Around the Bend

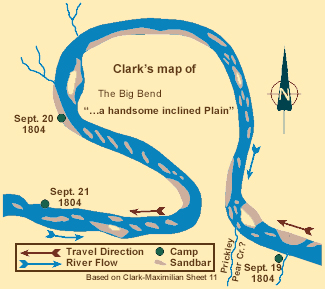

The huge meander called the Big Bend, or Grand Detour had been a well-known Missouri River landmark for many years when the Corps of Discovery arrived at its lower bend on 19 September 1804. Captain Clark dispatched George Drouillard and John Shields across the neck, or “gouge” with the horse to hunt, and dry meat, while the rest of the party proceeded around the bend. Clark himself explored the area.

We Sent a man to step off the Distance across the gouge. He made it 2000 yds. The distance around is 30 miles. The hills extend thro the gouge and is about 200 foot above the water. In the bend as also the two opposite Sides both abov and below the bend is a butifull inclined Plain in which there is great numbers of Buffalow, Elk & Goats in view, feeding & Scipping on those Plains.

According to modern maps the neck is now 8,500 feet wide (1.6 miles; 2.6 km), even though the water level has been raised by Big Bend Dam, 15 miles downstream. Also, the distance around the oxbow is 22 miles (35.42 km).[1]For more detailed census data from the Lower Brule Reservation, visit the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs online. members of the Sicangu, or Lower Brule Sioux tribe, whose ancestors Lewis and Clark encountered downriver from here in August 1804. On the left side of the river is the Crow Creek Reservation, home to 1,230 of the 2,421 enrolled Wič”yena (once erroneously called Nakota) Sioux.

Narrow Escape

At about 1:30 on the morning of 20 September 1805, Clark reported,

the Sand bar on which we Camped began to under min[e] and give way which allarmed the Sergeant on Guard, the motion of the boat awakened me; I get up & by the light of the moon observed that the land had given away both above and below our Camp & was falling in fast. I ordered all hands on as quick as possible & pushed off, we had pushed off but a few minets before the bank under which the Boat & perogus lay give way, which would Certainly have Sunk both Perogues, by the time we made the opsd. Shore our Camp fell in, we made a . . . 2d Camp for the remainder of the night & at Daylight proeeded on to the Gouge of this Great bend and Brackfast.

Geologic Holdout

The Corps’ narrow escape was but another chapter in their riverine education. As humorist George Fitch wrote, back in 1907, the Missouri River is “the original loop-the-loop artist,” obsessed by an impulse to go straight. Indeed, there’s plenty of evidence along the lower reaches of the river that other oxbows were cut off from time to time. Clark himself mentioned seeing one or two. So why is the Big Bend still a big bend?

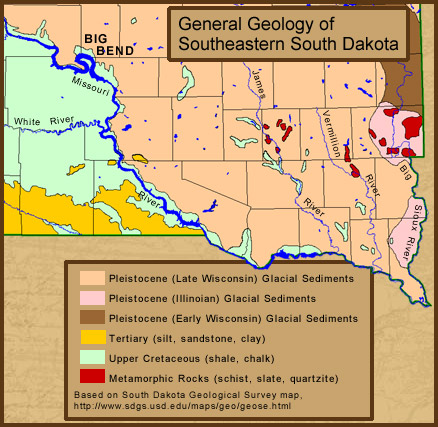

In the first place, the river simply hasn’t had enough time to change its ways here. Second, the geological conditions the river has to cope with have resisted its best efforts to make a shortcut. The following map shows that the Missouri flows through shale bedrock at the edge of the Pleistocene glacial zone.

Third, the neck of the oxbow is high enough—180 to 200 feet—that it has never been topped by springtime floodwater. Moreover, as shown in the Missouri River Commission map on the next page, there is a sheer cliff of indurated shale in the crook of the upstream bend, which impedes erosion. Finally, when Big Bend Dam was completed 15 miles downstream in 1966, the river above it became a deep 80-mile-long lake, and the old annual assaults of spring runoff on the banks of the neck were considerably diminished.[2]The reservoir, called Lake Sharpe, was named for Governor Merrill Q. Sharpe of South Dakota, who was a forceful advocate for the building of four dams on the Missouri within the boundaries of his … Continue reading (Jim Wark took the photograph on the preceding page in May 1999, when the reservoir was at full pool for the season.)

Of course, if the Big Bend were on the commercial shipping channel that begins downriver at Sioux City, Iowa, the Corps of Engineers would have been obliged fifty years ago to cut through the neck for the convenience of barge traffic. Incidentally, a suggestion was once made to tunnel through the neck and install a turbine to generate electricity, but the drop, or “head,” would have been only one foot, and so the benefits would not have offset the cost.

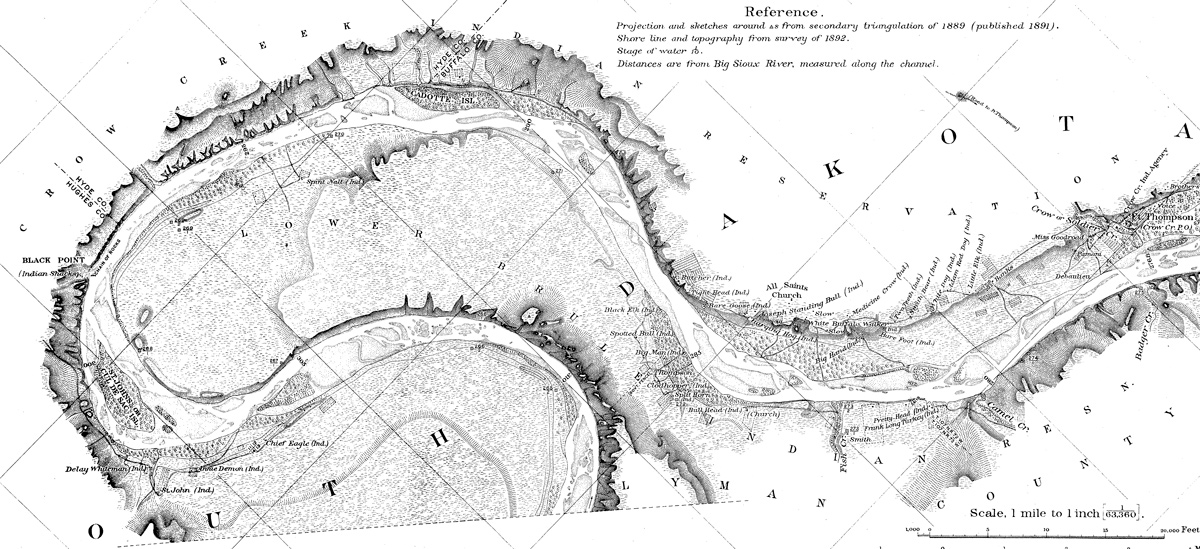

MRC map of the Big Bend

Missouri River Commission, detail, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey, www.cerc.usgs.gov/data/1894maps/P38s.html.

In the 1880s the Big Bend was still “Crouded with sand bars,” as Clark had noted. The printed matter on the right bank of the east meander-bend identifies Sioux dwellings on the Lower Brule Indian Reservation. The words on the left bank of the river at that point identify homesteads on the Crow Creek Reservation.

The Missouri River Commission was established by Congress in about 1884 to direct a methodical development of control measures to assure a clear channel and consistent minimum depth to facilitate river commerce. But by that time several transcontinental railroads had taken over the shipment of goods and people across the West, and in 1902 the MRC was abolished, leaving as virtually its sole legacy a set of eighty-three beautifully crafted maps of the Missouri from the Mississippi to the Three Forks, drawn from surveys made as early as 1879, and published in 1893.

Further Reading

Daniel B. Botkin, Passage of Discovery: The American Rivers Guide to the Missouri River of Lewis and Clark (New York: Penguin Putnam Inc., 1999), 104-111.

John Paul Gries, Roadside Geology of South Dakota (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press, 1996), 81-87.

The Big Bend of the Missouri is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The site is open to the public and managed by South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | For more detailed census data from the Lower Brule Reservation, visit the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs online. |

|---|---|

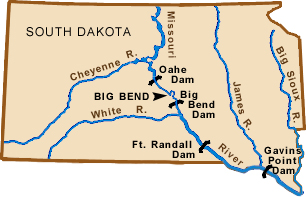

| ↑2 | The reservoir, called Lake Sharpe, was named for Governor Merrill Q. Sharpe of South Dakota, who was a forceful advocate for the building of four dams on the Missouri within the boundaries of his state (see map): Gavins Point Dam at Yankton (1952-57), Fort Randall Dam at Pickstown (1946-54), Big Bend Dam at Fort Thompson (1959-66), and Oahe Dam at Pierre (1948-62). They impound a total of 442 of the 500 miles of the Missouri River in South Dakota. |