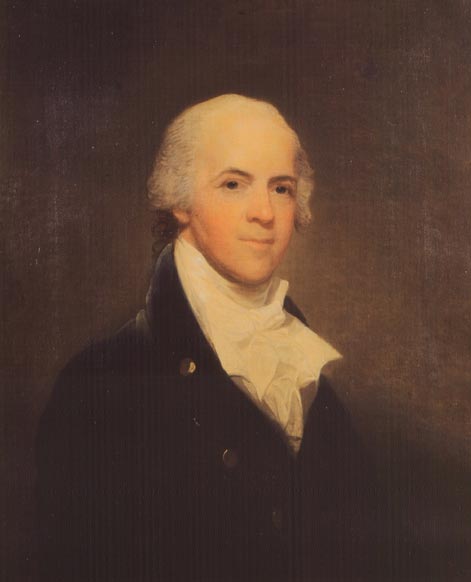

George Logan, the master of Stenton was a persistent pursuer of peace and lifelong observant Quaker, though expelled from meeting in 1791 because of his captaincy in a militia cavalry unit. He opposed the condemnation of the resisters of the whiskey tax and had resigned from from the militia when called upon by Washington to put down the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion.[1]Thomas McKean, one of Lewis’s earliest hosts in Philadelphia, had also been unenthusiastic about Washington’s plan. He was Chief Justice of Pennsylvania at the time of the rebellion. He was the grandson of James Logan, who had been William Penn’s secretary and one of the most politically powerful and scholarly people in the proprietary colony. Stenton was built by James Logan, and it was there that he gathered his famous library that included his own publications in science.

In 1802 George Logan had finished his first year as a United States Senator and had figured in the history of the Expedition by his membership on the three-man committee that approved Jefferson’s request for funds. He was then famous—or infamous—for an unofficial peace-mission to France that attached his name to a Congressional Act prohibiting such action (now codified as 18 U.S.C. 1953).[2]The “Logan Act” made unlawful the personal diplomacy Logan had presumed to attempt. The Act reads in part: “Any citizen of the United States . . . who, without authority of the … Continue reading The Federalist furor over his journey had stilled; he had been honored implicitly by being named chairman of the committee examining final ratification of a convention ending hostility with France. Still to come was his disappointment with Jefferson’s foreign policy. It culminated in a second mission—this time to England—in search of peace during the Madison administration. The attempt was made in the face of contrary general opinion and in technical violation of the Logan Act, but it was shielded by President Madison’s implicit consent.

Stenton House

It may be difficult for 21st-century eyes to fully appreciate the restrained elegance of early Georgian architecture such as this, which aims to reflect the status of a country squire, tempered by the straightforward strength and simplicity befitting a Quaker farmer. Devoid of extravagance and excitement, the house draws its visitors close, to take in its muted details. The patterned brickwork on the symmetrical facade is in Flemish bond style, with glazed headers (the small end of each brick) and plain-faced stretchers (the long side) alternating in each course; the other, asymmetrical walls are laid in English bond—alternating header and stretcher courses. Discreet, shallow hints of Classic pilasters accentuate the corners and frame the transom-crowned portal. Within, the front door opens on a capacious brick-floored entry.

The main and second floors, separated by a brick belt course, each enclose four rooms. In this rural setting the large, double-hung, 12-over-12 windows do not need the burglar-resistant exterior shutters that were obligatory on houses in town, but had folding shutters inside to control light.

Dormers burst through the planes of the hipped roof, which is trimmed by the visual rhythms of isometric dentils beneath the cornices, and crowned by a deck that once was enclosed by a balustrade and embellished with a cupola and a copper weather vane.[3]Roger W. Moss, Historic Houses of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania press, 1998), 144-45.

An Unused Welcome

In the spring of 1806 Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set in motion their bold diplomatic plan, which was to persuade the most influential chiefs of the Lakota Sioux nation to accompany them back to the United States, where they could see for themselves all the promises of civilization, especially in resplendent Philadelphia, the crown jewel of American cities. It is easy to suppose that for several weeks Lewis glowed with the anticipated pleasure of personally escorting those noble Indian potentates into the quiet, restrained grace of George Logan’s lodge. Unfortunately, by early August the plan had fallen apart and there wasn’t time to consummate an alternative. Stenton would never welcome the likes of Chief Black Buffalo nor Chief Buffalo Medicine. Next best would have been an Arikara, but that didn’t pan out either. However, Mandan chief Sheheke , or White Coyote, and his family did return with the expedition, and they did visit Philadelphia sometime between January 15 and February 10, 1807. While there, Chief Sheheke and his wife Yellow Corn sat for their portraits by Charles St. Mémin.[4]Tracy Potter, Sheheke, Mandan Indian Diplomat: The Story of White Coyote, Thomas Jefferson, and Lewis and Clark (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003), 136.

Notes

| ↑1 | Thomas McKean, one of Lewis’s earliest hosts in Philadelphia, had also been unenthusiastic about Washington’s plan. He was Chief Justice of Pennsylvania at the time of the rebellion. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The “Logan Act” made unlawful the personal diplomacy Logan had presumed to attempt. The Act reads in part: “Any citizen of the United States . . . who, without authority of the United States, directly or indirectly commences or carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with intent to influence the measure or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both.” |

| ↑3 | Roger W. Moss, Historic Houses of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania press, 1998), 144-45. |

| ↑4 | Tracy Potter, Sheheke, Mandan Indian Diplomat: The Story of White Coyote, Thomas Jefferson, and Lewis and Clark (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003), 136. |