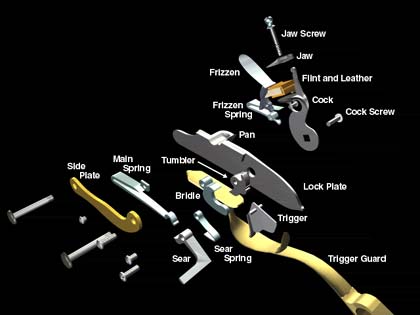

The Lock—Exploded View

Animation by BOBfx Digital Imaging

Production by David E. Nelson

Inside the Lock

As you can see in the transparent view of the lock, there are many moving parts, so regular cleaning and lubrication is essential in order to minimize friction and prevent rust and wear.

Even under the best of conditions, and with the most meticulous care, flintlock weapons misfired about one out of seven times. Rain, freezing temperatures, wind, high humidity, a worn part, a bit of rust, or a loose screw could reduce reliability to a very low margin. On the morning of 16 September 1805, Clark’s gun misfired seven times in succession as he tried to shoot a deer. That may have been because, as he soon discovered, the flint was loose, but also, snow was falling, and the lock could have been wet.

Army regulations, as well as common sense, required every soldier to carry a plug for the end of the gun barrel to keep out rain, snow, mud, and dirt. A hunter closing in for the kill with his rifle loaded and ready to fire had to remember to remove the plug before firing.

Back at Travelers’ Rest in early July 1806, Clark noted that two of the rifles had burst near the muzzle. Either a couple of men forgot to remove their barrel plugs, or else they failed to use them at all and got mud or other debris in their barrels. In either case the mistake was inexcusable.

Another essential accessory for every soldier or hunter was a piece of leather to cover the lock in wet or snowy conditions. Often cut from the knee of a cow, and thus pre-shaped to suit the purpose, it was called—what else?—a “cow’s knee.” On a rainy day in June 1805 Joseph Field nearly yielded his life to a grizzly bear because his gun was too wet to fire. Either Fields was uncharacteristically careless, or else the safeguards weren’t failsafe.

Despite numerous “improvements” in firearm manufacture since the time of Lewis and Clark, the same old problems have continued to plague soldiers periodically. In Vietnam the new and purportedly self-cleaning M16 rifles instead quickly jammed with hardened carbon deposits and became useless. The whole thing led to a Congressional Inquiry. The Model 1803 Harpers Ferry flintlock rifle might have been more reliable than the M16.

Firing Lock 1

Animation by BOBfx Digital Imaging

Production by David E. Nelson

Firing Lock 2

Animation by BOBfx Digital Imaging

Production by David E. Nelson

Best Practices in the Field

Interchangeable Parts

By the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition the flintlock firearm had been evolving over a period of 300 years. It was still literally manu-factured—hand made—and it was the most intricate mechanism an average person was apt to encounter during his lifetime, other than a clock. One more step remained—the interchangeability of parts.

In France in 1786, Thomas Jefferson saw that step being applied to the manufacture of locks for muskets. The “inventor,” said Jefferson, “presented me the parts of 50 locks, taken to pieces, and arranged in compartments. I put several together, taking the pieces at hazard as they came to hand, and found them fit interchangeably in the most perfect manner.”[1]Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (9 vols., Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1954), Vol. 9, p. 214.

It seems certain that Lewis saw to it, in person, that this very principle was applied to the manufacture of the thirty locks he ordered at Harpers Ferry, for on 20 March 1806, he noted:

The guns of Drewyer and Sergt. Pryor were both out of order. the first was repared with a new lock, the old one having become unfit for uce; the second had the cock screw broken which was replaced by a duplicate which had been prepared for the lock at Harpers ferry where she was manufactured. but for the precaution taken in bring on those extra locks, and parts of locks, in addition to the ingenuity of John Shields, most of our guns would at this moment been untirely unfit for use; but fortunately for us I have it in my power here to record that they are all in good order.[2]Elliott Coues substituted the words “broken tumbler” for Lewis’s “cock screw broken.” Coues may have surmised that the cock screw broke off at the face of the tumbler, … Continue reading

The principle of uniformity in firearm manufacture was officially adopted by the U.S. Government in 1815, but wasn’t broadly applied until the 1840’s.

Demonstration by Scott Eckberg,

courtesy U.S. Department of Interior,

National Park Service

Steps in Loading and Firing

Loading and Firing

The steps involved in loading and firing a flintlock rifle:

- Remove the ramrod from beneath the barrel.

- Pour 70 grains (a teaspoon full) of black rifle powder in the barrel.

- Place a patch of linen or leather over muzzle. The patch engages the rifling, or grooves, in the barrel, and serves as a gas seal, which increases the velocity of the bullet. It also wipes the barrel clean as it is expelled.

- Place a ball on the patch.

- Drive the ball and patch into the barrel with the ramrod, all the way to the powder in the breech, then return the ramrod to its holder under the barrel.

- Place the lock on half-cock, with the frizzen sprung forward, and pour a fine glazed priming powder into the pan.

- Close the frizzen to hold the powder in the pan.

- Pull the cock back to firing position—to “full cock.”

- Squeeze the trigger, releasing the cock.

The flint strikes the frizzen, flipping it open. A shower of sparks ignites the powder in the pan. Flame shoots through the touch-hole, igniting the powder in the breech, which expels the bullet. Including time for “springing the rod” to verify that the barrel is empty, plus cleaning the touch-hole with a pick, the whole process takes 30 to 40 seconds. Clearly, a good hunter had to be able to carry out most of the process by instinct—by the feel of it.

References

- Carl P. Russell, Firearms, Traps, and Tools of the Mountain Men (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1967), 37-43.

- George Markham, Guns of the Elite: Special Forces Firearms, 1940 to the Present (London: Arms and Armour Press, 1987), 178-179.

The author acknowledges the assistance of David E. Nelson, Technical Editor.

Notes

| ↑1 | Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (9 vols., Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1954), Vol. 9, p. 214. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Elliott Coues substituted the words “broken tumbler” for Lewis’s “cock screw broken.” Coues may have surmised that the cock screw broke off at the face of the tumbler, which would have necessitated the replacement of the tumbler. See Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition . . . (4 vols, New York: Harper, 1893; Reprint, 3 vols, New York: Dover), 3:817. |