President Thomas Jefferson instructed Lewis to “make yourself acquainted . . . with the names of the nations & their numbers.” When Captains Lewis and Clark stepped of the boat, they did even more. They also recorded their impressions of the strange societies and exotic cultures they encountered. In this article from We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, historian James P. Ronda examines the captains’ role as ethnographers.—Ed.[1]For the original article, see on our sister site James P. Ronda, “”The Names of the Nations”: Lewis and Clark as Ethnographers,” We Proceeded On, November 1981, vol. 7 no. 4 … Continue reading

The [Chippeway] Snow-shoe Dance

by George Catlin (1796-1872)

From Wiki Commons, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ojibwa_dance.jpg accessed 12 December 2022.

Of the above scene, George Catlin wrote the following:

Many were the dances given to me on different places. of which I may make further use and further mention on future occasions: but of which I shall name but one at present, the snow-shoe dance (Plate 243), which is exceedingly picturesque, being danced with the snow shoes under the feet, at the falling of the first snow in the beginning of winter; when they sing a song of thanksgiving to the Great Spirit for sending them a return of snow, when they can run on their snow shoes in their valued hunts, and easily take the game for their food.[2]George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, 4th Ed. (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1842), 2:139.

At a recent conference in Canada I presented a paper on the Lewis and Clark confrontation with the Brule Teton Sioux at the mouth of the Bad River. At the end of the session one of my Canadian friends said politely but a bit sarcastically, “what’s all the fuss about Lewis and Clark? After all, Alexander Mackenzie did it first in 1793!” Of course my friend up North was right. Mackenzie was the first European to make a land passage of the northern part of the continent and publication of his book prodded President Thomas Jefferson into organizing an American expedition to the Pacific. But beyond that narrow point, my Canadian colleague was quite mistaken. When the great Mackenzie ventured from Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca down the Peace River to the Parsnip and on to the Bella Coola and salt water, he was simply a North West Company agent looking for new business opportunities. He wore but one hat. When the captains struggled up the Missouri and across those tremendous mountains to the sea, they wore many hats. They were explorers, soldiers, diplomats, cartographers, naturalists, and advance agents of American enterprise. They were something else as well, something many histories fail to mention. Lewis and Clark were capable ethnographers endeavoring to gather and record information about the Native American peoples of the West and Pacific Northwest.[3]Verne F. Ray and Nancy O. Lurie, “The Contributions of Lewis and Clark to Ethnography,” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 44 (1954), 358–370. Lewis and Clark knew what we so often forget—that western America was no empty continent but a crowded wilderness. Thomas Jefferson’s passion to explore the West included a powerful desire to know the native peoples and cultures of the region. If the captains were called upon to find the Passage to India, they were equally commanded to record “the names of the nations” along the way.[4]Thomas Jefferson, “Instructions to Lewis, 20 June 1803,” in Donald D. Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 1783–1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana, 1978), … Continue reading

An Intricate Puzzle

To appreciate the expedition’s ethnographic contributions we must understand the difference between ethnographers and ethnologists. Disguised as travellers, traders, missionaries, and explorers, ethnographers have been around a long time. These people often did their work without realizing they were engaged in ethnoghraphic study. They simply recorded their impressions of the strange societies and exotic cultures they encountered. They described Indian life on a part-time basis, considering such activity incidental to their primary tasks. Jesuit missionaries in Canada studied Indian ways in order to save lost souls; David Thompson noted native exchange systems to facilitate future trade operations. Lewis and Clark were also part-time participant observers of Native American life. As such they belonged to a long and honorable tradition in North America that includes Father Paul Le Jeune, James Adair, Nicolas Perrot, and the captains’ contemporaries Alexander Henry the Younger and Zebulon Pike. Everything these men noted about Indians—clothing, houses, village locations, languages, customs, and economy—they recorded in the service of business enterprise, government policy, or religious zeal. They made no pretense at being scientific observers. This does not diminish the accomplishments of the early ethnographers or lessen the value of their work, but it does remind us of the limitations of their accounts. As arresting as they are, they are imperfect, incomplete pieces of historical evidence. What Lewis and Clark did not do—and we ought not expect them to have done—was to paint a unified, coherent portrait of any Indian culture. They simply did not think in those terms. What they did do was to leave us priceless maps and journals that comprise the pieces of an intricate puzzle. Here is a bit of the puzzle informing us when to harvest and how to cook Upper Missouri corn; here is a piece of a Mandan creation story recorded in 1804 and still told as late as 1929; and here is yet another puzzle part, this one revealing Indian behavior at funerals. And the list of bits and pieces could go on and on—what Indians did with their horses at night, how adoption made it possible for enemies to trade in peace, and when to consult the sacred medicine stone. There is even a detailed description of the complex Arikara bead making process.[5]Martha W. Beckwith, Mandan-Kidatsa Myths and Ceremonies (New York, 1937), 18; Patrick Gass, A Journal of the voyages of a Corps of Discovery (Pittsburgh, 1807; reprinted, Minneapolis, 1958), 79–80; … Continue reading But in all of this we must locate, identify, sort, and arrange those pieces ourselves, full well knowing that some important ones may turn up missing. As we analyze the information Lewis and Clark collected, we assemble most challenging puzzle.

Lewis, Clark, Ordway, and the other expedition journalists were ethnographers. Modern-day ethnologists are a very different breed of cat. Ethnologists are scientists who study many cultures with an eye towards developing concepts of human social development and behavior applicable to many diverse peoples. Ethnologists are full-time specialists committed to accurate, impartial observation.[6]Wendell H. Oswalt, Other Peoples, Other Customs: World Ethnography and Its History (New York, 1972), 1–73. Lewis and Clark would have understood the modern desire for accuracy but not the idea of impartiality. Only rarely did they assume an air of cool detachment and scientific objectivity in their dealings with Native peoples. Disinterested observation was the furthest thing from their minds. Because the captains were confident of their own cultural superiority, they never doubted the wisdom of judging Indians by white standards. For Lewis and Clark, every observation was also a judgment. Just read their descriptions of the feisty Teton Sioux or the sharp Chinook traders and those judgments come through. Or listen to Sergeant Patrick Gass talk about the Mandan practice of feeding buffalo skulls and then damn the Indians for their foolish superstition.[7]Gass, Journal, 81-82. But the captains’ confidence did not become swaggering arrogance—something that cannot be said for those who came later. Fortunately, the explorers’ cultural biases did not prevent them form asking the right ethnographic questions. Equally fortunate, they had the good sense to write down many Indian answers, including many that seemed bewildering at the time.

Questions for Indians

Questions are the engines of intellect and the expedition was powered by a carefully designed question motor. The ethnographic question list Lewis and Clark took west with them had an evolutionary history all its own, and we should take a look at it to see just how seriously Jefferson regarded this part of the expedition.

Thomas Jefferson loved questionnaires. He used them to explore new areas of knowledge and then to organize what he had learned. His only published book, Notes on Virginia, was written in response to a questionnaire and retained the question and answer form on its chapters.[8]William H. Goetzmann, Exploration and Empire The Explorer and the Scientist in the Winning of the American West (New York, 1966), 5; Donald D. Jackson, Thomas Jefferson & the Stony Mountains … Continue reading Jefferson’s instructions to Meriwether Lewis are a series of interlocking questions ranging from mineralogy to medicine. The ethnography questions cover nearly every aspect of Indian life, including languages, customs, occupations, diseases, and morals.

Where did those very precise questions come from? The traditional answer has always been that they reflected Jefferson’s life-long fascination with Indian cultures. But there is something else going on here. There was more than one mind behind the expedition’s Indian questions. Early in 1803 Jefferson began to write friends both in and out of government asking their aid and advice for his western venture. Late in February he wrote three Philadelphia scientists, Caspar Wistar, Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, and Dr. Benjamin Rush, asking each to prepare some thoughts “in the lines of botany, zoology, or of Indian history which you think most worthy of inquiry & observation.”[9]Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Smith Barton, 27 February 1803; Jefferson to Caspar Wistar, 28 February 1803; Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, 28 February 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 16-19.

Questions from the Cabinet

Even before his consultants submitted their questions, Jefferson began instructions. By mid-April, 1803 he was ready to circulate it among certain cabinet members who were asked for their comments and criticisms. The remarks of Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin focused on western geography and the future expansion of the United States. Later in his career Gallatin made major contributions in collecting and systematizing Indian material. Just how much he had to do with framing expedition Indian questions is unknown.[10]“Albert Gallatin to Jefferson,” 13 April 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 32–34. This judgment must be modified if it can be determined that Gallatin had a major role in formulating some … Continue reading On the other hand, the reply from Attorney General Levi Lincoln clearly influenced Jefferson’s thinking. This important member of Jefferson’s official family has not gotten much attention from students of the expedition. Lincoln was a good New England lawyer, a skillful Republican politician, and he understood that the expedition served many purposes. Lincoln’s 17 April 1803 letter to Jefferson suggests that the early instructions draft he saw contained very little about Indians. To remedy this deficiency, Lincoln urged Jefferson to include questions about tribal religions, native legal practices, concepts of property ownership, and Indian medical procedures. Although Jefferson was already well acquainted with smallpox inoculation, it appears that Lincoln was the first to suggest that Lewis take some cowpox matter along to administer to Indians. The Attorney General’s suggestions were of major importance although, to be honest, he made them more out of political expediency than scientific curiosity. Lincoln was very sensitive to Federalist opposition to the journey, and he realized the administration would need to justify the expedition on the high ground of science if it failed.[11]Levi Lincoln to Jefferson, 17 April 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 35.

Levi Lincoln’s Questions

Levi Lincoln’s comments sharpened Jefferson’s focus on Indians. That focus was further enlarged and refined in May 1803 when Dr. Benjamin Rush presented Lewis with a detailed list of ethnographic queries. In 1774 Rush had offered a long paper at the American Philosophical Society titled “Natural History of Medicine Among the Indians of North America.” That paper presented Rush’s thoughts on all physical aspects of Indian life from diet and hygiene to sexual performance and pregnancy.[12]Benjamin Rush, Medical inquiries and observations, vol. I (Philadelphia, 1794), 9–77. See also Stephen J Kunitz, “Benjamin Rush on Savagism and Progress,” Ethnohistory, 17 (1970), … Continue reading That same wide range of interests was evident in the list Rush prepared for the expedition. The list was divided into three sections with medical concerns predictably taking first place. Under the heading “Physical history & medicine” Rush proposed twenty separate questions. He asked the explorers to record Indian eating, sleeping, and bathing habits as well as native diseases and remedies. He wanted to know when Indians married, how long children were breast fed, and how long they lived. Rush even urged the captains to find time to check Indian pulse rates morning, noon, and night both before and after eating!

Benjamin Rush’s Questions

Rush’s interests went well beyond mere medicine, encompassing Indian customs and values as well. The second part of Rush’s list included four questions touching on crime, suicide, and intoxication. His third sections probed Native American worship practices, sacred objects, and burial rituals. Like so many other European and American scientists, Rush was fascinated by Indian religions. Moreover, he believed as did many of his contemporaries that studies of Indian languages and religious ceremonies might prove or disprove a very old and persistent notion about the origin of Native Americans. A widespread academic theory held that Indian peoples might constitute one of the lost tribes of the children of Israel. If the Mandan were misplaced Welshmen, why not see if there were any Jewish Indians in the West.[13]Benjamin Rush, “Questions to Merryweather Lewis before he went up the Missouri, 17 May 1803,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 50. This list was passed to Jefferson in a letter from Lewis dated … Continue reading

Jefferson’s Final List

By June 1803 Jefferson had before him all the suggestions from fellow scientists and government officials. He also had the confidential message to Congress he had delivered in January which justified the expedition in terms of extending the Indian trade. He could also draw on instructions written for the abortive Michaux expedition a decade before.[14]Thomas Jefferson, “Message to Congress—Confidential, 18 January 1803,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 10-13; “Jefferson to André Michaux,” 30 April 1793, in Jackson, ed., … Continue reading Sometime during June, Jefferson synthesized these documents into the final draft of instructions for the expedition—instructions that now contained detailed questions in seventeen areas of Indian life and culture. [The instructions] are a milestone in history of exploration. The Indian questions cover everything from language and law to trade and technology. The expedition was to record what Indians wore, what they ate, how they made a living, and what they believed in. In short, Jefferson told Lewis: “You will therefore endeavor to make yourself acquainted, as far as a diligent pursuit of your journey shall admit, with the names of the nations & their numbers.”[15]Thomas Jefferson, “Instructions to Lewis, 20 June 1803,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 62–63, quote at 62.

Jefferson’s Western Visions

Before we look at how the captains carried out their ethnographic assignment in one place, we need to stop for a moment to ask why Jefferson wanted Lewis and Clark to gather so much technical information. Weren’t they already wearing too many hats? Had Jefferson’s lofty expectations lost touch with reality? Not at all. His reasons for turning two Army officers into part-time ethnographers were central to the many purposes of the journey. “The Commerce,” he wrote, “which may be carried on with the people inhabiting the line you will pursue, renders a knolege of those people important.”[16]Ibid., 62. Jefferson knew that fur traders and other eager entrepreneurs needed to know about future markets and sources of supply. In modern marketing terms, Jefferson was seeking “demographic” and “psychographic” data to help American merchants size up potential customers. To steal a line from the musical “Music Man,” if you want to be a good salesman, “you’ve got to know the territory.”

But there was something else behind Jefferson’s requirement that the captains be ethnographers—something beyond the vision of a rising fur trade empire. Lewis and Clark were sent to build another empire—the empire of reason, the kingdom of knowledge. Like his friends at the American Philosophical Society, Jefferson wanted the expedition to make a major contribution towards the scientific understanding of North America. That is what the President was talking about when he described the venture as a “literary expedition.”[17]Carlos Martinez de Yrujo to Pedro Cevallos, 2 December 1802, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 4. See also “Lewis’s British and French Passports” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 19–20 for … Continue reading Literary in this context means scientific. Jefferson wanted his explorers to advance the frontiers of learning by naming the Indian nations as well as labeling the nations of plants and animals. A serious, scientific concern for the human geography of the West impelled Jefferson to give the captains an ethnographic assignment.

Finally, and not to be overlooked, there was Jefferson’s vision of the future of North America. Jefferson believed that accurate information about Indians was essential in order to shape a peaceful tomorrow for both peoples. That desire for fact to replace fiction about Native Americans was nothing new in Jefferson’s mind. From boyhood on he had a passionate interest in things Indian. “In the early part of my life,” he wrote, “I was very familiar with the Indians, and acquired impressions of attachment and comiseration for them which have never been obliterated.”[18]Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 11 June 1812, in Lester J. Cappon, ed., The Adams-Jefferson Letters (Chapel Hill, 1959), 307. Jefferson’s fascination with Indian life was part boyish curiosity and part scientific inquiry, all bound up in the optimistic notion that if Native Americans gave up their traditional “savage” ways and adopted a white “civilized” lifestyle, both peoples could enjoy the continent in peace. “Acquire what knolege you can of [their] state of morality, religion & information,” Jefferson instructed the captains.[19]Thomas Jefferson, “Instructions to Lewis, 20 June 1803,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 63. It was a Jeffersonian fundamental that if we knew each other more fully, we would treat each other better. Ethnography could make government policy better informed and more humane. With an optimism based more on Enlightenment faith than American reality, Jefferson assumed that a benevolent government would then use that knowledge to civilize and Christianize Indians. Whether or not Native Americans would welcome the blessings of European civilization was of course another matter entirely.

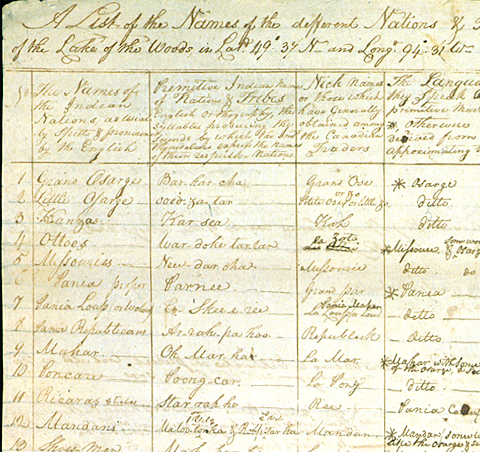

In Clark’s spreadsheet there are 14 more columns to the right of this detail, and 40 more lines below it. The overall dimensions of the seven sheets of letter paper pasted together are approximately 35″ by 28″. Transcribed below is the title, header row, and row 46. The rows and columns have been transposed to fit the constraints of a web page, and the captains’ remarks are placed below the table.—Ed.

A List of the Names of the different Nations & Tribes of Indians Inhabiting the Countrey on the Missourie and its Waters, and West of the Mississippi (above the Missourie) and a line from its head in Latd. 47° 38′ N. & Longt. 95° 6′ W. to the N W extremity of the Lake of the Woods, in Latd. 49° 37′ N. and Longd. 94° 31′ W. and Southerley & Westerley, of a West line from the Said Lake of Wood, as far as is known Jany. 1805. Expressive of the Names, Language, Numbers, Trade, water courses & Countrey in which they reside Claim & rove &c. &c. &c.

| a. The Names of the Indian Nations, as usially Spelt and pronounc’d by the English | Chipaways |

| b. Primitive Indian names of Nations & Tribes, English orthography, the syllables producing the Sounds by which the Inds themselves express the Names of their respective Nations | Oo-chi-pa-wau |

| c. Nick names or those which have Generally obtained among the Canadian Traders | Souteau |

| d. The Language they Speak if primitive marked*, otherwise derived from & approximating to | *Oo he-pawau |

| e. Nos. of Villages | 1 |

| f. Nos. of Tents or Lodges of the roveing Bands | [blank] |

| g. Number of Warriours | 400 |

| h. The probable Number of Souls of this Numbr. deduct about ⅓ ⅓ generally | 1600 |

| i. The Names of the Christian Nations or the Companies with whome they Maintain their Commerce and Traffick | British N W. Co. |

| j. The places at which the Traffick is usially Carried on | near their Village |

| k. The estimated Amount of Merchindize in Dollars at the St. Louis & Mickilimackanac, prices for their Anual Consumption | 12,000 |

| l. The estimated amount of their returns, in Dollars, at the St. Louis & Michilimacknac prices— | 16000 |

| m. The Kind of pelteries & Robes which they Annually supply or furnish | Beaver Otter, racoon fox Min[k] Deer & B Bear Skins & Martens |

| n. The defferant kinds of Pelteres, Furs, Robes Meat Greece & Horses which each Could furnish for trade | Beaver, otters, racoon, fox, Mink, Deer & B. Bear Skins & Martens |

| o. The place at which it would be mutually advantageous to form the principal establishment in order to Supply the Several nations with Merchindize. | head of Mississippi or at Red lake (Sandy Lake) |

| p. The Names of the Nations with whome they are at War/td> | Sioux (or Darcotas) (Saukees, Renars, and Ayouwais) |

| q. The names of the Nations with whome they maintain a friendly alliance, or with whome they may be united by intercourse or marriage | all the tribes of Chipaways and the nations about the Lakes & Down the Missippi |

| r. The particular water courses on which they reside or rove | in an Island in Leach Lake (formed by the Mississippi river) |

| s. The Countrey in which they usially reside, and the principal water Courses on or near which the Villages are Situated, or the Defferant Nations & tribes usially rove & Remarks | a village in a lake near the head of the Mississippi and an expansion of the Same Called Leach, they own all the Countrey West of L. Superor & to the Sous line— wild rice which is in great abundance in their [country] raise no Corn &c. |

Chippeways, of Leach Lake. Claim the country on both sides of the Mississippi, from the mouth of the Crow-wing river to its source, and extending west of the Mississippi to the lands claimed by the Sioux, with whom they still contend for dominion. They claim, also, east of the Mississippi, the country extending as far as lake Superior, including the waters of the river St. Louis. This country is thickly covered with timber generally; lies level, and generally fertile, though a considerable portion of it is intersected and broken up by small lakes, morasses and swamps, particularly about the heads of the Mississippi and river St. Louis. They do not cultivate, but live principally on the wild rice, which they procure in great abundance on the borders of Leach Lake and the banks of the Mississippi. Their number has been considerably reduced by wars and the small pox. Their trade is at its greatest extent.[20]Moulton, Journals, 388–89; 439–40.

Mandan Information

To see how the captains implemented Jefferson’s directives, to watch the explorers as ethnographers in action, I thought we might look at their activities during the winter of 1804–5. The Fort Mandan winter produced a wealth of material: journal entries, maps, the still-lost vocabularies, the very important “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” and valuable parts of the recollections William Clark gave Nicholas Biddle in 1810. This first winter in the field provided the captains with a superb on-the-job training program in ethnography. The techniques they devised and the information they obtained served them well for the rest of the voyage.

Lewis and Clark began their ethnographic work at Fort Mandan by simplifying and streamlining Jefferson’s original instructions. Long before coming to their winter quarters, the explorers realized they would have neither the time nor the language abilities to ask all of Jefferson’s Indian questions. The “Estimate of the Eastern Indians” gives us some clues to what questions the captains selected for their special attention.[21]The “Estimate of the Eastern Indians” is printed in Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, VI: 81–113. With some changes it was first published in Thomas Jefferson, “A Statistical View … Continue reading Drafted by the captains during the winter, the “Estimate” was a massive effort to organize and compare data on nearly fifty tribes and bands. In concept and design, it was as scientific as expedition ethnography ever got. Lewis and Clark would never again try anything as intricate and comprehensive. The nineteen questions used as an organizing structure for the “Estimate” show us what now seemed important to the explorers. Their highest priorities for each Indian group included tribal name, location, population, languages, and potential for American trade. Questions about religious traditions or cultural values were dropped from the official list. This did not mean that expedition ethnographers were unwilling to record that sort of data; the journals are filled with random notes about creation myths, migration legends burial practices, and sacred rituals. The Lewis entries on the Lemhi Shoshones are models of the ethnographer’s art.[22]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 3:3–44. What it does mean is that the captains very sensibly recognized their limitations during the Mandan winter and decided to use what time they did have to gather material on the externals of Indian life. They described how Indians looked but did not give any systematic attention to native souls and psyches. The captains would leave the quest for the interior of the Native American universe to others—to the likes of George Catlin and Prince Maximilian. Lewis and Clark’s commitment to the externals of Indian life can be seen in their coverage of native architecture. While the expedition record features fine descriptions of the outsides of teepees, earth lodges, and plank houses, that same record has very little about the insides of those structures.

Four Techniques

How did the expedition gather data during the Mandan winter? All of those puzzle pieces did not fall easily into the captains’ hands. The ethnographic record was the result of patient, persistent labor. The expedition used four different techniques to gather information. First, the captains directly questioned both Indians and whites, often at great length. Second, they collected objects—everything from Arikara corn to a Mandan buffalo skin painting—that represented important aspects of Indian life.[23]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:280-282. Third, the explorers reported what they could conclude from first-hand observation. Occasionally, information was obtained a fourth way. Some expedition members were able to gain their knowledge quiet personally by accepting the Indians’ invitation to participate in a hunt, a game, or a ceremony.

Of the four techniques, interviews yielded the most valuable information. Since the fort was within easy walking distance from the two Mandan villages, the captains had more Mandan informants than Hidatsa ones. Scores of Mandan men and women visited the fort for all sorts of reasons, but the most welcome guests were the following: Posecopsahe (Black Cat) chief of Ruptáre village, Big White (Sheheke) chief of Mututahank village, Little Raven (Kagohhami) a part-Arikara and second chief of Mututahank, Big Man (Ohheenar) an adopted Cheyenne and Coal (Shotaharrora) an adopted Arikara. It was very important that these chiefs and “considerable men” be courted and closely questioned. For generations chiefs and elders had served as tribal historians, committing to memory a whole body of past experience and tradition.[24]Alfred W. Bowers, Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization (Chicago, 1950), 94. Without the help of these men, the Lewis and Clark ethnographic record would have been both meager and unreliable. Of the two principal Mandan chiefs, Black Cat was the most valued by the captains. Meriwether Lewis characterized Black Cat as a man of “integrety, firmness, inteligence and perspicuety of mind.”[25]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:256. The chief made at least seventeen visits to the fort, some lasting many days. During these visits Black Cat often related “little Indian aneckdts [anecdotes].”[26]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:224–225. But like the Arikara traditions Clark dismissed as not worth mentioning, the pieces of Mandan history and belief shared by Black Cat were not recorded in the journals. Later in the voyage, when the captains had sharpened their ethnographic skills, they would now and then take time to preserve that sort of priceless detail.

Hidatsa Information

If there were plenty of Mandan informants, there were far fewer from the Hidatsa villages. Several factors limited the expedition’s access to Hidatsa information. Some Hidatsa chiefs, including the powerful Le Borgne or One Eye, were away on winter hunts for long stretches of time. More important, there was real suspicion and hostility among the Hidatsa, especially in Le Borgne’s village, about the intentions and behavior of the captains. Many Hidatsa were alarmed by expedition weapons and the size of Fort Mandan. Some elders resented what they called the captains’ “high-sounding language” while several warriors were angered by the explorers’ boasts about American military might. Le Borgne once bragged that if his warriors ever caught the Americans on the open plains they would make quick work of them. Such tensions, often fueled by Mandan-inspired rumors, kept many Hidatsa away from the fort and made the Indians reluctant to entertain the captains at the Knife River villages.[27]Elliott Coues, ed., New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest: The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry the Younger and of David Thompson, 3 vols. (New York, 1897), 349–350; Charles … Continue reading

The simple fact was that Lewis and Clark desperately needed Hidatsa information. The captains knew that unlike the Mandan, Hidatsa raiding parties ranged far west to the Rockies. Hidatsa informants could provide knowledge valuable not only for the second year of expedition travel but essential for its ethnographic assignment.[28]Coues, ed., New Light, 344; Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 6:91. The few important Hidatsa sources included Tatuckcopinreha, chief of the little Awaxawi village, and his neighbor the Awatixa chief Black Moccasin.[29]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:212. On occasion Tatuckcopinreha related “many strange accounts of his nation” but Clark chose to record only the bare outlines of recent Awaxawi migrations.[30]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:270–271. Notably absent for most of the winter were any Hidatsa-proper from Le Borgne’s village. It was not until the end of the winter that their awesome chief One Eye paid court at Fort Mandan. While the Hidatsa contacts were few, they did yield significant information. From those sources Lewis and Clark learned about the size and locations of the Crow, Flathead Salish, Shoshone, and Blue Mud (Nez Perce) Indians.[31]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 6:111. Without Hidatsa cooperation, however grudgingly given, there would have been substantial gaps in the Indian “Estimate.”

Information from Others

Throughout the winter there were other important contacts with Indians who were neither Mandan nor Hidatsa. Black Cat brought the Assiniboine band chief Chechank (the Old Crane) to talk with the captains, thereby expanding the explorers’ knowledge of northern trade routes. There were also a number of Cheyennes in the Mandan villages who perhaps filled the captains in on tribes to the West and Southwest. And of course there was Sacagawea, whose Shoshone contribution is simply impossible to verify. It seems more likely that whatever Lewis and Clark knew about the Shoshone came from Hidatsa sources.[32]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:221,233.

In all these talks the central problem was language translation. Charles Mackenzie, a North West Company trader who lived in Black Moccasin’s village during the Mandan winter, left some vivid impressions of those translation difficulties. Mackenzie recalled watching the captains struggle to record an Hidatsa vocabulary in which each word had to pass through a cumbersome translation chain stretching from a native speaker through Sacagawea, Toussaint Charbonneau, René Jusseaume and on to the captains. Heated arguments between the various translators were frequent, slowing the whole process and worrying many Indians. The way Mackenzie remembered it, as “the Indians could not well comprehend the intention of recording their words, they concluded that the Americans had a wicked design on their country.”[33]Mackenzie, “Narrative,” in Masson, ed., Lew Bourgeois, 1:336–337.

Language Barriers

Fortunately the captains had no such language barriers in their interviews with white traders living in the Indian villages around Fort Mandan. While their specific ethnographic contributions cannot always be traced in the expedition record, it is plain that men like Jusseaume, Charbonneau, Mackenzie, François-Antoine Larocque, and Hugh Heney provided much material for the Indian “Estimate” and Clark’s 1805 map of the western part of North America. The captains were especially impressed with the knowledge and experience of Nor’Wester Hugh Heney. They questioned him closely about Upper Mississippi tribes and the many Sioux bands.[34]Francois-Antoine Larocque, “The Missouri Journal, 1804-1805,” in Masson, ed., Les Bourgeois, 1:238. A fragment of a map based on Heney’s information is in Ernest S. Osgood, ed., The … Continue reading Heney’s imprint is on the Sioux and Chippewa [Ojibwe] sections of the “Estimate.” Other North West Company men like Larocque and Mackenzie offered their personal observations on the Assiniboine and the Cree. Despite his unsavory reputation, René Jusseaume did have the kind of first-hand Indian information the captains needed. Some of the most valuable comments in the journals about Mandan beliefs and inter-tribal relations came from Jusseaume.[35]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:220.

All this interviewing, translating, and observing produced accurate data about the names, numbers, and locations of Indians from the western Great Lakes to the Continental Divide, and from the Canadian Plains to north Texas. What the captains wanted, at least during the Mandan winter, was a kind of statistical geography of the tribes they had already met, those yet to be encountered, and those who might influence United States Indian policy. That is what the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians” really is—a limited but practical document for government agents and fur traders. Only later, after they were surer of their ethnographic skills, did Lewis and Clark get beyond counting Indian heads and locating villages to record more intimate details of native life.

Ethnographic Contributions

To evaluate Lewis and Clark’s ethnographic contributions, we need to ask three related questions. First, what did the expedition ethnographers see, understand, and accurately record? The captains and the other journalists excelled at setting down village locations, analyzing inter-tribal relations, and describing weapons, food, clothing, and many other material objects. Whether you want to know what an Arikara earth lodge looked like or how a Shoshone compound bow was made or the shape of a Chinook canoe, it is all vividly described in the expedition record. But, secondly, we also need to ask what the expedition saw, recorded, but did not understand. During that long Mandan winter the explorers encountered many things well beyond their own cultural experience. The Mandan buffalo calling ceremony, with its open sexuality, was one such event. Several expedition men obligingly took part in the ritual, and their experiences enabled William Clark to write a remarkably detailed description of the rite. Clark realized that the ceremony was undertaken to attract the buffalo and guarantee a successful hunt.[36]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:245. See also Annie H. Abel, ed., Tabeau’s Narrative of Loisel’s Expedition to the Upper Missouri (Norman, 1939), 197. But the American explorer simply could not fathom how sexual relations between old men or white men and the wives of younger Indians could bring the buffalo closer and ensure a good hunt. Clark did not understand that northern Plains cultures assumed that sexual intercourse was like a pipeline that could transfer spiritual power from one person to another. Old men had that special power and, as Clark himself noted, “the Indians say all white flesh is medisan.”[37]Osgood, ed., Field Notes, 172. Giving their wives to old men or white strangers was a way aspiring young men could appropriate powerful spirit forces for themselves.[38]Edward M. Bruner, “Mandan,” in Edward H. Spicer, ed., Perspectives in American Indian Culture Change (Chicago, 1961), 217; Alice B. Kehoe, “The Function of Ceremonial Sexual … Continue reading Nothing in his cultural heritage prepared William Clark to comprehend this, but he did have the good sense to make an accurate record of the ritual anyway. And it is equally important to remember that William Clark was not prudish about this. He wrote his account in plain English. It was that proper Philadelphian Nicholas Biddle who put Clark’s forthright words into more genteel Latin!

Finally, whenever we examine expedition ethnography we need to ask what Lewis and Clark did not see. Because it was the wrong time of year, they did not witness the awesome Okipa. Because many essential aspects of native life were culturally invisible to most white outsiders, the captains did not note the clans and age-grade societies that gave structure to Upper Missouri Indian life. Because some objects were hidden form all strangers, the explorers did not see the sacred bundles and the rituals surrounding them. Lewis and Clark never saw the interior of the Mandan and Hidatsa universe. That universe—the amalgam of moral and spiritual values that made Indians Indian—was simply beyond the explorers’ horizon. Seeing that they saw so much so well, we ought not to fault them for failing to catch the interior vision.

The Fort Mandan winter was a time for Lewis and Clark to serve out their apprenticeships in ethnography. By the time they got to the Shoshone, they were journeymen well on the way to becoming masters. From Fort Mandan on, the captains continually refined their collection techniques and sharpened their observation skills. Compare the entries written at Fort Mandan with those at Fort Clatsop to see how well the captains had learned their ethnographic trade. By the end of the journey they had indeed named the nations and so much more. Because Lewis and Clark carried out their ethnographic assignment with such skill, a central part of the past of North America and all her peoples will never die. We are the richer for what they did.

Notes

| ↑1 | For the original article, see on our sister site James P. Ronda, “”The Names of the Nations”: Lewis and Clark as Ethnographers,” We Proceeded On, November 1981, vol. 7 no. 4 available online at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol7no4.pdf#page=12. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, 4th Ed. (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1842), 2:139. |

| ↑3 | Verne F. Ray and Nancy O. Lurie, “The Contributions of Lewis and Clark to Ethnography,” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 44 (1954), 358–370. |

| ↑4 | Thomas Jefferson, “Instructions to Lewis, 20 June 1803,” in Donald D. Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 1783–1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana, 1978), 62. |

| ↑5 | Martha W. Beckwith, Mandan-Kidatsa Myths and Ceremonies (New York, 1937), 18; Patrick Gass, A Journal of the voyages of a Corps of Discovery (Pittsburgh, 1807; reprinted, Minneapolis, 1958), 79–80; “The Nicholas Biddle Notes,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 502, 520, 531; Reuben G. Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1804-1806, 8 vols. (New York, 1904–1905), 1:205, 221, 264, 272-274; Milo M. Quaife, ed., The Journals of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Sergeant John Ordway (Madison, 1916), 159. |

| ↑6 | Wendell H. Oswalt, Other Peoples, Other Customs: World Ethnography and Its History (New York, 1972), 1–73. |

| ↑7 | Gass, Journal, 81-82. |

| ↑8 | William H. Goetzmann, Exploration and Empire The Explorer and the Scientist in the Winning of the American West (New York, 1966), 5; Donald D. Jackson, Thomas Jefferson & the Stony Mountains (Urbana, 1981), 25–26. |

| ↑9 | Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Smith Barton, 27 February 1803; Jefferson to Caspar Wistar, 28 February 1803; Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, 28 February 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 16-19. |

| ↑10 | “Albert Gallatin to Jefferson,” 13 April 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 32–34. This judgment must be modified if it can be determined that Gallatin had a major role in formulating some of the questions William Clark copied in a long list sometime early in 1804. See William Clark, “List of Questions,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 157–161. |

| ↑11 | Levi Lincoln to Jefferson, 17 April 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 35. |

| ↑12 | Benjamin Rush, Medical inquiries and observations, vol. I (Philadelphia, 1794), 9–77. See also Stephen J Kunitz, “Benjamin Rush on Savagism and Progress,” Ethnohistory, 17 (1970), 31–42. |

| ↑13 | Benjamin Rush, “Questions to Merryweather Lewis before he went up the Missouri, 17 May 1803,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 50. This list was passed to Jefferson in a letter from Lewis dated 29 May 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 52. |

| ↑14 | Thomas Jefferson, “Message to Congress—Confidential, 18 January 1803,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 10-13; “Jefferson to André Michaux,” 30 April 1793, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 669–672, especially 670 where the language is clearly influential for the Lewis instructions. |

| ↑15 | Thomas Jefferson, “Instructions to Lewis, 20 June 1803,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 62–63, quote at 62. |

| ↑16 | Ibid., 62. |

| ↑17 | Carlos Martinez de Yrujo to Pedro Cevallos, 2 December 1802, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 4. See also “Lewis’s British and French Passports” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 19–20 for similar language. |

| ↑18 | Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 11 June 1812, in Lester J. Cappon, ed., The Adams-Jefferson Letters (Chapel Hill, 1959), 307. |

| ↑19 | Thomas Jefferson, “Instructions to Lewis, 20 June 1803,” in Jackson, ed., Letters, 63. |

| ↑20 | Moulton, Journals, 388–89; 439–40. |

| ↑21 | The “Estimate of the Eastern Indians” is printed in Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, VI: 81–113. With some changes it was first published in Thomas Jefferson, “A Statistical View of the Indian Nations inhabiting the Territory of Louisiana and the Countries adjacent to its northern and Western boundaries,” American State Papers; Class II, Indian Affairs, I (1806), 705–743. |

| ↑22 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 3:3–44. |

| ↑23 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:280-282. |

| ↑24 | Alfred W. Bowers, Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization (Chicago, 1950), 94. |

| ↑25 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:256. |

| ↑26 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:224–225. |

| ↑27 | Elliott Coues, ed., New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest: The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry the Younger and of David Thompson, 3 vols. (New York, 1897), 349–350; Charles Mackenzie, “The Missouri Indians: A Narrative of four Trading Expeditions to the Missouri, 1804–1805–1806,” in L. R. Masson, ed., Les Bourgeois De La Compagnie Du Nord-Ouest, 2 vols. (Quebec, 1889–1890), 1:330–331, 385; Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:227, 249. |

| ↑28 | Coues, ed., New Light, 344; Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 6:91. |

| ↑29 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:212. |

| ↑30 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:270–271. |

| ↑31 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 6:111. |

| ↑32 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:221,233. |

| ↑33 | Mackenzie, “Narrative,” in Masson, ed., Lew Bourgeois, 1:336–337. |

| ↑34 | Francois-Antoine Larocque, “The Missouri Journal, 1804-1805,” in Masson, ed., Les Bourgeois, 1:238. A fragment of a map based on Heney’s information is in Ernest S. Osgood, ed., The Field Notes of Captain William Clark (New Haven, 1964), 324. |

| ↑35 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:220. |

| ↑36 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:245. See also Annie H. Abel, ed., Tabeau’s Narrative of Loisel’s Expedition to the Upper Missouri (Norman, 1939), 197. |

| ↑37 | Osgood, ed., Field Notes, 172. |

| ↑38 | Edward M. Bruner, “Mandan,” in Edward H. Spicer, ed., Perspectives in American Indian Culture Change (Chicago, 1961), 217; Alice B. Kehoe, “The Function of Ceremonial Sexual Intercourse Among the Northern Plains Indians,” Plains Anthropologist, 15(1970), 99–103; Roy W. Meyer, The Village Indians of the Upper Missouri The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras (Lincoln, 1977), 79–80. |