Ancient Travelers

Looking eastward from the old trail, K’useyneiskit, toward the upper Lochsa River basin and the eastern summits of the broad Bitterroot range.

Imagine a time before airplanes, cars, or trains. Imagine a time even further back when there were no horses to ride. All travel was on foot. This ancient time was the beginning of travel across the rugged Bitterroot Mountains for the Indian tribes of the northwest United States. This is a story of travel in those mountains from ancient times up to the present.

Few people today have had the experience of bushwhacking the fifty to one-hundred, or more, miles it takes to travel between major river valleys in these Bitterroot Mountains. Travel was very strenuous in many places. Heavy brush and timber downfalls often blocked the way in summer and snow blocked the way in winter. It was virtually impossible to travel alongside creeks and rivers as modern highways now do because of the heavy brush and steep slopes. Travel was difficult for other reasons as well. You might meet up with someone from an enemy tribe. You might also meet a grizzly bear or a mountain lion in search of an easy meal—you!

In spite of these hardships, the ancient people coped. They traveled the backbones of the extensive ridge systems using game trails where possible and natural openings when available. In early spring and late fall, they followed trails located on ridge shoulders with southern exposures, taking advantage of land melted free of snow by a vigorous sun. The melting and refreezing cycle of late spring also produced a snow pack so hard that a person could walk over snow several feet deep and barely sink in. Where the terrain afforded the opportunity, the people established trails on southern slopes at lower elevations to avoid the heaviest of snows. These ancient people also learned to set the ridge tops on fire in order to clear the brush, which kept the smaller trees thinned and greatly increased the viewing distance. This was a great help because travel became less strenuous and they could see greater distances to avoid potential enemy or animal attack.

Looking westward at the original trail east of Lolo Pass. This flat area does not hold a tread very long, but it was used so heavily and so long by travelers—and later by cattle and sheep—that the swale still remains open and park-like today. It is now frequented mostly by deer and elk.

The “roads” used by those first travelers were not the well-beaten traces we think of as trails today. Instead, they were faint paths of broken brush and twigs that were hard to follow without an expert guide. Knowledge of their methods of marking trails is lost to us except for remnants of rock cairns that can still be seen, although we do not know for sure that cairns were widely used as trail markers except during the past few hundred years.

Foot trail locations were pretty much like the trails of today—they stayed on the backbones of the ridges and followed the system of ridges and saddles from major valley to major valley. Evidence of these trails no longer exists because they were so seldom used and did not scar the land. On many of the routes, we suspect that the old foot paths were obliterated by the eroded traces of horses.

Trail locations were pioneered in ancient times much as wagon roads were pioneered during the settlement rushes of the Oregon and Mormon Trails. Someone would establish an “acceptable” trail between two points and others would start using it. Then, other people would explore the area for a somewhat better route and the old route would be abandoned. In this evolutionary way, the best routes were soon established through use over the centuries.

What about “beasts of burden?” Before horses, they were people and dogs. This made long distance travel very risky and time consuming. Only the barest of essentials could be packed across these mountains; carrying enough food for long journeys was out of the question. The only alternatives were totally living off the land or visiting other tribes where friendly relationships assured food and other amenities. In the river valleys and plains, semipermanent dwellings could be used over a period of many years. These supported migration from colder to warmer elevations as the food sources and seasons changed.

Horse Trails

In the early 1700s, evolutionary changes in travel gave way to a major revolution when horses generally became available to the northwest tribes. It cannot be emphasized enough how dramatically the horse altered both transportation history and tribal culture. By the time Lewis and Clark came through the Bitterroot Mountains in 1805-06, the changes caused by horses were well established. It was now possible to travel great distances with enough food, shelter, and weaponry to make the journey as safe as it could be during those times. Food sources which were impractical before the horse now became routinely available. For example, horses enabled the hunting of buffalo over distances of hundreds of miles. The buffalo became a major food source in addition to providing robes, lodges, and bone tools, as well as many minor conveniences and personal adornments.

Horses facilitated both wider trade opportunities over much larger distances and the development of friendships with other, more distant, tribes. Trade routes were eventually established that made it possible for goods to travel hundreds of miles and change hands among several tribes between source and destination. For example, the Nez Perce of the Clearwater River established both trade and friendships with the Salish of the Bitterroot Valley and the Crows of the Yellowstone Valley.

The horse changed individual family life as well. The shorter travel times made practical the establishment of marriages and alliances between members of tribes separated by several hundred miles. Before the horse, travel on foot had limited the mobility of families and larger groups. With horses, great distances could be traveled with relatively good speed and safety. It is entirely understandable that Lewis and Clark observed that families greatly valued their horse herds.

However, the horse also brought more widespread warfare among northwest tribes. Raiding and horse stealing became part of a young man’s initiation into adulthood and preparation for chieftainhood in many tribes. We see the beginning of “war trails” extending all the way from North Dakota to Idaho and Washington. It was this stage in the evolution of tribal culture that was witnessed by European explorers during their first contacts with the northwest tribes.

Another change brought about by the horse was a revolution in the nature of the trails across the Bitterroot Mountains. Trails traveled by horses needed to be fundamentally different from those for foot traffic. This often meant a location change for better safety and navigability. Horse trails also needed to pass by the water and food sources necessary to sustain the horses over long journeys.

The physical characteristics of the trails also changed. Where soft feet once traveled with hardly a trace of their passage, the sharp, heavy hooves of horses cut into the soil, creating an ever deepening and widening erosion trace that can still be found today—more than two hundred years later. For example, the Northern Nez Perce Trail along the Lolo Trail route is still more than two feet deep in several places.

The Northern Nez Perce Trail was the old horse trail followed by Lewis and Clark in 1805-06. By that time, it had been used for decades and was deeply eroded in the steeper locations. Lewis and Clark referred to it as the “great road” in the journals because of its importance to travelers of that time. This was the original Lolo Trail. Besides all of these differences, horse trail locations had some things in common with the early foot paths. They still followed the extensive ridge systems across the mountains and they were still located on the ridge tops and ridge shoulders with snow melting southern exposures. Also, the ridges still needed to be burned for easier and more secure travel.

Wagon Roads

Matt Battani, Steve Russell’s survey assistant, stands in the tread of the original trail on Jim Brown Ridge, east of Weippe Prairie. This section of the old trail has not been used for more than 140 years.

The next fundamental change in transportation came with the introduction of wagons drawn by mules, oxen, horses, and even cattle. Euro-Americans migrating westward needed to transport goods much heaver and larger than could be carried by horses or mules. However, wagons didn’t have the huge impact on tribal culture that the horse had created, for tribal peoples had no need to transport large, heavy goods. Especially in the Bitterroot Mountains, wagon roads were difficult to build and most travelers of all cultures still transported goods on pack trains made up of horses and mules.

In the 1860s, the federal government started an extensive program of wagon road development to support westward expansion. In the northwest, the Mullan Military Road and the Lewiston and Virginia City Wagon Road were two examples. The Mullan Road went westward from Fort Benton, Montana to Helena, then down the Little Blackfoot and Clark Fork Rivers to Missoula, Montana. From Missoula, it went westward up the St. Regis de Borgia River and over the pass into Mullan and Kellogg, Idaho. Passing by Spokane and then heading south, its final destination was Fort Walla Walla, Washington. At the time, it was thought that the Mullan Road would experience frequent wagon traffic but that never happened. Long winter seasons of heavy snows, swampy conditions in the spring, and frequent bridge washouts at high water created a very short and unpredictable travel season. The potential envisioned by the federal government was never fully realized.

The Bird-Truax Trail

Even less productive was the federal plan initiated in 1865 to build a wagon road across the Bitterroot Range to carry supplies from Lewiston, Idaho Territory, to the gold fields of Montana Territory, with Virginia City as its eastern terminus, and to ship gold out. Early in 1866, Wellington Bird, a civil engineer from Mount Pleasant, Iowa, was appointed superintendent and disbursing agent for the project.

Bird recruited several other Iowans to join him, contracted with George Nicholson, a young civil engineer from Cincinnati, Ohio, for the instrument survey of the route, and engaged Oliver Marcy of Evanston, Illinois, to take charge of the earth-science aspects. Bird and his party left New York by steamer on 10 March 1866, arrived in San Francisco via Cape Horn on 5 April, and proceeded overland through Walla Walla, Washington, to Lewiston, Idaho, on the Snake River opposite the mouth of the Clearwater. At Lewiston, Bird purchased more supplies and equipment, as well as horses and mules. He also made arrangements for the additional laborers that would be needed.

On 24 May 1866 Bird and a small party headed eastward for a reconnaissance of the northern and southern Nez Perce trails. They had heard arguments in Lewiston that supported each trail as the “best” route, so they needed to make a first-hand comparison of the two. On 28 May Bird was at Schultz Ferry on the Clearwater near the settlement of Greer. His party included William Craig, Sewell Truax, George Nicholson, Oliver Marcy, and a Nez Perce guide, Tah-Tu-Tash. Craig represented the citizens of Lewiston and also served as a guide. Truax was an experienced builder of wagon roads who also was familiar with the Bitterroot Mountains.

On 9 June they were encamped at Musselshell Meadows, about 12 miles east of Weippe. The weather was so cold and rainy, and the previous winter’s snows still so deep, that they could progress no further. It was not until 26 June that the party was able to leave Musselshell and proceed eastward over the old trail, arriving in the Bitterroot Valley on 7 July. From there, the main party returned to Lewiston while Nicholson, Truax, and Tah-Tu-Tash went up the Bitterroot River to the head of the valley and then explored the southern Nez Perce trail. Nicholson was soon convinced that the northern route would be the best.

Bird learned of Nocholson’s advice on 23 July, and immediately sent laborers and supplies over the Pierce City Wagon Road to the Weippe Prairie, to begin construction, while Nicholson and his crew went ahead to conduct the instrument survey. The dense forest and the rugged terrain proved to be serious obstacles to progress. Nicholson and his crew had to shout to each other and hack through the dense brush merely to shoot their bearings. Truax followed with the laborers, who removed trees and brush to clear a bed wide enough for the wagon road. Work continued until the end of September, when the weather turned bad, and the project had to be halted until the following summer. They had cleared the timber and brush as far as Lolo Pass, yet little if any excavation or grading had been done, and no bridges had been built. Bird notified his superiors in Washington that additional funding would be necessary.

Bird wanted to return to Iowa and his family, so he made arrangements for Truax to take over as superintendent. However, this met with stern disapproval from Washington, and Truax was not approved for the job. Bird was severely criticized for leaving his post; some of the men even accused him of issuing fraudulent pay and equipment vouchers, although government records do not indicate any resolution of those issues. At any rate, federal funds were not available—even to improve the existing wagon road between Lewiston and the Nez Perce Reservation headquarters at Lapwai.

In 1877 the route that Bird’s crews had surveyed and cleared was used by the Non-Treaty Nez Perce bands for their ill-fated flight toward freedom east of the Rockies, but thereafter, traffic quickly declined, and the forest soon reclaimed it. In the early 1900s the U.S. Forest Service re-worked the 1866 trail for use by firefighting crews. In 1934 a single lane road for motorized vehicles was built over parts of the route, becoming known variously as the Lolo Divide Road, the Lolo Trail Road, or the Lolo Motorway. Meanwhile, some historically-minded people began calling the abandoned remnants of the intended Lewiston and Virginia City Wagon Road the “Bird-Truax Trail.” Today, some 40 miles of it have been designated by the Clearwater National Forest as a recreation trail for use by hikers and horseback riders.[1]Steve F. Russell, “Virginia City and Lewiston Wagon Road: Microfilm Records 1865-1870,” Ames, Iowa: Historic Trail Press, 2001, 3-4.

Railroads

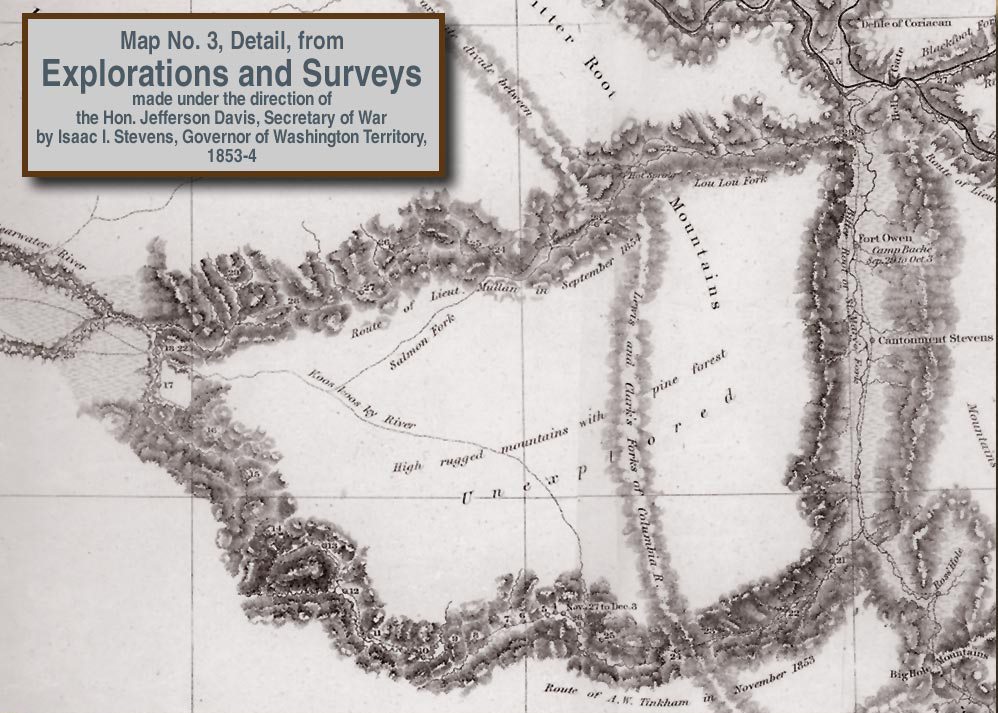

Into this mix of wagon roads and pack trails came the railroad builders. Their quest was to bring heavy-duty, long-haul transportation to every inhabitable area of the United States. The Bitterroots and the Lolo Trail were no exception. Railroad surveys were started in 1854 with the travel of Captain John Mullan over the Lolo Trail as part of his work for the Pacific Railroad surveys under the command of Isaac Stevens. What Mullan did could hardly be called a survey. He followed the Lolo Trail as fast as possible, recording infrequent, and somewhat inaccurate, notes of the route. This was quite uncharacteristic of Mullan, who was a skilled and meticulous survey engineer. It’s probably just an indication of how hopeless the route actually was.

The next railroad building efforts occurred in the early 1900s with a survey of a route up Lolo Creek, Montana and down the Lochsa River to Kooskia, Idaho. This route was highly impractical, as the Lolo Trail had been, but the railroad companies were looking to claim alternate sections of government land containing timber and minerals, which was given to companies in return for increasing access for homesteaders in the plains and valleys. The railroad was never built over Lolo Pass, but the Northern Pacific Railroad gained ownership of the land anyway, which accounts for the checkerboard ownership that is reflected in the pattern of logged-over land on both sides of Lolo Pass (see Landsat Over Lolo Pass.)

Forest Service Trails

Between 1907 and 1945, the Forest Service created an extensive system of trails to give fire control access to the region. This was really the golden age of the developed horse trail. Whereas the Nez Perce had limited their trail system to a few essential routes, the Forest Service needed access to all places within the national forest. They added extensively to the Nez Perce trail system and reconstructed many Nez Perce trails to make them safer for pack strings. An extensive system of fire lookouts was constructed on many of the highest peaks and pack trains traveled the trail system providing supplies to these lookouts. Starting in the 1930s, these trails were abandoned in favor of the easily-built one-lane roads still used today.

The Lolo Motor Way

Trail abandonment accelerated after the completion of the Lolo Divide Road, now known as the Lolo Motorway. The ancient Road to the Buffalo of the Nez Perce had been abandoned in 1866 with the completion of the Bird-Truax Trail. Now it was the Bird-Truax Trail’s turn to be abandoned after the completion of the Lolo Motorway in 1934. The abandonment of all but essential recreation access trails accelerated with hastened road building and the extensive use of helicopters and fixed wing aircraft to fight fires. After 1934, the Lolo Motorway, and trails extending north and south from it into the North Fork and Lochsa River drainages, became the major transportation access into the region. The largest users were big game hunters and outfitters. They still maintain many segments of the old Nez Perce and Forest Service trails and some of these hunter trails are very well worn.

The first automobile road on the east end led only as far as Lolo Hot Springs. The major road-building explosion came after the turn of the 20th century, when the Forest Service needed access roads for fire suppression and timber harvest. These roads were to replace the old trail system in many areas. The ease with which one-lane dirt roads could be constructed got a big boost with the invention of the bulldozer in the 1920s. This tracked vehicle with a blade on the front could be used to build roads at a furious pace compared with older methods using only hand tools.

The first road completed along the approximate route of Lewis and Clark was the Lolo Motorway, finally making a reality out of President Jefferson’s vision of a “portage” for the Lewis and Clark route. Additional Forest Service roads were built off this mainline road to access lookout sites and administrative sites.

The road system of the 1930s remained quite static along the Lolo Trail until disease started attacking the forest. The extensive logging road system on the west end was spurred along by the devastation of the White Pine with blister rust and the demand for timber in the housing boom following World War II. An equivalent road system on the east end began after the invasion of the Spruce bud worm necessitated the harvest of vast areas of timber along the Lochsa and North Fork branches of the Clearwater River. These road systems made the older trail systems obsolete except for occasional hunter use.

Today’s Trail

Today, the ancient Nez Perce trail, abandoned and largely forgotten, still winds its way along the ridges and through the saddles of the Bitterroot Mountains. Its historic erosion trace is seldom used now except by the occasional hunter or game animal. A few short segments have eroded away but most are just brush-choked. It can still be found throughout most of its entire 93-mile length.

We now honor this great road with the designation of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. In 2002 and 2003, the Idaho State Historical Society, with the help of a Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Assistance Grant, conducted a precision GPS survey of this trail. The Idaho State Historic Preservation Office has a GIS database of the trail location to within 1-2 meters. This work documents the exact location of the historic trail for future generations.

The Bird-Truax Trail has been designated as the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and about forty miles of it is now opened and being managed as a recreation trail. In several locations, the Bird-Truax and ancient Nez Perce trails are co-located and the forest visitor can enjoy hiking or horseback riding on the exact trail tread used by ancient people and famous explorers of the past.

The completion of Highway 12 in 1960 was the last major chapter in the transportation history of the Lolo Trail. Today, modern vehicles take an afternoon to travel the same distance that the Corps of Discovery traveled in several days. Days of privation and subsistence on roots and bear grease have given way to luxurious travel in motor homes and consumption of snack foods and bottled drinks.

In the twenty-first century, recreation interests and preservation interests will compete, creating issues that play a major role in the management of these historic trails.Opening them and managing them to modern standards would destroy their historic nature, and yet some opening and management needs to be done so the public can have access to them and have a quality historical experience on public land. This is an issue that is still being debated.

William Clark had sighed with relief after reaching Travelers’ Rest on 30 June 1806:

leaving those tremendious mountanes behind us—in passing of which we have experiensed Cold and hunger of which I shall ever remember.

Forty-seven years later, in September 1853, Lieutenant John Mullan, on assignment from the commander of the Railroad Survey expedition, made it from the mouth of Lolo Creek to the Nez Perce Indian village on the Clearwater near today’s Kamiah, Idaho, in just nine days. “The route had been represented to me by some to be very rugged and difficult, and by others as feasible and practicable.” His conclusion was unequivocal: “the route is thoroughly and utterly impracticable for a railroad route.” Mullan concluded:

From the head of Lo-Lo’s fork [of the Bitterroot River] to the Clearwater the country is one immense bed of rugged, difficult, pine-clad mountains, that can never be converted to any purpose for the use of man . . . . I have never met with a more uninviting or rugged bed of mountains.

On 20 June 1806, reflecting on the alternative to retracing their steps across the northern Nez Perce trail, Meriwether Lewis recalled:

From the information of the Chopunnish [Nez Perce] there is a passage which at this season of the year is not obstructed by snow, though the round [route?] is very distant and would require at least a month in its performance. The Shoshones informed us when we first met with them that there was a passage across the mountains in that quarter, but represented the difficulties arising from steep, high and rugged mountains, and also an extensive and barren plain which was to be passed without game, as infinitely more difficult than the route by which we came.

A. W. Tinkham, a civil engineer with Isaac Stevens’s railroad explorations and surveys, traveled the so-called southern Nez Perce trail between 21 November 21 and 24 December 1853, proved that it was not a practicable route for a railroad, and confirmed the reports Lewis and Clark had gotten from Indian informants.

—Joseph Mussulman

Notes

| ↑1 | Steve F. Russell, “Virginia City and Lewiston Wagon Road: Microfilm Records 1865-1870,” Ames, Iowa: Historic Trail Press, 2001, 3-4. |

|---|