Ioway

George Catlin (1796–1872)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.[1]“Ioway. 174. Notch-e-ning-a (the No Heart) also called the ‘White Cloud’, Chief of the tribe, . . . 175. Mu-nu-shee-kaw (the White Cloud) Son of the Chief Notch-e-ning-a, and at … Continue reading

Some scholars believe the Sioux name for the Iowa—Santee and Yankton Ayúxba and Lakota ayúxwa—literally translate to ‘sleepy ones’. Anthropological linguist Douglas Parks claims this is among several folk etymologies “that have no linguistic basis.” He also finds that several Algonquian names for the Iowa including names from the Foxes, Kickapoos, and Shawnees, have no known literal meanings other than being the name of the Iowa People—from which the state derives its name. By the late 17th century, writers employed numerous variant spellings. The Lewis and Clark expedition journalists used Aieway, Aiaouez, Ayauwais, and Ayauwa.[2]Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 445.

Iowa culture blended lifeways and customs of their neighbors: Horticulture and a well-defined, patrilineal class system was learned from the Sioux, a clan system was adapted from Algonquian-speaking neighbors, and like the Plains culture, they practiced the summer village method of hunting the American bison.[3]Mildred Mott Wedel, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, 432.

The Iowas were among the first Native Americans to establish trade relations with Europeans. Their trade agreement with French explorer and trader Nicolas Perrot in 1686 set off hostile relations between the Iowas and the Sauks and Foxes, Potawatomis, and Kickapoos. A century later, the Iowa’s location on the Des Moines River enabled them to trade with both the Spanish from St. Louis and the English to the north. In December 1785, Spanish governor of Louisiana reported that the Iowa were middlemen between England and the Otoes.[4]Miró to Rengel, New Orleans, December 12, 1785 in Before Lewis and Clark: Documents Illustrating the History of the Missouri 1785–1804, ed. A. P. Nasatir, Bison Books edition. (Lincoln: … Continue reading

Before the Lewis and Clark Expedition headed up the Missouri River, Clark and Lewis sent a written speech to the Iowa informing them of the transfer of Louisiana and asking them to send a delegation to Washington City. In the past, the Iowas proved their willingness to send emissaries. In 1757, ten Iowas traveled to Montreal with the two members accused of murdering two French men, and they won their pardon. The captains’ invitation was also accepted, and Iowa delegates would join with Arikaras, Poncas, Omahas, and Otoes as part of Too Né’s Washington City delegation. Clark could not have known about the Iowa’s positive response, and he did not hold out much hope of establishing American trade with them. In the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” he wrote:

They are a turbulent savage race, frequently abuse their traders, and commit depredations on those ascending and descending the Missouri. Their trade cannot be expected to increase much.[5]Moulton, Journals, 3:406.

In 1812, Clark would personally escort another Iowa delegation to Washington. In transit, they found out that war with England had been declared. The War of 1812 split the Iowas into two factions: those allied with the Americans and those with England. Further degrading their way of life, lands claimed by the Iowa along the lower Missouri were given to War of 1812 veterans resulting in hostility and animosity between settlers and the Iowas.[6]Wedel, 435.

As Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Clark would join with Michigan governor Lewis Cass to negotiate the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien. The Iowas were a party at the invitation of Clark. The treaty sought peace between the area nations, affirm current tribal boundaries, and put off land cessions to a later date.[7]For a fuller description, see Jay H. Buckley, William Clark: Indian Diplomat (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 97,172–175. Land cessions did eventually come along with the Great Nemaha Reservation in 1837 and the Iowa Reservation in 1854.

Starting in 1878, the Iowa people would be organized into two reservations. Today, the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma is one of two federally recognized Iowan tribes. The other, the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, is headquartered in White Cloud, Kansas in the Iowa Reservation.[8]“Ioway Reservation,” “Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska,” “Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma,” and “Iowa People,” Wikipedia, … Continue reading

Selected Pages and Encounters

October 29, 1804

Mandan-Hidatsa-Arikara peace

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND The standard diplomatic speech is given at a council with the Mandans and Hidatsas. The captains ask them to also smoke the pipe of peace with Arikara Chief Too Né. Medals, flags, and clothing are given as gifts.

June 28, 1804

The Kansa people

The expedition remains another day at the mouth of the Kansas where Lewis determines its latitude. Lewis describes the river and Clark describes the Kansa People.

April 5, 1804

A speech for the Iowas

At Camp River Dubois, Clark and Lewis write speeches for the Iowa and Yanktonai People. They send the speeches—along with Jefferson’s questions, vocabulary, and invitation to visit Washington City.

Too Né’s Delegation

by Joseph A. Mussulman

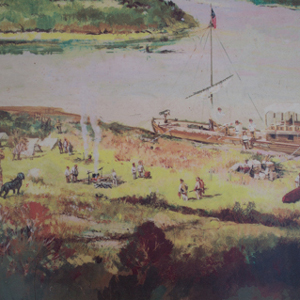

A delegation of chiefs from the Arikara, Ponca, Omaha, Otoe, Iowa, and Missouria nations sailed down the Missouri with Corporal Warfington on the expedition’s keelboat in the spring of 1805. Early in January, 1806, President Jefferson greeted them in Washington City with a formal speech.

June 10, 1804

Abundant prairies

The boats pass the Chariton River, and they find rock suitable for making whetstones. The prairies are full of wild plums, mulberries, hazelnuts, and grapes. They move camp to get away from the mosquitoes.

April 4, 1804

Packing provisions

At camp across from the mouth of the Missouri, Clark has corn, salted pork, flour, and other provisions packed. He also writes a speech for the Iowa Nation to be delivered by trader Lewis Crawford.

May 16, 1804

St. Charles arrival

The boats set out early, pass the coal beds of Charbonier Bluff, and reach St. Charles, an early French settlement on the Missouri River. Many citizens come out to see the event and socialization commences.

June 17, 1804

Rope Walk Camp

Near a traditional river crossing and present-day Waverly, Missouri, the expedition stops to make new rope and oars. The French engagés ask for more food, and several men suffer from boils and dysentery.

January 4, 1806

Jefferson's Indian speech

Fort Clatsop, OR Gass and Shannon travel t to the salt makers’ camp, and Lewis describes Clatsop Indian views on material goods. In Washington City, President Jefferson meets with an Indian delegation organized in part by Lewis and Clark.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Ioway. 174. Notch-e-ning-a (the No Heart) also called the ‘White Cloud’, Chief of the tribe, . . . 175. Mu-nu-shee-kaw (the White Cloud) Son of the Chief Notch-e-ning-a, and at this time Chief of the tribe; 176. Pa-ta-coo-chee (the Shooting Cedar), a brave of distinction, with his war club on his arm.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 12 October 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-da73-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 445. |

| ↑3 | Mildred Mott Wedel, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, 432. |

| ↑4 | Miró to Rengel, New Orleans, December 12, 1785 in Before Lewis and Clark: Documents Illustrating the History of the Missouri 1785–1804, ed. A. P. Nasatir, Bison Books edition. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 125. 125. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, Journals, 3:406. |

| ↑6 | Wedel, 435. |

| ↑7 | For a fuller description, see Jay H. Buckley, William Clark: Indian Diplomat (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 97,172–175. |

| ↑8 | “Ioway Reservation,” “Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska,” “Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma,” and “Iowa People,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ioway_Reservation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iowa_Tribe_of_Kansas_and_Nebraska, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iowa_Tribe_of_Oklahoma, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iowa_people, accessed 11 January 2021. |