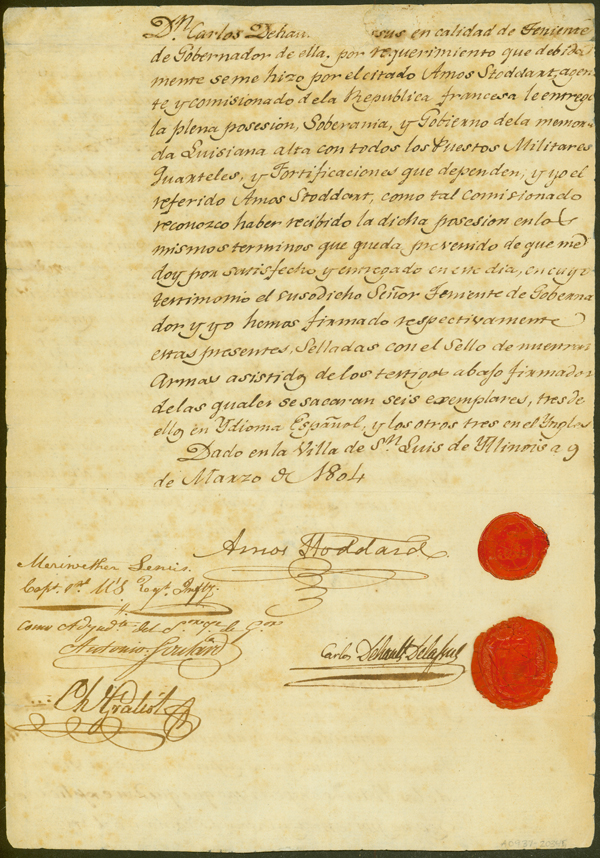

Louisiana Purchase Transfer Document, Page 2

Louisiana Purchase Transfer Collection, 1783-1953, Missouri Historical Society.

This document formerly transferred ownership of Upper Louisiana from Spain to France, and then from France to the United States. Amos Stoddard‘s signature is first, to the left of the red seal. Meriwether Lewis‘s signature is just below and to the left of Stoddard’s.

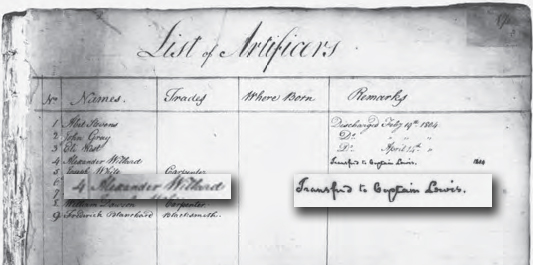

The artificer’s page from Amos Stoddard’s company book shows the entry (see insets) transferring Alexander Willard to the Corps of Discovery.[2]Bob Moore, “Company Books and what they tell us about the Corps of Discovery,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 27 No. 3 (August 2001), 21.

Built for Trade

St. Louis, unlike towns which evolved gradually from a crossroads or farming community, began life as a planned village, its purpose to serve as a mercantile center for the fur trade (a position, I might add, which it held for two centuries). To review briefly: Pierre Laclède Liguest a partner in the New Orleans form of Maxent, Laclède and Company, ascended the Mississippi River in 1763 with his young lieutenant, Auguste Chouteau, to sound out an appropriate location for a fur trading post. Laclède and Chouteau scouted the land on the right bank of the Mississippi until Laclède was satisfied that the sheltered landing point just below the entrance of the Missouri River into the Mississippi, and near the mouth of the Illinois River, was suitable for what, in his own words, “might hereafter become one of the finest cities in America.” In February 1764 the fourteen-year-old Chouteau and a party of workmen laid out the foundation, after Laclède’s specific plans, for that future fine city.

Meanwhile, back at the capital, things had changed drastically. In 1763, France ceded to Great Britain all her lands east of the Mississippi and secretly relinquished control of Louisiana, as the territory west of the Mississippi was called, to Spain. Many French residents of such east side villages as Fort de Chartres, Kaskaskia, St. Philippe, and Cahokia, chose to move west rather than endure British rule, and crossed to Laclède’s new village bearing their household goods and even such parts of their houses as doors and windows. Those already settled on the west bank, though hardly pleased with the change in government, felt that Spanish rule was not significantly different from French, and stayed on. Actually, their lives were but superficially changed; while the administration of the territory was conducted by Spanish officials after 1770, the population maintained its French ways and continued to conduct most of its affairs in the French language. Then in 1800 Spain—secretly again—retroceded Louisiana to France, and in 1803 Napoleon, hard pressed for funds and engaged in war with England, sold the territory to the United States in what has been aptly described as “the biggest real estate deal in history.”

Captain Stoddard Takes Charge

And this brings us to the year of our story, 1804. It was the year of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, but we must remember that this phenomenal pair and their historic mission were not the only show in town. In March of that year the little village shed it ambiguous Spanish-French parentage and took on full American citizenship.

United States Army Captain Amos Stoddard, acting for France and the United States, officially received Louisiana from the Spanish for the French on 9 March 1804, and on the following day lowered the French flag and hoisted the flag of the United States over Government House. The original Document of Transfer is in the archives of the Missouri Historical Society.

Stoddard, appointed by President Jefferson to take over the territory and to act as its civil and military commandant, addressed the populace on 3 March 1804 with the assurance:

You are divested of the character of Subjects and clothed with that of citizens. You now form an integral part of a great community, the powers of whose government are circumscribed and defined by charter, and the liberty of the citizen extended and secured.”

Privately, and less formally, Stoddard gives his impressions of the new territorial capital in a letter to his mother in which he writes:

I have the honor to act as Governor of the Province . . . The number of souls in my jurisdiction is about twelve thousand. The country is beautiful beyond description. The lands contain marrow and fatness. St. Louis contains about 200 houses, mostly very large and built of stone, it is elevated and healthy, and the people are rich and hospitable; they live in a style equal to those in the large seaport towns, and I find no want of education among them.

Lt. Governor Carlos Delassus entertained him with a dinner, and honor, and so, he wrote, “Accordingly I also gave a public dinner and ball, at my own house, and the expense amounted to 622 dollars and 75 cents. I am in hopes, however, that the Government will remunerate me for this expense.”

Also in the Missouri Historical Society’s files is a follow-up to this letter, written in 1813 by William Clark to his nephew, John O’Fallon. “Majr Amos Stoddard I am informed is dead. He owes me $200. cash which I lent him at Saint Louis in the year 1804 to pay for a public dinner given at that place which dinner he was allowed for in his publick accounts by the Government. I wish you to inquire . . . and if possible to procure it for me.”

Officially, Stoddard reported on 26 March 1804 to U.S. Commissioners William Claiborne and James Wilkinson:

It is an endless task to find out the laws and steady maxims of the late Spanish government . . . the laws, rules of justice, and the forms of proceeding, were almost wholly arbitrary, for each successive Lt. Gov. has totally changed or abrogated those established by his predecessors. The criminal code is very defective.

All capital offenders must be sent to New Orleans for trial—but what is, and what is not, capital, depends more on the aggravation, than on the description, of the offense.

He states that the citizens had expressed no dissatisfaction at the governmental change, and the Spanish officials had aided him in every was possible. “The ceremonies of investiture,” he admits, “drew tears from the eyes of all-but these were not tears of regret; they had”—and here, unfortunately, the letter ends. I would be fatuous to think that the American regime had been enthusiastically embraced by all. In fact, there still remain those in St. Louis who express the opinion that any claims this city might have had as a place for gracious and elegant living went out with the arrival of the “Bostonnais,” or Americans.

Lewis Helps Out

In another letter of Stoddard’s, also of 26 March 1804, this one to Claiborne, we see the predicament of a young officer far from headquarters, trying to establish a new government with no funds at hand. He writes:

I have been obliged to rent a convenient house for the security of the public records and papers, and for the transaction of my business. A Secretary. acquainted with three languages, was also indispensable . . . . I experienced infinite trouble from the Indians. They crowd here by the hundreds to see their new father, and to hear his words. The friendship under the former Government was purchased by presents; they expect the continuance of them; and it is apprehended that, if the customary presents be denied or suspended, they will commit depredations or murders on the Inhabitants. As yet I have only furnished them with provisions; and also I am not authorized to present them with anything else, Capt Lewis has furnished them with whiskey and Tobacco. They really expect some articles of clothing, but we have hitherto avoided a compliance with these requests . . . . It is impossible to state the various items of expense . . . . I would therefore thank you to inform me whether I am at liberty to make any drafts on you for such as are indispensable.

We can only sympathize with Stoddard, who was already in hock for $200 to Clark, and had borrowed from Meriwether Lewis some of the grade goods which might have come in very handy in some of those tough days on the road. In reply to his pleas, he received the reassuring instructions to “send a suitable person to Kaskaskia or Vincennes to dispose of bills . . . not exceeding $3,000, distinguishing between what is to be expended for barracks and for the garrison . . . and expenses incurred in the civil department for expresses, Interpreters, and other incidental expenses, which should be drawn for by the Commanding officer, Lt. Mulford, who will have joined you before this reaches you.” Things really haven’t changed much.

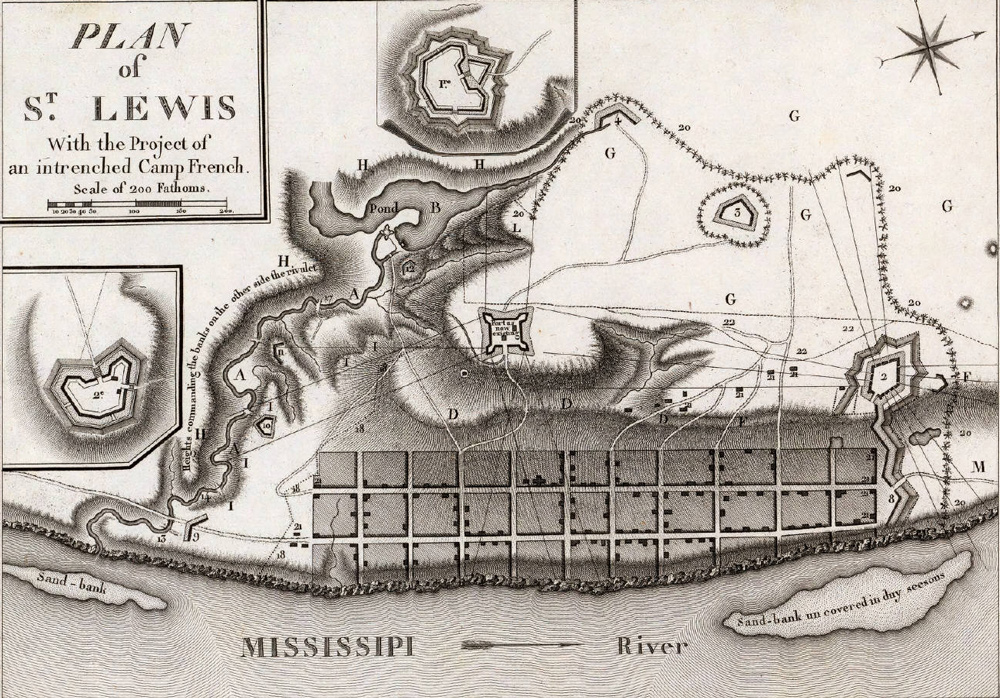

“Plan of St. Lewis with the Project of an Intrenched Camp French”

Georges Henri Victor Collot (1752–1805)

Engraved map from Voyage dans l’Amérique Septentrionale. Page 2. Paris: A. Bertrad, 1826. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

French General Victor Collot inspected St. Louis in 1796, but this map was not published until 1826. Several features are numbered or lettered, but no key is known to exist.

—Kristopher Townsend, ed.

Called the “First Scientist of the Mississippi Valley,”[3]Meany, p. 309, n. 24, citing W.V. Byars, The First Scientist in the Mississippi Valley, (pamphlet), 14-15. Antoine Saugrain was a chemist and naturalist and the only physician in the frontier community of St. Louis when Lewis and Clark arrived there in 1803. Described by a contemporary as “a cheerful, sprightly little Frenchman”—he was just four-feet-six—he had been appointed by President Jefferson, after the cession of Louisiana to the United States, as the resident surgeon at Fort Bellefontaine, a nearby military post.[4]Saugrain de Vigni, Antoine Francois, 1783-1821, L’Odysee Americaine d’une Famille Francaise [par] le docteur Antoine Saugraine; H. Foure Selter, ed. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1936), 33.

The doctor was something of a showman and seems to have liked nothing better than putting on scientific demonstrations. These included placing “little phosphoric matches” in a glass tube, sucking the air out to create a vacuum, then breaking the glass—at which point the matches ignited spontaneously.

—Robert R. Hunt

“Matches and Magic: Just how did the Corps of Discovery make fire?,” We Proceeded On Volume 20, No. 1 (February 1994), 15.

Clark’s Inspection

Meriwether Lewis, whose signature appears on the Document of Transfer, had arrived in the village in the winter of 1803, and was perhaps too busy preparing for the expedition to record his impressions in detail. William Clark, however, had come to St. Louis as early as 1797, when he was trying to straighten out the affairs of his brother, George Rogers Clark. He recorded his impressions in a diary which amply illustrates both his powers of observation and his widely creative spelling. He was “delighted from the ferry with the Situation of this town, which is on the decline of a hill, commanding a butifull view of the river. Crossed & visited the Govr. Zeno Trudo & was received with the mark of hospitality that is to be annext to a French Charector. After seeing Mr. Grattiot, Mr. Shoto, &c, dined at the Govr. In the evening went to a ball given by Mr. Cl. Shoto where I saw all the fine girls and buchish Gentlemen. At almost day returned to Mr. Grasietts & sleap.” The next day he “vie’d the Town, found it to be in a thriveing state, a number of Stone houses built and on the stocks, tho all in French stile, small fort, one Bastion & 5 towers round guards the town, some Inds mouns about 1/2 miles above. The shore is of limestone rock, and good . . . 2 streets parrelell.”

Laclède had chosen his site wisely, following—whether he was aware of it or not—the regulations set out by the Spanish for founding colonial outposts: “an elevated place, where are to be found health, strength, fertility, and abundance of land for farming and pasturage, fuel and wood for building, fresh water, (and) a native people” (someone to do the work). The Mississippi was of course the regional highway, providing access from and to fur trade posts in all directions, and to the capital city of New Orleans.

Water Port

Just as important, the river water provided beverage for man and beast, and this particular water was considered the tastiest and most salubrious to be found anywhere. The only processing the water underwent was “settling”—that is, after it had been laboriously hauled uphill in casks mounted on carts, it was poured into large earthenware jars where the mud settled to the bottom. Cooled by evaporation, and taken as it came, it was described as “somewhat rich in flavor, as well as in color,” and many stoutly contended that no water on earth could compare to that of the Mississippi, “au naturel.” In later years Mark Twain declared, “every tumbler of it holds an acre in solution. You can separate the land from the water as easy as Genesis, and then you will find them both good, the one to eat, the other to drink . . . . But the native do not take them separately, but together, as nature mixed them. It is good for steamboating and good to drink, but it is worthless for all other purposes except baptizing.”

The visiting Viscountess Avonmore mistook it for iced coffee, and both Senator Thomas Hart Benton and Dr. Charles Pope carried a supply of it when they traveled.

And until the beginning of this century the water coming through the taps stayed pretty much the same; it was truly said that St. Louisans could not see their feet in the bathtub. Ironically, it was in 1904 when the world celebrated the centenary of the Louisiana Purchase at the St. Louis World’s Fair, that the city’s chemists and engineers were finally able to produce the clear water we take for granted today.

Fortunately, river water was not needed for the family laundry. This was done, whether by housewives or slaves, at Choteau’s Pond, the body of water produced by the mill operated from the earliest days on La Petite Riviere. The pond offered not only laundry facilities, but also a recreational area for picnics and boating, diversions enjoyed until the growth of the city and industrial pollution forced the draining of the pond in the mid-nineteenth century to provide land for the railroad yards.

Industry

Although Amos Stoddard “found no want of education among them,” the early settlers had no established institutions of learning. Jean Baptiste Trudeau taught sons of the villagers on an irregular schedule, taking time off for occasional hunting and trapping expeditions. Just about everybody did this. In 1778 Lt. Governor Fernando de Leyba complained to the Governor General at New Orleans that although the country was suitable for crops, the settlers neglected their farming, being interested only in trading with the Indians-” All are, or wish to be, merchants.” From this situation came St. Louis’s first nickname, Pain Court-” short of bread.”

One other teacher, Mme Parie Rigauche, kept a school for girls in the late 1790’s; this lasted but a few years. Sons of wealthier families were sent way for their education. Auguste Aristide Chouteau, eldest son of Auguste, was sent in 1802, at the age of nine, to Montreal. Charles Gratiot and Auguste Pierre Chouteau graduated in 1806 from West Point, and young Silvestre Labbadie studied in France in the 1790s. Actually, and hardly to the city’s credit, the first public school in St. Louis was not opened until 1838.

Lack of schools did not mean however, that the village’s leading citizens were ignorant. John Francis McDermott’s study, Private Libraries in Creole St. Louis, shows that of the village’s approximately 1,000 residents in 1800, at least 56 family heads possessed books, and that before 1804 there were some 2,000 to 3,000 volumes in private libraries. Pierre Laclède’s collection emphasized political theory, history, and philosophy, while that of Auguste Chouteau contained mainly histories and works of the free thinkers, many of the listed on the Index. Dr. Antoine Saugrain, a French emigre who came to St. Louis via Gallipolis, Ohio, and was the town’s only physician from 1800 to 1806, possessed a considerable library of scientific works, dramas, and at least one cookbook, The Science of Cooking, published in Paris in 1776 – a collection now housed in the Missouri Historical Society. It was this same Dr. Saugrain who provided sulphur matches, then practically unknown, for the Lewis and Clark expedition. His stone house was at present-day Second and Lombard streets; here his wife maintained a splendid garden that is said to have charmed and inspired Henry Shaw on his rides through the town.

For industry, the village boasted in 1804 such manufactures as shoemaking, coopering, and gunsmithing, all carried on in the homes of the artisans. As early as 1766 Joseph Taillon dammed La Petite Riviere for his mill, which was later acquired by Auguste Chouteau and provided the already-mentioned Chouteau’s Pond. At least two bakeries existed by 1803, one operated by Francois Barrera in a structure joined to his Third Street dwelling, the other by Joseph Robidoux in a two-story building. Four tanners were known to have been in business before 1800, and the town had one potter, Joseph Eberlein an “artiste” who came to the village about 1795 and operated a furnace for baking earthenware.

Emilie Ann Gratiot Chouteau (1792–1862)

Pierre “Cadet” Chouteau Jr. (1789–1865)

Composite image created by Kristopher Townsend. Original images courtesy of the Missouri History Museum Objects Collection.

Emilie Ann Gratiot and her future husband, Pierre Chouteau, Jr. were children when the Expedition arrived in St. Louis. Pierre was the grandson of St. Louis founder Peirre de Laclède. Emilie was the daughter of Charles Gratiot who financed part of George Rogers Clark’s Illinois campaign and translated for Lewis during his meeting with the Spanish Governor in St. Louis. The children would have been teenagers when the Expedition returned in 1806. The two were married in 1813 or 1814.

—Kristopher K. Townsend, ed.

Domestic Life

Twentieth century accounts of the early days tend to generalize and romanticize the early settlers in a way that would make Garrison Keillor’s description of the Lake Wobegonites sound downright modest. In St. Louis, all the men were industrious and enterprising; all the women were virtuous and tidy, and all the children were deferential and well behaved. According to one writer, the housewife’s duties included chaperoning children at the obligatory classes in dancing the minuet; early education of these children; the care of what were generally large families; management of finances when the master of the house was off on his trading ventures; laying in provisions for the household for the months that it took to receive goods from New Orleans; managing the kitchen; sewing clothing for the household; disciplining the Indian and black slaves “strictly but fairly,” and, through all this, remaining gay, sprightly, and a real helpmate to her husband. “From sunrise to sundown she was busy making the house comfortable and cheerful for her husband. After supper she, like her husband, rested and forgot the cares of the day.” And oh yes, she “set an example of sincere religiousness and great patience, a quality which she must have possessed in great abundance to be able to retain her charm of manner.”

If any woman in the room recognizes herself or any acquaintance in this picture, let her raise her hand. Still, things were not easy for the eighteenth-century housewife, and there was, I fear, little sitting around in the evenings chatting amiably and sloughing off the cares of the day.

If nothing else, the housewife must be a good cook, Kitchens were usually separate from the main house, and cooking was done in open fireplaces with cranes on each side of the hearth. A bar of iron at the top of the fireplace provided a place to hang kettles to boil, or to roast game. Long rods with hooks were used to remove pots from the fire, and cooking spoons had long handles. Locally procured provisions included turkeys brought in by Indians for barter; bear which furnished tastier hams than the wild running hogs; wild cattle, fish, and various fruits and vegetables. Spices and condiments, mentioned by Stoddard as “extremely dear,” were imported and brought up from New Orleans.

In addition to the separate kitchens, outbuildings might include a barn, a henhouse, a milk house, a shed, a storehouse, an outdoor bake oven, a latrine, a stable, slave quarters, and outside cellar,a pigeon house, and a pigsty. And just in case you doubt that even the worst news sounds good in French, compare that word pigsty to its local French counterpart, cochonniere. It could be the honeymoon suite at the Ritz.

Open fires heated the houses, as driftwood and logs were easily procured from the commons. Stoves, imported from New Orleans, were in stock by 1798 in the store of Clamorgan and Régis Loisel, but were too expensive for the average home. For interior lighting there were candles, grease lamps, and rush lights like those of rural France.

Town Houses

The town was made up of private houses on quarter-block lots, each surrounded by a high palisade fence. In case of danger to the village, barriers at the ends of the streets formed with these fences a continuous protective wall. There was no retail district, no industrial center, no inn or hotel. The more prominent citizens had large houses; that of Auguste Chouteau was described by John F. Darby as “an elegant domicile fronting on Main St. His dwelling and houses for his servants occupied the whole square . . . . The walls were two and a half feet thick, of solid stone work, two stories high, and surrounded by a large piazza. The floors were of black walnut, and were polished so finely that they reflected like a mirror. Col. Chouteau had a train of servants, and every morning after breakfast some of those inmates of his household were down on their knees for hours.” And Mme Dubreuil, it was said, had one slave who did nothing but wax furniture and woodwork.

Paint was scarce, but the abundant limestone made for plenty of whitewash, and it was this which covered the inside and outside walls of most houses. In 1807, traveler Christian Schulz mentioned seeing in St. Louis “about 200 houses, which, from the whiteness of a considerable number of them, as they are rough-cast and white-washed, appear to great advantage as you approach town.”

Among the most valued household pieces were armoires, constructed of walnut or cherry and often made so that they could be taken apart for moving. Beds had canopies and side curtains, bolsters stuffed with feathers or Spanish moss, covered with ticking or deer skin; heavy linen sheets, buffalo robes, and quilts. Mosquito barriers of light linen or cotton were a must for the summer months. Chairs were corron and inexpensive, and some had cross-bar connecting finials to form a prie-dieu. Dining rooms were large, and furnished with side tables which could be added to the center table to accommodate large families and guests. Cupboards and sideboards lined the dining room walls. An armoire of the Chouteau family can still be seen at the local History Museum, as well as some of the china brought from France. The china, highly decorated earthenware, is still produced as the Strasbourg pattern by the French firm of Lunevialla, and, incidentally, can be purchased even now in the Museum Shop.

The typical house was nearly square, and usually one story high. It had the usual hip roof, steep on the long sides and almost vertical at the ends, and a galerie, shaded by the sloping roof, a necessity in this warm climate. Originally roofs were thatched, but thatch was a fire hazard in the dry atmosphere, and by 1766 shingles had become standard, since straight-grained wood for making them was plentiful.

Clothing

Clothing was simple and practical. One duty the housewife was spared (perhaps you noticed it was not included in the list of her accomplishments) was the production of homespun fabrics. Spinning wheels and looms were absent, because old French law prohibited home weaving to assure the purchase of material manufactured in France. The usual male outfit consisted of deerskin or coarse cotton pants, a long cotton shirt, a head kerchief, and moccasins. In cold weather a woolen cape was worn, along with fur mittens attached schoolboy-style to a cord to prevent their being lost. The women typically wore long cotton or woolen skirts, linen or cotton blouses, short jackets, and kerchiefs. The more affluent of both sexes had elegant clothes for special occasions; these were of fine silks, and were accessorized with fancy gloves and slippers for the ladies and buckled pumps for the men.

Religion

Religion was a simple matter, definable in one word: Catholic, the official state religion of both the French and Spanish regimes. Land was set aside in Laclède’s original plan for a church, and priests made occasional visits to perform marriages, funerals, and baptism, but there was no resident pastor until the arrival of Father Bernard de Limpach in 1776. Sundays were both religious and social; after Mass there were auctions, public discussion, land transactions, dancing, and games.

Even before the purchase, Americans were moving west, many desiring farm lands beyond the Mississippi. For the most part these were Protestants, ineligible under Spanish law for residence in Louisiana. Beginning in the 1790s, the Lieutenant Governors encouraged immigration from the East, and chose unofficially to waive the religious requirements. Zenon Trudeau, for example, catechized the newcomers, and if they seemed at least to adhere to some Christian tenets, he would pronounce them “good Catholics” and admit them. Most of these newcomers settled in the rich lands west of the town in such areas as Manchester and Bonhomme. It would be another decade or so after the transfer that Protestantism achieved any lasting foothold in St. Louis.

Dancing was a social grace and activity enjoyed by all. Balls were the accepted form of entertainment, especially for important guests, and even crusty old Frederick Bates observed, “Our balls are gay, spirited and social. The French ladies dance with inimitable grace.” American to the core, he could not resist adding, “I must deplore the singularity of my taste when I confess, that to me, they would be more interesting with a greater show of modesty and correctness of manners.”

Conclusion

Returning now to Amos Stoddard, still bowed under his governmental duties, I will close with a message he must have been happy to convey to Secretary of War Henry Dearborn on 3 June 1804: “I have the pleasure to inform you that Captain Lewis, with his party, began to ascend the Missouri from the village of St. Charles on the 21st ultimo. I acompanied him to that village and he was also attended by most of the principal gentlemen in this place and vicinity. He began his expedition with a Barge of 18 oars, attended by two large perogues all of which were deeply laden, and well manned. I have from him about 60 miles on his route, and it appears that he proceeds about 15 miles per day—a celerity seldom witnessed on the Missouri; and this is the more extraordinary as the time required to ascertain the courses of the river and to make the other necessary observations must considerably retard his progress.”

Well, you all know the rest . . . that expedition, called the “most perfect of its kind in history” opened the west to settlement and made of St. Louis the gateway memorialized by Eero Saarine’s stunning arch.[5]See also on this site St. Louis by Air. And it all came together in 1804.

In present St. Louis, the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial “commemorates Thomas Jefferson‘s vision of the continental expansion of the United States” and is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | Frances H. Stadler, “St. Louis in 1804,” We Proceeded On, Volume 20, No. 1 (February 1994), the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. From a speech presented at the Foundation’s 25th Annual Meeting near St. Louis, Missouri. The original article is provided at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol20no1.pdf#page=11. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Bob Moore, “Company Books and what they tell us about the Corps of Discovery,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 27 No. 3 (August 2001), 21. |

| ↑3 | Meany, p. 309, n. 24, citing W.V. Byars, The First Scientist in the Mississippi Valley, (pamphlet), 14-15. |

| ↑4 | Saugrain de Vigni, Antoine Francois, 1783-1821, L’Odysee Americaine d’une Famille Francaise [par] le docteur Antoine Saugraine; H. Foure Selter, ed. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1936), 33. |

| ↑5 | See also on this site St. Louis by Air. |