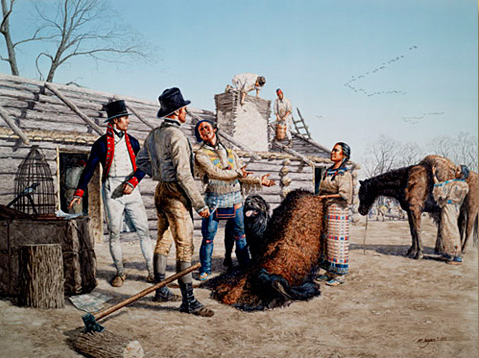

The Charbonneaus’ Gifts

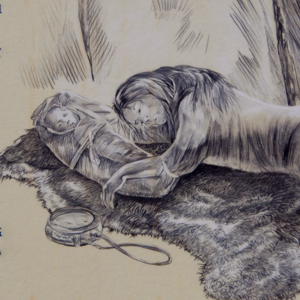

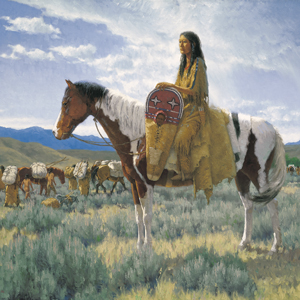

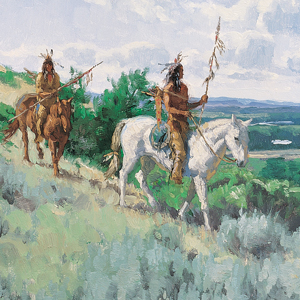

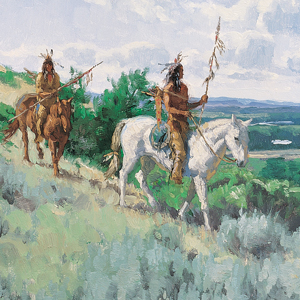

© 2000 Michael Haynes. All Rights Reserved. Prints available at www.mhaynesart.com.

Charbonneau was the oldest member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s permanent party, and he would outlive most of his fellows as he followed the rigorous life of a fur traders, guide, and interpreter. In fact, the fur trade had put him in place to meet the captains and join their expedition.

A French Canadian originally from Quebec, Charbonneau had been living and trading in Metaharta, central of the three Knife River Hidatsa villages, for the North West Company for several years. A week after the expedition arrived, Charbonneau went to meet the captains and learn what was going on. He offered his services as a Hidatsa translator, and mentioned that his two wives were Shoshones.

Almost upon their arrival, the captains learned that a Hidatsa war party was away to Shoshone country, which straddled the Rocky Mountains. They soon would conclude that a Shoshone interpreter was essential to their obtaining horses for the mountain crossing. Charbonneau’s English was shaky, but Drouillard, Pierre Cruzatte, Labiche or Lepage could convey the captains’ questions to him in French. Charbonneau then could speak Hidatsa to his Shoshone wife.

On 4 November 1804, when the captains met Charbonneau, Clark wrote, “we engau [engaged] him to go on with us and take one of his wives to interpret the Snake [Shoshone] language.” The following March, Charbonneau suddenly canceled the arrangement, having “been Corupted” by representatives of the North West and Hudson’s Bay companies visiting in the area. The captains believed that agents of these British firms would fight any assistance to Americans, into whose territory the Brits were extending trade tentacles. After six days, Charbonneau relented and returned to his job.

“of no peculiar merit”

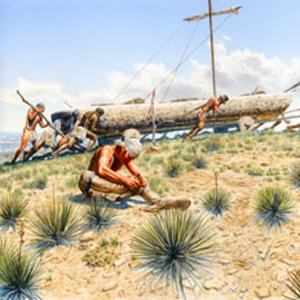

Furthermore, Charbonneau soon proved to be, in Lewis’s kindest terms, “the most timid waterman in the world.” In fact, he was utterly incompetent. He was steering the white pirogue under sail on 13 April 1805—just a week after leaving Fort Mandan—when the wind picked up and he “threw the perogue with her side to the wind,” nearly upsetting the boat.

Worse yet was the incident a month later in eastern Montana, when Charbonneau again was steering the white pirogue under sail. The wind suddenly turned and drove the boat over on its side. As the captains watched helplessly from the opposite shore, the boat righted itself while significant cargo floated loose and the boat filled with water. Charbonneau abandoned the rudder, “still crying to his god for mercy” and ignoring bowman Cruzatte’s orders. Only Cruzatte’s threat “to shoot him instantly” got Charbonneau back to the rudder (see Charbonneau’s Prayer). His tendency to freeze in a crisis showed up again during the flash flood at the Great Falls of the Missouri on 29 June 1805, in which Sacagawea almost drowned and her baby’s spare clothing was lost—as well as Clark’s Umbrella.

Two brief statements in Clark’s 1805 journal hint at Charbonneau’s having a quick temper, but give no details. On 14 August 1805, Clark said he “checked our interpreter for Strikeing his woman at their Dinner.” (Yet, he had been concerned when she was very ill on 15 June 1805, to the point of begging to be released from his contract so he could take her home.) On 25 August 1805, at the height of crucial negotiations for Shoshone horses, he got crosswise with Lewis, who “could not forbear speaking to him with some degree of asperity.” On 10 October 1805, Clark recorded that “a miss understanding took place between Shabono one of our interpreters, and Jo. & R Fields which appears to have originated in just [jest].” An unexplained statement by Clark on 27 October 1805 noted “Some words with Shabono our interpreter about his duty.”

Although Lewis wrote lightheartedly and approvingly of Charbonneau’s recipe for boudin blanc on 9 May 1805, by expedition’s end his summary of the interpreter was partly negative. On the payroll he sent to Henry Dearborn on 15 January 1807, Lewis wrote by Charbonneau’s name: “A man of no peculiar merit; was useful as an interpreter only, in which capacity he discharged his duties with good faith.[1]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854; 2nd ed.; 2 vols. (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:369.

On the other hand, Clark grew to regard Charbonneau with considerable respect. “You have been a long time with me and have conducted your Self in Such a manner as to gain my friendship,” he wrote in a letter to “Charbono” on 20 August 1806, shortly after leaving him at his home. Evidently they had some congenial man-to-man talks sometime along the way, in which the French Canadian revealed some of his hopes and dreams for the future. “If you wish to live with the white people,” Clark’s letter continued,

I will give you a piece of land and furnish you with horses cows & hogs. If you wish to visit your friends in Montrall [i.e., Montreal] I will let you have a horse, and your family shall be taken care of untill your return. If you wish to return as an Interpreter for the Menetarras when the troops come up to form the establishment, you will be with me ready and I will precure you the place—or if you wish to return to trade with the indians and will leave your little Son Pomp with me, I will assist you with merchendize for that purpose from time [to time] and become my self conserned with you in trade on a Small scale that is to say not exceeding a perogue load at one time.[2]Jackson, Letters, 1:315. See also on this site Jean Baptiste Charbonneau.

It was Clark who, on 17 August 1806, “Settled with Touisant Chabono for his Services as an enterpreter the pric of a horse and Lodge purchased of him for public Service in all amounting to 500$ 331/3 cents.” Clark’s spelling of Charbonneau’s surname was simply phonetic for a person with little or no acquaintance with French orthography. The sum ending with “1/3 cents” reflected the comparatively high value of the dollar in that period. The “Lodge” was the leather tepee that was the nightly shelter for the captains, the Charbonneaus, and the civilian interpreter George Drouillard, although it barely lasted until Fort Clatsop was habitable. Clark lamented (17 December 1805) that “our Leather Lodge has become So rotten that the Smallest thing tares it into holes and it is now Scrcely Sufficent to keep . . . the rain off a Spot Sufficiently large for our bead.” Nevertheless it had served them well.

Town Life

Charbonneau and his family eventually went to St. Louis, but stayed only a year and a half. They arrived in September 1809, when their son was four years old, traveling with the army contingent of Chief Sheheke‘s successful return escort. (They would have had a reunion with George Drouillard, who was in the Choteau-employee portion of the escort.) In December, they had little Jean Baptiste baptized, and in the fall of 1810 Toussaint bought land from Clark. But living in that style lasted only over the winter. In the spring of 1811, Toussaint and Sacagawea went back up the Missouri River again, leaving the boy to be raised by Clark.

To gain passage upriver, Charbonneau hired out to fur trader Manuel Lisa, who was making his third trip to the Upper Missouri. Henry M. Brackenridge, traveling in the same group, wrote that the Frenchman, “who had spent many years amongst the Indians, was become weary of civilized life.”[3]Henry M. Brackenridge, Views of Louisiana, Together with a Journal of a Voyage up the Missouri River in 1811, (Pittsburgh: Cramer, Spear and Eichbaum, 1814), 202.

After the Expedition

Although Charbonneau returned to the Hidatsa villages, traces of the rest of his life occur in journals and records from other frontier travelers.

1812: Worked for Lisa at Fort Manuel, south of present Mobridge, South Dakota.

1814: In a reprehensible move, Charbonneau persuaded mountain man Edward Rose to join him in buying female Arapaho captives from the Shoshones and selling them to trappers at upper Missouri posts.

1816: Traveled with traders to the upper Arkansas River, where he was captured by the Spanish and imprisoned at Santa Fe for forty-eight days.

1823: Worked for Joseph Brazeau, heading toward the Knife River Villages. Warring Arikaras ultimately diverted Charbonneau to Lake Traverse, near the South Dakota—Minnesota border.

1832: Interpreted for Prince Paul of Wurttemberg, Germany, when the Duke and his entourage toured the upper Missouri country. On this trip, Paul befriended Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, which resulted in the young man spending eight years in Europe as a guest of the Prince.

1833: Interpreted for Prince Alexander Philipp Maximilian of the Prussian principality Wied-Neuwied, whose upper Missouri traveling party included the artist Karl Bodmer. The prince wrote: “Charbonneau was absent again. This 75-year-old man is always running after women.”[4]Quoted from http://www.state.nd.us/arts/artist_archive/B/Bodmer_Karl.htm/. Charbonneau was still in his sixties, but blamed a life lived outdoors for his weathered appearance.

1834: Fort Clark trader F.A. Chardon recorded that “Old Charbonneau” cooked the Christmas Eve supper of “Meat pies, bread, fricassied pheasants[,] Boiled tongues, roast beef—and Coffee.” Chardon was factor, or superintendent, of this American Fur Company post that served the nearby Mandan and Hidatsa villages.

1838: His latest wife having died the previous year, Charbonneau took a fourteen-year-old Mandan bride.

1839: Superintendent of Indian Affairs (and former fur trader) Joshua Pilcher recorded that Charbonneau arrived in St. Louis from the Mandan villages, “1600 miles” away, “without a dollar to support him” and seeking pay for his work as a government interpreter among the Mandans. In 1837 the Mandans had been decimated by a smallpox epidemic that also killed about half of the Arikaras. Surviving Mandans had moved away from Fort Clark to the Hidatsa villages on Knife River.[5]www.state.nd.us/HIST/ftClark/ftClark2.html/. Some post-expedition information about Charbonneau has been drawn from Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark … Continue reading

Toussaint Charbonneau survived into his mid-seventies, outliving his friend William Clark, who died in 1838. A legal document from 1843 shows that Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was to receive $320 “from the estate of his deceased Father.”

Funded in part by a grant from the National Park Service, Challenge Cost Share Program

Related Pages and Encounters

Meriwether Lewis’s recitation of Charbonneau’s recipe for buffalo sausage, known as “white pudding,” serves not only as documentation of a unique frontier cuisine, but also as an example of the captain’s own brand of satire.

November 4, 1804

Meeting Charbonneau

Fort Mandan, ND Toussaint Charbonneau, a fur trader living at one of the Knife River villages, arrives at the Fort Mandan building site. Because he speaks French and Hidatsa and has two Shoshone wives, the captains hire him as an interpreter.

November 11, 1804

Charbonneau's buffalo robes

Fort Mandan, ND Toussaint Charbonneau and two Indian women bring buffalo robes. The enlisted men continue with construction, and Lewis calculates latitude.

November 20, 1804

Diplomatic complications

Fort Mandan, ND Three chiefs from the Ruptáre village say that the Sioux will punish the Arikaras if they follow the captain’s peace initiatives. Charbonneau brings a large load of meat and furs, and the captains move into their room.

November 21, 1804

Lining the chimneys

Fort Mandan, ND The backs of four chimneys are lined with river rock, and store rooms are organized. The river is clear of ice, and Clark reports spirits are high.

November 25, 1804

Hidatsa diplomacy

Fort Mandan, ND Lewis, both interpreters, and five men embark on a diplomatic mission to a Hidatsa village. Two Hidatsa chiefs come to Fort Mandan with similar intentions.

December 13, 1804

Trading for corn and beans

Fort Mandan, ND Sgt. John Ordway sends two men to Mitutanka to trade for food. Joseph Field kills two buffalo near Fort Mandan, and a trader from the North West Company visits.

December 18, 1804

Clark's Fort Mandan maps

Fort Mandan, ND Three visiting fur traders leave the fort, and Clark updates his maps using the geographic information obtained from them. Due to the cold, guard duty is shortened, and a buffalo hunt is canceled.

December 26, 1804

Seeking Charbonneau

Fort Mandan, ND A trader from the North West Company comes to the fort to hire Charbonneau as a translator. The day is pleasant, and Lewis plays backgammon.

January 3, 1805

Providing a safe refuge

Fort Mandan, ND Nine men go out bison hunting with small success. A Hidatsa husband is looking for his wife who has come to the fort seeking refuge.

January 11, 1805

A war medicine dance

Fort Mandan, ND Chiefs Posecopsahe (Black Cat) and The Coal visit the fort and spend the night. At Mitutanka village, several soldiers witness a war medicine dance.

January 13, 1805

Large Mandan hunting party

Fort Mandan, ND Clark estimates that half the Mandan population has formed a large hunting party and are heading down the river. Charbonneau tells Clark why Hidatsa Chief Le Borgne has kept his distance.

January 24, 1805

Cutting wood for coal

Fort Mandan, ND Interpreters Toussaint Charbonneau and René Jusseaume appear to have reconciled, hunters return empty-handed, and men cut wood to make charcoal.

February 10, 1805

Howard's court-martial

Fort Mandan, ND Joseph Field, a member of Clark’s hunting party, suffers frostbite. At Fort Mandan, Howard’s sentence of 50 lashes—given for climbing the back wall—is forgiven.

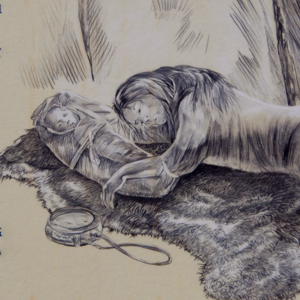

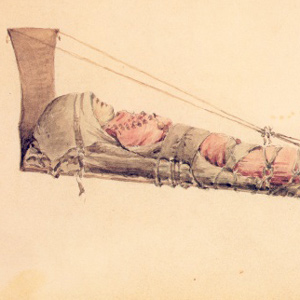

February 11, 1805

Delivering baby Charbonneau

Fort Mandan, ND After a tedious and painful labor, Sacagawea gives birth to her first baby, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. Clark, hunting about 40 miles to the south, heads back towards the fort.

March 7, 1805

Charbonneau's windfall

Fort Mandan, ND Toussaint Charbonneau returns with trade goods from the North West Company. An Indian child is given Rush’s Thunderbolts, a strong laxative.

March 12, 1805

Charbonneau quits

Fort Mandan, ND When Toussaint Charbonneau’s expectations cannot be met, his employment as an expedition interpreter comes to an end. Two men go to a Hidatsa village to trade for tobacco, and James Wilkinson tells Spanish officials to stop the expedition.

March 14, 1805

Charbonneau moves out

Fort Mandan, ND According to Sgt. Ordway, Toussaint Charbonneau moves outside the fort and is replaced as expedition interpreter by Joseph Gravelines. The men shell corn. In Washington City, Thomas Jefferson suggests a new expedition in the Southwest.

March 17, 1805

Charbonneau moves back

Fort Mandan, ND Toussaint Charbonneau apologizes to the captains, agrees to their terms of employment, and moves his things into a leather tent outside Fort Mandan.

April 7, 1805

Leaving Fort Mandan

The permanent party leaves Fort Mandan bound for the Pacific Ocean. They make it only as far as Mitutanka, one of the Knife River Villages. In the barge, the return party heads towards St. Louis.

April 13, 1805

The white pirogue's near miss

Below present Van Hook Arm, North Dakota, a sudden gust of wind hits the white pirogue with Charbonneau at the helm. In his panic, he turns the boat sideways to the wind and nearly turns it over.

April 18, 1805

Head winds

The Charbonneau family joins Clark on shore as the boats struggle against strong headwinds. Lewis takes a turn and sees buffalo wool and the golden pea. Camp is below present Williston, North Dakota.

May 9, 1805

Charbonneau's boudin blanc

Below present Fort Peck, Lewis worries as sandbars begin to crowd the river, and the Rocky Mountains are still not in sight. He also describes how Charbonneau prepares a white sausage—boudin blanc.

May 14, 1805

Two close calls

In present Eastern Montana, hunters take flight from a wounded grizzly and the white pirogue, steered by Toussaint Charbonneau, tips over. The captains call it a day and issue a ration of consoling grog.

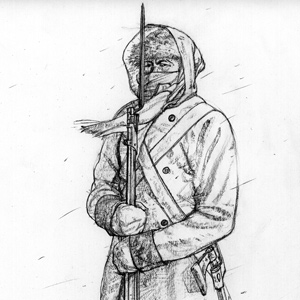

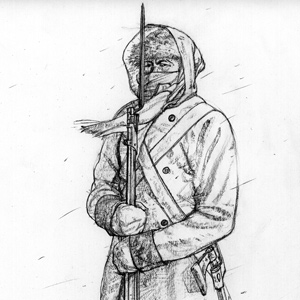

Charbonneau’s ultimate test of faith came as a boatman, on a day when he was at the helm of the white pirogue. After a sudden gust of wind, he panicked and turned the boat sideways to the wind, turning the boat over.

June 2, 1805

Marias River arrival

A grizzly bear chases Drouillard and Charbonneau, and Lewis with several hunters take several hides to cover the iron-framed boat. After towing the boats 18 miles, they reach the mouth of the Marias River.

June 15, 1805

Sacagawea deteriorates

Below the Great Falls of the Missouri, Sacagawea‘s health deteriorates, and Charbonneau asks her to return home. Several miles ahead, Lewis fishes and describes a prairie rattlesnake in minute detail.

June 19, 1805

Sacagawea relapses

Below the Great Falls of the Missouri, the men prepare for the portage and Sacagawea relapses. At the White Bear Islands, Clark determines he will find the best route to haul the heavy dugout canoes.

June 22, 1805

Portaging the first dugout

A large group hauls the first dugout canoe around the Great Falls of the Missouri. The wagon needs frequent repairs, and after dark, they abandon the heavy boat and hike the remaining ½ mile.

June 25, 1805

Two more dugouts up the hill

Below the Falls of the Missouri, Clark enjoys a cup of coffee. At the upper camp, Drouillard and Frazer bring in 800 pounds of dried meat and in Washington City, Jefferson shares news of the Expedition.

June 26, 1805

Suet dumplings

Two dugouts are carted around the Falls of the Missouri with the help of sails. Whitehouse suffers from heat exhaustion and as a special treat, Lewis makes suet dumplings for the tired crews.

July 3, 1805

Sewing and hunting

Above the Falls of the Missouri, Lewis laments they will soon be leaving buffalo country, and Sgt. Gass and Pvt. McNeal visit the falls. Loose stitches leave holes in the hides covering the iron-framed boat.

July 13, 1805

Leaving the Great Falls

Lewis and the last of the crew leave the White Bear Islands above the Great Falls of the Missouri. At the canoe-making camp near present Ulm, Clark has “an emensity of meat” dried to make pemmican.

July 26, 1805

Charbonneau nearly drowns

Clark surveys the Jefferson River and saves Charbonneau from drowning. Still on the Missouri, Lewis moves the boats past “Howard” Creek where the main party suffers from barbed grass and prickly pears.

August 4, 1805

Extreme labor and fatigue

Forks of the Jefferson, MT Clark notes how hard the men must work to move the canoes up the shallow and swift Jefferson River. Ahead, Lewis ponders the many rivers, and chooses the Beaverhead River.

August 5, 1805

The wrong river

Forks of the Jefferson, MT At the forks of the Jefferson River, the main party fails to see a note left by Lewis and takes the canoes up the wrong river. The men ask to abandon the boats. Ahead, Lewis and Drouillard try to find Shoshones.

August 14, 1805

Asking for Shoshone help

Lemhi River, ID and Rattlesnake Cliffs, MT At a village on the Lemhi River, Lewis asks for the use of Cameahwait’s horses and people to bring the expedition’s baggage over the Continental Divide. Back on the Beaverhead River, the men ache from having to haul the canoes over rocks in the cold river.

August 16, 1805

Too many worries

Fortunate Camp, MT When Clark fails to arrive at the forks of the Beaverhead, Lewis worries about the fate of the expedition. The Lemhi Shoshones worry that they have been led into a trap. The main party comes to within a day’s travel of Fortunate Camp.

August 18, 1805

Searching for a navigable river

Fortunate Camp and Red Butte, MT Clark, the Charbonneau family, several men, and many Lemhi Shoshone Indians cross Shoshone Cove on their way to find a navigable branch of the Columbia River. At Fortunate Camp, Lewis has a birthday meditation.

August 24, 1805

Leaving Fortunate Camp

Salmon River, ID and Shoshone Cove, MT Lewis barters for three horses and a mule, and Charbonneau buys a horse for Sacagawea. With the help of Shoshone women, they start carrying baggage over the continental divide. Clark considers three alternate plans for reaching the Pacific Ocean.

August 25, 1805

A change of plans

Tower Creek, ID and Shoshone Cove, MT Lewis is shocked to learn of a change in Shoshone plans. Clark returns to his Salmon River camp of 21 August 1805.

August 27, 1805

Flag ceremony

Lemhi River Valley, ID After a flag ceremony at the Upper Lemhi village, Lewis commences horsetrading. In the evening, the Lemhi Shoshones dance and sing. Further down the Lemhi River, Clark’s group hunts while waiting for Lewis to arrive.

October 27, 1805

Taking Indian vocabularies

Fort Rock, The Dalles, OR Visiting Indians give the captains an opportunity to compare the languages and customs of the Sahaptian and Chinookan Peoples living above and below The Dalles of the Columbia.

November 17, 1805

A disappointing cape

Station Camp near Chinook, WA Having explored Cape Disappointment, Lewis returns to Station Camp without finding any trading ships. Despite his report of a very bad road, several men volunteer to go there with Clark tomorrow.

January 31, 1806

Stopped by ice

At Fort Clatsop near present Astoria, Oregon, a hunting party is stopped by river ice. Pvt. Joseph Field returns from the salt works, and Charbonneau brings Lewis a new bird—the varied thrush.

April 17, 1806

A struggle to buy horses

At the Wishram villages on the north side of Celilo Falls, Clark and Charbonneau struggle to buy horses. At Fort Rock, Lewis remarks on the rich verdure and prepares several plant specimens.

April 22, 1806

Charbonneau's horse accident

Charbonneau‘s horse bolts causing several items to fall off. They are hidden by watchful Wishram Indians. The march continues by foot, horse, and dugout canoe to a spring near present John Day dam.

April 23, 1806

Friendly Tenino village

To continue up the Columbia, most of the members must walk over large sand dunes. At present Rock Creek, they reach a friendly Tenino village of Wah-how-pum. The day ends with smoking and dancing.

April 28, 1806

Yelleppit brings a horse

Across from the Walla Walla River, talks begin with Sacagawea and Charbonneau as interpreters. Yelleppit brings Clark a horse, Clark gives medical aid, and Pvt. Frazer buys ten fat dogs for consumption.

May 5, 1806

Clark's eye water magic

On the Clearwater River, the Captains discover that Clark’s eye water can be traded for food and horses. A Nez Perce man tosses a puppy at Lewis who fails to see the humor. Camp is at Colters Creek—present Potlatch River.

May 19, 1806

Caring for horses

In the hills surrounding Long Camp, hunting remains poor, so they cross the Clearwater to buy food from the Nez Perce. Numerous Nez Perce come to Clark for medical treatment, and the horses are exercised.

May 30, 1806

Two river disasters

On the Snake River, Ordway buys several salmon. At Long Camp, two men lose the new canoe and three blankets trying to cross the flooding Clearwater River. The captains attend to an ailing Nez Perce chief.

May 31, 1806

Classifying grizzlies

At the Nez Perce fishing camp, Ordway begins the journey back to Long Camp. Confused by their many colors, Lewis decides to follow the Nez Perce system that classifies all grizzlies as a single species.

June 1, 1806

Clarkia and rough wallflower

Clark mentions a plan to divide forces after reaching Travelers Rest, and Drouillard is sent to find Nez Perce men to guide them. Lewis discusses the Clarkia flower and prepares two more plant specimens.

June 7, 1806

New ropes and bags

In anticipation of moving from Long Camp to the Weippe Prairie, five men cross the Clearwater River to buy ropes and bags. A Nez Perce chief gives Pvt. Frazer, who has learned their language, a horse.

July 3, 1806

Splitting up

Lewis heads north spending most of the day rafting baggage across present Clark Fork west of Missoula, Montana. Clark’s group heads south along the west side of the Bitterroot River.

July 18, 1806

Smoke signals

On the Yellowstone, Clark sees smoke and suspects that the Crows have discovered them. To the north, Lewis arrives at the Marias River, Gass visits Lower Portage Camp, and Ordway nears the Falls of the Missouri.

July 19, 1806

Beached dugouts

On the Yellowstone, Clark finds trees for making canoes and attends to Pvt. Gibson’s wound. Lewis moves up the Marias River, while at the Great Falls of the Missouri, Sgts. Ordway and Gass beach the dugouts.

July 20, 1806

Hopes dim and rise

Lewis sees the Marias watershed and hopes for extending the Louisiana Territory dim. Clark builds dugouts on the Yellowstone and hopes Hugh Heney will accept a commission. Ordway and Gass are at the Falls of the Missouri.

July 21, 1806

A spate of missing horses

On the Yellowstone, half of Clark’s horses appear to be stolen by Crow Indians. Above the Falls of the Missouri, missing horses delay the portage. On the Marias, Lewis turns up Cut Bank Creek.

July 22, 1806

Lewis's great disappointment

Detachments at the Yellowstone River Canoe Camp and Great Falls of the Missouri search for missing horses. Lewis sees that Cut Bank Creek does not go north and stops to hunt and make celestial observations.

August 15, 1806

Broken promises of peace

Knife River Villages, ND The captains hear of several broken promises of peace among tribes they had worked with on the outward journey. Colter asks to leave the expedition so that he can go back west with two fur trappers.

August 16, 1806

Parting gifts

Knife River Villages, ND Mandans gift more corn than the expedition boats can carry. As parting gifts, the swivel gun is given to Hidatsa Chief Le Borgne and the blacksmith tools to Charbonneau. Sheheke (Big White) agrees to go to Washington City.

August 17, 1806

An offer to raise Jean Baptiste

Hensler, ND The expedition heads down the Missouri River taking leave of the Hidatsas, Mandans, John Colter, and the Charbonneau family. Clark invites the latter to come to St. Louis and makes arrangements to raise Jean Baptiste Charbonneau.

August 20, 1806

"My dancing little boy"

Pollock, SD After morning rain, the expedition sets out early paddling about eighty miles. Clark notices the river has changed in many places. Clark writes a letter to Charbonneau offering him several job prospects and repeats his willingness to raise his “little dancing boy.”

The Charbonneaus in St. Louis

by Robert J. Moore

In 1809, Toussaint, Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste Charbonneau traveled to St. Louis. Jean Baptiste’s baptism began a new era in his life, is father would try to become a farmer, and Sacagawea would become sickly.

Notes

| ↑1 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854; 2nd ed.; 2 vols. (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:369. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jackson, Letters, 1:315. See also on this site Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. |

| ↑3 | Henry M. Brackenridge, Views of Louisiana, Together with a Journal of a Voyage up the Missouri River in 1811, (Pittsburgh: Cramer, Spear and Eichbaum, 1814), 202. |

| ↑4 | Quoted from http://www.state.nd.us/arts/artist_archive/B/Bodmer_Karl.htm/. |

| ↑5 | www.state.nd.us/HIST/ftClark/ftClark2.html/. Some post-expedition information about Charbonneau has been drawn from Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 107, 134, 136, 138, 171-72. |