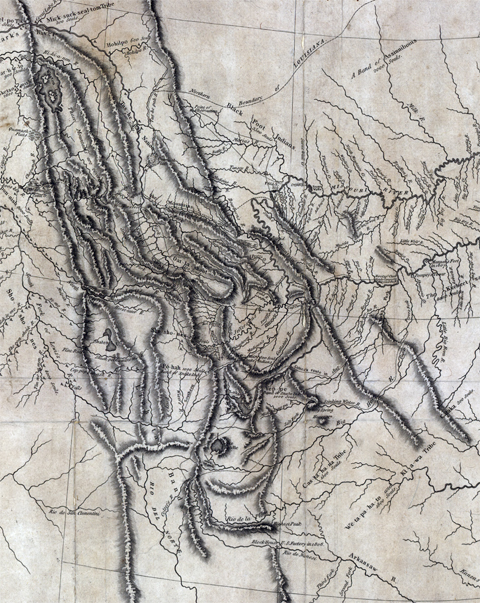

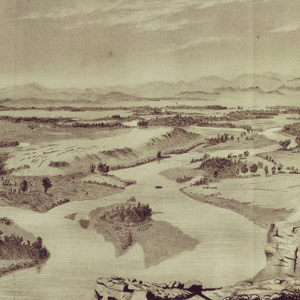

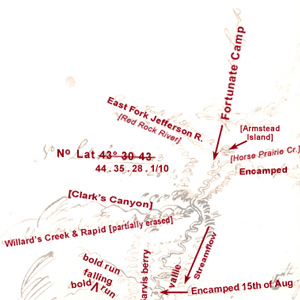

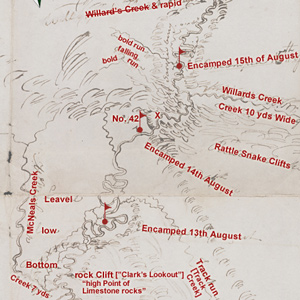

Clark’s Gates of the Rocky Mountains (1814)

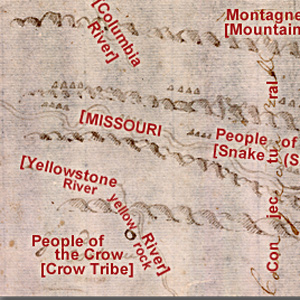

To see labels, point to the map.

American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

As the Missouri River flows south along the eastern edges of the Rocky Mountains, Clark lists each river constriction as a gate, gap, or narrows. Throughout this course, the river forks two times with each fork one-third the size than previous. The men are encouraged when Sacagawea starts seeing familiar landmarks. Scouting ahead, Lewis crosses the Continental Divide and meets the Lemhi Shoshones. Meanwhile, Clark and the boats reach the end of the navigable river.

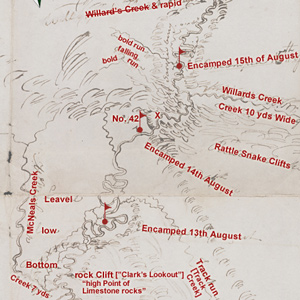

| Clark’s description | Date | Present-day name | |

| 1. | Rockey Mountains at Pine Island rapid | 16 July 1805 | Tower Rock |

| 2. | Great Gate of the Rock Mouts. | 19 July 1805 | Gates of the Mountains |

| 3. | Little Gate of the Mountain | 25 July 1805 | Toston Dam, Lombard |

| – | three forks of Missouri | 27 July 1805 | Three Forks, Headwaters of the Missouri |

| 4. | Narrows of the 3d Mountain | 1 August 1805 | Jefferson Canyon |

| 5. | 4th Gap of the Mountain | 15 August 1805 | Rattlesnake Cliffs |

| 6. | Rapid at the narrows of 5th Mtn. | 16 August 1805 | Beaverhead Canyon Gateway |

Related Pages

Clark evidently began compiling a map of the Northern Rockies after meeting with Hugh Heney at Fort Mandan on 18 December 1804, and continued adding information acquired from other traders, as well as from Indians. The reality, he would find, was much different.

The captains were worried. The expedition was quickly running out of time and space: time to cross the Rockies before winter, and space to find the Shoshones, with their horses and guides. Another month of increasingly toilsome river travel would ensue.

July 15, 1805

Leaving the Falls of the Missouri

The expedition finally leaves the Great Falls of the Missouri. They make about twenty-six river miles passing the Smith River, Square Butte, and blooming prickly pears. Lewis’s dog Seaman helps kill a deer.

“at this place there is a large rock of 400 feet high wich stands immediately in the gap which the missouri makes on it’s passage from the mountains.”

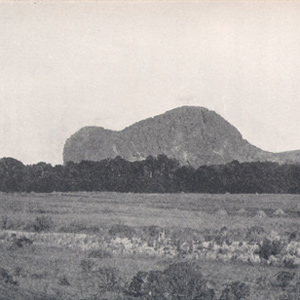

On 19 July 1805, Lewis ‘doubled’ around Oxbow Bend, then 30 feet lower and maybe one-fourth as wide as it is today. Behind the river’s curve, an ancient landmark on the Indian Old North Trail, still stands out.

The Bears Tooth was an important landmark on the the ancient Indian road that has come to be known as the Old North Trail. It was included on Nicholas King’s 1804 map, and the captains expected to find it.

July 18, 1805

Clark seeks the Shoshone

Clark, York, and privates J. Field, and Potts follow a well-traveled Indian road trying to find Shoshones. Lewis and the boats pass the Dearborn River, and he comments on blue flax and cottonwood trees.

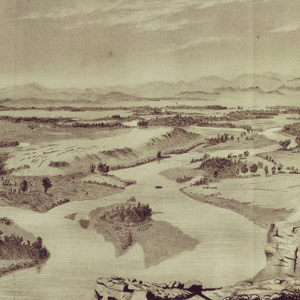

Late in the day on 19 July 1805, Lewis and his party entered a canyon between “the most remarkable clifts that we have yet seen.” They seemed to rise “from the waters edge on either side perpendicularly to the hight of 1200 feet.”

July 24, 1805

Turned side upwards

Scouting ahead, Clark sees hills “fallen half down & turned Side up-wards”. The boats pass the Crimson Bluffs, Sacagawea assures Lewis the river will remain navigable, and they camp at Yorks Islands.

Lewis and his canoes slowly approached the forks, “the current still so rapid that the men are in a continual state of their utmost exertion to get on, and they begin to weaken fast from this continual state of violent exertion.” He described the “extensive and beatifull plains and meadows.”

Before arriving at the three forks of the Missouri, Whitehouse wrote that they “passed some rough rockey hills, which we expect from the account we have from the Indian Woman that is with us, to be the commencement of the Second chain of the Rockey Mountains.

July 25, 1805

End of the Missouri

Early in the day, Clark reaches the headwaters of the Missouri. Lewis is behind with the dugouts. He describes the speed of pronghorns, and Clark explores what they would later name the Jefferson River.

July 28, 1805

Sacagawea's capture

At the headwaters of the Missouri, the expedition takes a rest day. The captains learn of Sacagawea‘s capture as a young child, and Lewis remarks on how she “would be perfectly content anywhere”.

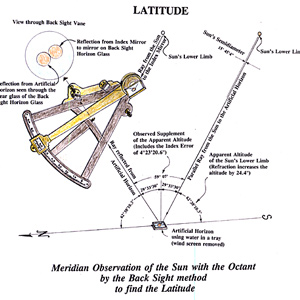

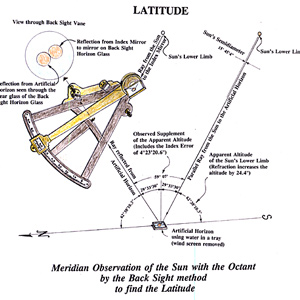

On 28 July 1805, while a fever-ridden Clark drew maps, Lewis began his celestial observations. By late night on 29 July, Lewis had completed ten discrete celestial observations consisting of a total of forty-eight separate angular measurements.

July 30, 1805

Up the Jefferson

The expedition leaves the headwaters of the Missouri, and on the Jefferson River, they pass the place of Sacagawea‘s childhood capture. Lewis scouts ahead and mires in swamps and brush.

On 1 August 1805, Clark and the expedition’s flotilla of eight dugout canoes pushed up the Jefferson River through “a verrey high mountain which jutted its tremendious Clifts on either Side for 9 Miles, the rocks ragide.” They emerged into a “wide exte[n]sive vallie.”

“We proceeded on and passed a large beautiful bottom,” wrote Pvt. Joseph Whitehouse on 2 August 1805, “and Prairies lying on both sides of the River.” On each side of the valley, Sergeant Gass observed, “there is a high range of mountains . . . with some spots of snow on their tops.”

August 6, 1805

Down the Big Hole

Forks of the Jefferson, MT Lewis sends Drouillard to tell Clark that he is on the wrong river. In going down the Big Hole, Joseph Whitehouse is nearly crushed by a canoe. Everyone, except Shannon, camp opposite the mouth of the Big Hole to dry items and recover.

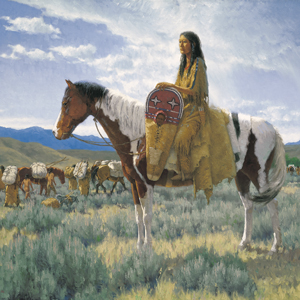

“The Indian woman recognized the point of a high plain to our right . . . . This hill she says her nation calls the beaver’s head from a conceived resemblance of its figure to the head of that animal.”

Today the confluence of the Beaverhead River and Horse Prairie Creek is submerged at left of the large island (photo center) in Clark Canyon reservoir, beneath eighty feet of water when the reservoir is full.

Lewis: “here I halted and examined those streams and readily discovered from their size that it would be vain to attempt the navigation of either any further.”

Below the summit of today’s Lemhi Pass, Lewis said that he had reached “the most distant fountain of the waters of the mighty Missouri in surch of which we have spent so many toilsome days and wristless nights.”

August 12, 1805

Across the divide

Lemhi Pass and Clark’s Lookout, MT Lewis’s small detachment crosses the Continental Divide following a good Indian trail and enters present-day Idaho. The men in the main party complain to Clark about the near-impossible task of dragging the heavy dugout canoes up the shallow and rapid Beaverhead River.

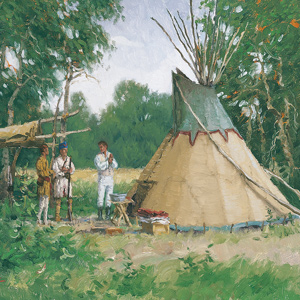

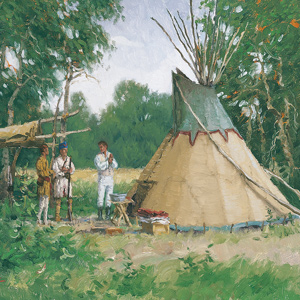

Clark’s Lookout

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark arrived at this “high Point of Limestone rocks” and strolled to its low summit. This was a convenient place from which to take at least three different bearings, making of it a surveyor’s “station” or triangulation point.

August 13, 1805

Shoshone diplomacy

Shoshone Village, ID and Clark’s Lookout, MT In the Lemhi River valley, Shoshone diplomacy includes greetings, a flag presentation, a pipe ceremony, and revelry late into the night. Back on the Beaverhead River, Clark takes bearings from Clark’s Lookout, and several men fish.

This is the landmark that white settlers believed Sacagawea really meant to identify as Beaverhead Rock . . . .

Lewis’s simple, orderly concept of the Rocky Mountains began to crumble. The truth was, this was not the easy portage to the Pacific Ocean they had expected from the beginning. Countless “chains” of mountains still intervened.

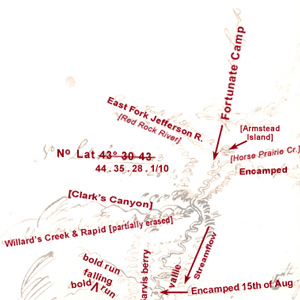

August 17, 1805

Fortunate Camp reunions

Fortunate Camp, MT Clark brings the dugout canoes up the Beaverhead River and meets Lewis and the Lemhi Shoshone Indians at what they would later call Fortunate Camp. Sacagawea is reunited with old friends and family, and negotiations for horses commences.

If, as suggested, Fortunate Camp was at 44°59’36″N, how did Lewis, after averaging four observations, come up with a latitude 24 minutes too far south?

August 24, 1805

Leaving Fortunate Camp

Salmon River, ID and Shoshone Cove, MT Lewis barters for three horses and a mule, and Charbonneau buys a horse for Sacagawea. With the help of Shoshone women, they start carrying baggage over the continental divide. Clark considers three alternate plans for reaching the Pacific Ocean.

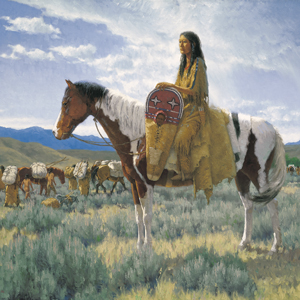

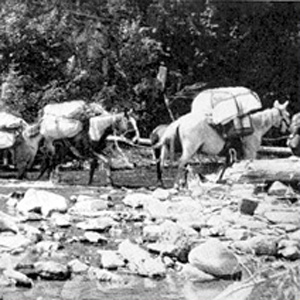

Loading and handling a packhorse is hard work. It demands not only a great deal of physical strength and endurance, but also an eye for balancing a load on the first try, a head full of horse sense, the patience of a saint, and lots of experience.

Notes

| ↑1 | From Clark’s list of “Estimated Distances.” |

|---|