like most other Indians they are great egotists and frequently boast of heroic acts which they never performed.” They loved to gamble. “They are frank, communicative, fair in dealing, generous with the little they possess, extreemly honest, and by no means beggarly.”

Cameahwait’s band numbered about 100 warriors, 300 women and children. There were few old people among them and so far as Lewis could tell the elderly were not treated with much tenderness or respect. As to relations between the sexes, “the man is the sole propryetor of his wives and daughers, and can barter or dispose of either as he thinks proper.” Most men had two or three wives, usually purchased as infant girls for horses or mules. At age 13 or 14 the girls were surrendered to their “soverign lord and husband.”

Sacagawea had been thus disposed of before she was taken prisoner, and her betrothed was still alive and living with this band. He was in his thirties and had two other wives. He claimed Sacagawea as his wife “but said that as she had had a child by another man, who was Charbono, that he did not want her.”

That was lucky, because Sacagawea was accompanying the expedition to the Pacific. Neither Captain Lewis nor Captain Clark ever thought to discuss the matter in his journal, so it is unclear whether she chose to leave her people after a reunion of less than a month, or Charbonneau forced her to come along. Since she had never been in the territory they were entering, and so could recognize no landmarks, and as her linguistic abilities would be of little help with the Nez Perce or any other tribe west of the mountains, the captains had no pressing need to bring her along. One would like to think that the question of whether she should stay with the expedition never came up, that she was by now so integral a member of the party that it was taken for granted that she would remain with it.

Females

Lewis noted, with disapproval, that the Shoshones “treat their women but with little rispect, and compel them to perform every species of drudgery. They collect the wild fruits and roots, attend to the horses or assist in that duty, cook dreess the skins and make all their apparal, collect wood and make their fires, arrange and form their lodges, and when they travel pack the horses and take charge of all the baggage; in short the man dose little else except attend his horses hunt and fish.”

Lewis failed to note that the warriors had to be always prepared to defend the village, which required them to be constantly on the alert, with their hands free. He did point out that the men had their best war horse tied to a stake near their lodges at night.

“The man considers himself degraded if he is compelled to walk any distance,” Lewis noted. He did not add that in this they were very like Virginia gentlemen. The literal translation of Cameahwait, as best Lewis could make it out, was “One Vho Never Walks.”

“The chastity of their women is not held in high estimation,” Lewis wrote. The men would barter their wives’ services for a night or longer, if the reward was sufficient, “tho’ they are not so importunate that we should caress their women as the siouxs were and some of their women appear to be held more sacred than in any nation we have seen.” Lewis ordered his men to give the Shoshone braves “no cause of jealousy” by having a sexual relationship with their women without the husband’s knowledge and consent. To prevent such affairs altogether, he recognized, would be “impossible to effect, particularly on the part of our young men whom some months abstanence have made very polite to those tawney damsels.”

Venereal Diseases

Knowing that the Shoshones had no contact with whites, Lewis wrote that “I was anxious to learn whether these people had the venerial.” His purpose was immediate—he had the health of his men in mind—but also scholarly. One of the oldest questions in medical history, still a subject of debate today, was whether syphilis originated in the Americas and spread to Europe after 1492, or was native to Europe and spread to the North American Indians by Europeans.

Through Sacagawea, Lewis made inquiries as to the presence of venereal disease among the Shoshones. He learned that it was a problem “but I could not learn their remedy; they most usually die with it’s effects.” So far as he was concerned, “this seems a strong proof that these disorders bothe gonaroehah and Louis venerae are native disorders of America.”[1]Lues venera is Latin for “syphilis.” Gonorrhea was often confused with syphilis at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but Lewis here made a clear distinction. Moulton, Journals, … Continue reading

But it was not conclusive, as Lewis realized, because the Shoshones had suffered much from the smallpox “which is known to be imported,” so they must have contracted it from other tribes that did have intercourse with white men. They might have contracted venereal disease in the same manner. Still, the Shoshones were “so much detatched from all communication with the whites that I think it most probable that those disorders [venereal disease] are original with them.”

Clothing

“the most eligant peice”

Meriwether Lewis wearing the tippet Cameahwait gave to him

Collection of the New York Historical Society

Painting by Charles B. J. F. de Saint Mémin (1770–1852). Watercolor, black ink, and graphite with touches of red gouache on heavy paper, mounted on card, 6 1/8 x 3 3/4 in. (15.6 x 9.5 cm ). Gift of Ethel McCullough Scott, John G. McCullough, and Edith McCullough Heaphy, Courtesy New York Historical Society, emuseum.nyhistory.org/objects/42180/meriwether-lewis-17741809-in-frontiersmans-regalia.

One part of Shoshone culture Lewis could observe and describe without having to go through a translation chain or Drouillard’s Plains Sign Language was clothing and general appearance. He wrote at great length about the Shoshone shirts, leggings, robes, chemises and other items, about their use of sea shells, beads, arm bands, leather collars, porcupine quills dyed various colors, earrings and so forth.

Lewis pronounced the tippet of the Shoshones “the most eligant peice of Indian dress I ever saw.” It was a sort of cloak made of dressed otter skin to which 100 to 250 rolls of ermine skin were attached. Cameahwait gave him one,[2]See Lewis’s Shoshone Tippet. which he prized (see figure). Footwear could also be ornamental. “Some of the dressy young men,” Lewis noted, “orniment the tops of their mockersons with the skins of polecats [skunks] and trale the tail of that animal on the ground at their heels as they wallz.”

Economy and Material Culture

For all that he wrote on clothing and customs, Lewis was most interested in Shoshone economics and politics. Here his goal was specific, to integrate the tribe into the trading empire the United States was going to create in Louisiana and beyond the mountains. The first requirement was a general peace along the Missouri River and in the mountains, but of course the Shoshones needed no prodding in that direction. They were not aggressors, but victims.

What the Shoshones could contribute to the overall goal was ermine, otter, and other exotic skins of the mountain animals, if they could be taught to trap and if they could be made dependent on a steady flow of the white man’s goods. The Shoshones were so desperately poor that there was almost no economy to speak of. In the spring and summer they lived on salmon, in the fall and winter on buffalo.

That they could successfully hunt buffalo was thanks to their horses, the sole source of wealth among them. Having few to no rifles, without horses they would have been indifferent hunters at best. On August 23, Lewis watched a dozen young warriors pursuing mule deer from horseback. The chase covered four miles and “was really entertaining.”

Shortly after noon the hunters came in with two deer and three pronghorns. To Lewis’s surprise, there was no division of the meat among the hunters. Instead the families of the men who had made the kill took it all. “This is not customary among the nations of Indians with whom I have hitherto been acquainted,” Lewis wrote. “I asked Cameahwait the reason why the hunters did not divide the meat; he said that meat was so scarce with them that the men who killed it reserved it for themselves and their own families.”

Their implements for preparing food and eating were primitive. They had neither ax nor hatchet to cut wood; instead they used stone or elk’s horn. Their utensils consisted of earthen jars and spoons made of buffalo horn. Lewis did an inventory of the metal objects possessed by Cameahwait’s people: “a few indifferent knives, a few brass kettles, some arm bands of iron and brass, a few buttons, worn as ornaments in their hair, a spear or two of a foot in length and some iron and brass arrow points which they informed me they obtained in exchange for horses from the Crow or Rocky Mountains Indians.” Any people so primitive that they were forced to trade horses for a few metal arrowheads obviously needed to get into a more extensive trading system.

Warrior Males

What the Shoshones valued above all else, and depended on absolutely, was the bravery of their young men. Their child-rearing system was designed to produce brave warriors. “They seldom correct their children,” Lewis wrote, “particularly the boys who soon become masters of their own acts. They give as a reason that it cows and breaks the Sperit of the boy to whip him, and that he never recovers his independence of mind after he is grown.”

In politics, they followed not the oldest or wisest or the best talker, but the bravest man. They had customs, but no laws or regulations. “Each individual man is his own soveriegn master,” Lewis wrote, “and acts from the dictates of his own mind.”

From this fact sprang the principle of political leadership: “The authority of Cheif [is] nothing more than mere admonition supported by the influence which the propiety of his own examplery conduct may have acquired him in the minds of the individuals who compose the band. the title of cheif is not hereditary, nor can I learn that there is any cerimony of instalment, or other epoh in the life of a Cheif from which his title as such can be dated. in fact every man is a chief, but all have not an equal influence on the minds of the other members of the community, and he who happens to enjoy the greatest share of confidence is the principal Chief.”

Since bravery was the primary virtue, no man could become eminent among the Shoshones “who has not at some period of his life given proofs of his possessing [it].” There could be no prominence without some war–like achievement, a principle basic to the entire structure of Shoshone politics.

These observations led Lewis to an insight into the problems the Americans were going to have in integrating not just the Shoshones but all the Indians west of the Mississippi River into their trading empire. He recalled the day at Fort Mandan when he was explaining to the Hidatsa chiefs the advantages that would flow to them from a general state of peace among the nations of the Missouri. The old men agreed with him, but only because they “had already geathered their havest of larals, and having forceably felt in many instances some of those inconveniences attending a state of war.” But a young warrior put to Lewis a question that Lewis could not answer: “[He] asked me if they were in a state of peace with all their neighbours what the nation would do for Cheifs?”

The warrior went on to make a fundamental point: “The chiefs were now oald and must shortly die and the nation could not exist without chiefs.”

In two sentences, the Hidatsa brave had exposed the hopelessness of the American policy of inducing the Missouri River and Rocky Mountain Indians to become trappers and traders. They would have to be conquered and cowed before they could be made to abandon war. Jeffersons’ dream of establishing through persuasion and trade a peaceable kingdom among the western Indians was as much an illusion as his dream of an all-water route to the Pacific.

This was a great disappointment, but it could not be helped. It was characteristic of the men of the Enlightenment to face facts. Lewis’s ethnology helped establish the facts. It was therefore a great contribution to general knowledge—exactly the kind of contribution Lewis berated himself for not making in his thirty-first birthday musings.

Selected Pages and Encounters

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

On the day before he left Camp Fortunate for the last time, Lewis described, with typical attention to detail, the usual caparison of the Shoshone Horse”–halter, saddle, and all other trappings.

January 16, 1805

Hidatsa-Mandan jealousies

Fort Mandan, ND Warm weather melts the snow on the Fort Mandan roofs as the captains attempt to smooth over a spat between the Hidatsas and Mandans and broker peace between Seeing Snake and the Shoshone.

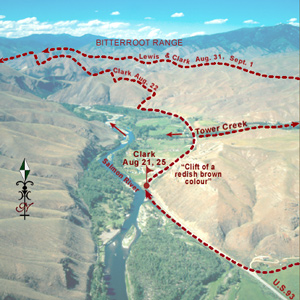

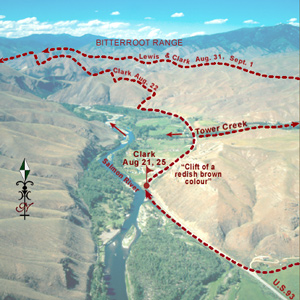

July 16, 1805

The first gate: Tower Rock

The expedition reaches their ‘first gate’ of the Rockies. Lewis climbs Tower Rock to get a better view. Both captains see recent signs of Indians, and they hope a Shoshone encounter is imminent.

August 11, 1805

First Shoshone encounter

Shoshone Cove and Beaverhead River, MT Lewis has his first Shoshone encounter. He tries several methods to persuade the warrior to meet with him but is unsuccessful. The main party works the canoes up the Beaverhead River past 3000 Mile Island.

When Cameahwait took Lewis into the shelter of the only leather lodge his people had been able to save from the Hidatsas’ depredations of the previous spring, Lewis knew for sure he was among good friends.

Meeting the Shoshones

by Joseph A. Mussulman

A few more Shoshones came in sight. Making all the benevolent signs and sounds he could think of, pondering ways to bring the wary Indians within talking distance, Lewis finally touched the hand of an elderly woman, and the spark of international friendship was struck.

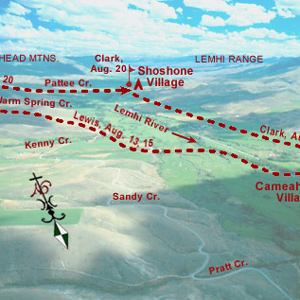

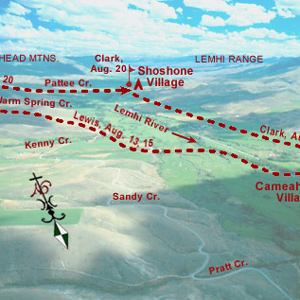

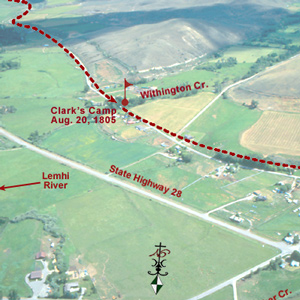

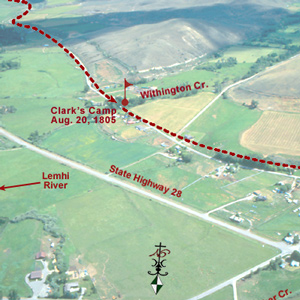

August 13, 1805

Shoshone diplomacy

Shoshone Village, ID and Clark’s Lookout, MT In the Lemhi River valley, Shoshone diplomacy includes greetings, a flag presentation, a pipe ceremony, and revelry late into the night. Back on the Beaverhead River, Clark takes bearings from Clark’s Lookout, and several men fish.

August 14, 1805

Asking for Shoshone help

Lemhi River, ID and Rattlesnake Cliffs, MT At a village on the Lemhi River, Lewis asks for the use of Cameahwait’s horses and people to bring the expedition’s baggage over the Continental Divide. Back on the Beaverhead River, the men ache from having to haul the canoes over rocks in the cold river.

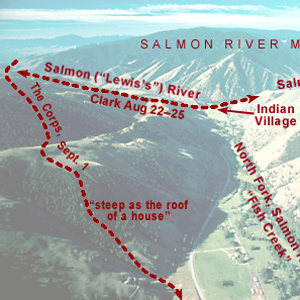

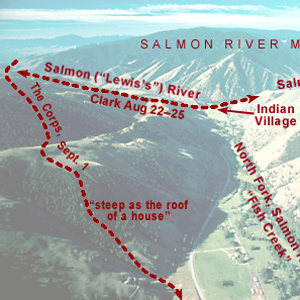

Cameahwait’s Geography Lesson

by J. I. Merritt

When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark encountered the Shoshone Indians in August 1805, one or the other—or more likely both, sat down with Cameahwait, the chief of the tribe’s Lemhi band, to learn as much as possible about the region’s geography.

Pretending to have been insulted by their accusation, Lewis pompously declared that “if they continued to think thus meanly of us…they might rely on it that no whitmen would ever come to trade with them or bring them arms and amunition.”

August 15, 1805

Reluctant Shoshone helpers

Shoshone Cove and Clark’s Canyon, MT Lewis discovers that the Lemhi Shoshones have become suspicious of his motives and are reluctant to travel with him. Eventually, most of the village crosses Lemhi Pass, and they all camp in Shoshone Cove. The main party suffers through another day to reach Clark’s Canyon.

August 16, 1805

Too many worries

Fortunate Camp, MT When Clark fails to arrive at the forks of the Beaverhead, Lewis worries about the fate of the expedition. The Lemhi Shoshones worry that they have been led into a trap. The main party comes to within a day’s travel of Fortunate Camp.

Cameahwait and some of his people agreed to help the Corps of Discovery carry its baggage over the divide. In the early afternoon. “We now dismounted,” wrote Lewis, “and the Chief with much cerimony put tippets about our necks such as they temselves woar.”

August 17, 1805

Fortunate Camp reunions

Fortunate Camp, MT Clark brings the dugout canoes up the Beaverhead River and meets Lewis and the Lemhi Shoshone Indians at what they would later call Fortunate Camp. Sacagawea is reunited with old friends and family, and negotiations for horses commences.

August 19, 1805

Trading for a mule

Lemhi River, ID and Fortunate Camp, MT Clark’s heads towards the Salmon River and trades for a mule. Lewis starts a multi-day essay describing Shoshone lifestyle and manners. Sacagawea’s first husband extracts payment from Charbonneau.

Lewis was still at Camp Fortunate directing the digging of a cache and the making of packs and pack-saddles for the portage across the divide. Meanwhile, Clark and his contingent left to see whether the Salmon River was as bad as Cameahwait had said.

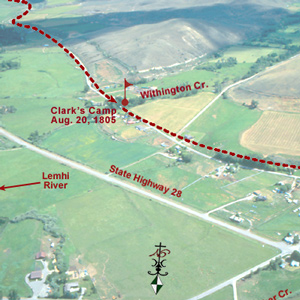

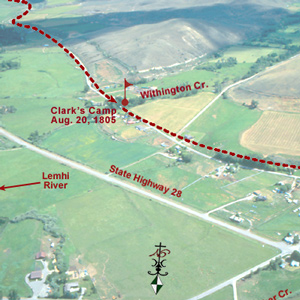

August 20, 1805

Toby shows the way

Fortunate Camp, MT and Lemhi River, ID Toby shows Clark the way down the Lemhi River. At Fortunate Camp, Lewis has a cache dug. Pack saddles are made from old boxes and oars.

August 21, 1805

Drouillard gives chase

Tower Creek, ID and Fortunate Camp, MT When a Lemhi Shoshone takes a rifle, Drouillard gives chase. At Fortunate Camp, the cache is completed and saddles and baggage are ready to be packed by horse. Clark explores the Salmon River and names it Lewis’s River.

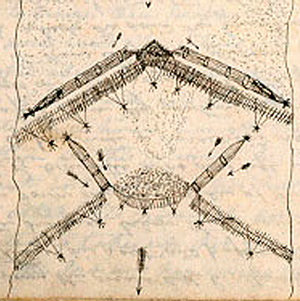

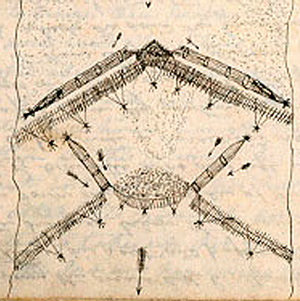

Clark visits a Shoshone camp on the west bank of the Lemhi River near today’s Salmon City, where he and his men are fed on “Sammon boiled, and dried Choke Cher[rie]s,” and taken on a sight-seeing trip to the nearby permanent fishing weirs.

August 22, 1805

Cameahwait's band arrives

Salmon River, ID and Fortunate Camp, MT Midday, Cameahwait’s band arrives at Fortunate Camp, and he and Lewis exchange food and horses. On the Salmon River, steep hills and mountains hem in Clark’s scouting party. Clark describes Clark’s Nutcracker, a bird new to science.

Lewis learned about three unfamiliar species of edible roots–a bushel of them altogether. The Shoshones who were encamped nearby helped him sort them out, and told him how they were customarily prepared.

August 23, 1805

The River of No Return

Salmon River, ID and Fortunate Camp, MT Leaving horses and most of his detachment behind, Clark and Toby climb a mountain spur where Clark sees the futility of canoeing the Salmon River, the River of No Return. At the request of Cameahwait, Lewis waits another day at Fortunate Camp before starting the portage over the Rocky Mountains.

August 24, 1805

Leaving Fortunate Camp

Salmon River, ID and Shoshone Cove, MT Lewis barters for three horses and a mule, and Charbonneau buys a horse for Sacagawea. With the help of Shoshone women, they start carrying baggage over the continental divide. Clark considers three alternate plans for reaching the Pacific Ocean.

August 25, 1805

A change of plans

Tower Creek, ID and Shoshone Cove, MT Lewis is shocked to learn of a change in Shoshone plans. Clark returns to his Salmon River camp of 21 August 1805.

August 26, 1805

Past the Great Divide

Lemhi River Valley, ID Having finally portaged all the baggage past the great divide, Lewis writes his last regular journal entry for the year, worried how they will cross the Bitterroot Mountains. Clark’s group moves to a Lemhi Shoshone village.

August 27, 1805

Flag ceremony

Lemhi River Valley, ID After a flag ceremony at the Upper Lemhi village, Lewis commences horsetrading. In the evening, the Lemhi Shoshones dance and sing. Further down the Lemhi River, Clark’s group hunts while waiting for Lewis to arrive.

August 28, 1805

A letter exchange

Lemhi River Valley, ID Sgt. Gass delivers a letter from Clark to Lewis and then returns twelve miles to the lower Lemhi village with Lewis’s reply. Lewis finds the prices paid for horses is rising.

August 29, 1805

Upper Village reunion

Lemhi River Valley, ID Clark takes a small group to the Upper Lemhi Village where Lewis is trading for horses. Clark trades his pistol for a horse.

August 30, 1805

Leaving the Shoshone

Lemhi River Valley, ID The corps and their Lemhi Shoshone guides head down the Lemhi River bound for the Pacific Ocean. Clark trades his fusil musket for a horse.

August 31, 1805

Leaving the Lemhi

Tower Creek, ID The expedition leaves early in the morning and soon arrives at the fish weirs where Sgt. Gass has been camped. They pick him and one man up, buy several salmon, and head down the Salmon River. They turn up Tower Creek and in four miles, make camp.

September 1, 1805

Up the North Fork Salmon River

North Fork Salmon River, ID People and horses climb out of Tower Creek, crosses high hills, descend to the North Fork Salmon River, and encamp near present-day Gibbonsville, Idaho.

June 20, 1806

Alternate plans

At Salmon Trout Camp on the Northern Nez Perce trail, the captains consider alternative routes to cross the Rocky Mountains. They decide to return to Weippe Prairie and wait for more snow to melt.

June 23, 1806

Three Nez Perce guides

While waiting at Weippe Prairie for mountain snow to melt, the hunters imitate bleating fawns to call in the does. Three Nez Perce guides arrive, and all is made ready to cross the Bitterroot Mountains.

August 15, 1806

Broken promises of peace

Knife River Villages, ND The captains here of several broken promises of peace among tribes they had worked with on the outward journey. Colter asks to leave the expedition so that he can go back west with two fur trappers.

Notes

| ↑1 | Lues venera is Latin for “syphilis.” Gonorrhea was often confused with syphilis at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but Lewis here made a clear distinction. Moulton, Journals, 5:125. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Lewis’s Shoshone Tippet. |