The following is an extract from We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation.[1]James J. Holmberg, “William Clark, York, and Slavery,” We Proceeded On, August 2020, Volume 46, No. 3. The full article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol46no3.pdf.—KKT, ed.

The Search at Sugar Loaf Rock

In the afternoon of 4 June 1804, William Clark decided to investigate the purported occurrence of lead in the vicinity of a rather unique prominence he named “Mine Hill,”[2]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:276. William Clark journal quotations for June 1804 are … Continue reading but which is known today as Sugar Loaf Rock. This feature, located in northwestern Cole County upstream of Jefferson City between present-day Workman Creek and Meadows Creek, is a rather anomalous tower of middle to late Ordovician-age St. Peter Sandstone in the midst of the early Ordovician-age Cotter-Jefferson City Dolomite.[3]Michael A. Siemens, Bedrock Geologic Map of the Hartsburg 7.5′ Quadrangle, Boone and Cole Counties, Missouri, Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Missouri Geological Survey, … Continue reading Unlike the geologic formations the expedition encountered along the Mississippi River, these rocks were considerably older and part of a continent-sized paleodepositional setting now referred as the Great American Carbonate Bank.[4]The Great American Carbonate Bank is a sequence of primarily carbonate rocks deposited in relatively shallow seas on and surrounding the Laurentian paleocontinent during the Cambrian to earliest … Continue reading

Exceptionally pure quartz (crystalline silica) sand filled in a large solution cavity in the Cotter-Jefferson City Dolomite some fifteen to twenty million years[5]Derived from interpretations of Raymond L. Ethington, John E. Repetski, and James R. Derby, “Ordovician of the Sauk Megasequence in the Ozark Region of Northern Arkansas and Parts of Missouri … Continue reading after the dolomite was deposited. Those sands formed the St. Peter Sandstone, which proved to be more erosion-resistant over time; thus, it emerged to form a chimney-shaped prominence as the more soluble dolomite eroded around it. William Clark encountered the hill after walking about a mile “on the L Sd. thro a Charming Bottom of rich Land”[6]Moulton, ed., Journals, 2:275. on the south side of the river:

then I assended a hill of about 170 foot on the top of which is a Moun and about 100 acres of Land of Dead timber on this hill one of the party says he has found Lead ore. [Field Notes][7]Moulton, ed., Journals, 2:275.

assended a hill of about 170 foot to a place where the french report that Lead ore has been found, I saw no mineral of that description. [Notebook Journal][8]Moulton, ed., Journals, 2:276.

These journal entries suggest the report of lead ore did not occur during the expedition, but rather was an anecdote related to Clark by one of the engagés. This search for lead was important enough to document its lack of success, as Meriwether Lewis did in his “Summary view of the Rivers and Creeks”[9]Moulton, ed., Journals, 3:336. of the Missouri River (Codex O) composed sometime during the winter of 1804 to 1805 at Fort Mandan:

the Missouri washes the base of a high hill which is said to contain lead ore, our surch for this ore however pruved unsuccessfull and if it does contain ore of any kind, it must be concealed.[10]Moulton, ed., Journals, 3:341.

Missouri’s Central Mining District

The captains were not mistaken in reconnoitering this locale for lead occurrences. This area is on the northeast fringe of the Central Mining District, and although it would be the least productive of Missouri’s world-famous lead districts,[11]The others being the Tri-State District in southwest Missouri, which also includes parts of Kansas and Oklahoma, and the world-famous Southeast Missouri Lead District, including the Viburnum Trend, … Continue reading it contributed to Missouri’s standing as the leading producer of lead in the United States.[12]Cheryl M. Seeger, “History of Mining in the Southeast Missouri Lead District and Description of Mine Processes, Regulatory Controls, Environ-mental Effects, and Mine Facilities in the Viburnum … Continue reading It is not coincidental that lead (in the form of the mineral galena) along with zinc (in the form of the mineral sphalerite) and other metal-sulfide mineral deposits were so closely associated with the state-wide occurrences of limestone and dolomite, because those carbonate deposits were essential to the emplacement of these ores.[13]In an exceptionally complex tectonic and geochemical synergy that occurred after the deposition of the carbonate rocks, most of these Mississippi Valley-Type lead-zinc deposits were emplaced during … Continue reading

Lewis’ disappointment in failing to find lead at Mine Hill was probably tempered by the knowledge that he had energetically fulfilled Jefferson’s instructions earlier in St. Louis, in part by drawing upon one of the most useful books in the expedition’s traveling library, the 1774 edition of Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz’s The History of Louisiana.[14]Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, The History of Louisiana, or of the Western Parts of Virginia and Carolina: Containing a Description of the Countries that lie on both Sides of the River Missisipi: … Continue reading

Du Pratz’s Earlier Search

Detail: Area of Interest

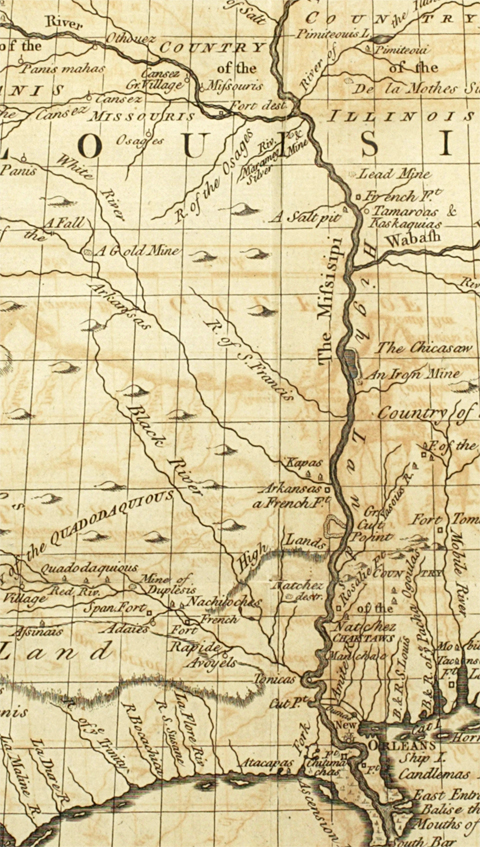

Courtesy The Library Company of Philadelphia. The full dimensions of this map as it appeared in the 1763 and 1774 editions are 11-7/16 inches high by 13-5/8 inches wide. The scale is 1:8,500,000.

Du Pratz’s 1774 map includes iron, salt, silver gold, and lead mines along both sides the Mississippi River below the mouth of the Missouri River.

Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz’s The History of Louisiana (1774) was originally published in French as Histoire de la Louisiane in 1758 (three volumes), but was translated into English in a two volume edition in 1763 and a single volume edition in 1774. Du Pratz, believed to be a Netherlands native who closely identified himself with the French, had some training in architecture and hydraulic engineering. Du Pratz spent the years between 1718 through 1734 in the lower Mississippi River valley running a plantation and engaging in other entrepreneurial ventures. The History of Louisiana can be read as a practical guidebook describing the land forms, climate, agriculture, natural resources, flora, and fauna of Louisiana, but the book is largely acclaimed for its perceptive, non-judgmental, and sympathetic observations of the Natchez Indian culture, ethics, and social organization prior to the obliteration of the Natchez by the French.[15]Joseph G. Tregle, Jr., ed., The History of Louisiana, Translated from the French of M. Le Page du Pratz (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 1975) [a facsimile reproduction of … Continue reading The fame of this particular volume in Lewis and Clark circles is based in part on the fact that it survived the transcontinental journey intact and was returned to its owner Benjamin Smith Barton. Lewis’ gracious inscription on the flyleaf (9 May 1807) thanks Barton for the four-year loan of the book.[16]The inscription is reproduced twice in Paul Russell Cutright, Contributions of Philadelphia to Lewis and Clark History (West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Philadelphia Chapter, Lewis and Clark Trail … Continue reading

For the most part, The History of Louisiana described the region’s economic geology and mineralogical resources in fairly general, but roughly serviceable, terms. For example, du Pratz discussed the occurrence of various minerals he encountered in his forays throughout the lower Mississippi River Valley, with an emphasis on clays, “plaster,” gypsum, pit-coal, salts, saltpeter, and stones for building.[17]Du Pratz, The History of Louisiana, 131, 138-139, 149, 159-160, 162, 164, 167, and 171-172. In addition, a map that accompanied The History of Louisiana, entitled “A Map of Louisiana, with the course of the Missisipi [sic], and the adjacent Rivers, the Nations of the Natives, the French Establishments and the Mines; By the Author of ye History of that Colony. 1757,” depicted locations of a salt pit and iron, lead, silver, and gold mines, by which du Pratz meant deposits and not necessarily active mining operations.

Du Pratz appeared to have particularly enjoyed searching for and discovering mineral ores, especially lead deposits. Upon completing a fruitful search for lead, he exclaimed, “I was highly pleased at this discovery, which was that of a lead-ore. I had also the satisfaction to find my perseverance recompensed; but in particular I was ravished with admiration, on seeing this wonderful production, and the power of the soil of this province, constraining, as it were, the minerals to disclose themselves.”[18]Du Pratz, The History of Louisiana, 147. Most intriguing for the purposes of ascertaining the source of Lewis and Clark’s inquiries regarding the mineral resources of Louisiana, du Pratz opined, “the land which lies between the Missisippi and the river St. Francis . . . contain several mines: some of them have been assayed; among the rest, the mine of Marameg, on the little river of that name . . . . There are some lead mines, and others of copper, as is pretended.”[19]Du Pratz, The History of Louisiana, 177. The St. Francis River, which debouches into the Mississippi River south of Memphis, Tennessee, roughly parallels the Mississippi River from northern Arkansas … Continue reading

Lewis’s Lead Specimens

Lead and Zinc in Calcite Matrix

(Galena and Sphalerite)

Photo by Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

“A very rare and unique combination specimen from the Viburnum Trend District [Southeast Missouri]. This showy, old-time specimen features glassy, jet-black bitumen (a “solid oil” or hydrocarbon material) scattered amongst a rich covering of lustrous, metallic-gray galena [lead] cubes and sphalerite [zinc] crystals on a vuggy, two-sided matrix of silicified limestone coating with tiny, contrasting, colorless calcite rhombs. The back even features a couple of quartz needles, as a highlight. Ex. George Feist Collection.”—Rob Lavinsky

Although Lewis and Clark may have found the mineralogical information in The History of Louisiana useful, to the extent it provided a preview of what the lands of the lower Missouri River Valley might contain, du Pratz’s identification of lead and other mines proximal to the St. Francis and Meramec Rivers may have prompted Lewis’ inquiries about the current status and production of the lead mining during the time he was in St. Louis making final preparations for the expedition. Lewis apparently circulated a census/survey form letter in early January 1804 to the leading merchants and citizens of St. Louis inquiring about populations, demographics, imports and exports, and natural resources, including specific questions involving lead and other mining operations:

11. What are your mines and minerals? Have you lead, iron, copper, pewter, gypsum, salts, salines, or other mineral waters, nitre, stone-coal, marble, lime-stone, or any other mineral substance? Where are they situated, and in what quantities found?

12. Which of those mines or salt springs are worked? and what quantity of metal or salt is annually produced?[20]Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:162.

These inquiries yielded at least fourteen donated mineralogical specimens that Lewis relayed to Jefferson on 18 May 1804, nine of which were “Specimens of led oar from the Mine of Berton, situate on the Marimec River, now more extensively wrought than any other led Mine in <Upper> Louisiana.”[21]Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:192. These samples of lead ore were presented by Nicholas Boilvin and Peter Chouteau. The Mine à Breton is not situated on the Meramec River, which has complicated the … Continue reading There is no mention of a “Mine of Berton” or more correctly the “Mine à Breton,” in The History of Louisiana because it was not until 1774 that François Azor dit Breton discovered rich lead deposits at a site approximately sixty miles southwest of St. Louis in the environs of present-day Potosi, Missouri.[22]Walter A. Schroeder, Opening the Ozarks: A Historical Geography of Missouri’s Ste. Genevieve District 1760-1830 (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2002), 284-285. According to … Continue reading

A year later, Lewis would enclose two additional Mine à Breton lead specimens in the shipment of minerals sent back East from Fort Mandan, a “Specimen of lead ore of Bertons mine on the Marimeg River” (Fort Mandan mineralogical specimen No. 27) and a “Specimen of the lead ore of Bertons’ mine on the Marrimic River Upper Louisiana” (Fort Mandan mineralogical specimen No. 29).[23]For details on the three separate mineral collections Meriwether Lewis assembled during the expedition, see John W. Jengo, “‘Specimine of the Stone’: The Fate of Lewis and Clark’s … Continue reading Why Lewis sent these specimens from the Upper Missouri is uncertain, given he had already provided Jefferson with nine essentially equivalent specimens in the aforementioned mineral shipment of 18 May 1804. The author speculates these additions were intended to compensate for not locating lead ore deposits along the lower Missouri River,[24]Of the “Mine River” (present day Lamine River) passed on June 8, 1804, Lewis wrote in his “Summary view” of another thwarted inquiry: “Mine river . . . derives … Continue reading including the unproductive 4 June 1804, exploration of Mine Hill.

Glossary

- Carbonate: sedimentary rocks composed primarily of minerals containing the carbonate ion; the two major types of carbonate rocks are limestone and dolomite.”

- Dolomite: rock composed of calcium-magnesium carbonate.

- Ordovician: A period of Earth’s geological history that began approximately 485.4 million years ago and ended approximately 443.8 million years ago.

- Paleodepositional: the physical, chemical, and biological environment associated with the deposition of particular types of sediments in the distant geologic past.

- Rhombs: rhombohedral or diamond-shaped crystals.

- Solution cavity: opening formed in carbonate rocks, such as limestone, where portions have been dissolved by naturally acidic percolating waters.

- Vuggy: with small, unfilled cavities.

Notes

| ↑1 | James J. Holmberg, “William Clark, York, and Slavery,” We Proceeded On, August 2020, Volume 46, No. 3. The full article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol46no3.pdf.—KKT, ed. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:276. William Clark journal quotations for June 1804 are from volume 2, by date. All Atlas citations in the ensuing text are from volume 1, by map number. |

| ↑3 | Michael A. Siemens, Bedrock Geologic Map of the Hartsburg 7.5′ Quadrangle, Boone and Cole Counties, Missouri, Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Missouri Geological Survey, OFM-2015-661-GS, 2015, scale 1:24,000. The Ordovician Period was approximately 490.9 to 443.4 million years (Ma) ago per Peter M. Sadler, Roger A. Cooper, and Michael Melchin, “High-Resolution, Early Paleozoic (Ordovician-Silurian) Time Scales,” Geological Society of America Bulletin, 121:5/6 (May/June 2009): 887-906. To determine the age dates or time gaps between various formations for this article, the author had to cross-reference numerous technical papers to determine which biostrati-graphic (fossil) zone a particular lithostratigraphic formation occupies, then correlate that biostratigraphic zone to a local North American chronostrati-graphic stage and series, then correlate that designation to age date charts that include international chronostratigraphic units with assigned global geo-chronological age ranges such as K.M. Cohen, S.C. Finney, P.L. Gibbard, and J.-X. Fan, The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) International Chronostratigraphic Chart v2019/05 (2013; updated May 2019), Episodes 36: 199-204. The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart has the Ordovician Period as occurring approximately 485.4 to 443.8 Ma ago. The cited age dates in this article are approximate because work continues on refining the boundaries of virtually every chronostratigraphic (rock) and geochronological (age) unit in the geological record. |

| ↑4 | The Great American Carbonate Bank is a sequence of primarily carbonate rocks deposited in relatively shallow seas on and surrounding the Laurentian paleocontinent during the Cambrian to earliest middle Ordovician periods when this enormous area (extending roughly 1,860 miles from present-day Nevada to Tennessee and 930 miles from present-day Texas to Minnesota) was located within 30 degrees of the paleoequator. See James R. Derby, Robert J. Raine, M. Paul Smith, and Anthony C. Runkel, “Paleogeography of the Great American Carbonate Bank of Laurentia in the Earliest Ordovician (Early Tremadocian): The Stonehenge Transgression,” 5-13, and William A. Morgan, “Sequence Stratigraphy of the Great American Carbonate Bank,” 37-82, in James Derby, Richard Fritz, Susan Longacre, William Morgan, and Charles Sternbach, eds., The Great American Carbonate Bank: The Geology and Economic Resources of the Cambrian-Ordovician Sauk Megasequence of Laurentia, AAPG Memoir 98 (Tulsa, Oklahoma: The American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 2012). |

| ↑5 | Derived from interpretations of Raymond L. Ethington, John E. Repetski, and James R. Derby, “Ordovician of the Sauk Megasequence in the Ozark Region of Northern Arkansas and Parts of Missouri and Adjacent States,” 275-300, and John F. Taylor, John E. Repetski, James D. Loch, and Stephen A. Leslie, “Biostratigraphy and Chronostratigraphy of the Cambrian-Ordovician Great American Carbonate Bank,” 15-35, in Derby, et al., eds., Great American Carbonate Bank. |

| ↑6 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 2:275. |

| ↑7 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 2:275. |

| ↑8 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 2:276. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 3:336. |

| ↑10 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 3:341. |

| ↑11 | The others being the Tri-State District in southwest Missouri, which also includes parts of Kansas and Oklahoma, and the world-famous Southeast Missouri Lead District, including the Viburnum Trend, Mine La Motte-Fredericktown, and the Old Lead Belt subdistricts, the latter from which Lewis would obtain samples while in St. Louis. |

| ↑12 | Cheryl M. Seeger, “History of Mining in the Southeast Missouri Lead District and Description of Mine Processes, Regulatory Controls, Environ-mental Effects, and Mine Facilities in the Viburnum Trend Subdistrict,” in Michael J. Kleeschulte, ed., Hydrologic Investigations Concerning Lead Mining Issues in Southeastern Missouri, U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5140, 2008, 5-33. |

| ↑13 | In an exceptionally complex tectonic and geochemical synergy that occurred after the deposition of the carbonate rocks, most of these Mississippi Valley-Type lead-zinc deposits were emplaced during later Paleozoic time, including during the late Mississippian (330 Ma) to middle Permian (265 Ma) tectonic plate collisions that formed the Ouachita Mountains. These intense tectonic events and continual uplifts resulted in high groundwater temperatures (75 to 200oC), a steep topographic gradient, and groundwater flow velocities conducive to the leaching of lead from older granite/rhyolite basement rocks and transport of these seawater-infused metal-enriched fluids northward into the host carbonate rocks in present-day Missouri. This process is technically referred as “topographically-driven gravitational fluid flow.” Geochemical mixing with other fluids and changes in pH allowed the metals to precipitate out of solution and either replace the carbonate rock or fill void spaces typically found in limestone and dolomite. For more details, see David L. Leach, Ryan D. Taylor, David L. Fey, Sharon F. Diehl, and Richard W. Saltus, “A Deposit Model for Mississippi Valley-Type Lead-Zinc Ores,” Chapter A of Mineral Deposit Models for Resource Assessment, U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010-5070-A, 2010, 52 p. |

| ↑14 | Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, The History of Louisiana, or of the Western Parts of Virginia and Carolina: Containing a Description of the Countries that lie on both Sides of the River Missisipi: With an Account of the Settlements, Inhabitants, Soil, Climate, and Products, Translated from the French of M. Le Page du Pratz; with some Notes and Observations relating to our Colonies, A New Edition (London, England: Printed for T. Becket, Corner of the Adelphi, in the Strand, 1774). |

| ↑15 | Joseph G. Tregle, Jr., ed., The History of Louisiana, Translated from the French of M. Le Page du Pratz (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 1975) [a facsimile reproduction of the 1774 edition]. It was the observations during the time du Pratz spent with the Natchez between 1720 and 1728 and his reporting of the Natchez Massacre of 1729 that have made The History of Louisiana an invaluable ethnological document. |

| ↑16 | The inscription is reproduced twice in Paul Russell Cutright, Contributions of Philadelphia to Lewis and Clark History (West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Philadelphia Chapter, Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, James-Allan Printing and Design Group, LLC, 2001, with site maps by Frank Muhly), 14, 24. Curiously, Cutright did not mention it was the 1774 edition Lewis borrowed. Donald Jackson surmised correctly back in 1959 that the captains were “most likely [using] the 1774 translation;” see Donald D. Jackson, “Some Books Carried by Lewis and Clark,” Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society 16 (October 1959): 9. |

| ↑17 | Du Pratz, The History of Louisiana, 131, 138-139, 149, 159-160, 162, 164, 167, and 171-172. |

| ↑18 | Du Pratz, The History of Louisiana, 147. |

| ↑19 | Du Pratz, The History of Louisiana, 177. The St. Francis River, which debouches into the Mississippi River south of Memphis, Tennessee, roughly parallels the Mississippi River from northern Arkansas into southeastern Missouri up to Farmington, Missouri. The Meramec River is located southwest of St. Louis. |

| ↑20 | Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:162. |

| ↑21 | Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:192. These samples of lead ore were presented by Nicholas Boilvin and Peter Chouteau. The Mine à Breton is not situated on the Meramec River, which has complicated the author’s efforts in determining the true attribution of these lead samples, but the mines were located in the Meramec River watershed by virtue of being adjacent to Mine à Breton Creek (now Breton Creek), a tributary of Mineral Fork, which flows into the Big River, a major tributary of the Meramec River. The various spellings of the Meramec River by Meriwether Lewis in the historical record (such as Marimec, Marimeg, and Marrimic) was another factor to reconcile in the author’s research. |

| ↑22 | Walter A. Schroeder, Opening the Ozarks: A Historical Geography of Missouri’s Ste. Genevieve District 1760-1830 (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2002), 284-285. According to Schroeder, Mine à Breton (also rendered as Mine au Breton) was also called Burton, or using Lewis’ spelling, Berton. |

| ↑23 | For details on the three separate mineral collections Meriwether Lewis assembled during the expedition, see John W. Jengo, “‘Specimine of the Stone’: The Fate of Lewis and Clark’s Mineralogical Specimens,” We Proceeded On, 31:3 (August 2005): 17-26. Any reference to a mineral specimen in the narrative prefaced by “Fort Mandan mineralogical specimen” refers to those minerals sent back East from Fort Mandan in April 1805 as outlined in Moulton, ed., Journals, 3:473-478. |

| ↑24 | Of the “Mine River” (present day Lamine River) passed on June 8, 1804, Lewis wrote in his “Summary view” of another thwarted inquiry: “Mine river . . . derives it’s name from some lead mines which are said to have been discoved on it, tho’ the local situation, quality, or quantity of this ore, I could never learn.” Moulton, ed., Journals, 3:342. |