Tired and physically sick, the travelers recover and those who can, build five dugout canoes at camp on the Clearwater River. With no time for portages and despite the help of two Nez Perce river guides, several canoe accidents happen while negotiating rapids on the Clearwater and lower Snake. At the Columbia River, they are greeted by a large group of Yakamas and Wanapums.

We call ourselves Ni-mee-poo, which means “The People.” We also call ourselves Tsoopnitpeloo, and Tsoopnitpeloo means “The Walking-Out People”—people from the mountains come to the plains, to hunt buffalo.

After trading for horses with Sacagawea’s people, the expedition turned north and then west, on what would indisputably be the most exhausting and debilitating segment of the entire journey, the passage across the Bitterroot Mountains.

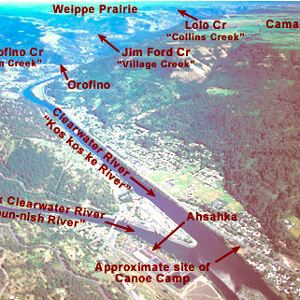

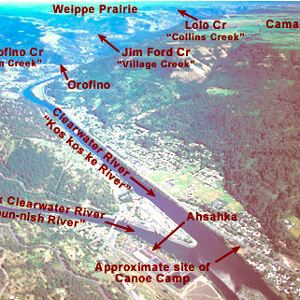

For countless generations, Weippe Prairie (prounouced WEE-yipe), like Travelers’ Rest, was a major node in the transportation, trade, and social networks of the Rocky Mountain West.

Clark spent the night of 21 September 1805 at Twisted Hair’s camp on an island in the Middle Fork of the Clearwater River. The next morning the chief and his son accompanied him back up to the village on Weippe Prairie where he expected to rendezvous with Lewis.

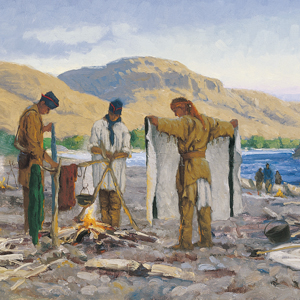

The Clearwater Canoe Camp

by Joseph A. Mussulman

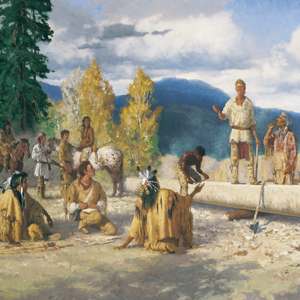

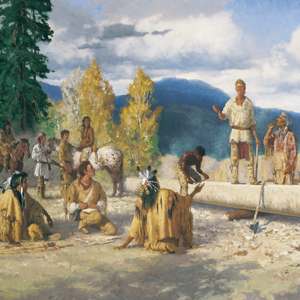

Still sick and exhausted from their recent crossing of the Bitterroot Mountains, Lewis, Clark, and their crew arrived on 26 September 1805, at what they called Canoe Camp, on the Clearwater River.

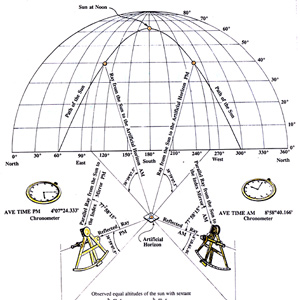

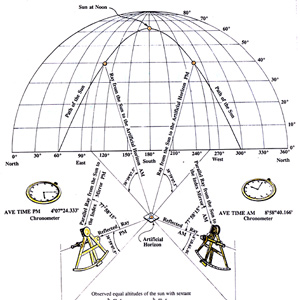

Determining the latitude of a location from a meridian observation of the sun is among the simplest celestial observations to take and to calculate. On 5 October 1805, Clark writes: “Latitude of this place from the mean of two observations is 46°34’56.3″ North.”

October 1, 1805

Burning out the canoes

Clearwater Canoe Camp, ID The men employ the Indian method of hollowing out logs with fire. Clark prepares goods to trade for food, and Lewis preserves a plant specimen.

October 5, 1805

Two Nez Perce guides

Clearwater Canoe Camp, ID Two canoes are put in the water, and the horses are rounded up, branded, and given to Nez Perce caretakers. The expedition adds two Nez Perce guides, Tetoharsky and Twisted Hair.

October 7, 1805

Down the Clearwater

Lenore, ID After a busy day, thirty-three expedition members, Lewis’s dog, Seaman, and two Lemhi Shoshone guides start down the Clearwater. In the five new dugout canoes, challenging rapids test the paddlers’ skills.

At 3 p.m. on 7 October 1805, the Corps loaded their five new dugout canoes–four large ones plus a small one “to look ahead”–and set out down the Clearwater River toward the Columbia and the Pacific beyond.

October 8, 1805

A canoe accident

Potlatch River, ID (Colters Creek) The Clearwater River has many rapids, stretches of calm, and islands inhabited by Nez Perce fishers. Travel stops after a canoe accident. In St. Louis, General Wilkinson tells of sick Indian delegates and the value of interpreter Pierre Dorion.

The Corps’ four-day trip to this point from Canoe Camp on the Clearwater in their five crowded dugouts was a taste of things to come.

October 10, 1805

Clearwater and Snake confluence

Clearwater and Snake rivers, ID-WA The paddlers navigate several rapids and pass many Nez Perce fishing camps. One canoe is damaged when it hits a rock.

Columbia River Basalts

by John W. Jengo

The region of the lower Snake River and the Columbia River’s course through the Columbia Plateau and Gorge experienced volcanic activity starting some 55 million years ago, although the expedition would primarily encounter rock units of Miocene-age.

October 13, 1805

Fast water

Near Ayer, WA To start the day, the non-swimmers portage rifles and scientific equipment while the boatmen navigate a long Snake River rapid. In the evening, they run a two-mile rapid which “ran like a mill race.” In Santa Fe, a Spanish governor gives instructions to stop the expedition from returning.

Now they entered a four-mile-long torrent, its climax a “narrows or narrow rapid” through which a channel 25 yards wide was confined between “rugid rocks” for a solid mile and a half.

Dubbed “Ship Rock” on Clark’s route map, but now known as Monumental Rock, this distinct outcropping of the Lower Monumental Member of the Saddle Mountains Basalt is located on the south bank of the Snake River in Walla Walla County, Washington, just upriver of Lower Monumental Dam.

The boating didn’t improve on 14 October 1805. At the head of a particularly bad three-mile-long rapid, three canoes “Stuk fast for some time . . . and one Struk a rock in the worst part.”

From the moment they dipped their paddles into the Snake River, the Lewis and Clark expedition would not only be following the path of multiple flood basalt flows, but also the route of the colossal Lake Missoula floods that so markedly scoured the basaltic landscape.

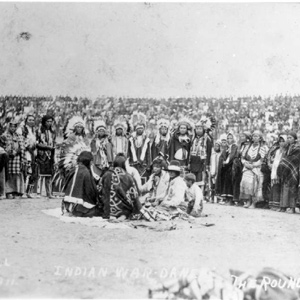

October 16, 1805

A musical welcome

Snake and Columbia rivers, WA The paddlers negotiate the last of the Snake River rapids and arrive at the Columbia River where they are given a musical welcome from a large group of Yakamas and Wanapums. They give the Indians tobacco, peace medals, and other gifts.

In the afternoon of 16 October 1805, the expedition portaged around “the last bad rapid as the Indians Sign to us”–the last on the Snake River, that is–and soon arrived at the “Great River of the West,” the Columbia.

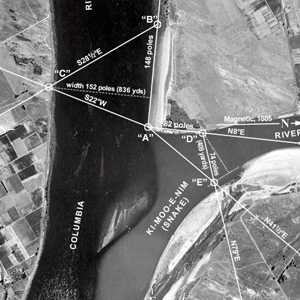

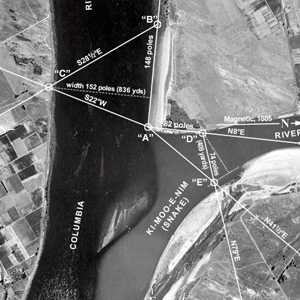

On 17 October 1805, at the junction of the Snake and Columbia rivers, Lewis set out the artificial horizon and got the sextant out of its case. One of the men stood by with the chronometer, ready to read and record the time of Lewis’s measurements.