Among all remaining artifacts of the expedition, this necklace of grizzly bear claws is unique (Figure 1). It is an evocative assemblage of powerful, timeless forces and historic meanings, an intersection of cultural boundaries and categories, a provocation of thought and feeling, a presence. No other expedition object invokes so many associations: the bears encountered by the party, themselves symbolic of the natural world; independent Native societies; Lewis and Clark’s interactions with Native leaders; disparate cultural framings of the natural world; the differences between the past and the present. And since the necklace is so many things—nature, culture, artifact, art, history, religion—it also raises important conceptual and methodological questions about working with historically and culturally saturated artifacts, and how they can inform our understandings of the past. The necklace could easily support an entire seminar on the expedition, viewed through the multiple lenses of anthropology, history and historiography, museum studies and material culture, Native American history, and philosophy.

Amazingly, this necklace was not known to exist until it was “rediscovered” in a Peabody Museum storeroom in late December 2003, just after the museum had launched an exhibit titled “From Nation to Nation: Reexamining Lewis and Clark’s Indian Collection.” That exhibit, as well as a simultaneously published book, Arts of Diplomacy: Lewis and Clark’s Indian Collection[fn]Castle McLaughlin, Arts of Diplomacy (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003).[/fn], presented the results of a comprehensive, multifaceted research project on the history and significance of the Peabody’s famous but poorly understood collection of Native American objects acquired by the Corps of Discovery. Since the bear claw necklace was not included in the book or in related publications, this essay presents a formal description, narrates what is known about its unusual history, summarizes the results of preliminary analysis, and suggests—but does not exhaust—some of its many meanings and provocations. Readers interested in the larger story of how the Lewis and Clark party acquired Native American objects, what happened to them after the expedition, and how those artifacts have expanded our understanding of the expedition should consult Arts of Diplomacy.

A Note About Engaging Objects

It is my hope that this essay will inspire readers to pay closer attention to artifacts as primary historical and cultural resources, because they are uniquely engaging and effective teachers (see, for example, “Coastal Woven Hats,” by Mary Malloy). Unlike text manuscripts, tangible, three-dimension objects excite our senses as well as our intellects. The materiality of historic artifacts confirms the existence of past realities and lives that were textured and embodied, and analysis of their constituent elements provides us with an opening through which to more fully explore and reconstruct the Zeitgeist of their times. Artifacts provoke questions, stir the imagination, and demand an accounting of their life histories. In the following essay about the grizzly claw necklace that Lewis and Clark conveyed to Peale’s Museum, only some of these paths are cleared.

Objects make us feel as well as think; they communicate. The bear claw necklace has a strong, palpable and venerable presence; it excites attraction while simultaneously demanding distance. Confronting these huge claws, it is impossible not to feel, viscerally, the presence of big bears, from which we all instinctively recoil. While it was on display in “From Nation to Nation,” the Peabody’s Lewis and Clark exhibit, museum visitors were drawn to it, but seldom crowded close to the case in which it rested. Some observers even reported finding it fearful. For those who understand something of its meaning and value, the impact of the necklace is especially strong. A recent visitor to the Peabody who works at a museum in Oklahoma later emailed me to say: “That bear necklace you had in the Lewis and Clark exhibit was one of the most wonderful and exciting things I’ve ever seen—sent chills up my spine. That alone was worth the ticket to Boston.”

For many Native American visitors, especially men from the western U.S., the bear claw necklace is a touchstone to a fundamental indigenous worldview that emphasizes interconnections between people, the natural world, and the spiritual realm. Few if any of our other gallery objects have resonated so strongly with Indian people, or have been so often addressed with prayers. Many Indian people have recognized a deep kinship with this necklace, and are respectfully comfortable, even inspired by being in its presence. A Native student organization in Montana has requested using an image of the necklace as their logo, noting that it represents qualities of accomplishment and leadership that they hope to encourage in their members. As a non-Indian curator and a woman, my own reaction is different: the necklace seems powerfully “other,” heightening my self-consciousness of once-profound cultural differences, including my own lack of skills for managing encounters with bears. The necklace stirs feelings of uncertainty in me that must have been familiar to members of the Corps of Discovery as the party traversed the continent.

Clearly, the necklace both emanates and preserves deep meanings that make it a cultural resource as well as an artifact of the expedition. Unlike the rest of the Lewis and Clark artifacts, the necklace is a perceptibly spiritual object, a point of mediation between life forces. While that is not the story that I tell here, it is a highly significant part of this necklace, which somehow communicates great power and mystery. Joseph Epes Brown, a perceptive student of Native American religions, addressed this quality in a passage about traditional Native “arts”:

Traditional art forms are vehicles that bear a people’s most sacred values . . . . In Native American tradition, . . . art is not the particularly created form, but the inner principle by or from which the outer form comes into being . . . . Neither beauty nor truth can manifest itself, at least in human mode, except through a being [the maker of the object] who has realized the sacred realities within himself or herself. The forms created by these people contain a unique power. Just as the spoken word or name makes present the essence or power of what is named, so too traditional art forms are experienced not just as symbols of some agreed-upon referent. A spiritual essence is present in the form.[1]Joseph Epes Brown, Animals of the Soul: Sacred Animals of the Oglala Sioux (Rockport, Massachusetts: Element Books, 1997), 84-85..

Because cultural differences are expressed in language and lexicon, it is difficult to acknowledge the many meanings of this necklace in the available vocabulary of museology and art history. While the term “bear claw necklace” has become conventional for objects of this sort, the word “necklace” implies a frivolity of adornment that has no relevance, and the word “object” sounds reductive and generalizing. In their journals, Lewis and Clark referred to claw necklaces as “collars,” an antiquarian term that today carries fewer implications, and I find the term “assemblage” both more precise and less culturally laden than most modern options. But as Nelson Atkins Museum curator Gaylord Torrence remarked to me, even the term “assemblage” is too wedded to fine art discourse, since the claws, otter fur, and other materials were joined together “in the nature of a prayer.” In an effort to avoid the ruts of “bear claw necklace,” I have made use of all of these options in crafting my remarks.

Provenance

Like a hibernating bear, the grizzly claw necklace remained physically secluded and “off the record” for decades in a Peabody Museum storage room. Institutional records were unclear as to whether [or not] it had become part of the collection along with other Lewis and Clark objects that were received from the Boston Museum in 1899. When the Peabody conducted extensive research to identify those expedition related materials, the bear claw necklace could not be located. Then, suddenly, it surfaced in December 2003, immediately following the installation of a major exhibition of the Peabody Museum’s Lewis and Clark collection. Native American elders had guided the exhibit installation process by praying with, speaking to, and handling the objects and by blessing the gallery space and involved museum staff. Since human relationships with bears are everywhere propitiated by ritual, it seemed entirely fitting that the long-dormant necklace should emergence in response to this concentration of energy and activity.

The dramatic “rediscovery” of an important expedition artifact was announced in a New York Times article in early 2004, generating a swell of media attention during the early bicentennial commemoration. The discovery of unrecognized treasures in attics or museum collections is always compelling, and artifacts associated with the Lewis and Clark expedition are rare. A subsequent editorial observed that while the “point of a museum” is not only to house but to control objects, the reappearance of the necklace made it seem “all the more remarkable—as if it had come fresh from the hands of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.”[2]“Lost Gift to Lewis and Clark Is Found,” The New York Times, 21 January 2004. Editorial, “An Unexpected Artifact” The New York Times, 22 January 2004.

The magic of such “lost and found” stories is of course conjured up by prosaic factors—large collections, old, historic and/or poor records, generations of staff, changing technologies and methods for collections care and management, coupled with a lack of human and fiscal resources. When building their collections during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many institutions acquired materials with little or no provenance (known history), and collections management was in its infancy. Museums and other repositories have by and large been chronically under-staffed and under-funded, while the costs of collections management and care have sky-rocketed in recent decades. Until such work was mandated by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, prompting Harvard University to fund a temporary staff expansion, the Peabody lacked the resources necessary to conduct a thorough inventory of its extensive holdings, which total some 600,000 archaeological and ethnographic objects from around the world. Likewise, the Lewis and Clark bicentennial prompted the first comprehensive study of its well-known but poorly understood “Lewis and Clark collection,” which proved to be a considerable endeavor.[3]Castle McLaughlin, Arts of Diplomacy: Lewis and Clark’s Indian Collection (Cambridge, Massachusetts and Seattle: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and Universityof Washington Press, … Continue reading Happily, these two initiatives converged at just the right time, so that when the inventory team found this necklace, its identity was recognized.

The known history of the grizzly necklace began when it entered the crowded, eclectic halls of early America’s first major museum, established in Philadelphia by the artist and philosopher Charles Willson Peale in 1795. At various times, President Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis, and William Clark all presented Peale with Native American and natural history objects acquired on the expedition. Peale listed most of these acquisitions in his museum ledger, but the objects are described in a regrettably cursory fashion. A microfilm version of Peale’s “Memoranda of the Philadelphia Museum” (housed at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania) and the transcription of his December 1809 Lewis and Clark list reprinted by Donald Jackson[4]Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with related Documents, 1783-1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:476-79. guided our search at the Peabody for former Peale Museum materials. Not surprisingly, it soon became evident that Peale’s museum records were incomplete.

Unfortunately, the grizzly claw necklace is one of several expedition artifacts that do not appear on Peale’s 1809 list. Part of the explanation for this omission may be that Peale never entered into the ledger an account of the objects he received after the unexpected death of Meriwether Lewis, which arrived in Philadelphia with no documentation. More generally, while Peale was unusually conscientious, record keeping was not a focus during the formative era of museums, when even the largest of such institutions were generally managed by individuals and their families. Neither Peale nor the Boston Museum seem to have created numeric catalogues of their holdings, and none of their former objects now at the Peabody were physically labeled or marked in any fashion that would facilitate intellectual control.

From Peale to the Peabody

Peale did, however, create an exhibit that framed Lewis and Clark as cross-cultural diplomats among the Indians, featuring a wax figure of Lewis dressed in garments given to him by the Lemhi Shoshone leader Cameahwait and holding a calumet pipe (now lost). As documented by a floor plan of the museum circa 1820,[5]David R. Brigham, Public Culture in the Early Republic: Peale’s Museum and its Audience (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995), 108. this thematic installation kept his expedition-related objects in a discrete group, and the arrangement seems to have survived until 1848, when the contents of the museum were catalogued for a sheriff’s sale.[6]Charles Coleman Sellers, Mr. Peale’s Museum: Charles Willson Peale and the First Popular Museum of Natural Science and Art (New York: Norton, 1980), 312-16. Peale’s Lewis and Clark exhibit also apparently necessitated the creation of hand-written labels to explain the garments, pipes, and other expedition objects placed on display.

The Peale Museum closed in 1846, and by 1849, a portion of the widely-dispersed contents had been jointly purchased by P.T. Barnum and Moses Kimball, proprietor of the Boston Museum. Kimball had assembled his museum by purchasing the defunct New England Museum and other failed museum enterprises in the Boston area. Fortunately, Kimball seems to have received most of Peale’s Lewis and Clark materials, because Barnum’s several museum ventures were destroyed by fire. By 1850, there was virtually no public interest in the Lewis and Clark expedition, and the scant surviving records suggest that neither Barnum’s American Museum in New York nor the Boston Museum drew attention to related artifacts. After Moses Kimball retired in 1860, the focus of the museum shifted to theatrical performances. In 1893, the Boston Museum began transferring their natural history specimens—some of which had also belonged to Peale—to the Boston Society of Natural History. The bird specimens were sold to a society member and stored in his barn. Although later redeemed by the Society, unfortunately the birds were removed from their mounts and their labels lost before the tattered collection found refuge at Harvard’s Zoological Museum (now Museum of Natural History). Only one of those specimens, Lewis’s woodpecker, (Melanerpes lewis) has been successfully identified as an expedition artifact, and it is now regarded as priceless.

Following an 1899 gallery fire, the disenchanted Kimball heirs (several of whom were Harvard graduates) next invited the Peabody to select surviving cultural materials for the museum’s expanding teaching collections. Curator (and later director) Charles C. Willoughby chose 1441 objects from around the world, which were conveyed from Boston to Cambridge by horse-drawn wagon. Among them were many treasures from Peale’s ill-fated collections, including the famous “Feejee Mermaid,” the remnants of Lewis and Clark’s Native American materials, and George Washington’s blue watered silk sash, to name but a few. The Boston Museum collection was recorded in the Peabody’s large leather ledger book as accession 1899-12.

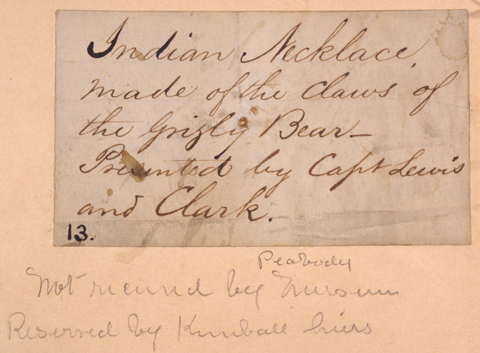

Fortunately, Willoughby also secured an assortment of original object labels, although they had become disassociated from their referents. The labels are themselves fascinating and tactile artifacts, richly resonant of nineteenth century museum cultures. Some of the labels were hand-written in cursive script with sepia ink and a dip pen, others printed in block letters on stiff, heavy paper or on the reverse side of admission tickets; two remain glued to a page marked “Aug 6, 1834.” In 1901, Mr. J.D. Sornborger of the Boston Society of Natural History hand-carried the surviving labels to Philadelphia, where they were examined by several of Peale’s grandchildren. The descendants identified the handwriting styles of Charles W. Peale and his sons Franklin and Titian, and sorted the labels accordingly. Once the labels were returned to the Peabody, Willoughby pasted many of them into a notebook, hoping to match them to objects in the newly acquired Boston Museum collection.

Among the several labels believed to have been penned by Franklin Peale (1795-1870) is the one shown above (Figure 2). At some point the penciled annotation was added: “Not received by Peabody Museum—Reserved by Kimball heirs.” Two other Peale labels also refer to grizzly claw ornaments. But Willoughby—who also relied on a transcription of Peale’s ledger to guide his research on the former Boston Museum materials—made no mention of grizzly claw objects in his 1905 article on the Peabody’s Lewis and Clark collection.[7]Charles C. Willoughby, “A Few Ethnological Specimens Collected by Lewis and Clark,” American Anthropologist, vol. 7, no. 4 (1905), 633-641.

When we began investigating the collection in 1997 we hoped that the ambiguity of this record indicated that the necklace might be in the museum, and we searched for it diligently. The only grizzly-related objects identified as a potential match for an extant Peale label were two single grizzly claws that seemed once to have been part of a necklace. The claws and the label are discussed (p. 260) in Chapter 9 of Arts of Diplomacy, which deals with objects that might have been brought back by Lewis and Clark, but lack sufficient documentation to confirm it as fact.

The 2003 Discovery

There things stood, until the necklace—carefully stored in a custom-made container—was located by two staff members while inventorying the Oceanic storeroom and who recognized it as a North American bear claw necklace. A quick check of the files revealed that it had been donated to the museum in 1941 by a female Kimball family descendant with a different married name. At that time, and for decades thereafter, the Peabody was staffed primarily by Harvard students and by volunteers.

Because the grizzly claw necklace was accepted in a group of ten objects from the Pacific Islands, which also included a fragmentary whale tooth necklace (Figure 3), it was catalogued as a “neck ornament of claws in imitation of a whale tooth necklace.” Today this seems inconceivable, but it is an interesting error. Obviously the cataloger was familiar with necklaces made from sperm whale teeth, which were important in the nineteenth century China trade because they were so highly prized by Tongan, Fijian, and Samoan chiefs. Whale tooth necklaces were made in several conventional forms, including a “saber-toothed” style in which long tooth fragments modified to resemble the teeth or claws of predators were strung in graduated lengths.[8]Fergus Clunie, Yalo I Viti; Shades of Viti: A Fiji Museum Catalogue, (Suva, Fiji: Fiji Museum, 1986), 49; Fig. 3. This basic design pattern is indeed shared by most North American bear claw necklaces. Yet the cataloguer felt something was not quite “right,” so she described it as an “imitation,” perhaps also aware that visual punning and the production of “fau”X shell and bone carvings was widely practiced in Polynesia. At any rate, after being catalogued, the necklace was housed in a supportive container and placed among the Polynesian artifacts.

We now surmise that the grizzly claw necklace did come to the Peabody as part of the initial 1899 gift, but was subsequently withdrawn when a family representative reviewed Willoughby’s choices, leaving only the Peale label in the museum archives. A generation or two later, the necklace was returned to the museum along with other former Boston Museum artifacts. According to museum correspondence files, by the 1970s few members of the Kimball family remembered that their ancestor had ever given Harvard such a large and important collection.

The Object and Artifact

Figure 4

Loose, perforated grizzly claws found with the necklace

© 2008 Harvard University, Peabody Museum 41-54-10.1; 41-54-10/99700.2; 41-54-10/9970.3.

Vermilion, a trade pigment, may be present on the claw on the left.

Despite taking a keen interest in grizzly bears and describing the men’s necklaces of grizzly claws they saw while traveling across the continent, Lewis and Clark seem to have left no written commentary regarding the cultural or geographic origins of the claw collar they deposited at Peale’s Philadelphia museum. This omission is consistent with their generally sparse documentation of the Native American materials they acquired, which were not regarded as “specimens” in the same manner as minerals or birds. They acquired most of their Native American objects in the course of diplomatic exchanges and pragmatic barter, and did provide basic information about them—sometimes including the previous owner’s name—to museum proprietor Charles Willson Peale, who entered the information in a museum ledger. Unfortunately this necklace does not appear on Peale’s museum accession list, our single best guide to the extant collection at the Peabody. Likewise, the handwritten Peale label for the necklace makes no mention of its tribal or individual origins.

Even so, we can learn both about and from this necklace. This essay presents a description of its material properties, using those characteristics as a basis for comparing the necklace to other known examples. Criterion for the classification and dating of North American bear claw necklaces that were proposed nearly fifty years ago by Norman Feder and Milford G. Chandler[9]Norman Feder and Milford G. Chandler, “Grizzly Claw Necklaces,” American Indian Tradition, vol. 8, no. 1 (1961), 7-16. support a very early date for the Peabody necklace relative to other known examples, and suggest an origin in the geopolitical region of the Upper Missouri River. Lewis and Clark’s descriptions of bear claw collars and their relationships with various tribal communities are reviewed for clues as to the tribal origin of the necklace, and it is compared to a similar necklace acquired by Prince Maximilian from the Mandan chief Mato Tope (Four Bears). Contextual ethnographic and historic data show that the bear claw collars worn by Native leaders were considered culturally appropriate gifts for chiefs to present to important visitors. Lewis and Clark established cordial diplomatic relationships with Yankton, Mandan, Nez Perce, and Shoshone chiefs, all of whom they reported as wearing bear claw necklaces. Ultimately, as we found with the rest of the Lewis and Clark collection, a specific attribution remains elusive because for early historic material culture, regional styles are much better understood than are tribal distinctions.

Yet the necklace remains a powerful statement of an ancient indigenous theology based on maintaining reciprocal relationships with both natural and with supernatural forces governing the universe. As an expression of core values as well as specific ideas about bears, the necklace highlights the cultural vitality of the independent western native nations encountered by Lewis and Clark, and serves as a touchstone to indigenous consciousness and philosophy. It also underscores the well-known significance of grizzlies in expedition history, and deepens our appreciation of how a shared interest in bears mediated interactions between Indian people and Lewis and Clark despite vast differences in their understanding of those animals.

Physical Description

As a form, the bear claw necklace is simple and direct. It is an assemblage of thirty-five perforated grizzly claws, lashed to a foundation of otter hide and covered with red pigment. Three additional, detached claws, two of which have a second hole drilled in the center, were found in the same storage container as the necklace (Fig. 4). While it is unclear whether they were originally associated with the necklace, only the claw with a single perforated hole would seem to be a good match. With the possible exception of vermilion (a European-made red pigment available decades before the Lewis and Clark expedition) on one of the double-perforated loose claws, no Euro American trade goods appear to have been utilized in its creation. Their absence is a striking departure from the other objects in the Lewis and Clark collection, particularly in comparison to the other Plains materials. Unlike beaded garments or woven hats, here there are no markers of chronology or social interaction. Instead, the necklace refers primarily to essential, and therefore, timeless, values and relationships.

Preliminary macroscopic analysis of the necklace was undertaken by Peabody zooarchaeologist Richard Meadow, Peabody conservator Scott Fulton, and by David Mather, a Minnesota archaeologist specializing in the cultural history of North American bears. Each of the thirty-five large claws on the necklace were taken from the forefeet of grizzlies. The claws were probably soaked to soften them before they were perforated once by working each side with a flint tool, strung on a rawhide thong, and lashed with sinew to a foundation made of river otter (Lutra canadensis) fur. The claws-which are variegated shades of ivoried yellows, olives, and browns- were also modified by cutting away part of the undersides to flatten and smooth their surfaces (Figure 5). Red ochre, a mineral pigment, covers the knuckles and the underside of the claws as well as portions of the otter fur. The otter hide has been denuded by time and insect damage, which have stripped away the long guard hairs, leaving only the dense nap of the under coat. Unfortunately, the necklace is also now missing the neck strap, an important component of stylistic and cultural information.

The necklace was carefully strung in graduated fashion, so that the longest claws fall in the center. Longest of them all at 8.7 cm, or about 3.5 inches, is a visually distinctive claw that appears to be carved from old, dark wood, but which is actually the keratin, or sheath of a claw now missing a bone core (Figure 6). It is possible that this “anomalous” claw pre-dates the others, but this seems unlikely, since bone is more durable than keratin. The remaining claws were sorted by color and size and strung across from one another in opposing pairs. Mather has determined that at least twenty individual bears are represented on the necklace, each of which contributed between one and four claws. Curvature, length, and color patterns indicate that claws from both the left and the right forepaws are included, in some cases likely representing pairs of claws from the same animal. While they look imposing, the size of these claws (between three and four inches long) is within the range of variation for contemporary grizzlies, and is consistent with the average length of claws that Lewis and Clark reported having seen on necklaces and on the feet of bears killed by members of their party. According to expedition journals, expedition members killed at least two huge grizzlies whose claws measured between six and seven inches long.

Many of the grizzlies killed by the Lewis and Clark party were closely examined and described by Meriwether Lewis because of his passionate interest in discovering how this massive, unfamiliar “white bear” fit into emerging systems of natural history classification and discourse, especially with regard to species distinctions. Paul Schullery’s Lewis and Clark Among the Grizzlies[10](Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2002), 53-54. provides a cogent account of how Lewis’s evolving analytical interest in grizzlies resulted in the earliest scientific descriptions of the bears, which many consider to be the expedition’s most notable intellectual achievement. While long-standing debates about speciation have been largely solved by genetic research, modern bear researchers believe that scientific analysis of the claws on this necklace could provide valuable information about the ecology and demography of grizzly populations in the early nineteenth century that could potentially contribute to current conservation efforts. It is possible that the claws represent the historically significant but long-extinct “Plains Grizzly,” a little understood variety or ecotype of Ursos arctos, the brown bear. Microscopic portions of the claws might also yield information about the diet, age, and geographic location of the bears from which they were taken, in turn suggesting where Lewis and Clark obtained the necklace. But given the tremendous cultural and historic significance of the necklace, sampling even miniscule portions of the claws for analysis is unlikely.

Form and Cultural Identity

The cultural origin of the necklace is of great interest to many people, but we may never know for certain who conveyed it to Jefferson’s party. No related documentation has been found, and bear claw collars such as this one were worn by men from many tribes in the region between the Upper Missouri River area and the Rocky Mountains. In the broadest sense, claw collars are one manifestation of the deep and ancient reverence that Native American people have for bears, which is strongly expressed throughout their religious ceremonies, traditional narratives, and material culture—a complex of beliefs and practices that Irving Hollowell famously termed “bear ceremonialism.”[11]Irving A. Hollowell, “Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern Hemisphere,” American Anthropologist, 28 (1926), 1-175. Bear ceremonialism was ubiquitous throughout the prehistoric northern hemisphere, and has existed in North America as long as humans have occupied the continent. Native North American peoples shared the belief that bears were close relatives of people, but that this relationship of “dangerous kinship” required ritual mediation. Since most Native communities recognized in bears two other dominant characteristics: their ferocity and tenacity of life, and their knowledge of medicinal plants and healing, they were widely seen as the patrons of warriors, shamans, and doctors. As shown in pecked and painted rock art across the continent as well as archaeological recovery of claws, the dominant symbol for bears has long been a paw with claws, representing both the aggressive bear and the digger of medicines. Ethnographer John Ewers observed that when eastern Woodlands peoples moved west onto the Plains and encountered grizzlies, their bear ceremonialism intensified.[12]John Ewers, “The Bear Cult Among the Assiniboins and their Neighbors,” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, vol. 11, no. 1, 131-145.

Real claws were not considered to be mere symbols, but rather, potent, metonymic links to a living, spiritual essence of tremendous force. If cared for properly, they would strengthen a man’s relationship with those powers, enabling him to do great things under their protection and guidance. While reviewing much of the related ethno-historic literature, I was struck by the extent to which Indian men expressed the idea that having bear claws was more important than the manner in which they were acquired. Whether they were obtained directly by killing bears, traded for, captured, or purchased, claws were thought to have an inherent, latent power that could be activated to the benefit of the owner if handled in an appropriate ritual fashion.

Both warriors and spiritual leaders sought to cultivate relationships with bear powers, and men made such connections manifest by taking a bear name (e.g., Four Bears), mimicking bear sounds and behavior, performing relevant rituals, wearing images of bears, and attaching paws and claws to their garments, shields, and tipis. Because of the profound significance of bears in Native cultures, a full consideration of that topic and its implications for bear claw necklaces is beyond the scope of this essay. However, such an enterprise would necessarily take account of the many shared aspects of North American “bear ceremonialism”[13]Hallowell, 1-175; David Rockwell, Giving Voice to Bear: North American Indian Rituals, Myths, and Images of the Bear (Niwot, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart, 1991); Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders, The … Continue reading and related art,[14]John Ewers, “The Awesome Bear in Plains Indian Art,” American Indian Art, vol. 7, no. 3 (1982), 36-45. as well as how relationships with bears were organized in specific cultural contexts. Little attention has been paid to changes in bear ceremonialism and related material culture during the nineteenth century, but it is likely that changes in hunting technology, leadership, trade relations and other aspects of social life effected the making, use, and meaning of bear claw collars over time.

A basic research method for identifying artifacts is to undertake a formal analysis of their material properties and to compare their physical attributes and style with similar things that do have an established history, or provenance. To my knowledge, the only comparative study on grizzly claw necklaces was undertaken by Norman Feder and Milford E. Chandler, who studied museum examples in hope of identifying tribal and chronological styles. In their 1961 article “Grizzly Claw Necklaces,” the authors present four major styles based on construction methods and stylistic features.[15]Norman Feder and Milford G. Chandler, “Grizzly Claw Necklaces,” American Indian Tradition, Vol. 8, no. 1 (1961), 11. But they warned that, “Very little can be stated as absolute fact concerning the differences in necklace construction by different tribes,” due to the scarcity of examples, the wide range of forms worn by members of the same culture, and the complications of trade. For example, the range of distribution for their most basic or “Plains style” of necklace, which consists of simply strung claws, with or without added spacers such as beads, extends from the Great Lakes to the Plateau and includes a wide variety of forms.

As is often true of early examples of types or styles of things, the “Lewis and Clark” grizzly claw necklace doesn’t conform exactly to any of the Feder and Chandler categories. Instead, it is a hybrid between the ubiquitous “Plains style” and their “Style 4,” which is “characterized by claws with a double perforation mounted on a core and covered with otter fur,” which the authors found to be distributed along the Missouri River and into the western Great Lakes. The authors discriminate four distinct types, or variations, of Style 4, based on different treatments of the head and the tail of the otter. By far the most common and relevant to this discussion is their “Type 3,” or Upper Missouri River variant, which is described as having “a core that is not continuous around the back, and further uses the tail and head of the otter as decorative projections.”

Both “Upper Missouri” necklaces, which the authors associate with tribes such as the Arikaras, Pawnees, and Mandans, and “Plains style” claw collars are well documented in the early portraits of Plains Indian men painted by artists George Catlin and Karl Bodmer along the Upper Missouri in the 1830s. During that decade, new steamship service on the Missouri greatly increased communication between the “frontier” and St. Louis, entr’pot to the west. Several European and American adventurers who visited Native communities and trading posts along the river have left written and artistic documentation of lasting value. Among the most important of these frontier chroniclers were the German prince Maximilian of Wied and Bodmer, a young Swiss artist hired to illustrate their travels. After consulting with William Clark and directors of the American Fur Company in St. Louis, Maximilian and Bodmer traveled along the Upper Missouri throughout 1833-34, spending the winter among the Mandan. Maximilian observed that

The Mandans and Manitaries [Hidatsas], and all the Indians of the Upper Missouri, often wear the handsome necklace made of the claws of the grizzly bear. These claws are very large in the spring, frequently three inches long, and the points are tinged of a white colour, which is much esteemed; only the claws of the fore feet are used for necklaces, which are fastened to a strip of animal skin, lined with red cloth, and embroidered with glass beads, which hangs down the back like a long tail. Such a necklace is seldom to be had for less than twelve dollars; and very often the owners of them will not part with them on any terms.[16]Maximilian, Prince of Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, Vol. 2, in Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Early Western Travels, 1748-1846 (Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark, 1906), 24:262.

Feder and Chandler imply that the Upper Missouri style was the early prototype for the later and increasingly elaborate Prairie style developed by riverine and prairie tribes such as the Iowas, Poncas, Missourias, Sauks, and Mesquakies. However, that hypothesis may be an artifact of our limited historic record, as well as of personal bias. The chronological development implicit in their descriptions is correlated with an increasing elaboration over time of the “tail” of bear claw necklaces, culminating in the highly conventionalized prairie-style necklaces (especially Mesquakie, Figure 6) of the period 1860-1890. The “prototype” necklace of this style was collected about 1925 by Milford Chandler, co-author of the comparative study, in Tama, Iowa.

Now owned by the Detroit Institute of Arts, images of that necklace have been included in so many publications that it has become iconic of bear claw necklaces in general.[17]Art of the Great Lakes Indians, Flint Institute of Arts, Flint Michigan, 1973; David W. Penney, Art of the American Indian Frontier: the Chandler-Pohrt Collection (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, … Continue reading The authors consider necklaces of this kind (“Style 4, Type 4”) to be “the ultimate in the development of the grizzly claw necklace as an ornament,” and they are clearly very different in form and affect from the Lewis and Clark necklace.

Other Necklaces

Grizzly claw necklace commissioned from Mandan Mato Tope (Four Bears) by Maximilian, 1833-34.

Charging Eagle, son of the Mandan chief Mato-tope (also known as Four Bears), wearing a bear claw necklace.

While the historic record is too fragmentary to fully reconstruct the cultural history of bear claw necklace styles, it is apparent that otter fur war wraps and long otter tail pendants—independent of bear claws—were worn by Northern Plains men by 1800. Lewis and Clark were deeply impressed by the sight of Nez Perce and Shoshone warriors wearing elaborate otter neck drapes in 1805-1806, including otter “tippets,” which Lewis proclaimed “the most elegant piece of Indian dress I ever saw” (See Lewis’s Shoshone Tippet). More generally, Lewis said of the Shoshone: “Their ornements are Orter Skin decurated with See Shells;”[18]Moulton, Journals, 5:139. and of the Nez Perce:

Collars of bears Claws are also Common; but the article of dress on which they appear to bestow most pains and orniments is a kind of collar or breastplate; this is most commonly a Strip of otter skins of about Six inches Wide taken out of the Center of the Skin it’s whole length including the head. this is dressed with the hair on, this is tied around the neck & hangs in front of the body the tail frequently reaching below their knees; on this skin in front is attached pieces of pirl, beeds, wampum, pices of red Cloth and in Short whatever they conceive most valuable or ornamental.[19]Ibid., 7:224.

In a portrait by Karl Bodmer, the Siksika Blackfeet man The Low Horn wears a spectacular example of an otter war tippet covered with sparkling white shells and featuring a long and embellished tail.[20]Davis Thomas and Karin Rohhefeldt, ed., People of the First Man; Life Among the Plains Indians in Their Final Days of Glory (New York: Promontory Press, 1982), 141. At one time, the Peale Museum had a tippet given to Lewis by the Shoshone leader Cameawait, but it is no longer part of the surviving collection. It was probably lost in the fires that destroyed several museums owned by P.T. Barnum, who purchased some of the Peale Museum collections in 1849-1850.

According to Lewis, the Nez Perce leader Hohâstillpilp also wore a “tippet” made from the scalps and fingers of enemies he had killed in battle. Necklaces strung from multiple, graduated animal digits or other component parts alternating with spacers were common on the Plains, other examples being duck bills, turtle leg bones, raptor talons, and human fingers, which were sometimes alternated with bear claws. Such assemblages are based on the same pattern of simple stringing that defines Feder and Chandler’s “Plains style” bear claw necklaces.

The most famous surviving “Upper Missouri” necklace was acquired by Maximilian from the celebrated Mandan war chief Mato Tope or Four Bears (Figure 7) and is now in the Linden-Museum in Stuttgart.[21]“In the River of Time: Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara: Native Live Along the Upper Missouri River,” Exhibit catalog, Linden Museum, Stuttgart, 2000; Axel Schulze-Thulin, ed., Indianer der … Continue reading The Mato Tope claw collar seems to typify an Upper Missouri style of the period, when the Mandan and Hidatsa villages were important centers of trade, interaction and influence. Mato Topes’ skill at managing relationships in this cross roads of intertribal and international traffic is underscored by the use of blue glass trade beads on his necklace. Everywhere they traveled, Lewis and Clark found blue beads more highly valued than any other color, and this color of bead seems to have been important for use on early bear claw necklaces. Bodmer’s portraits of contemporary village leaders The Flying Eagle (Mandan) and Two Ravens (Hidatsa) depict those men wearing similar Upper Missouri style claw collars.[22]Thomas and Ronnefeldt, 237, 222.

Some of the published photographs of Mato Tope’s necklace, including one used by Feder and Chandler, clearly show that the “tail” of his necklace was simply the literal and unembellished hindquarters and tail of an otter. We might expect that the literal form of tail was also the earliest. If so, the style was also persistent. Many years later, Mato Tope’s son, Charging Eagle, was photographed wearing a claw necklace very similar to his father’s—but with the claws oriented up, as Lewis saw them worn among the Shoshone (Figure 8). Unfortunately, if the Peabody’s necklace ever had a “tail,” it is now missing.

Mato Tope’s necklace is smaller than the Peabody necklace, and the twenty-two grizzly claws on the Mandan example are strikingly uniform in their light yellow color, which was said to be prized on the Plains and prairie. In length, the claws are much more varied than are those on the Peabody assemblage, and the additional string of blue bead spacers creates overall a more delicate and finished appearance.[23]The Linden necklace is an especially valuable example of Mandan style because according to Maximilian, he commissioned Mato Tope to create it. In his journal entry for 24 November 1833, Maximilian … Continue reading Nonetheless, the two necklaces share both the simple otter body foundation and a minimalism that derives in part from their early nineteenth century origins. The claws on both necklaces were trimmed and shaped, which Feder and Chandler associate with the oldest known examples, and were strung in graduated pairs of like size and color, possibly representing the claws of individual bears. Unlike all other known examples of the Missouri River style, the claws of the Peabody necklace were drilled only once, and no glass trade beads were added. Since Feder and Chandler suggest that single drilling was both the oldest and most widespread practice, it seems reasonable to assume that the Lewis and Clark necklace represents an earlier version of the 1830s “Upper Missouri” style as illustrated by Mato Tope’s necklace. From the perspective of social relationships, it would make sense for Lewis and Clark to have obtained the Peabody bear claw necklace during their long and hospitable stay among the Mandan. Still, even taking into account that the Peabody necklace would have been made a generation earlier than Mato Tope’s collar, the absence of beads and other European materials seems curious, given that the Mandan and Hidatsa villages were such active centers of trade.

1830’s Styles

At the time of the expedition, grizzly claw and otter fur necklaces were worn by tribes from the Missouri River west to the Rocky Mountains. The persistence of this style throughout the nineteenth century is well documented by artists and travelers, although their reports often lack details regarding formal treatment of the head and tail of the otter.

While resting in the Mandan and Hidatsa villages en route home in August 1806, Clark called on a party of visiting Cheyenne and observed that, “they also ware Bear’s Claws about their necks, Strips of otter skin (which they as well as the ricaras are excessively fond of) around their neck falling down behind”[24]Moulton, Journals, 8:318. George Catlin depicted men from a number of Missouri River tribes wearing simple claw and otter collars without long tails during the 1830s (Figure 9).

At mid-century, the trader Edwin Denig wrote of the Assiniboine: “A good many of the renowned warriors wear necklaces made of the claws of the grizzly bear, worked or tied on a strip of otter skin,”[25]Edwin Thompson Denig, The Assiniboine (1930; repr. with a new introduction by David R. Miller, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 159. Later still, Weasel Tail, a Blood Indian from Montana, was photographed wearing a bear claw collar with an otter or beaver fur foundation.[26]John Ewers, Indian Life on the Upper Missouri (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968), Plate I.

By the 1830s if not before, Mandan and Hidatsa men were wearing several styles of bear claw necklaces. In one of Bodmer’s paintings of a Hidatsa scalp dance, a robed man wears a collar of fur and grizzly claws to which is attached a long otter tail displaying additional large claws[27]Thomas and Ronnefeldt, 215. So longer and more ornate bear claw necklaces, perhaps inspired by the Rocky Mountain tippets, were already en vogue at the time that Mato Tope created his more austere example. If these distinct necklace styles also once implied a social distinction between the men who wore them, that knowledge has not survived. According to Hidatsa men interviewed by anthropologist Alfred Bowers during the 1930s, otters, like bears, were considered to be “doctors” and were included in hereditary, personally owned grizzly bear bundles that were used for both healing and directing warfare.[28]Alfred W. Bowers, Hidatsa Social and Ceremonial Organization (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.)

The claws on both Mato Tope’s necklace and the Lewis and Clark necklace are covered with red ochre, a pigment used to express a complex of meanings including life, blood, and the presence of holy or sacred forces (according to Lewis, the Shoshone regarded it as emblematic of peace). While Feder and Chandler suggest that red-painted claws are diagnostic of “Siou”X origins, this is an error, for the use of red ochre (and later, Chinese vermilion, which Lewis purchased as a trade item) is both ubiquitous and ancient. In fact, red pigment is apparent on so many bear claw necklaces that it seems to have been requisite. Jim Hanson states that it symbolizes “the flowing blood of enemies slashed by the bear.”[29]James Hanson, Spirits in the Art: From the Plains and Southwestern Indian Cultures (Kansas City: The Lowell Press, Inc., 1994), 106.

In A Persistent Vision: Art of the reservation Days, Richard Conn pictures two bear claw necklaces treated with red ochre, one owned by Fish Wolf Robe, a “traditional” Blackfeet man who died in the 1950s.[30]Denver: Denver Art Museum with the University of Washington Press, 1986. The second necklace, collected among the Crow and dated to the 1870s, is in fact made of horse hooves carved in the shape of bear claws, yet these are still covered by “layer upon layer” of red ochre—evidence, according to Conn, that the maker was responding to a spiritual vision. (There are several faux bear claw necklaces in the Peabody collections, and Feder and Chandler note that necklaces of this type are neither uncommon nor a recent phenomenon).

In summary, the formal properties of the Peabody’s grizzly claw collar support a relatively early date of construction compared to other museum examples, and it may well be the oldest surviving bear claw necklace in a public collection. In particular, the modification of the claws, their single drill holes made with a stone tool, the absence of trade materials, and the idiosyncratic nature of the design are features indicating that this necklace was made before the 1830s, when Euroamericans began to collect grizzly claw necklaces and to depict them in art. Because the necklace is so simple in form, essentially combining aspects of what Feder and Chandler called “Plains style” and “Style 3,” or Missouri River style bear claw necklaces, it is impossible to attribute the necklace to any particular historic tribal group on that basis. Nonetheless, it remains an important artifact of the expedition’s relationships with Native peoples.

Lewis and Clark Descriptions

Figure 10

Lakota warrior Rain in the Face exudes bear power

State Historical Society of North Dakota 1952-5136.

Glass-plate photograph, Frank B. Fiske (1890-1952). Fort Yates, North Dakota.

We know that the Corps of Discovery party first recorded seeing collars of grizzly claws while camping with a party of Yankton Dakota in what is now South Dakota on 30 August 1804 and 31 August 1804. As Paul Schullery notes in Lewis and Clark Among the Grizzlies, the appearance of the necklaces signaled to the explorers that they were now in grizzly country, although they had yet to encounter any of those formidable creatures.[31]Lewis and Clark Among the Grizzlies: Legend and Legacy in the American West (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2002). While counseling with the Yankton, including a chief named White Bear, John Ordway recorded that “their was Several of the Indians which had Strings of White Bears claws around their necks, which was 3 inches in length, & Strung as close as possable to each other.” If Ordway’s description is accurate, these Yankton men were wearing necklaces of the “Plains type”—that is, claws that were worn simply strung, without being attached to a fur or cloth foundation. Many Sioux people seem to have favored this basic “Plains” style, at the same time creating and wearing claw assemblages of various types and complexity (Figure 10).

Lewis and Clark continued to record seeing bear claw necklaces as their company moved across the Plains and into the Rocky Mountains. While their descriptions were often cursory, noting that men in various communities wore “claws of the bear” around their necks, their relatively long visits among the Shoshone and Nez Perce facilitated greater attention to detail. Lewis provided the most complete description of such a necklace while among the Shoshone:

The warriors or such as esteem themselves brave men wear collars made of the claws of the brown bear which are also esteemed of great value and are preserved with great care. These claws are ornamented with beads about the thick end near which they are pierced through their sides and strung on a throng or dressed leather and tyed about the neck commonly with the upper edge of the talon next to the breast or neck but sometimes reversed.[32]Moulton, Journals, 5:135.

From this description, the Shoshone necklace may have been a slightly more embellished version of the simple claw collar featured on the Nez Perce National Historical Park website (Figure 11). Feder and Chandler would classify both the Shoshone example described by Lewis and the later Nez Perce necklace as examples of the ubiquitous “Plains style.” It is entirely possible—especially given the value they placed on otter fur—that the Nez Perce and Shoshone also attached claws to otter-hide foundations. A potential Shoshone origin for the Lewis and Clark necklace cannot be entirely ruled out, given their relationship with the Corps and their relative poverty in trade goods. However, I have so far found no images of Shoshone or Nez Perce otter and grizzly claw collars in the literature for comparison.

A mutual interest in the ways of the grizzly provided common ground for conversation between Jefferson’s army officers and the warriors of the Plains and Plateau, many of whom displayed bear imagery on their garments and weapons. The American party killed dozens of grizzlies as they traveled, partly to obtain specimen skins, and they soon realized that bear claws and hides were a valuable addition to their dwindling supply of trade goods and gifts for Native leaders. So absorbed was Lewis by these formidable creatures—and probably so encumbered by their hides—that during an exchange of names, a Nez Perce chief pronounced him “Yo-me-kol-lick,” or “the white bearskin foalded.”[33]Ibid., 8: 79.

In turn, from the time that the American explorers first observed the formidable claw collars worn by Yankton men they encountered in August 1804, they expressed in their journals a growing respect for the skill and bravery implied by such displays. This was especially true among the gun-poor Shoshone, Clark commenting that “with the means they have of killing this animal it must really be a serious undertaking.”[34]Ibid., 5:135. It is clear that Indian men communicated to Lewis and Clark a strong connection between grizzly claw necklaces, leadership, and war. This network of associations may have worked in the explorers’ favor, since they arrived in Native communities packing grizzly skins and asking a host of related questions. Among the Nez Perce, Clark artlessly wrote: “This nation esteem the Killing of one of those tremendeous animals (the Bear) equally great with that of an enemy in the field of action—. we gave the Claws of those bear which Collins had killed to [chief] Hohastillpelp.”[35]Ibid., 7: 259. Hohots Ilppilp, whose name has been translated and interpreted as “a red, or bleeding, grizzly bear, his spiritual animal helper or guardian”[36]Ibid., 7:241n. must have instantly assumed that Lewis, Clark, and Collins were distinguished warriors.

Based especially on their interactions with Shoshone and Nez Perce men, Lewis and Clark understood that men wearing bear claw necklaces had personally killed the bears, and that those feats of bravery, determination and strength elevated their standing as warriors and leaders. This was almost certainly more true in 1800 than it was in 1850. Bears Arm, a Hidatsa, told anthropologist Alfred Bowers that “only very brave men ever owned [personal] Bear bundles before guns came, for the purchaser, having made his vow, was required to kill a grizzly bear unassisted,” adding that this was considered the most dangerous hunt to undertake.[37]Alfred W. Bowers, Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization (Moscow: University of Idaho, 1992), 357. Four Bears was a war leader, and was said to have earned his name because he fought “like four bears” against his enemies. According to the artist George Catlin, Four Bears wore his grizzly claw necklace “as a trophy—as an evidence unquestionable, that he had contended with and overcome that desperate enemy in open combat.”[38]George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, 2 vols. (1844; repr., New York: Dover, 1973), 1:146. Unfortunately, Catlin chose not to depict the necklace, which he described as having “fifty huge claws,” in his full-length portrait of Four Bears, for which the chief modeled in 1832. However, he reportedly purchased it from Four Bears, along with the rest of the ensemble in which he posed.[39]Ibid., 1:145.

Wearing a claw collar was the prerogative of a “made man” who had earned honors and distinction in war and by those who had accepted community ceremonial responsibilities. But as the abundance and quality of firearms increased and bear hunting became less dangerous, grizzly claws became more widely available through trade and purchase, and seem to have become less emblematic of personal kills. Maximilian observed Hidatsa warriors wearing “large and well-finished” necklaces of forty grizzly claws “for which they often give a high price,” and suggested that some of them had been obtained in trade from the Crow.[40]Thwaites, Travels, 24:368. But the association between claw necklaces, war honors, and leadership remained strong. A Mesquakie man cited by Feder and Chandler stated that men sometimes went to war against their Sioux enemies expressly to obtain a grizzly claw necklace, an accomplishment even greater than killing a bear. White Bull, a Lakota chief and nephew of Sitting Bull who was born in 1849, considered having killed eleven grizzlies from horseback with a rifle to be among his notable achievements, and he gave away twelve horses to commemorate that feat.[41]Joseph White Bull, Lakota Warrior, James H. Howard, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 30.

Conclusions

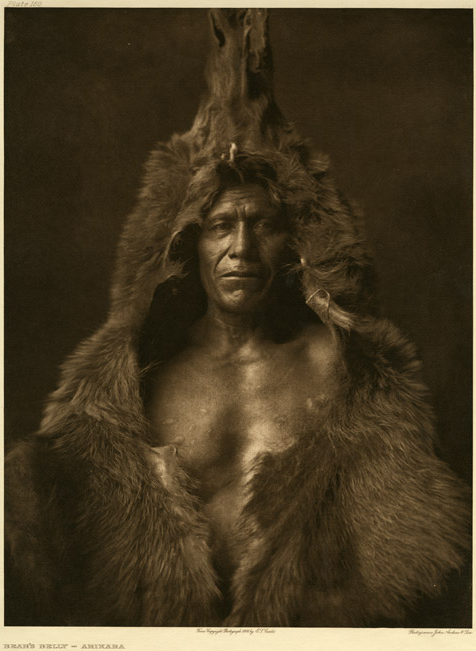

Bear’s Belly, a member of the medicine fraternity of

the Arikara, wrapped in his ceremonial bear skin.

Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

Archives & Special Collections, The University of Montana, Missoula Photogravure, ca. 1908, from The North American Indian

Communal, ritualized forms of bear hunting were probably most common before firearms and horses became readily available, partly because of the danger to the hunters. But also, social hunting was directly related to the descent groups, men’s societies, and community religious ceremonies responsible for the ritual management of bears. Lewis reported that before a hunt, Indians “paint themselves and perform all those supersticious rights commonly observed when they are about to make war upon a neighbouring nation”[42]Moulton, Journals, 4:31. Catlin saw and painted a bear dance staged prior to a grizzly hunt, in which Lakota men-some wearing the head and skin of bears-danced to communicate with the bear spirit “which they think holds somewhere an invisible existence, and must be consulted and conciliated before they can enter upon their excursion with any prospect of success.”[43]Catlin, Letters, 1:245. The Mandan and Hidatsa emphasized to both Lewis and Clark and to Maximilian that large parties of men were required to take a grizzly, and trader Edwin Denig observed the same of the Assiniboine nearly fifty years after the Lewis and Clark expedition. Denig, who was the American Fur Company trader at Fort Union (1837-1855) and was married to an Assiniboine woman, reported that men might fight a grizzly during an unexpected encounter, and that “The killing of a grizzly bear by a single man is no trifling matter and deservedly ranks next to killing an enemy. A coup is counted for that action in their ceremonies where they publicly recount their brave exploits.”[44]Denig, 105. But he judged such an event to be the exception, stating that it was more common for grizzlies to be hunted by groups of men, who smoked them out of their winter dens or surrounded them on horseback. Bears killed in this way were painted with vermilion, given prescribed gifts, offered a pipe to smoke, and were addressed with prayers. Across the plains, such ceremonial hunts were widely conducted prior to a war expedition.[45]Ewers, Bear Cult, 5.

Because of language barriers, their own biases, and the brevity of their journey, Lewis and Clark acquired a relatively superficial understanding of Indian life. While the captains understood those men who wore grizzly claw collars to be distinguished war leaders, they were unaware of the spiritual dimensions of warfare and of the singular importance that bears played in shamanism and in the religious life of warriors. Lewis studied grizzlies by killing them and measuring their bodies; Indians observed and learned from their behavior. Because grizzlies ate medicinal plants and were difficult to kill, they were seen as teachers of strength and healing. Short Feather, a nineteenth century Lakota, explained that bear spirits taught shamans their ceremonies, medicines, and songs: “When a man sees the Bear in a vision, that man must become a medicine man.”[46]James R. Walker, Lakota Belief and Ritual, ed. Raymond J De Mallie and Elaine A. Jahner (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1980), 116. James R. Murie, a Pawnee ethnographer who recorded the ceremonial life of his people in the early twentieth century, captured the integrated duality of meanings about bears when he stated that, “In olden times, every chief and member of the Bear Society [an organization of native doctors] owned a bear claw necklace” (Figure 12).[47]James R. Murie Ceremonies of the Pawnee, ed. Douglas R. Parks (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), 385.

At the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition, bear claw collars might have been worn by a variety of religious and war leaders whose relationship to bears was culturally shaped. Men’s societies of bear healers and bear dreamers were ubiquitous across the west.[48]Ewers, Bear Cult. Dreaming of bears, seeing them in a vision, or experiencing an unusual encounter indicated that the bears wanted to adopt or assist an individual, who would then be instructed how to establish and maintain a relationship. In some communities, the close association with bears that individual warriors and shamans sought was also cultivated and managed by social groups such as clans and associations. For example, among the Mandan descent groups orchestrated much of community ceremonial life, and before the smallpox epidemics of the 1830s, these included a grizzly bear clan.[49]Bowers, Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization, 176. Given that men might inherit responsibilities for bear ceremonies, or choose to purchase membership in a bear society, existing claws and necklaces were sometimes transferred from one person to another and renewed ritually. Murie describes the ceremonial renewal and transfer of an old bear claw necklace, during which the original claws were attached to a new otter hide.[50]Murie, 386.

It was considered honorable for chiefs and leaders to make gifts of their most valued objects, and Lewis and Clark probably received the grizzly claw necklace from a prominent man who was interested in cultivating a relationship with the Americans. Many of the other Native American objects they acquired, such as pipes and robes, were traditional “protocol” gifts customarily presented to important guests on behalf of the community, or were presents from individual chiefs with whom they exchanged symbols of rank, such as war and military shirts. In subsequent decades, grizzly claw necklaces were acquired by a number of important visitors to the Plains, including U.S. government officials; several styles are represented in the Smithsonian’s “War Department” collection of treaty and delegation gifts.[51]Candace S. Greene, Bonnoe Richard, and Kirsten Thompson, “Treaty Councils and Indian Deletations: The War Department Museum Collection,” American Indian Art, vol. 33, no. 1 (2007), 66-80. In 1832, the artist George Catlin witnessed Miniconjou Lakota chiefs disrobe and present their own head dresses, garments and bear claw necklaces to agents of the U.S. government and the American Fur company during a feast and council held near Fort Pierre.[52]Catlin, Letters, 1:228-29. As Lewis and Clark experienced, this form of “chiefly gifting” was by 1800 a well-established ritual of cross-cultural diplomacy that was almost certainly rooted in indigenous trading ceremonies. Lewis memorably exchanged garments with Cameawait, the Shoshone band leader, and during formal meetings with Native leaders, Lewis and Clark enacted the ritual of “dressing” chiefs by presenting them with military garments and accouterments.

On the other hand, bear claw necklaces were singular prestige items that could be given spontaneously as an act of honoring another. The Irish-Canadian artist Paul Kane described being given a bear claw necklace by a Blackfeet chief he painted during the 1840s, and his story makes clear that such collars were often cherished by their owners:

Mah-Min, “The Feather,” their head chief, permitted me to take his likeness, and after I had finished it, and it was shown to the others, who all recognized and admired it, he said to me, “You are a greater chief than I am, and I present you with this collar of grizzly bear’s claws, which I have worn for twenty-three summers, and which I hope you will wear as a token of my friendship.”[53]Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America (1859; repr., Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1996), 289.

While the grizzly claw collar brought back by Lewis and Clark cannot be traced to either a particular individual or even to a tribe of origin, it stands as a poignant reminder of the spirit in which it must have been given, and of a brief moment in which a relationship of “peace and friendship” between western tribes and the United States government still seemed possible. To a remarkable extent, it makes present that moment and the Indian people who encountered Lewis and Clark.

Notes

| ↑1 | Joseph Epes Brown, Animals of the Soul: Sacred Animals of the Oglala Sioux (Rockport, Massachusetts: Element Books, 1997), 84-85. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Lost Gift to Lewis and Clark Is Found,” The New York Times, 21 January 2004. Editorial, “An Unexpected Artifact” The New York Times, 22 January 2004. |

| ↑3 | Castle McLaughlin, Arts of Diplomacy: Lewis and Clark’s Indian Collection (Cambridge, Massachusetts and Seattle: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and Universityof Washington Press, 2003). |

| ↑4 | Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with related Documents, 1783-1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:476-79. |

| ↑5 | David R. Brigham, Public Culture in the Early Republic: Peale’s Museum and its Audience (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995), 108. |

| ↑6 | Charles Coleman Sellers, Mr. Peale’s Museum: Charles Willson Peale and the First Popular Museum of Natural Science and Art (New York: Norton, 1980), 312-16. |

| ↑7 | Charles C. Willoughby, “A Few Ethnological Specimens Collected by Lewis and Clark,” American Anthropologist, vol. 7, no. 4 (1905), 633-641. |

| ↑8 | Fergus Clunie, Yalo I Viti; Shades of Viti: A Fiji Museum Catalogue, (Suva, Fiji: Fiji Museum, 1986), 49; Fig. 3. |

| ↑9 | Norman Feder and Milford G. Chandler, “Grizzly Claw Necklaces,” American Indian Tradition, vol. 8, no. 1 (1961), 7-16. |

| ↑10 | (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2002), 53-54. |

| ↑11 | Irving A. Hollowell, “Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern Hemisphere,” American Anthropologist, 28 (1926), 1-175. |

| ↑12 | John Ewers, “The Bear Cult Among the Assiniboins and their Neighbors,” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, vol. 11, no. 1, 131-145. |

| ↑13 | Hallowell, 1-175; David Rockwell, Giving Voice to Bear: North American Indian Rituals, Myths, and Images of the Bear (Niwot, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart, 1991); Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders, The Sacred Paw: The Bear in Nature, Myth, and Literature (New York: Viking, 1985). |

| ↑14 | John Ewers, “The Awesome Bear in Plains Indian Art,” American Indian Art, vol. 7, no. 3 (1982), 36-45. |

| ↑15 | Norman Feder and Milford G. Chandler, “Grizzly Claw Necklaces,” American Indian Tradition, Vol. 8, no. 1 (1961), 11. |

| ↑16 | Maximilian, Prince of Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, Vol. 2, in Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Early Western Travels, 1748-1846 (Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark, 1906), 24:262. |

| ↑17 | Art of the Great Lakes Indians, Flint Institute of Arts, Flint Michigan, 1973; David W. Penney, Art of the American Indian Frontier: the Chandler-Pohrt Collection (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1992), Plate 46. |

| ↑18 | Moulton, Journals, 5:139. |

| ↑19 | Ibid., 7:224. |

| ↑20 | Davis Thomas and Karin Rohhefeldt, ed., People of the First Man; Life Among the Plains Indians in Their Final Days of Glory (New York: Promontory Press, 1982), 141. |

| ↑21 | “In the River of Time: Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara: Native Live Along the Upper Missouri River,” Exhibit catalog, Linden Museum, Stuttgart, 2000; Axel Schulze-Thulin, ed., Indianer der Prärien und Plains, (Stuttgart: Linden-Museum, 1987). |

| ↑22 | Thomas and Ronnefeldt, 237, 222. |

| ↑23 | The Linden necklace is an especially valuable example of Mandan style because according to Maximilian, he commissioned Mato Tope to create it. In his journal entry for 24 November 1833, Maximilian wrote: “I gave Mato-Topé a bear-claw necklace which he will complete for me. For this purpose I purchased an otter skin and blue glass beads at the Company store.” This fact would certainly account for the perhaps atypical patten of claws, while ensuring that the design composition was consistent with Mandan norms. Thomas and Ronnefeldt, 178. |

| ↑24 | Moulton, Journals, 8:318. |

| ↑25 | Edwin Thompson Denig, The Assiniboine (1930; repr. with a new introduction by David R. Miller, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 159. |

| ↑26 | John Ewers, Indian Life on the Upper Missouri (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968), Plate I. |

| ↑27 | Thomas and Ronnefeldt, 215. |

| ↑28 | Alfred W. Bowers, Hidatsa Social and Ceremonial Organization (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.) |

| ↑29 | James Hanson, Spirits in the Art: From the Plains and Southwestern Indian Cultures (Kansas City: The Lowell Press, Inc., 1994), 106. |

| ↑30 | Denver: Denver Art Museum with the University of Washington Press, 1986. |

| ↑31 | Lewis and Clark Among the Grizzlies: Legend and Legacy in the American West (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2002). |

| ↑32 | Moulton, Journals, 5:135. |

| ↑33 | Ibid., 8: 79. |

| ↑34 | Ibid., 5:135. |

| ↑35 | Ibid., 7: 259. |

| ↑36 | Ibid., 7:241n. |

| ↑37 | Alfred W. Bowers, Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization (Moscow: University of Idaho, 1992), 357. |

| ↑38 | George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, 2 vols. (1844; repr., New York: Dover, 1973), 1:146. |

| ↑39 | Ibid., 1:145. |

| ↑40 | Thwaites, Travels, 24:368. |

| ↑41 | Joseph White Bull, Lakota Warrior, James H. Howard, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 30. |

| ↑42 | Moulton, Journals, 4:31. |

| ↑43 | Catlin, Letters, 1:245. |

| ↑44 | Denig, 105. |

| ↑45 | Ewers, Bear Cult, 5. |

| ↑46 | James R. Walker, Lakota Belief and Ritual, ed. Raymond J De Mallie and Elaine A. Jahner (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1980), 116. |

| ↑47 | James R. Murie Ceremonies of the Pawnee, ed. Douglas R. Parks (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), 385. |

| ↑48 | Ewers, Bear Cult. |

| ↑49 | Bowers, Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization, 176. |

| ↑50 | Murie, 386. |

| ↑51 | Candace S. Greene, Bonnoe Richard, and Kirsten Thompson, “Treaty Councils and Indian Deletations: The War Department Museum Collection,” American Indian Art, vol. 33, no. 1 (2007), 66-80. |

| ↑52 | Catlin, Letters, 1:228-29. |

| ↑53 | Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America (1859; repr., Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1996), 289. |