“Ah-tón-we-tuck, Cock Turkey, Repeating His Prayer”

George Catlin (1796–1872)

Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. Permission via Creative Commons license.

About this portrait, Catlin wrote:

Ah-ton-we-tuck . . . is another Kickapoo of some distinction, and a disciple of the Prophet; in the attitude of prayer also, which he is reading off from characters cut upon a stick that he holds in his hands.

The above painting shows how diverse cultures and beliefs influenced the Kickapoo in the early 1800s. Painted either in the Fort Leavenworth area in 1830 or Illinois in 1831, Cock Turkey’s ritual was likely influenced from the teachings of a Methodist minister. The Prophet, Tenskwatawa, was a Shawnee leader and the younger brother of Tecumseh.[1]George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, reprint (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1926) 2:112–13.

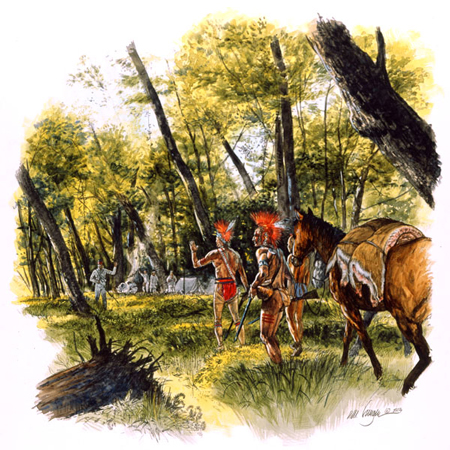

Perhaps more than any North American people, the Kickapoo exemplify the transitory nature of the native nations encountered during the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Kickapoo movements were so frequent and diverse that the tribe cannot be associated with any single geographic area. They moved in various directions from Detroit on the Great Lakes to Wisconsin, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and even Mexico. By 1803, many had migrated farther west to avoid European settlement, and there was at least one village near Ste. Genevieve on the Mississippi River.[2]Louis Houck, A History of Missouri from the Earliest Explorations and Settlements Until the Admission of the State into the Union (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, 1908), 362.

Algonquian-speaking, the Kickapoo are linguistically and culturally similar to the Sauk and Fox; and the Mascouten whom they eventually absorbed. As they migrated, the people shifted loyalties with relevant, but competing, colonial powers: the French, the English, and the Spanish. Such positive relations with the United States were never established.[3]Charles Callender, Richard K. Pope, and Susan M. Pope, Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast Vol. 15, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 656, 663.

As a deterrent to Osage raids on its citizens, the Spanish had encouraged Shawnees, Lenape Delawares, and Kickapoos to settle in their Missouri and Kansas territories. Spelled Kickpo, Kickapoo, and Kick, the expedition journalist make it clear that the Osage People were enemies of the Kickapoo. In March 1804, Lewis, Clark, one of the Chouteaus, and Charles Gratiot went up the Missouri to stop a Kickapoo war party headed toward the Osage. The Chouteaus had for years developed trade with the Osage and by 1800, the Osage trade accounted for half of the St. Louis trade.[4]“Chouteau Family,” Oklahoma Historical Society, accessed 21 December 2020, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CH056.. The ability to protect your partners from harm was a promise given to induce trade agreements.

In 1819, migration to reservations west of the Missouri began taxing the land’s resources and prompted hostilities between the Osage and an alliance of Kickapoo, Delaware, and Shawnee.[5]Houck, 196–97; Callender, Pope and Pope, 662. As a result, in 1832, the Kickapoo were assigned to a new tract west of the Missouri. Many instead migrated to Arkansas, Texas, and Mexico. Eventually most were forced to move to Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma.[6]Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1912), 1:684–85.

Today, there are three federally recognized Kickapoo tribes in the United States: the Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas, the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, and the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas. The Tribu Kikapú still resides in Mexico.[7]“Kickapoo People,” Wikipedia, accessed 20 December 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kickapoo_people.

Selected Encounters

May 17, 1804

St. Charles court martial

Privates Hugh Hall and John Collins misbehaved in St. Charles the previous night and today face a court martial. Some visiting Kickapoos tell Clark that the Sauk and Osage are at war—a thing the captains have been trying to prevent.

January 1, 1804

New Year's shooting contest

Winter Camp at Wood River, IL Clark stages a shooting contest with the locals and notes that two men (perhaps Reed and Windsor) were drunk. He meets with a new washer woman, and a visitor tells him about the Mandan Indians and their country. The captains begin their weather diaries.

September 21, 1806

St. Charles hospitality

St. Charles, MO The boatmen paddle or row the forty-eight miles from La Charrette to St. Charles. They are greeted by the latter’s citizens with great cheer and hospitality. Lewis starts a letter to Thomas Jefferson.

May 22, 1804

Trading with Kickapoo hunters

After a very rainy night, the expedition sets out at 6 am, travels 18 miles, and camps near the mouth of the Femme Osage River in present-day Missouri. They trade with some Kickapoos for four deer.

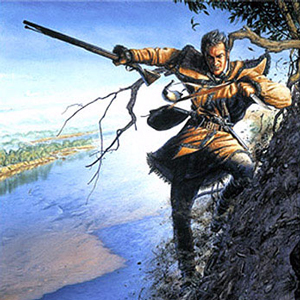

May 23, 1804

Lewis escapes death

Lewis climbs the pinnacles of Tavern Rock, slips, and manages to escape with the help of his knife. In Tavern Cave, Clark adds his name among the graffiti left by earlier travelers.

March 19, 1804

Intercepting a war party

Wood River Camp, IL According to the Weather Diary, Clark and Lewis are on a trip to St. Charles in an attempt to prevent a large war party of Kickapoos from attacking the Osages.

March 20, 1804

A chorus of frogs

Wood River Camp, IL Clark and Lewis travel by boat from St. Charles where they had intercepted a Kickapoo war party. Clark reports hearing frogs for the first time this season.

March 21, 1804

Return to Camp Dubois

Winter Camp at Wood River, IL Lewis, Clark, Auguste or Pierre Chouteau, and Charles Gratiot return to winter camp having been to St. Charles where they stopped a Kickapoo war party. After a long gap, Clark’s field notes resume.

March 23, 1804

Kickapoo update

At winter camp across the Mississippi above St. Louis, the man sent up the river to check the status of a Kickapoo war party returns with a letter from François Saucier, the commander of Portage des Sioux.

May 25, 1804

Last 'White' village

The expedition reaches La Charrette—the last settlement of “white people on this River . . . .” Here the captains meet trader Régis Loisel who shares valuable information about where they are going.

May 5, 1804

Sauk and Kickapoo visitors

In St. Louis, Lewis prepares for departure up the Missouri River. Across the Mississippi at Camp River Dubois, Clark receives Sauk and Kickapoo visitors.

Notes

| ↑1 | George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, reprint (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1926) 2:112–13. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Louis Houck, A History of Missouri from the Earliest Explorations and Settlements Until the Admission of the State into the Union (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, 1908), 362. |

| ↑3 | Charles Callender, Richard K. Pope, and Susan M. Pope, Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast Vol. 15, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 656, 663. |

| ↑4 | “Chouteau Family,” Oklahoma Historical Society, accessed 21 December 2020, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CH056. |

| ↑5 | Houck, 196–97; Callender, Pope and Pope, 662. |

| ↑6 | Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1912), 1:684–85. |

| ↑7 | “Kickapoo People,” Wikipedia, accessed 20 December 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kickapoo_people. |