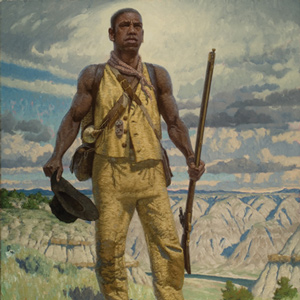

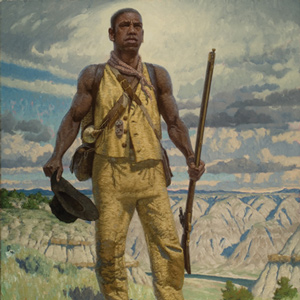

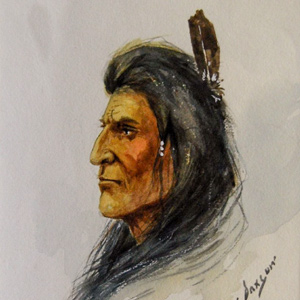

Pachtüwa-Chtä. An Arrikkara Warrior

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.[1]“Pachtüwa-Chtä, Arrikkara Krieger. Pachtüwa-Chtä, Geurrier Arrikkara. Pachtüwa-Chtä, Arrikkara Warrior.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 9, 2019. … Continue reading

Spelled variously in the expedition journals—Rickerie, Recreries, Richarees, Ree, Ricare, Arickaree, Rick, Rics, and Star rah he—Clark sometimes called the Arikara people Pawnee due to their similar linguistic origins—both were Caddoan-speaking people. They are also known as Sahnish and Hundi.

When they met the Lewis and Clark Expedition in early October 1804 at the village of Sawa-haini above present-day Mobridge, South Dakota, the Arikara were reduced to three villages. There, the captains met traders, Joseph Garreau, Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, and Joseph Gravelines. The latter would serve as interpreter and pilot the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) on its return to St. Louis in spring 1805. Arikara Chief Too Né, also known as Piahito or Eagle Feather, came on board as a diplomat in the captains’ efforts to bring peace between the Arikaras, Mandans, and Hidatsas. The chief agreed to travel to Washington City as an Arikara delegate, and his unfortunate death during that trip had a significant impact on American fur trade interests on the Missouri River and affect the lives of several expedition members.

Having lived a year with the Arikara, St. Louis-based trader Tabeau informed the captains about the people and later wrote a formal report not published for over a century. In it, he describes the people’s current decline:

Of the eighteen fairly large villages, situated upon the Missouri at some distance from each other, the Ricaras are reduced to three mediocre ones, the smallest of which is a league from the other two. They comprise in all about five hundred men bearing arms. Some hostile inroads but, in particular, the smallpox unexpectedly made this terrible ravage among them. These three villages are today composed of ten different tribes and of as many chiefs without counting an infinity of others who have remained, after the disaster, captains without companies.[2]Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, Tabeau’s Narrative of Loisel’s Expedition to the Upper Missouri River, Annie Heloise Abel, Ed., translated from French by Rose Abel Wright, (Norman: University of … Continue reading

Prior to the smallpox epidemics of the late 18th-century, Arikara and Pawnee bands lived in present-day Nebraska and Kansas practicing the Central Plains Village tradition. Warfare and disease prompted bands of Arikara to move north and form larger villages. In addition to hunting, they grew corn, squash, beans, watermelon, sunflowers and native tobacco (Nicotiana quadrivalvis).[3]Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast Vol. 13, Plains, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 368.

Tabeau’s narrative elaborated on frequent and violent infighting among the Arikara survivors. He also stated rather bluntly, “[T]he Ricaras are the most simple and the most stupid of all the Savages of the Upper Missouri.”[4]Tabeau, 131–32. The captains’ “Estimate of the Eastern Indians” was more generous of the people and emphasized their role as victims at the hands of the Sioux:

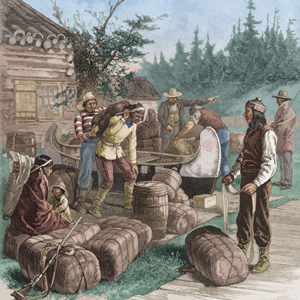

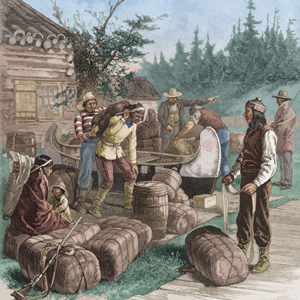

The Tetons [Lakota Sioux] claim the country around them. Though they are the oldest inhabitants, they may properly be considered the farmers or tenants at will of that lawless, savage and rapacious race the Sioux Teton, who rob them of their horses, plunder their gardens and fields, and sometimes murder them, without opposition. If these people were freed from the oppression of the Tetons, their trade would increase rapidly, and might be extended to a considerable amount. They maintain a partial trade with their oppressors the Tetons, to whom they barter horses, mules, corn, beans, and a species of tobacco which they cultivate; and receive in return guns, ammunition, kettles, axes, and other articles which the Tetons obtain from the Yanktons of the N. and Sissatones, who trade with Mr. Cammeron, on the river St. Peters [Des Moines].[5]Moulton, Journals, 3:400–01.

Both Tabeau and the captains were of the mind that the Arikara were ready to ally with the Mandan, a move that favored American trade interests in the region. Too Né, chief of the Waho-erha band traveled with the expedition to the Knife River Villages where they smoked the pipe of peace with the Hidatsas and Mandans. In April 1805, the expedition left the Knife River with news of an Arikara band wanting the move there, and Too Né traveled in the barge to St. Louis. His delegation would continue to Washington City where he met Thomas Jefferson, Senator Samuel Latham Mitchill, and made a map of his Arikara world.[6]Too Né’s map is featured in We Proceeded On, May 2018, available at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol44no2.pdf.

Too Né would die during the trip, and Tabeau’s and the Captains’ expectations would not be met for several decades. In fact, in the two decades after the expedition, the Arikara were a fierce obstacle to American expansion in the upper Missouri River. In 1807, the Arikara successfully prevented the return of Mandan Chief Sheheke from his Washington City journey. Nathaniel Pryor, a sergeant in the Lewis and Clark Expedition, would lead an armed force to get the Sheheke and his retinue past the Arikara. That attempt failed, and expedition alumni George Shannon and George Gibson would both be wounded. Some suggest the failed attempts to return Sheheke to his home was a contributing factor in the suicide of Meriwether Lewis.[7]See “Lewis’s Ultimate Failure” in Sheheke’s Delegation. See also The Last Journey of Meriwether Lewis by Clay S. Jenkinson.

Sheheke was eventually returned, only to be killed later by some Arikara, and the people continued to hamper American traders trying to get past their villages on the Missouri River. In 1823, former member John Collins was one of several men killed by the Arikara during a battle with William Henry Ashley’s fur trade party.[8]See also “Ashley and Henry” in Post-expedition Fur Trade by W. Raymond Wood. That skirmish resulted in a punitive campaign of 250 U.S. Army and 750 Sioux soldiers led by Colonel Henry Leavenworth. After several days of shelling, the Arikara escaped by night seeking sanctuary in Mandan and Hidatsa villages.[9]Parks, 367.

In 1862, decimated by disease, wars, and treaties, the Arikara fully allied with the Mandans and Hidatsas moving to the Fort Berthold Reservation, a remnant of the traditional Hidatsa territory at the time of the expedition. The alliance is known today as The Three Affiliated Tribes or the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.

Selected Pages and Encounters

Assessing the Legacy of Lewis and Clark

by Clay S. Jenkinson

The author proposes a few metaphors for the Lewis and Clark story, not in any definitive way, but merely to help us all think about the legacy of the expedition.

Too Né’s Delegation

by Joseph A. Mussulman

A delegation of chiefs from the Arikara, Ponca, Omaha, Otoe, Iowa, and Missouria nations sailed down the Missouri with Corporal Warfington on the expedition’s keelboat in the spring of 1805. Early in January, 1806, President Jefferson greeted them in Washington City with a formal speech.

Joseph Gravelines

by Clay S. Jenkinson

The Arikara-resident trader and interpreter Gravelines proved to be so reliable and so good at the immediate tasks put to him that long after the Lewis and Clark Expedition he was employed by the United States government to represent its interests among the Arikara.

This Arikara leader rode upriver with the expedition in the weeks that followed to negotiate a peace settlement with the Mandan. In the spring of 1805 he went down river with the barge to St. Louis. After a series of delays, he went to Washington, DC, to meet with President Jefferson.

Meet the Three Affiliated Tribes

Interviews with tribal members

My name is Tex Hall. I’m the tribal chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes . . . the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation . . . here at Fort Berthold at present day New Town, North Dakota. I would like to speak a little Hidatsa because I am Mandan and Hidatsa.

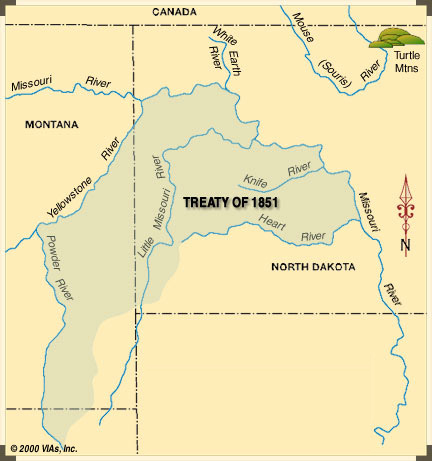

Hidatsa Territory

Becoming the Fort Berthold Reservation

After leaving Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805, the expedition traveled for several days through Hidatsa territory. Much of that area would become the Fort Berthold Reservation of the Three Affiliated Tribes, a coalition of Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara.

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

October 1, 1804

The Cheyenne River

Little Bend Rec. Area, SD Upon reaching the Cheyenne River, Lewis and Clark meet fur trader Jean Vallé who tells them about that river. They notice the ash tree leaves are turning color, and Lewis adds three plant specimens to the collection.

October 4, 1804

Turning around

Forest City, SD The day begins by dropping back three miles to the start of a better river channel. Various Indians on the shores are avoided, and camp is across from an abandoned Arikara village.

October 6, 1804

Empty Arikara village

Swan Creek, SD The expedition comes to a recently inhabited Arikara village. They find bull boats, baskets, and a garden. On the river, the numerous channels make navigation difficult.

October 7, 1804

Grizzly bear tracks

Below Mobridge, SD At the mouth of the Moreau Rive, the travelers their first grizzly bear tracks. They come across another empty Arikara village and camp above an island with many grouse.

October 8, 1804

Arikara village Sawa-haini

Arikara Village Sawa-haini, SD The expedition boats head up the shallow Missouri River bear present Mobridge. Camp is near an active Arikara village where the interpreter Joseph Gravelines is found. They also find abundant buffaloberries near the creeks.

October 9, 1804

Tabeau and Too Né

Arikara village Sawa-haini, SD The Arikara council is delayed by weather. The captains meet several key people including Pierre-Antoine Tabeau and Chief Too Né. York fascinates the Arikara who apparently have never seen a black man before.

October 10, 1804

An Arikara council

Arikara village Sawa-haini, SD Above present-day Mobridge, a council with the Arikaras is held, and the standard speeches and gifts are given. Clark appears a bit upset when York hams it up for the Indians.

October 11, 1804

Gifts and promises for the Arikara

Rogo Bay Rec. Area, SD In a council, Arikara chiefs promise to keep the river open to trade with the United States. The boats then move to another village up the river. Despite their poverty, the Indians give the expedition food.

October 12, 1804

More Arikara diplomacy

Shaw Creek Rec. Area, SD The morning is spent parleying and trading with the Arikaras. At 1 pm, with the sounding horn and fiddle playing, the expedition heads up the Missouri River.

October 13, 1804

Newman's court-martial

Vanervorsite Bay Rec. Area, SD John Newman is tried for making mutinous remarks, and he is removed from the permanent party engaged in “North Western discovery.” Some Arikaras tell a legend about some unusual rocks.

October 14, 1804

Newman's punishment

Below Fort Yates, ND The day is rainy and most of the leaves have fallen as the expedition enters present-day North Dakota. The execution of Newman’s sentence startles Arikara Chief Too Né.

October 15, 1804

Arikara exchanges

Fort Yates, ND As they travel past various hunting camps, the men trade with the Arikaras. A young Indian girl traveling with the boats is summoned to shore.

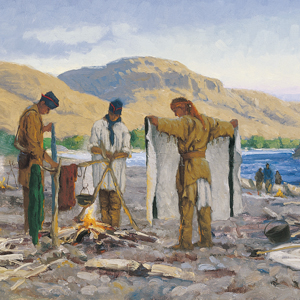

The Corps observed an Indian strategy for hunting game. As men on horseback herded pronghorns—”goats or Antelope,” Clark called them—into the river, boys swam among them and killed some with sticks, while others on shore shot them with bows and arrows.

October 16, 1804

"Goat" hunting

Above Beaver Creek, ND The expedition struggles fourteen river miles passing countless sandbars. They see the Indians killing pronghorns, and the Indians make merry the greater part of the night. Elsewhere, the Hunter and Dunbar Expedition sets out.

October 17, 1804

Too Né tells stories

Cannon Ball, ND The men tow the boat six miles against a headwind and camp below the Cannonball River. Clark walks the shore with Chief Too Né who shares Arikara stories. Clark learns that pronghorns swim the river in a twice-yearly migration.

October 24, 1804

Mandan-Arikara council

Washburn, ND The morning brings snow and rain as the boats make seven more miles up the Missouri reaching a Mandan camp. The captains, Too Né, and a Mandan chief meet with ceremony and smoking.

October 29, 1804

Mandan-Hidatsa-Arikara peace

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND The standard diplomatic speech is given at a council with the Mandans and Hidatsas. The captains ask them to also smoke the pipe of peace with Arikara Chief Too Né. Medals, flags, and clothing are given as gifts.

November 10, 1804

Hewing and guttering

Fort Mandan, ND Cottonwood logs are shaped with axes and adzes so that they can be used to cover cabin roofs. An Indian—likely The Coal of Mitutanka—and his wife visit.

November 20, 1804

Diplomatic complications

Fort Mandan, ND Three chiefs from the Ruptáre village say that the Sioux will punish the Arikaras if they follow the captain’s peace initiatives. Charbonneau brings a large load of meat and furs, and the captains move into their room.

December 1, 1804

Hudson's Bay Company visitor

Fort Mandan, ND George Henderson of the Hudson’s Bay Company visits, and Sgt. Ordway describes their business at the Knife River Indian villages. A delegation of Cheyennes and Arikaras arouse Mandan suspicions.

December 2, 1804

Cheyenne delegations

Fort Mandan, ND When four Cheyennes arrive, the captains give the standard diplomatic speech, gifts of tobacco, a flag, and demonstrations of many ‘curiosities.’ A letter of warning to the Sioux and Arikaras is also handed to the visitors.

February 22, 1805

Fort Mandan rain

Fort Mandan, ND Fort Mandan receives its first rain since last November. Lewis’s hunting group rests while the others work to free the boats from the river’s snow and ice.

February 28, 1805

Arikara and Sioux news

Fort Mandan, ND Traders arrive with news of the Arikaras and Sioux and two plant specimens. About six miles from the fort, several men cut down cottonwood trees to make dugout canoes.

March 16, 1805

Native bead-making

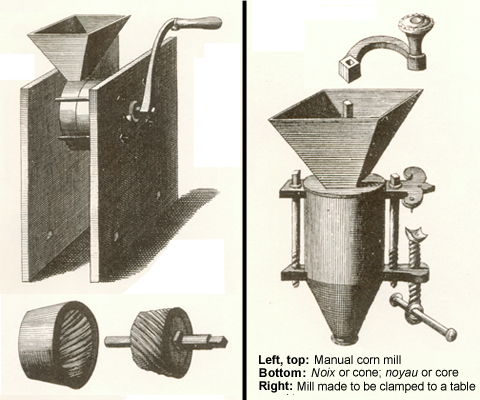

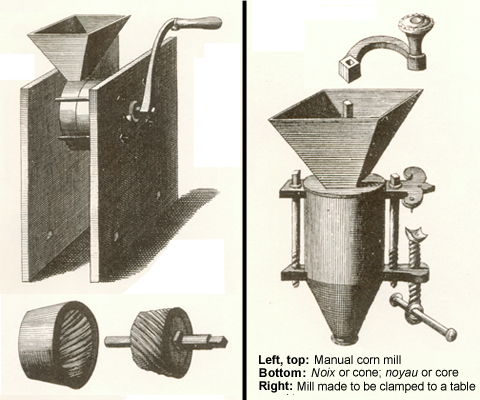

Fort Mandan, ND Long-time Upper Missouri Villages trader Joseph Garreau shows the captains how the Arikara melt glass trade beads and re-make them more to their liking.

April 6, 1805

A diplomatic delay

Some visiting Mandans tell the captains that the entire Arikara nation has moved to one of their old villages nearby. The captains postpone leaving Fort Mandan to learn more.

April 7, 1805

Leaving Fort Mandan

The permanent party leaves Fort Mandan bound for the Pacific Ocean. They make it only as far as Mitutanka, one of the Knife River Villages. In the barge, the return party heads towards St. Louis.

October 8, 1805

A canoe accident

Potlatch River, ID (Colters Creek) The Clearwater River has many rapids, stretches of calm, and islands inhabited by Nez Perce fishers. Travel stops after a canoe accident. In St. Louis, General Wilkinson tells of sick Indian delegates and the value of interpreter Pierre Dorion.

August 11, 1806

Cruzatte shoots Lewis

White Earth River and Four Bears Village, ND While hunting elk, Pierre Cruzatte accidentally shoots Lewis through the buttock. Clark meets fur traders who share news of the barge, Indian wars, and shifting trade alliances.

August 21, 1806

Arikara Villages

Above Mobridge, SD At the upper and lower Arikara villages, several councils are conducted between the Mandans, various Arikara chiefs, and visiting Cheyennes. The captains see Rivet, one of their 1804 engagés, who says a chief from an earlier Washington City delegation has died.

August 25, 1806

Empty Lakota encampment

Above Pierre, SD The boats stop at the Cheyenne River so that the captains can take celestial observations, and the men can hunt. Passing an empty Lakota encampment, they recall the “Troubleson Tetons” on their way up the river in 1804.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Pachtüwa-Chtä, Arrikkara Krieger. Pachtüwa-Chtä, Geurrier Arrikkara. Pachtüwa-Chtä, Arrikkara Warrior.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 9, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c40f-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, Tabeau’s Narrative of Loisel’s Expedition to the Upper Missouri River, Annie Heloise Abel, Ed., translated from French by Rose Abel Wright, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1939), 123-125. |

| ↑3 | Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast Vol. 13, Plains, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 368. |

| ↑4 | Tabeau, 131–32. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, Journals, 3:400–01. |

| ↑6 | Too Né’s map is featured in We Proceeded On, May 2018, available at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol44no2.pdf. |

| ↑7 | See “Lewis’s Ultimate Failure” in Sheheke’s Delegation. See also The Last Journey of Meriwether Lewis by Clay S. Jenkinson. |

| ↑8 | See also “Ashley and Henry” in Post-expedition Fur Trade by W. Raymond Wood. |

| ↑9 | Parks, 367. |