The journalists mention only one direct encounter with Potawatomi people. Clark and the boat crews had just arrived at the mouth of the Wood River to establish camp for the winter. To his astonishment two canoes of drunken paddlers perilously navigated wind-blown waves on the Mississippi River and set up camp on the other side of the river—likely the Wood, not the Mississippi.

These horticulture-based people traditionally spoke Potawatomi, a distinct Algonquian language. By 1800, they had established successful trade with the French to the north and the Spanish in St. Louis. They resided in a large region surrounding the southern half of Lake Michigan between the Mississippi River and Lake Erie and extending south to the mouth of the Illinois River.

In 1803 the Potawatomi had already participated in two treaties, most notably the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. By 1867, they would be involved in 52 more treaties and forced to move onto small reservation allotments.[1]James A. Clifton, Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast Vol. 15, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 725–26, 728, 736.

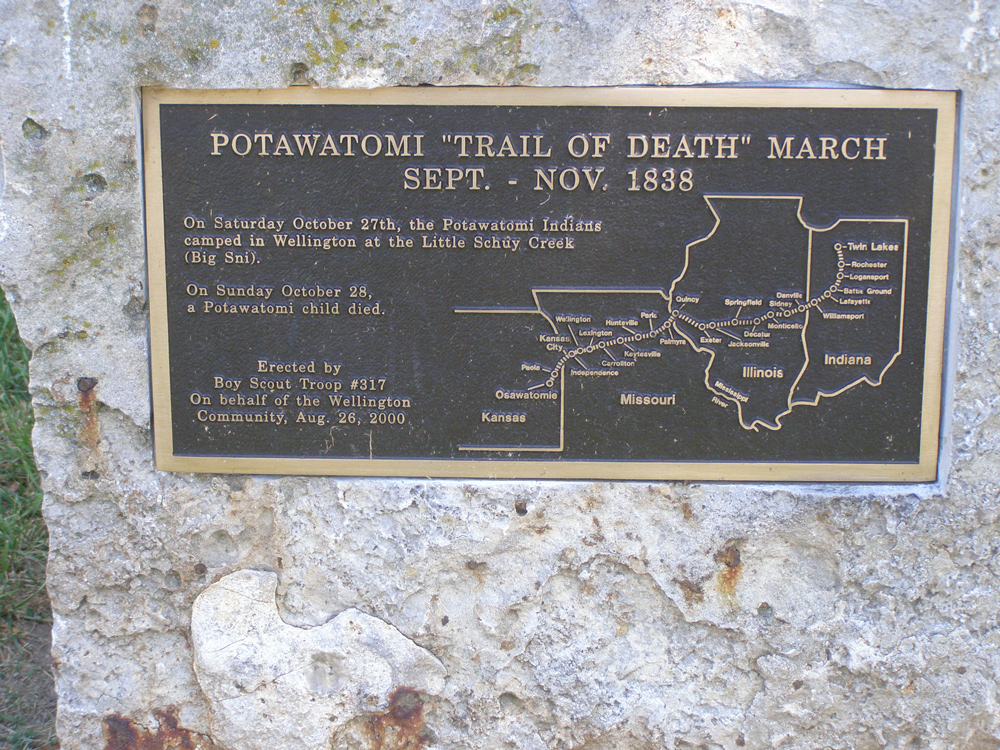

Trail of Death

Trail of Death Marker, Wellington, Missouri

By Chris Light. Permission via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The text of the marker is:

Potawatomi “Trail of Death”

Sept. – Nov. 1838

On Saturday October 27th, the Potawatomi Indians camped in Wellington at the Little Schuy Creek (Big Sni). On Sunday October 28, and Potawatomi child died.

Erected by Boy Scout Troop #317 On behalf of the Wellington Community, Aug. 26, 2000

The Potowatomi’s most famous migration is known as the Trail of Death. The march is well-document in first-hand letters from Father Benjamin Marie Petit to his Bishop in Vincennes. Sketches were made by artist George Winter who some call the George Catlin of Indiana.[2]David Lottes, Ouabache in Jessica Diemer-Eaton, The First Peoples of Ohio & Indiana: Native American History Resource Book (Woodland Indian Educational Programs, 2014), 198. One of the Father’s letters during the march describes this scene at the confluence of the Wabash and Eel rivers in Indiana:

[16 September 1838] I found the camp just as you saw it, Monseigneur, at Logansport—a scene of desolation, with sick and dying people on all sides. Nearly all the children, weakened by the heat, had fallen into a state of complete languor and depression.[3]Irving McKee, “The Trail of Death: Letters of Benjamin Marie Petit,” Indiana Historical Society (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1944), 98–99, available at … Continue reading

The Potawatomis’ Trail of Death was just one of several Indian Removals that worried Clark. As Superintendent of Indian Affairs between 1822 and his death in 1838, he oversaw the arrival of all Indians removed from the Great Lakes and Ohio River regions and facilitated their movement to their allotted lands west of the Mississippi.[4]for more on this period, see “Indian Removal: Indian Removal Act,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_removal#Indian_Removal_Act.

Today, one can find many sources of information about the Potawatomi people. The Trail of Death is a regional historic trail with historical markers at each campsite. The people now constitute seven federally recognized tribes in the United States, and seven First Nations in Canada.[5]“Potawatomi,” Wikipedia accessed 5 December 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potawatomi.

Synonymy

They call themselves potewatmi. The name has no literal translation, but folk etymology adopted the meaning ‘people of the place of fire’ which likely evolved from the early Jesuit priests calling them “Nation of Fire.” (Hodge 2:289). They sometimes called themselves neshnabé meaning ‘person’ or perhaps ‘Indian, not European American’. Clark spelled their name as Potowautomi. Other spellings in the literature include Pottawatomi, Pottawatomie, Pedadumies, Oupouteouatamik, Pouës, Poux and the like.[6]Clifton, 741.

For Further Reading

William Clark Indian Diplomat by Jay H. Buckley, University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

Selected Encounters

July 20, 1804

Drouillard is sick

The expedition passes Water-which-Cries and Waubonsie creeks along the present Nebraska and Iowa border. Lead hunter George Drouillard is sick, and Lewis collects two specimens of clover.

July 16, 1804

Stuck on a sawyer

The expedition sails twenty miles up the Missouri River and camps near a ‘Bald Pated’ prairie at the Nishnabotna River. In Washington City, President Jefferson addresses a visiting Osage delegation.

December 12, 1803

Rivière à Dubois arrival

Winter Camp at Wood River, IL Clark takes the boats past Florissant village, now a suburb of St. Louis, and then arrives at the Riviére á Dubois just below the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. Lewis is in St. Louis collecting data.

Notes

| ↑1 | James A. Clifton, Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast Vol. 15, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 725–26, 728, 736. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | David Lottes, Ouabache in Jessica Diemer-Eaton, The First Peoples of Ohio & Indiana: Native American History Resource Book (Woodland Indian Educational Programs, 2014), 198. |

| ↑3 | Irving McKee, “The Trail of Death: Letters of Benjamin Marie Petit,” Indiana Historical Society (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1944), 98–99, available at https://archive.org/details/trailofdeathlett141peti. |

| ↑4 | for more on this period, see “Indian Removal: Indian Removal Act,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_removal#Indian_Removal_Act. |

| ↑5 | “Potawatomi,” Wikipedia accessed 5 December 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potawatomi. |

| ↑6 | Clifton, 741. |