Four portraits and one statue by five different artists show a diverse interpretation of the likeness of William Clark.

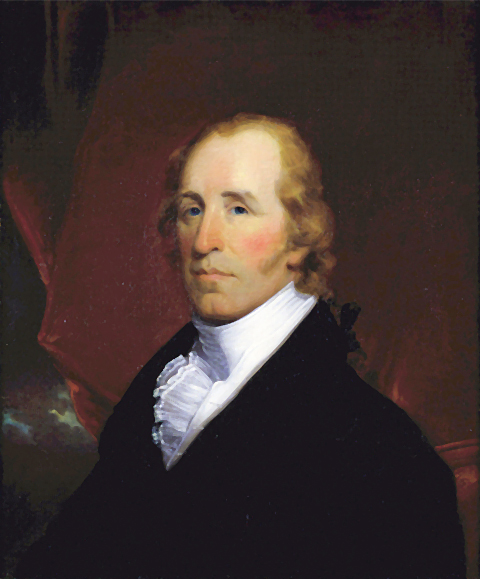

Peale’s Portrait

William Clark (1810)

Oil on canvas, 23-1/4 x 18-1/8 inches. Courtesy Independence National Historic Park.

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), was famous not only as an artist but also as the founder and curator of “Peale’s Museum” in Philadelphia, which contained his remarkable collection of natural history specimens and more than one hundred of his own portraits of famous contemporaries.

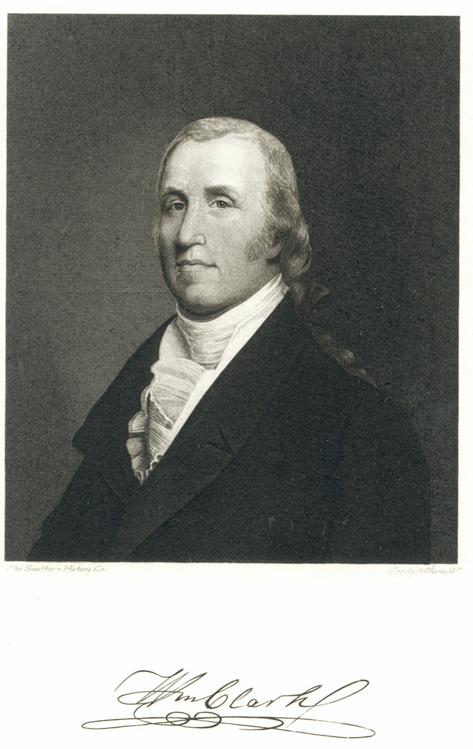

Mémin’s Portrait

Purportedly William Clark (1810)

by Charles B. J. F. de Saint Mémin (1770–1852)

Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

A round the middle of the eighteenth century the hobby of a French finance minister named Étienne de Silhouette (1709–1767) initiated a trendy market for paper-cutout “shadow portraits” in black-and-white, or the reverse. They were simple and cheap, like the minister’s economic theories, and reportedly more popular.

The appeal of the new “silhouette” gained impetus in the late 1770s with the creation of a pseudoscience called physiognomy, founded by Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801), and based on the proposition that the shape of one’s profile reflected the owner’s innate moral and behavioral makeup. The next step toward meeting the demand was the technological and representational enhancement of profile portraiture using the camera obscura and other drawing aids such as the pantograph, a German invention dating from 1631, with which anyone could enlarge or reduce any drawing. In 1788, Gilles-Louis Crétien (1754–1811), a cellist in the court orchestra of Louis XVI, invented the physiognotrace, with which even a person without any artistic talent whatsoever could create an accurate profile portrait—in four minutes!

In 1793, twenty-three-year-old Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, a royalist refugee from the French Revolution, arrived in America, studied drawing briefly, and taught himself engraving. In 1796, with his own improvement of Crétien’s physiognotrace, he set up his own business as a profile portraitist, quickly gaining fame and fortune as a facile, if not gifted, engraver. For twenty-five dollars the subject received the original drawing, the engraved copper plate of it, and a dozen copies of the engraving, all accurate with what we might imagine was near-photographic exactitude in terms of facial features, hair styles, and clothing.

Over a period of eighteen years, until he returned to France after the fall of Napoleon, he produced portraits of more than a thousand American subjects, including George Washington, Paul Revere, Thomas Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and Indians such as the Mandan chief Sheheke (Big White) and Yellow Corn. Like a great many other profile portraitists, including the designers of Indian peace medals, he posed his subjects in patrician attitudes within circular borders, in imitation of ancient Roman coins.

In 1802 a Philadelphia lawyer named William Barton asserted that Saint-Mémin’s profiles were strikingly true-to-life.[1]See “Federal Profiles, Saint-Mémin in America,” at http://www.educate.si.edu/migrations/portrait/npg.html In 1969 historian Paul Cutright concluded, however, that Charles Willson Peale’s oil paintings “probably come closer to portraying accurately the features of the two explorers than any other likeness extant.”[2]Paul R. Cutright, “Lewis & Clark: Portraits and Portraitists,” Montana, Magazine of Western History, XIX, 2 (April 1969), 39.

Jarvis’s Portrait

William Clark (ca. 1810)

by John Wesley Jarvis

Oil on canvas, 29-3/4 x 25-1/8 inches. Courtesy Missouri Historical Society Collections, St. Louis.

This portrait was also painted in or about 1810, when Clark went East from St. Louis to meet with Nicholas Biddle, whom he had engaged to write the paraphrase of the captains’ expeditionary journals. The painting purportedly was the work of the eccentric English-born American artist John Wesley Jarvis (1780-1840). John O’Fallon, Clark’s nephew, confirmed that Jarvis’s image was generally considered his uncle’s truest likeness. Several copies are said to have been made for other members of the Clark family and, like Peale’s painting of him, it was also copied by engravers for use as illustrations in books and articles.

Sometime in the late 1800s, it is thought, a steel-plate engraving was produced as a near-duplicate of an oil portrait owned by the Clark family—probably the one by John Wesley Jarvis (see above). Apparently it was intended for publication in a book on the history of the State of Missouri. For nearly a hundred years the plate remained in the estate of William Clark’s granddaughter, Julia Clark Voorhis. Much of that collection was acquired by the Missouri Historical Society, including such items as the elkskin-bound diary in which Captain Clark recorded his experiences and observations at Fort Clatsop. During the bicentennial of the expedition, Peyton C. “Bud” Clark, a direct descendant of General Clark, purchased several of the items remaining in the Voorhis collection, which was then owned by Valerie Anderson, a descendant of the attorney who had handled the Voorhis estate. Among them was the steel-plate engraving of Clark’s 1810 portrait, from which Bud Clark had an edition of 100 copies printed.

Harding’s Portrait

William Clark (ca. 1820)

Chester Harding

Oil on canvas, 94 x 60 inches. From the Collections of the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri, St. Louis, Gift of the St. Louis County Court.

Seven years after the Expedition’s return, President Madison appointed Clark to be governor of a vast northern expanse of the Louisiana Purchase then known as Missouri Territory. In 1820, immediately after Congress admitted a small segment of the Territory into the Union as the twenty-fourth state, he entered the electoral race for its governorship. Abruptly he was called to Fincastle, Virginia, to the bedside of his wife Julia (“Judith,” as in Judith River), who was mortally ill with breast cancer. He arrived six days after she died. Upon his return to St. Louis he learned that his opponent, his friend and former associate Alexander McNair had defeated him by almost three-quarters of the vote, borne on the fresh tide of democratic populism. His brand of Enlightenment-bred republicanism had been deposed.[3]William E. Foley, Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), Chapter Eight, “Mr. Governor.”

Sometime during those dark months he permitted a promising 28-year-old artist named Harding, who just happened to be in St. Louis, to portray him at the moment he left the governor’s office for the last time. Harding was equal to the challenge—the opportunity. The Governor has just risen from his chair, and pauses to contemplate his future. Harding captures the dignified stance and attire consistent with Clark’s aristocratic birthright. Beneath his graying hair, still tied in the queue he had worn as a young officer, shines the stoic mien that he habitually wore, the lips that could spring to an ever-ready smile or laugh; eyes that could study, measure and assimilate all he observed. A man of honor and distinction, his right hand grasps a book of some sort of knowledge he might have pursued, while over his shoulder and far to the west, the sun sets beyond the wide Missouri and the Rockies—”those tremendious mountanes” where he had endured some of his most harrowing days of his life.

The shock of personal tragedy, combined with the humiliation of defeat and removal from public service, made deeper by the threat of financial hardship, was mercifully short-lived. He was soon reappointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs. In September of 1821, 51-year-old William Clark wed a young widow of long acquaintance, Harriet Kennerly.

This painting, as well as two likenesses of the American hero Daniel Boone that he painted during the same visit to Missouri, helped to launch the Massachusetts-born Chester Harding (1792-1866) into a successful career as a professional artist. His output of more than 1,000 portraits included those of many of the most important figures in American history, such as Senator Daniel Webster (two) and Webster’s prominent colleague Henry Clay, the Supreme Court’s Chief Justice Marshall, and the poet and landscape artist Washington Allston.

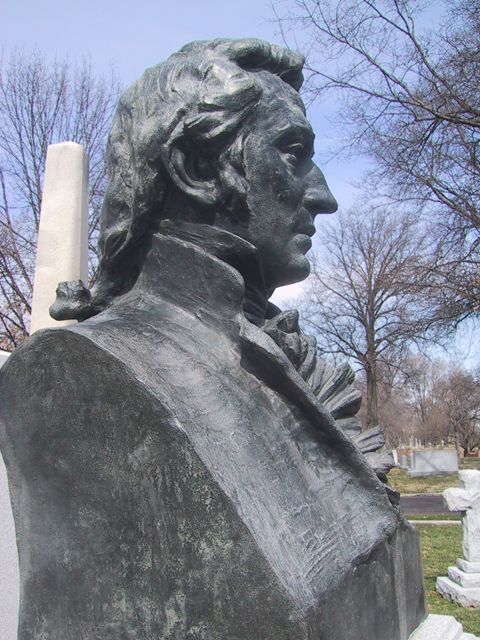

Partridge’s Sculpture

William Clark

William Ordway Partridge

Photo by VIAs Inc. © 2000

When General Clark died in 1838 his remains were interred on the farm of his nephew, John O’Fallon. In 1860, they were moved, along with those of his three deceased children, his second wife, Harriet, and Jefferson Kearney Clark, to Bellefontaine Cemetery in North St. Louis, where they were placed beneath a stately granite obelisk on a knoll overlooking the Mississippi River. The bronze bust, sculpted by William Ordway Partridge of New York (also known for his 1922 statue of Pocahontas in Jamestown, Virginia), evidently was influenced by the Peale and Jarvis paintings. It stands under the watchful eyes of small sculptures of a grizzly bear and a bison.

For Further Reading

Ellen G. Miles, Saint-Mémin and the Neoclassical Profile Portrait in America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994).

Notes

| ↑1 | See “Federal Profiles, Saint-Mémin in America,” at http://www.educate.si.edu/migrations/portrait/npg.html |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul R. Cutright, “Lewis & Clark: Portraits and Portraitists,” Montana, Magazine of Western History, XIX, 2 (April 1969), 39. |

| ↑3 | William E. Foley, Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), Chapter Eight, “Mr. Governor.” |