The Expedition at NeCus’ Village

For countless generations, human communities have called the Ecola Creek estuary home. Before the resort town of Cannon Beach, Oregon, emerged in the late nineteenth century, a Tillamook tribal village—NeCus’—sat along this tiny brackish bay where it crosses the sandy beach to the open sea. The Lewis and Clark Expedition journals provided a tantalizing but fragmentary glimpse of this community. Here, we share a wider view of this beachfront village and its significance before, during, and after the Corps of Discovery’s visit in January of 1806.

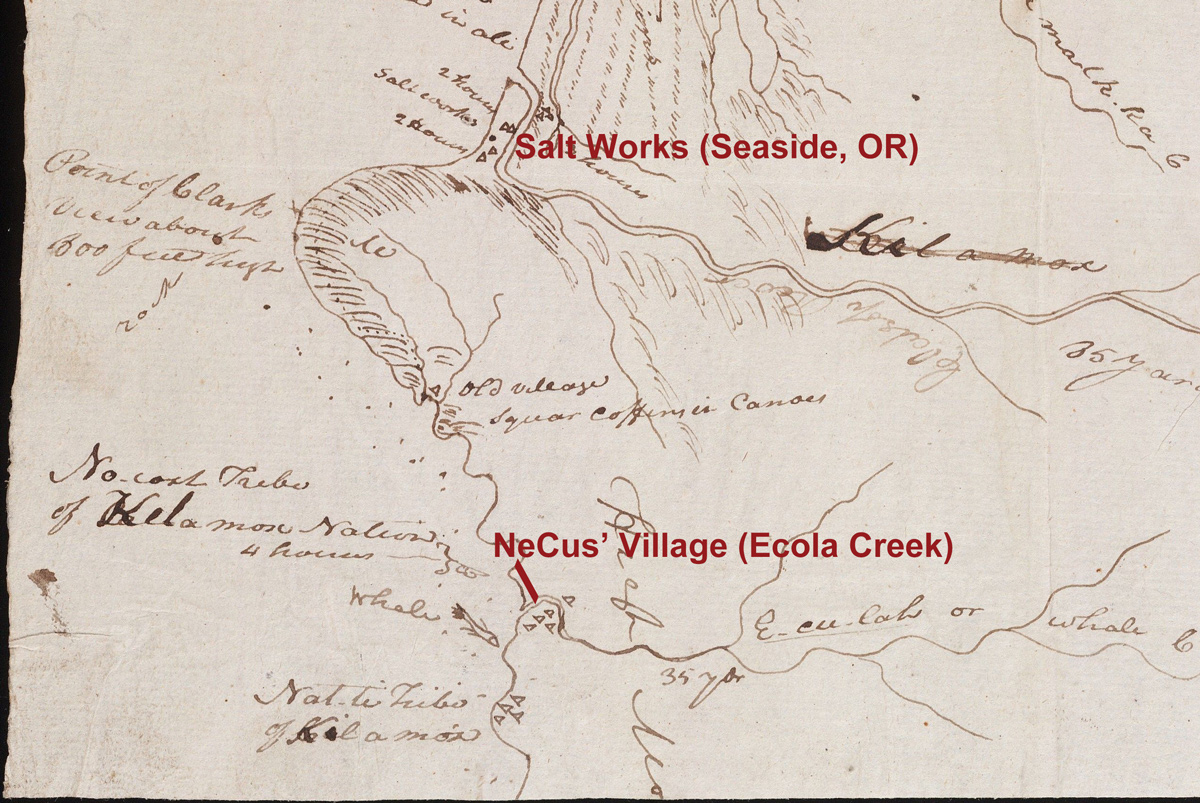

Figure 1

South of the Columbia Mouth (Detail)

by William Clark

Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, WA MSS 303.

Clark’s map noting the location of the “No-cost Tribe of Kil a mox Nation:” near the site of the beached whale (shown as a drawing). For a fuller description of this map, see Over Tillamook Head.

The journals offer the only detailed, firsthand written description of this Ecola Creek community. Encamped at Fort Clatsop through the winter of 1805–1806, Corps members had been living in close connection and actively trading with the resident Clatsop community and Chief Coboway (a.k.a. Comowool in the journals). In early January, Native traders brought whale meat and blubber to the fort. According to Lewis’ journal entry, dated 5 January 1806, this blubber was “not unlike the fat of Poark . . . very pallitable and tender.”[1]In Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 6:166. Low on provisions and eager to break up the redundancy of their winter diet, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark dispatched a party to obtain meat and blubber from villagers living near the beached whale. On 8 January 1806, embarking from the salt makers‘ camp near the Clatsop villages of Nakut’at and Neakawksi in modern-day Seaside, members of the Corps crossed Tillamook Head toward NeCus’ village, where the whale was beached.

Clark and twelve other Corps members including Sacagawea traveled southward on a well-established tribal trail over the Neaseu’su—an imposing headland, some 1,200 feet high, jutting more than two miles into the turbulent sea. Today it is called “Tillamook Head,” and sits within Ecola State Park. On their descent from the spectacularly scenic summit at “Clark’s Point of View,” the party passed an abandoned village full of burial canoes. From there, they proceeded to the bustling village at the mouth of Ecola Creek.[2]On these villages and trail networks, see, e.g., Douglas Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, Report to Oregon Heritage Commission, Salem, OR, 2005, 79–84; John P. Harrington, … Continue reading Here, at the village we now know as NeCus’, the Corps found the whale largely flensed, and residents unwilling to part easily with whale products. Though residents had their own names for this place, Clark dubbed the creek “Ecola,” the term for “whale” in the trade language of Chinuk wawa (Chinook Trade Jargon). Clark’s comments on the people and structures of NeCus’ village are brief but informative. Clark noted a “village of 5 Cabins on the Creek.”[3]Moulton, ed., Journals, 6:183. The texts from his journal entry and expedition map (Figure 1) suggest the principal village sat on the south bank of the estuary, with a single house on the north bank.

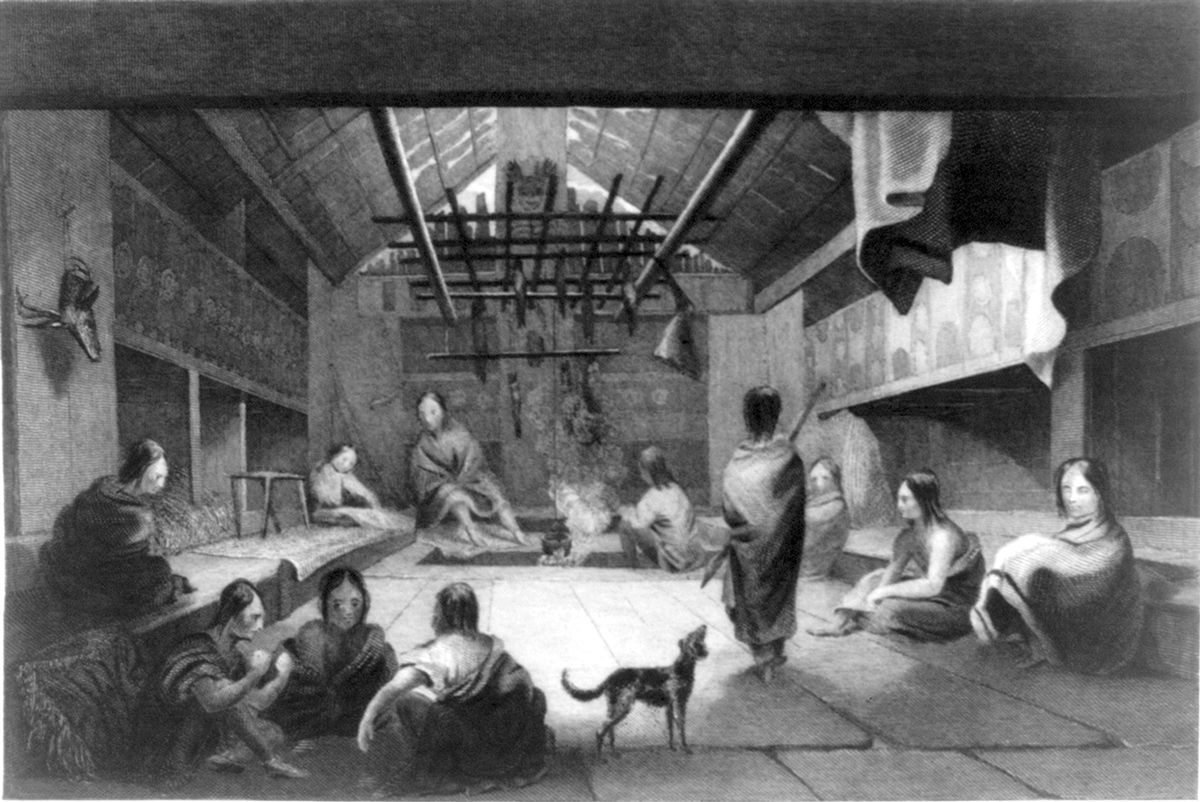

Figure 2

Chinook Indian Lodge, Opposite Fort George

Henry Warre (1819–1898)

From an original sketchbook owned by the American Antiquarian Society in Sketches in North America and the Oregon Territory (Imprint Society: Barre, Massachusetts, 1970), plate 45.

As described in Clark’s journal entries and other ethnographic accounts, the houses at NeCus’ village were of similar scale and design to the structure depicted here. Tongue Point can be seen center left, placing this Clatsop lodge at present-day Astoria. Many of the planks used in the construction of Fort Clatsop were ‘borrowed’ from empty lodges—see Clatsop Give and Take. In Warre’s sketch above, it appears boards have also been re-used from other structures.—KKT, ed.

Figure 3

Chinook Lodge

by Alfred.T. Agate (1812–1846)

Richard Dodson, engraver. From Vol. 4 of Wilkes’ Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition, during the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. Courtesy U.S. Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2001696058/ .

The interior of a Chinookan longhouse, as seen by the U.S. Exploring Expedition, led by Charles Wilkes, in the 1840s. The central excavated floor area—covered in woven mats—is a traditional center of social activity, ceremony, and food processing. Two tiers of platforms used for beds, sitting, and storage areas encircle a partially excavated floor with a central fire. Woven mats of cattail, rushes, cedar bark, and other plant materials serve as room partitions, tethered to poles, or as padding on sitting and bed areas.

Clark described houses that were “of the Same form of those of the Clatsops.” From the journals, alongside other ethnographic accounts, we know these houses resembled those common throughout the Tillamook world—with walls of split cedar planks chinked with lichen or moss, a rectangular floor plan, and a gabled roof (Figure 2). Chinookan houses had central floors dug into the ground and bench-like platforms used for sitting, sleeping, storage, and other purposes (Figure 3).[4]Moulton, ed., Journals, 6:184. These wide benches spanning each wall, roughly two feet above the floor, were likely lined with cedar planks. Mats woven from locally available cattails, rushes, and other plants were used as floor coverings and interior partitions.[5]Elizabeth Derr Jacobs, “Ethnographic Notes: Field Notebooks, Folklore, and Ethnography Based on Three Months’ Fieldwork among the Tillamook Salish, Garibaldi, Oregon,” Unpublished … Continue reading Clean sand, spread on the floor, was replaced frequently to keep floors clean. Firepits in the center of each room were surrounded by rock or split boards laid on their sides. In the dark of winter, torches of Sitka spruce or Douglas fir pitch provided additional illumination. Aligned to the waterfront, these longhouses served several functions: as living spaces, storage areas, meeting halls, and ceremonial venues. A longhouse could house twenty or more inhabitants, implying a village of perhaps a hundred or more at the time of Clark’s visit.[6]Jacobs, The Nehalem Tillamook; Jacobs, “Ethnographic Notes,” Folder 106:8:1; May Mandelbaum Edel, Lexical Notes, Field Notebooks, Lexical Files, Folklore Texts, Based on Fieldwork among … Continue reading

The “No-Cost Tribe of the Kil a mox Nation”

A Convenient StopoverSomething of the character and composition of NeCus’ can be inferred from the thin archaeological, ethnographic, and historical record.[7]Generalizable references to the culture, history, and worldview of the Native communities in the region can be found in diverse sources, from published works to archival accounts to “gray … Continue reading As Clark observed, the village at Ecola Creek sat within the traditional territory of the “Kil a mox Nation.” The villagers were indeed associated with the Nehalem (or northern) Tillamook, being Salish-speaking peoples who differed in language if not necessarily culture from the Clatsop and other Chinookan kin to the north.

While the NeCus’ village buzzed during Clark’s brief visit with non-resident tribal visitors gathered to harvest the beached whale, this gathering of multiple tribes speaking multiple languages was a common sight at the mouth of Ecola Creek. For NeCus’ village was a place where tribes met and shared food, trade goods, songs, and stories as people traveled north and south along the coast. The Tillamook and other tribal communities along Oregon’s coast passed through NeCus’ while traveling to and from the vast Chinookan villages such as Niak’ilaki (or Tlatcep, both meaning “pounded salmon place”—the origin of the name “Clatsop”) at the Columbia River’s mouth. Preeminent salmon fishing and trade centers, these Columbia River villages were prominent hubs of multi-tribal social, economic, and ceremonial life.

As a stopover point for travelers rounding Tillamook Head on these journeys, NeCus’ village was especially important. Tribal members of the last century mention this place as “an easy landing place . . . a stopping-over place at which the Tillamook Ind[ian]s in canoes headed for the Col[umbia] Riv[er] in April.”[8]Fuller in Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 471. This continued in the decades following the Corps’ visit: tribal elder Joe Scovell (1922–2014), for example, reported that his great-grandfather Chief Illga often stopped at NeCus’ when traveling between his village on Tillamook Bay and the fur trading post at Astoria to trade in the first half of the nineteenth century. Stopovers at this place were critical: paddling around Tillamook Head was long and arduous, requiring perhaps ten miles of paddling through exposed and rocky surf, so that many paddlers took a deserved rest at NeCus’ village before or after their trek. Canoe crews often found a break in the surf beside Haystack Rock—usually on the north face in the winter and the south in the summer, reflecting prevailing seasonal winds and currents. When the surf was too rough for safe canoe travel (likely the case during Clark’s visit), people instead traveled over the steep Tillamook Head trail.[9]Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 79–81.

Archaeological and ethnographic evidence tells us that NeCus’ village sat at a center for resource procurement—a place where salmon-bearing streams, forests rich in elk and berries, and offshore rocks abounding in shellfish and other marine foods all converged in one place.[10]Melissa Darby, Archaeological Investigations at the Ne-Cost Village Site, 35CLT77, on the Northern Oregon Coast. SHPO #06-0909. Unpublished Archaeological Site Form (Salem: Oregon State Historic … Continue reading But what of the whale, the object of the Corps’ visit? Available accounts suggest that whale was a prized but relatively rare component of the traditional Tillamook diet. Men did hunt whales by canoe at sea—a process that apparently involved mortally wounding an animal at locations where prevailing currents would carry it to shore. Clark reported that, by the time his party arrived at NeCus’, the resident Tillamook and visitors from other villages had already harvested most of the beached whale’s meat and blubber, presenting Clark with a largely skeletonized animal and little hope of restocking their dwindling food stores. His 8 January 1806 journal entry reads, “the Whale was already pillaged of every valuable part.”[11]Melissa Darby, Archaeological Investigations at the Ne-Cost Village Site, 35CLT77, on the Northern Oregon Coast. SHPO #06-0909. Unpublished Archaeological Site Form (Salem: Oregon State Historic … Continue reading Clark estimated the whale to be roughly 105 feet long, suggesting it was a blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus)—less common than other species in the Tillamook hunting tradition perhaps, but the only whale to reach such proportions on this coast. At NeCus’ village, the party found the community busily rendering the blubber[12]Moulton, ed., Journals, 6: 183.—a scene not entirely uncommon here into the nineteenth century. In 1853, settler Warren Vaughan reported seeing a large number of tribal members near NeCus’ butchering a different “captured” whale, rendering the blubber in their canoes—placing hot rocks in water and ladling rendered oil from the water’s surface.[13]Warren Vaughan, An Early History of Tillamook, 1851–52, Unpublished ms. (Tillamook, OR: Tillamook County Pioneer Museum, n.d.), 29. Likewise, Louie Fuller, a Tillamook man living at Siletz in the 1940s, reported: “My father told me what I never got to see, that [Tillamooks] put water in a small canoe and then put whale meat & hot rocks & in just a little while the whale meat would be boiled & ready to eat.”[14]In Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 416.

Clark’s term for the creek at NeCus’, “Ecola Creek,” was immediately forgotten in common local use, the name “Elk Creek” persisting instead. Still, the moniker “Ecola” returned with the Sesquicentennial Lewis and Clark commemorative events of 1955–1956. Through the twentieth century, the term was reapplied to the creek and associated landmarks, as well as the Oregon state park just north of Cannon Beach.[15]Lewis A. McArthur, Oregon Geographic Names, 6th ed. (Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1992), 279–80.

Lessons from the Name of NeCus’

Figure 4

Ecola Creek

© 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

For more, see Ecola by Air.

Figure 5

Silverweed

Argentina anserina pacifica (syn. Potentilla anserina)

© 2009 by Walter Siegmund. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Named places reported in ethnographic archives provide clues to life in NeCus’ village before Lewis and Clark. The place-name Neshyetskawen or Nes’yetska’ away, “place with yetska roots,” refers to the edible roots of the silverweed “that grow in the tideland” adjacent to the village at Ecola Creek. A staple of the Nehalem-Tillamook people and others along the Northwest Coast, Ecola Creek was the only place to find silverweed roots in quantity between Seaside and Nehalem Bay.

Based on his interpretation of Native pronunciation, Clark recorded the name No-cost or Ne-cost for NeCus’ village. Regrettably, the term has not been found elsewhere and the name’s meaning remains ambiguous. Based on a review of available Nehalem-Tillamook linguistic information, the closest match appears to be “NeCus'”—”place of the low tide” or “place of the receding tide.” [16]Laurence C. Thompson and M. Terry Thompson, “Nehalem Tillamook Dictionary,” Unpublished ms. in author’s possession. Clark and his contemporaries commonly added “t” or … Continue reading Popularized in the last decade, this spelling has become the official name of the Cannon Beach city park at the former village site, and appears in National Park Service media relating to the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.[17]See, e.g., https://www.nps.gov/places/necus-park.htm.

Even if the exact term remains unclear, this name seems a remarkable fit: the site is linked in important ways to historical events involving low or rapidly outgoing tides. In summer, the Ecola Creek estuary water levels become “perched” for months at a time as sand bars form at its mouth, aided by gentle surf and sediment-rich currents that flow southward from the Columbia River. In fall, the level of the water plunges abruptly—often within a few hours—as early-season storms bring high surf and runoff. This pattern is idiosyncratic and would have been strikingly apparent to NeCus’ residents. While the association is speculative, it is consistent with other naming traditions in the region.

Yet another, even more compelling possible explanation for the name revolves around oral traditions of tsunamis at NeCus’. One of only a few recoverable, ancient stories of the village describes a tide that abruptly receded as prelude to a massive tsunami wave. One version was reported by tribal elder Alexander Duncan as part of a 1930s Works Projects Administration Federal Writers Project oral history study conducted by Cecile Adams. While most of Adams’ notes are lost, her younger half-brother Paul See recalled frequently rereading Duncan’s account, which describes a pre-contact tsunami at NeCus’ with remarkable geological accuracy:

Alexander Duncan . . . . He told my sister this story . . . . His story goes that there were a number of villages there on the beach just south of Tillamook Head. And one day, the great Sahalie Tyee [Creator] took the ocean away. And so, all the young women of the villages were sent down to gather as many of the mussels as they could get. And while they were down there, Sahalie brought the ocean back and they were all drowned. It was a terrible disaster for the Natives, and so the story goes, the mothers sit on the beach for weeks afterwards, crying for their lost daughters.[18]In Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 80–81.

There are hints that the destruction was brought about by the hubristic squabbling of arrogant chiefs, whom the Creator turns into rocks that appear like huge inverted “baskets” in the sea—around Chapman Point just north of NeCus’—before rapidly pulling back the tide and unleashing the tsunami. Apparently in reference to this story, twentieth-century elders such as Clara Pearson recalled the enduring place-name “Dahon’tatch” or “the baskets” in reference to these rocks.[19]Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 454; Jacobs, “Ethnographic Notes,” Folder 106:6:64. In light of the apparent weight and prominence of this story cycle, it is conceivable that the village where the event occurred retained the name “NeCus'” or “place of the receding tide.”

Other named places provide clues to the nature of life at this village before the time of Lewis and Clark. A few place-names were reported in ethnographic archives for different areas close to the village. They include Neshyetskawen or Nes’yetska’away, “place with yetska roots,” a reference to the edible roots of the silverweed Argentina anserina (Figure 5) “that grow in the tideland” adjacent to the village at Ecola Creek.[20]Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 416. This plant was a staple of the Nehalem-Tillamook people and others along the Northwest Coast.[21]Nancy J. Turner and Harriet V. Kuhnlein, “Two Important ‘Root’ Foods of the Northwest Coast Indians: Springbank Clover (Trifolium wormskioldii) and Pacific Silverweed (Potentilla … Continue reading Elder Louie Fuller reported of this plant that “it is yellow when cooked. They boil it and if they have lots, they heat rocks and earth-oven bake it.”[22]In Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 416. With its broad, salt-tolerant meadows abounding in Pacific silverweed, Ecola Creek was the only place to find such roots in quantity between Seaside and Nehalem Bay. Indeed, this place-name had a Clatsop equivalent. During an 1899 Oregon Historical Society research expedition to the coast, directed in part by Clatsop attorney (and Chief Coboway grandson) Silas Smith, the expedition recorded Clatsop terms for “a place near Elk [i.e., Ecola] Creek where an edible plant, the Eckutlipatli, was found” called “Ne-ahk-li-paltli”—suggesting that the plant’s significance at this place was widely appreciated.[23]Horace S. Lyman, “Indian Names,” The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 1:3 (1900): 316–26.

Kóshtawah (Maggie Adams)

Born in Cannon Beach, apparently at NeCus’ village, early in the nineteenth century and close to the time of the Corps of Discovery’s visit, Maggie Adams (Kóshtawah) later married Nehalem-Tillamook Chief Illga and became the matriarch of the last Tillamook community on their traditional lands, near today’s Garibaldi, Oregon.

In the history of NeCus’ village, the visit of the Corps of Discovery portended the riveting changes ahead. Residing so close to the mouth of the Columbia, with its steady traffic in European and American ships from 1792 onward, the Tillamook and Clatsop people suffered frequent epidemics of smallpox, malaria, and other shipborne diseases that reached a crescendo by the early 1830s, reducing tribal populations to perhaps ten percent of what Lewis and Clark had beheld. Soon, early Euro-American settlement in Astoria and Clatsop Plains, and federal refusal to ratify the “Tansy Point Treaties” of 1851, forced most survivors to relocate to Northwest reservations and other tribal communities. Together, these impacts reduced the Native American population of the northern Oregon coast to a minute fraction of its pre-contact totals, only some four decades after Clark and his party visited NeCus’.

Detailed information regarding NeCus’ village and its residents during this period is thin. While the village was Tillamook, Clatsops appear to have been intermarried with the community across recoverable time. During the time of epidemics and colonization, displaced Clatsops seem to have grouped here with growing frequency.[24]Charles E. McChesney, ed., Rolls of Certain Indian Tribes in Oregon and Washington (Fairfield, WA: Ye Galleon Press, 1906 [1969]); National Anthropological Archives, Photograph Notes-Tillamook, … Continue reading From the period following Lewis and Clark’s visit, we know only a few names of NeCus’ residents, and all of them are of combined Tillamook and Clatsop ancestry. One was Kóshtawah, later christened Maggie Adams—born at NeCus’ village around the time of the Corps’ visit, and daughter of a Clatsop father and Tillamook mother (Figure 6). Adams was also a niece to Chief Tostom, the chief who succeeded Coboway (Lewis and Clark’s omnipresent Clatsop host). The exact date of her birth is disputed; published estimates date Maggie Adams’ birth to around 1800, though it is likely she was born shortly after the Corps of Discovery visited her village. She seems to have lived at NeCus’ during her younger years only, as her life was dramatically and abruptly disrupted by inter-ethnic conflicts on the Northwestern frontier.[25]National Anthropological Archives, Photograph Notes—Tillamook, compiled by Marguerite Stasek. One descendant recalls,

During a conflict between the Shoshones and the white settlers, Maggie’s parents had been killed, and she was taken to a convent near Yamhill. Her people searched for her and when they found her, convinced those in charge to return her to them . . . . Maggie had received some education at the convent and [later, when she returned] she created quite a stir because she wore clothing and cooked like white men.[26]Clifford M. Scovell, “The History of Harry William Scovell,” Unpublished ms. (Tillamook, OR: Tillamook County Pioneer Museum, n.d.). See also Adams Family files, Unpublished files … Continue reading

After leaving the convent, Maggie moved to Tostom’s village at the Columbia River mouth, soon meeting and marrying the presiding Tillamook chief from Tillamook Bay, Chief Illga. With growing pressures to abandon both Clatsop and Tillamook villages, the couple removed to Tillamook Bay, eventually settling at the small tribal community at Hobsonville. Like his fellow Tillamook leader Chief Kilchis, Illga was noted for his compassion toward early white settlers who arrived at the coast with inadequate provisions.[27]Obituary-Illga (Adams)-Tillamook Indian, Bay City Examiner, 10 October 1890. In 1875, a Grand Ronde missionary visiting the community, Adrian Joseph Coquet, baptized the couple as “Maggie” and “Adam.” And together, they became a highly respected nucleus of the last tribal community that remained on Nehalem-Tillamook lands, even as many tribal members removed to reservation communities at Grand Ronde, Siletz, and Quinault, or to non-reservation communities in distant locations. According to elder Clara Pearson’s accounts in the 1930s, the couple were widely seen as “high class . . . happy . . . good and righteous [and] kind to everybody.”[28]Clara Pearson in Jacobs, Ethnographic Notes, Folder 106. In the Hobsonville settlement, Maggie and Illga raised three daughters who, with their own children, became the core of the last enduring Tillamook village on the coast, disbanded only around World War II.[29]Joe Scovell in Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 55–63; Douglas Deur, “Hobsonville Indian Community,” Oregon Encyclopedia. Digital resource. (Portland: Oregon Historical Society, … Continue reading Most of what is written about Nehalem-Tillamook culture is derived from interviews conducted with residents of this remarkably resilient tribal community.[30]Notable examples include Elizabeth Derr Jacobs, Nehalem-Tillamook Tales (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1990 [Eugene: University of Oregon Press, 1959]); Jacobs, The Nehalem Tillamook; … Continue reading

Though Maggie, her immediate family, and others left NeCus’ when Maggie was young, the village limped along for a few decades more. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was clearly dilapidated, reflecting the dramatic population declines across the region. By this time, only intermittent and seasonal occupation occurred at NeCus’. Non-Native travelers’ accounts offered thin hints of tribal occupation. Settler Warren Vaughan visited the mouth of Ecola Creek and stayed at the remnants of NeCus’ in 1852, describing his taking refuge from the rain in “a rude hut shelter that probably some Indians had made.”[31]Vaughan, An Early History, 8. Eleven years later, Clatsop County settler Preston Gillette suggested that a single family lived in what is today Cannon Beach—a Native family by the name of Gervais (often spelled “Jarvey”), apparently residing in what remained of NeCus’ village.

The Gervais Family

The Gervais family held chiefly significance in both the Clatsop and Nehalem-Tillamook worlds. Edward Gervais (ca. 1836-1909) was the son of a French-Canadian Astor Company employee, Joseph Gervais, and Chief Coboway’s daughter, Yiamust. Like many children of mixed families during the fur trade, he spent part of his youth in the French Prairie community near modern-day Gervais, named in his father’s honor. He returned to the coast to marry Nish-Slush or “Nancy”—daughter of Chief Esahtin from Nehalem Bay; and for many years, the couple lived in Cannon Beach intermittently, hunting, fishing, gathering, and sustaining connections with this place of enduring tribal significance.[32]Betty Obrist, in Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 27–28. Though the couple eventually moved to Nehalem Bay, they also stayed seasonally in the emerging tourist town of Seaside, joining other tribal members in the enclave called “Indian Place.”[33]Douglas Deur, “The Making of Seaside’s ‘Indian Place’: Enduring and Contested Native Spaces on Oregon’s North Coast,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 117 no. 4 (2016): … Continue reading At times, hoteliers hired them to tell tribal stories to Seaside tourists—especially at the opulent Seaside House hotel, founded by rail magnate William Holladay.[34]Mrs. John [Mary] Gerritse, “Gerritse family-Interview transcription,” Unpublished ms. (Seaside, OR: Seaside Historical Society Museum collections, n.d.). Often in popular accounts, Nancy was identified as the “last Nehalem Indian,” though her descendants continued to live in the region and identify as Native people.

Following the Gervais family’s departure, the NeCus’ site fell into ruin and was reoccupied for non-Native uses. Yet for Native families, NeCus’ village remained an important landmark, despite the dispersal of its resident Native people. Descendants of village residents continued to visit, work, and sometimes live in the larger community of Cannon Beach even as the village site was overrun by new, non-Native development. When, in 1892, hotelier Henry Logan built the first wagon road to Cannon Beach, he hired two tribal members, reportedly “Indian Louie” and “Klutche,” to blaze the trail. Alexander Duncan, source of the tsunami narrative, was later hired to improve the passageway and became the first official “roadmaster” of this route.[35]A.W. Norblad, in Jack Fosmark, “Elk Creek Toll Road,” Unpublished ms. (Seaside, OR: Seaside Historical Society Museum collections, n.d.); Samuel Dicken, Pioneer Trails on the Oregon Coast … Continue reading Moreover, key Cannon Beach settlers had Clatsop tribal ties: Jacob E. Brallier (1862–1954) and his brother Frank Brallier (1866–1949), for example, were homesteaders who had claims on the southern end of Cannon Beach. The eventual subdivisions of their land helped kick start the burgeoning tourist town of Cannon Beach. Both were stepsons of Charlotte Smith, a granddaughter of Clatsop Chief Coboway, who married Jacob and Frank’s father after their mother’s death.[36]John Brallier, “Interview with Mr. John Brallier,” Unpublished ms. (Seaside, OR: Seaside Historical Society Museum collections, 1957). The two brothers were raised in close proximity to Coboway’s daughter, Celiast, spoke Clatsop in their home, and though lacking direct Clatsop ancestry, recounted many stories in the Clatsop language. Members of this family still reside and run retail shops in the Cannon Beach area.[37]Harriet Munnick, “Interview with J. Brallier,” Unpublished ms. (Astoria, OR: Clatsop County Historical Society collections, n.d.); Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 25–26, 39.

NeCus’ village continues to be a place of sharing and learning today. Here, archaeologist Kendall McDonald, author Douglas Deur, and cultural resource specialist Shawn Steinmetz (Confederated Tribes of Umatilla Indian Reservation) present to students of the joint National Park Service-Portland State University Archaeology Field School regarding the history and ongoing research of NeCus’.

The Site Today

In recent times, tribal people with ties to Cannon Beach have continued to visit and sometimes participate in social, educational, and ceremonial events in the area. They also took part in the 1955–1956 Lewis and Clark Sesquicentennial and 2005–2006 Bicentennial commemorations in the community. Since those events, the descendants of NeCus’ residents have reconnected with this important place in many ways. While the tribal history of Cannon Beach has yet to be fully written, it is clear that tribal members—including a small number of descendants who have direct ties to the NeCus’ village—continue to recognize this as a place of importance.

When members of the Corps of Discovery visited NeCus’ village in January of 1806, they recorded details of village life that remain largely absent in other historical sources. They witnessed a village abuzz with Native American resource harvests, social gatherings, and visitors from communities north and south along the coast—a scene likely repeated for unknown generations before the Corps’ arrival, which continued for a few generations to follow. Based on many lines of evidence—including the memories of tribal elders and the larger corpus of tribal oral tradition, we can augment William Clark’s observations and assumptions about Native life in the village considerably. Many lives, many personal narratives, were linked to NeCus’. Clearly, several residents were associated with Coboway and other figures known to readers of the journals. But the available record remains tantalizingly vague, reflecting the dramatic changes on the northern Oregon coast in the years after Clark’s account and the suddenly catastrophic turn in Native lives. Brought to the brink of collapse by introduced diseases and displacement, the NeCus’ population plummeted by the mid-nineteenth century. Neither Clark nor his Native American hosts at NeCus’ village could have anticipated the abrupt changes that would displace this village and bring another, very different kind of settlement to the banks of Ecola Creek. Yet despite the transformation, certain things remain: the site of NeCus’ village, a smattering of archival accounts, and the oral traditions and enduring attachments of tribal members—revisiting and revering this special place into the present day.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the elders of the recent past, especially Joe Scovell and Betty Obrist, for kindly sharing their knowledge of NeCus’ and its residents. We also wish to thank the elders of an earlier generation, including Clara Pearson and Louie Fuller, for entrusting their knowledge of the Oregon coast with past researchers. A portion of Dr. Deur’s research on NeCus’ was funded in part by the National Park Service and the Oregon Heritage Commission.

Notes

| ↑1 | In Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 6:166. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | On these villages and trail networks, see, e.g., Douglas Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, Report to Oregon Heritage Commission, Salem, OR, 2005, 79–84; John P. Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” Reel 20, John Peabody Harrington Papers (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives, 1942–1943), 425. |

| ↑3 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 6:183. |

| ↑4 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 6:184. |

| ↑5 | Elizabeth Derr Jacobs, “Ethnographic Notes: Field Notebooks, Folklore, and Ethnography Based on Three Months’ Fieldwork among the Tillamook Salish, Garibaldi, Oregon,” Unpublished ms. (Seattle: Jacobs Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, n.d.), Folder 106:8; Elizabeth Derr Jacobs, The Nehalem Tillamook: An Ethnography, edited by William Seaburg (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2003), 70–73. |

| ↑6 | Jacobs, The Nehalem Tillamook; Jacobs, “Ethnographic Notes,” Folder 106:8:1; May Mandelbaum Edel, Lexical Notes, Field Notebooks, Lexical Files, Folklore Texts, Based on Fieldwork among the Tillamook Salish, Oregon. Unpublished docs. English translations by May Edel, Larry and Terry Thompson, and D. Deur. (Seattle: Jacobs Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, 1931). |

| ↑7 | Generalizable references to the culture, history, and worldview of the Native communities in the region can be found in diverse sources, from published works to archival accounts to “gray literature” reports; consider Franz Boas, “Chinook Texts,” Bulletin of the U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, No. 20 (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology, 1894); Jacobs,” Ethnographic Notes;” Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook;” Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence. |

| ↑8 | Fuller in Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 471. |

| ↑9 | Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 79–81. |

| ↑10 | Melissa Darby, Archaeological Investigations at the Ne-Cost Village Site, 35CLT77, on the Northern Oregon Coast. SHPO #06-0909. Unpublished Archaeological Site Form (Salem: Oregon State Historic Preservation Office, 2006). |

| ↑11 | Melissa Darby, Archaeological Investigations at the Ne-Cost Village Site, 35CLT77, on the Northern Oregon Coast. SHPO #06-0909. Unpublished Archaeological Site Form (Salem: Oregon State Historic Preservation Office, 2006). |

| ↑12 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 6: 183. |

| ↑13 | Warren Vaughan, An Early History of Tillamook, 1851–52, Unpublished ms. (Tillamook, OR: Tillamook County Pioneer Museum, n.d.), 29. |

| ↑14 | In Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 416. |

| ↑15 | Lewis A. McArthur, Oregon Geographic Names, 6th ed. (Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1992), 279–80. |

| ↑16 | Laurence C. Thompson and M. Terry Thompson, “Nehalem Tillamook Dictionary,” Unpublished ms. in author’s possession. Clark and his contemporaries commonly added “t” or other hard consonants to the end of their spellings of Native names with a terminal glottal stop, such as Ne’cos’. |

| ↑17 | See, e.g., https://www.nps.gov/places/necus-park.htm. |

| ↑18 | In Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 80–81. |

| ↑19 | Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 454; Jacobs, “Ethnographic Notes,” Folder 106:6:64. |

| ↑20 | Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 416. |

| ↑21 | Nancy J. Turner and Harriet V. Kuhnlein, “Two Important ‘Root’ Foods of the Northwest Coast Indians: Springbank Clover (Trifolium wormskioldii) and Pacific Silverweed (Potentilla anserina ssp. pacifica),” Economic Botany 36:4 (1982): 411–32. |

| ↑22 | In Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook,” 416. |

| ↑23 | Horace S. Lyman, “Indian Names,” The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 1:3 (1900): 316–26. |

| ↑24 | Charles E. McChesney, ed., Rolls of Certain Indian Tribes in Oregon and Washington (Fairfield, WA: Ye Galleon Press, 1906 [1969]); National Anthropological Archives, Photograph Notes-Tillamook, compiled by Marguerite Stasek (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives, n.d.). |

| ↑25 | National Anthropological Archives, Photograph Notes—Tillamook, compiled by Marguerite Stasek. |

| ↑26 | Clifford M. Scovell, “The History of Harry William Scovell,” Unpublished ms. (Tillamook, OR: Tillamook County Pioneer Museum, n.d.). See also Adams Family files, Unpublished files (Tillamook, OR: Tillamook County Pioneer Museum, n.d.); Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 33–37. This may be a reference to the Catholic mission at French Prairie, founded in the 1830s. |

| ↑27 | Obituary-Illga (Adams)-Tillamook Indian, Bay City Examiner, 10 October 1890. |

| ↑28 | Clara Pearson in Jacobs, Ethnographic Notes, Folder 106. |

| ↑29 | Joe Scovell in Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 55–63; Douglas Deur, “Hobsonville Indian Community,” Oregon Encyclopedia. Digital resource. (Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 2021) https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/squawtown_at_hobsonville/#.YafQMNDMI2w; McChesney, Rolls of Certain Indian Tribes, 63; Floyd Trowbridge, “‘Mother’ Adams, aged 113, is Dead,” Bay City Examiner, 20 December 1912. |

| ↑30 | Notable examples include Elizabeth Derr Jacobs, Nehalem-Tillamook Tales (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1990 [Eugene: University of Oregon Press, 1959]); Jacobs, The Nehalem Tillamook; Jacobs, Ethnographic Notes; Edel, Lexical Notes; Harrington, “Alaska/Northwest Coast: Tillamook.” |

| ↑31 | Vaughan, An Early History, 8. |

| ↑32 | Betty Obrist, in Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 27–28. |

| ↑33 | Douglas Deur, “The Making of Seaside’s ‘Indian Place’: Enduring and Contested Native Spaces on Oregon’s North Coast,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 117 no. 4 (2016): 536–73. |

| ↑34 | Mrs. John [Mary] Gerritse, “Gerritse family-Interview transcription,” Unpublished ms. (Seaside, OR: Seaside Historical Society Museum collections, n.d.). |

| ↑35 | A.W. Norblad, in Jack Fosmark, “Elk Creek Toll Road,” Unpublished ms. (Seaside, OR: Seaside Historical Society Museum collections, n.d.); Samuel Dicken, Pioneer Trails on the Oregon Coast (Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1978), 17–19. |

| ↑36 | John Brallier, “Interview with Mr. John Brallier,” Unpublished ms. (Seaside, OR: Seaside Historical Society Museum collections, 1957). |

| ↑37 | Harriet Munnick, “Interview with J. Brallier,” Unpublished ms. (Astoria, OR: Clatsop County Historical Society collections, n.d.); Deur, Community, Place, and Persistence, 25–26, 39. |