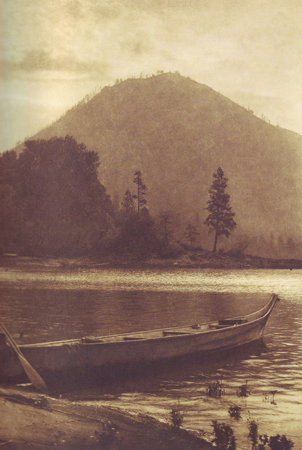

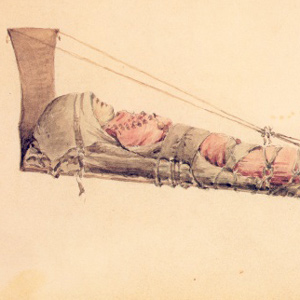

Wind Mountain (1910)

Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s “The North American Indian,” 2003.

In 1910, dispersal and disease so reduced populations that photographer Edward Curtis in 1910 found only a handful of Chilluckittequaws. When photographing them in 1910, Curtis did not make any portraits. Instead, he chose an empty Columbia River-style canoe with Wind Mountain as a backdrop, perhaps an intentional statement.

The Chilluckittequaws were Upper Chinookan people residing on both sides of the Columbia River Gorge. The southern division, called by Clark Smack Shops, lived around the mouth of Hood River and are more properly called the Hood River Chilluckittequaws or Dog River band. The other division lived across the Columbia and around the mouth of the White Salmon River and are more correctly called Woocksockwilliacums or White Salmon.[1]Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 27.

Wind Mountain was at the western extent of a series of Upper Chinookan villages called by Lewis and Clark the “Chilluckkittequaw nation.” Apparently, when asked for a tribal name, the captains were given the word for ‘he pointed at me’. Chilluckittequaw was adopted a century later by early ethnographer Frederick Hodge. Between Wind Mountain and Hood River, nine villages have been identified, some overlapping with Klickitats.[2]David H. French and Katherine S. French, Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau Vol. 12, ed. Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 362–63, 375; Frederick … Continue reading

Ethnologist James Mooney estimated that prior to the 1782–83 smallpox epidemic the population of both the northern and southern Chilluckkittequaws was 3,000.[3]James Mooney, “The Aboriginal Population of America North of Mexico,” ed. John R. Swanton, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections Washington, 1928, page 15, Google Books. In their Estimate of Western Indians, the captains gave 1,400 for the White Salmons and 800 for the Hood Rivers, a total of 2,200.[4]Moulton, Journals, 6:483.Diseases included smallpox and malaria, and often-overlooked alcoholism. Crossing the Columbia River to obtain alcohol—the Chinooks to Astoria and Hood Rivers to White Salmon—was the cause of many drownings.[5]Tony A. Johnson, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 7. For more on smallpox and malaria among the Chinookan Peoples, … Continue reading Edward Curtis described the affliction:

Whiskey was no less potent than the epidemics. One of many instances of this may be cited. In the youth of Tamlaitk, who was born about 1825, the houses of the Indians, placed closely together, extended from Hood river to Indian creek, and many families, not finding room on the level now occupied by the town of Hood River, built their homes on the bench above. On the northern side of the Columbia the whole flat at the mouth of White Salmon river was filled with houses. Whiskey began to be sold on the northern side, and canoes full of drunken Indians returning home would capsize, the helpless natives sinking like stones. Whole families were thus wiped out in a moment. This, combined with an epidemic of cholera, about 1830, almost exterminated two populous villages, and now there are but two survivors.[6]Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian (1907-1930): The Nez Perces. Wallawalla. Umatilla. Cayuse. The Chinookan Tribes Vol 8. (Cambridge, Mass.: The University Press, 1911), 8:86.

In 1855, a few Chilluckittequaw negotiated a treaty with Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Joel Palmer. Chief Wallachin refused to sign saying “I have said that I would not sell my country and I have but one talk.” Eventually, the White Salmons mostly integrated with the Wishrams who moved to the Yakama—then spelled Yakima—Reservation, and the Hood Rivers integrated mostly with the Wascos who mostly moved to Warm Springs Reservation.[7]Ruby, Brown, and Collins, 27–28.

Selected Encounters

April 18, 1806

Tenino horse deal

At a Wishram village, Clark doctors a Tenino chief and his wife and then makes a successful horse deal. At Fort Rock, Lewis has the two large dugouts cut up for fuel, and moves across the river.

October 29, 1805

Friendly villages

Little White Salmon River, WA The expedition encounters friendly villages where they buy food. The climatic transition from the Cascade Mountain’s dry side to its wet side begins.

April 14, 1806

Romantic scenes

In a calm stretch below present Lyle, Washington, Lewis enjoys romantic scenes and a drier climatic zone; and he prepares four plant specimens. The captains are encouraged to see residents with horses.

January 13, 1806

Running out of candles

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Elk tallow is rendered to make new candles, Lewis finds that the area’s elk do not have enough fat to make a sufficient supply, and President Jefferson writes to Lewis’s mother with news of the expedition’s progress.

March 9, 1806

Swans

Fort Clatsop, OR Lewis describes various swans encountered on the journey. John Shields is tasked with making water-resistant bags, and Clatsop traders have beeswax for sale.

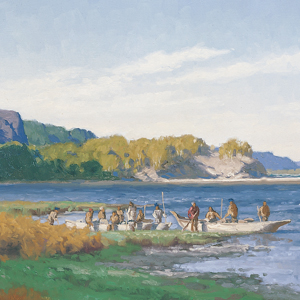

October 28, 1805

Superior Chinookan canoes

Crates Point, The Dalles, OR The expedition sets out from Fort Rock but are soon stopped by headwinds. The captains visit nearby Indians where Lewis takes an Indian vocabulary. Clark sees goods acquired from British traders and superior Chinookan canoes.

October 27, 1805

Taking Indian vocabularies

Fort Rock, The Dalles, OR Visiting Indians give the captains an opportunity to compare the languages and customs of the Sahaptian and Chinookan Peoples living above and below The Dalles of the Columbia.

April 15, 1806

Return to Fort Rock

While paddling up the Columbia, the 33 members see many horses but are unsuccessful in trading for any. They encamp at Fort Rock at present The Dalles, Oregon. Lewis prepares four plant specimens.

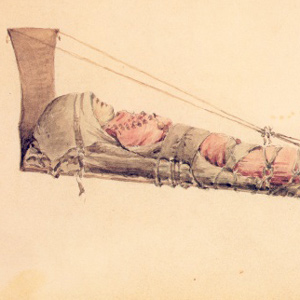

February 15, 1806

Indian horses

Fort Clatsop, OR Ailing Gibson is carried back to Fort Clatsop, and medical treatment begins. The captains describe Indian horses and their availability for trade. They also list the other four-footed mammals they have encountered.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 27. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | David H. French and Katherine S. French, Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau Vol. 12, ed. Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 362–63, 375; Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 1 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1912), 268. |

| ↑3 | James Mooney, “The Aboriginal Population of America North of Mexico,” ed. John R. Swanton, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections Washington, 1928, page 15, Google Books. |

| ↑4 | Moulton, Journals, 6:483. |

| ↑5 | Tony A. Johnson, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 7. For more on smallpox and malaria among the Chinookan Peoples, see The Clatsops. |

| ↑6 | Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian (1907-1930): The Nez Perces. Wallawalla. Umatilla. Cayuse. The Chinookan Tribes Vol 8. (Cambridge, Mass.: The University Press, 1911), 8:86. |

| ↑7 | Ruby, Brown, and Collins, 27–28. |