Buffaloberry

Shepherdia argentea (Pursh) Nutt.

Location: On the Missouri River just below the Knife River, 7 July 2013. © by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

In the above photo, a sharp thorn stealthily waits for the unwary picker.

On 24 August 1804, the expedition passed a burning bluff known to history as the Ionia Volcano (see NE Nebraska Minerals), York killed an elk, and the captains are told of a nearby mysterious hill of little devils, Spirit Mound. Clark also described a berry that makes “delitefull Tarts:”

Great quantities of a kind of berry resembling a Current except double the Sise and Grows on a bush like a Privey, and the Size of a Damsen deliciously flavoured & makes delitefull Tarts, this froot is now ripe[1]The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark, Gary Moulton, ed., 2:504.

Range and Uses

S. argentea grows best in riparian zones in the high prairies of the Midwest from Nebraska to Alberta and Manitoba. It was known to the Native Nations, engagés, and St. Charles boatmen who lived and traveled within this range, but new to science.

For generations, people living within reach of the plant ate the fruit fresh and dried the berries for winter use. It was often added to rendered buffalo fat and dried, pounded jerky to form mixture known as pemmican.[2]Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 528. Additionally, the Blackfeet made a red dye and digested the berries as a mild laxative.[3]Alex Johnston, “Plants and the Blackfoot” Provincial Museum of Alberta: Natural History Occasional Paper No. 4, (1982), 64, University of Calgary Library, … Continue reading The Yankton Sioux sometimes served the berry in feasts to honor a girl reaching puberty.[4]Melvin R. Gilmore, “Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region” (Smithsonian Institution—Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report, Number 33, 1919), 106.

The plant’s cousin, the russet buffaloberry, Shepherdia canadensis, is common in valleys and sub-alpine forests throughout Montana.[5]Donald A. Schiemann, Wildflowers of Montana (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2005), 42; Gregory L. Tilford, Edible and Medicinal Plants of the West (Missoula, Montana: Mountain … Continue reading The bush is smaller and the berries are not as tasty and is sometimes called soapweed and soopalallie due to its flavor and concentration of the soap-like chemical saponin.[6]A. Scott Earle and James L. Reveal, Lewis and Clark’s Green World: The Expedition and its Plants (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003), 33. S. canadensis berries were a starvation food for the Blackfoot[7]Hellson, 105. and most-often eaten with non-traditional sugar added.[8]Moerman, 529. The Okanagan and Thompson people made alcoholic drinks from the fermented berries.[9]F. Perry, “Ethno-botany of the Indians in the Interior of British Columbia,” Museum and Art Notes 2, no. 2 (1952): 39 in Moerman, 528.

Picking the Fruit

To identify the silver buffaloberry in the wild, look for bright red berries and thorns. The best time to harvest is after the first frost when the berries will be their sweetest. Do be careful. Food historian Leandra Zim Holland warns:

Anyone unfamiliar with this thorny, spiky bush doesn’t know what effort this entailed. Old timers used to arm themselves in long sleeves and gloves, and take a blanket as a catch-all, and the baseball bat was used to batter the bush until the berries fell off. It was a hazardous occupation tangling with the spines, but the berries are worth it.[10]Leandra Zim Holland, Feasting and Fasting with Lewis & Clark: A Food and Social History of the Early 1800s (Emigrant, Montana: Old Yellowstone Publishing, 2003), 105.

Ethnobotanist Alex Johnston, gives the Blackfoot Old Man legend explaining why buffaloberries are beaten off the bush rather than picked by hand:

Old Man stood on the bank of a stream, looked down and saw red berries in the water. So he dived into the water but could not find the berries. He dove again and again and nearly drowned. Finally he became tired and lay down under a shady bush. Then, looking up, he saw the berries overhead. He became very angry, picked up a club, and beat the berry-bush until there was but one berry left. And that is the reason why people to this day beat buffalo berries from the bushes with sticks.[11]Johnston, 64.

New to Science

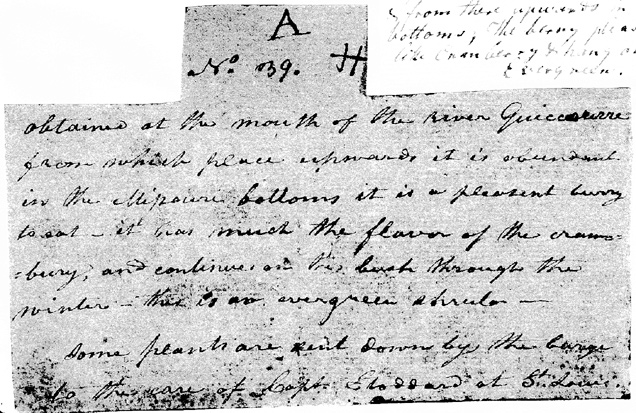

The observations from Lewis were more scientific than Clark’s gastronomic pursuits. On 4 September 1804 near the Niobrara River, he collected specimens. According to his herbarium specimen note, he also sent live plants from Fort Mandan to be cared for by Amos Stoddard. Lewis’s original note is still attached to one of the two herbarium sheets at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The note reads:

A No. 39. H[?] obtained at the mouth of the River Quiccourre from which place upwards it is abundant in the Missouri bottoms it is a pleasant burry to eat—it has much the flavor of the cranbury, and continues on the brush through the winter—this is an evergreen shrub—some plants are sent down by the barge to the care of Capt. Stoddard at St Louis. [12]Journals: Herbarium, 51.

Few of Lewis’s original specimen labels survive today. Many have been replaced with Frederick Pursh‘s copies of Lewis’s originals. It appears that Pursh rarely followed Lewis’s wording verbatim, often reducing the number of words used. For example, Pursh’s note for this specimen reads:

From the mouth of the Quiccourre & from there upwards in all the Missouri bottoms; The berry pleasant, acid like Cranberry & hang on all winter Evergreen.[13]Ibid.

Pursh re-arranged Lewis’s specimens into two sheets, the latter of which he took with him to England. There he used the specimen to identify the plant as argentea, placing it in the genus Hippophaë. Pursh’s sheet of Lewis specimens was eventually returned to Philadelphia and serves as the species’ lectotype—the specimen used to identify all subsequent descriptions.[14]James L. Reveal, Gary E. Moulton, and Alfred E. Schuyler, “The Lewis and Clark Collections of Vascular Plants: Names, Types, and Comments,” Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences … Continue reading Following Lewis and Clark’s botanical trail in 1811, Thomas Nuttall collected the plant and placed it in a new genus—Shepherdia after botanist John Shepherd (1765–1836).[15]Earle and Reveal, 32–33.

Clark’s Delightful Tart

On 1 October 1804, Clark repeated his gastronomical theme:

The Mandans Call a red berry common to the upper part of the Missouri Ăs-sáy the engages call the Same berry grease de Buff— grows in great abundance a makes a Delightfull Tart[16]Journals, 3:136.

Food historian, Leandra Holland provides the following recipe for buffaloberry tart:[17]Holland, 105.

To construct the pie is not difficult, although a person must have access to the berries. That is where the first and most difficult problem arises: picking them. It is a vicious, wickedly thorned bush that defies standard picking. A second variety, a more northerly bush, doesn’t have the thorns but grows a far more sour berry.

Constructing the tart requires two steps: the shell and the filling. Here follows a recipe that the Corps’ mess cooks could have made with provisions at hand. (The shell recipe generally follows a traditional short-pastry recipe such as listed in The Old West Baking Book, and the filling is from the author’s experience. Modern adaption of the shell would substitute ½ cup butter and ½ solid shortening for the lard, and ice water for “river water.”)

The Shell: Short Pastry

- 2½ C. flour

- ½ tsp. salt

- 1 C. Lard

- 4 T. cold (river) water

Blend flour and salt. Chill lard (in river). Add to flour by cutting in with two. Keep cutting and slowly add cold water. Roll out to ¼” thick. Note: It’s more crumbly texture than flaky. Shape for a 9″ tart.

Buffaloberry Filling

- 6 C. buffaloberries

- 1 C. sugar

- ¼ tsp flour

Mix berries, sugar, and flour; and fill pie shell. Cover with a pastry top if you have enough dough. Bake tart at 375° for 1 hour.

Notes

| ↑1 | The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark, Gary Moulton, ed., 2:504. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 528. |

| ↑3 | Alex Johnston, “Plants and the Blackfoot” Provincial Museum of Alberta: Natural History Occasional Paper No. 4, (1982), 64, University of Calgary Library, digitalcollections.ucalgary.ca/asset-management/2R3408TBKKXX?FR_=1&W=2154&H=1931; John C. Hellson, “Ethnobotany of the Blackfoot Indians,” National Museum of Man Mercury Series, no. 19 (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1974), 68, archive.org/details/ethnobotanyofbla0000hell. |

| ↑4 | Melvin R. Gilmore, “Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region” (Smithsonian Institution—Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report, Number 33, 1919), 106. |

| ↑5 | Donald A. Schiemann, Wildflowers of Montana (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2005), 42; Gregory L. Tilford, Edible and Medicinal Plants of the West (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 1997), 20 |

| ↑6 | A. Scott Earle and James L. Reveal, Lewis and Clark’s Green World: The Expedition and its Plants (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003), 33. |

| ↑7 | Hellson, 105. |

| ↑8 | Moerman, 529. |

| ↑9 | F. Perry, “Ethno-botany of the Indians in the Interior of British Columbia,” Museum and Art Notes 2, no. 2 (1952): 39 in Moerman, 528. |

| ↑10 | Leandra Zim Holland, Feasting and Fasting with Lewis & Clark: A Food and Social History of the Early 1800s (Emigrant, Montana: Old Yellowstone Publishing, 2003), 105. |

| ↑11 | Johnston, 64. |

| ↑12 | Journals: Herbarium, 51. |

| ↑13 | Ibid. |

| ↑14 | James L. Reveal, Gary E. Moulton, and Alfred E. Schuyler, “The Lewis and Clark Collections of Vascular Plants: Names, Types, and Comments,” Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 149 (29 January 1999), 46–47. |

| ↑15 | Earle and Reveal, 32–33. |

| ↑16 | Journals, 3:136. |

| ↑17 | Holland, 105. |