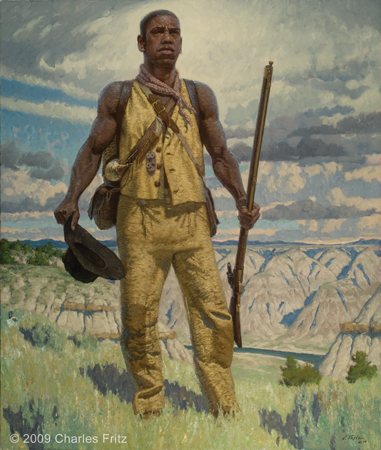

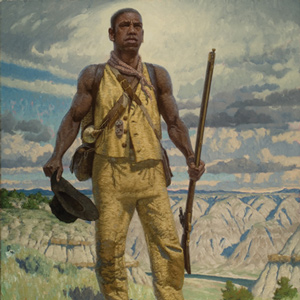

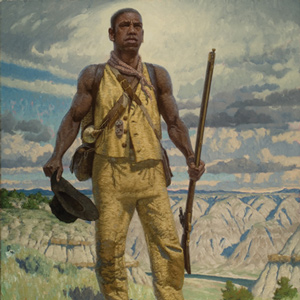

Glimpsing Freedom: York’s Journey with the Corps of Discovery

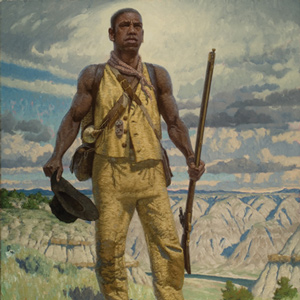

38″ x 32″ oil on canvas

© 2009 by Charles Fritz. Used by permission.

Heroes at Odds

Two years after the conclusion of the historic Lewis and Clark Expedition across the Louisiana Purchase and the disputed Oregon country of the Pacific Northwest, York and his enslaver, the Virginia-born patrician William Clark, were at odds. Fully aware of the fame, national celebration, and material compensation that redounded from the expedition, York was demanding that he be freed as a reward for his participation.[1]Emory and Ruth Strong, Seeking Western Waters: The Lewis and Clark Trail from the Rockies to the Pacific, ed. Herbert K. Beals (Oregon Historical Society: 1995), 126. The authors note that all of the … Continue reading He had evidently not only assessed the expedition’s national importance, but also the value of his contribution to its success. He was not too humble or too debased in his estimation of himself to insist upon his freedom.

What further underlay his insistence was his desire to be reunited with his wife, who was enslaved in Louisville, Kentucky, and from whom he was separated when Clark, after the expedition, left Kentucky for St. Louis, Missouri. Clark, insulted, refused, giving York leave to visit her for “a fiew weeks,” but ordering him to return. York even offered to stay in Louisville permanently and hire himself out, sending his earnings to Clark.

But the new national hero, evidently believing himself extraordinarily indulgent, was adamant, even indignant. “if any attempt is made by York to run off, or refuse to provorm his duty as a Slave, I wish him Sent to New Orleans and sold, or hired out to Some Sevare Master untill he thinks better of Such Conduct,” Clark wrote in November 1808 to his eldest brother, Jonathan, who lived in Louisville and could supervise York’s stay there. “I do not wish him to know my determination if he conducts himself well.”[2]James J. Holmberg, “‘I Wish You To See & Know All’: The Recently Discovered Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 18, No. 2, (November 1992), … Continue reading

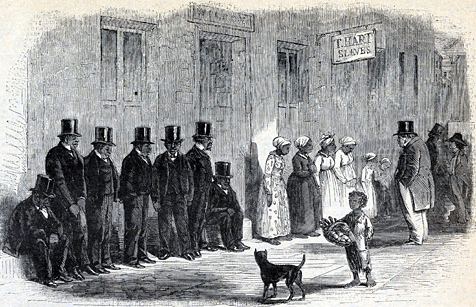

The Arrogance of Tyranny

Clark’s attitude could perhaps have been construed as charitable considering the norm. “Though slavery is thought by some, to be mild in Missouri, when compared with the cotton, sugar and rice growing states, yet no part of our slaveholding country, is more noted for the barbarity of its inhabitants, than St. Louis,”[3]William Wells Brown, Narrative of William Wells Brown, A Fugitive Slave, Written By Himself, in Puttin’ On Ole Massa: The Slave Narratives of Henry Bibb, William Wells Brown, and Solomon Northrup, … Continue reading wrote William Wells Brown, an Afrikan abolitionist born in 1814 on a plantation near Lexington, Kentucky, who spent his first 20 years enslaved mainly in St. Louis.

It may well be that Clark grossly underestimated York’s awareness of his master’s intentions, just as he underestimated York’s sense of his own humanity, for York was unrelenting on the matter of his emancipation. The restive Afrikan “has got Such a notion about freedom and his emence Services [on the expedition], that I do not expect he will be of much Service to me again,” Clark grumbled. “I do not expect much from him as long as he has a wife in Kenty.”

Even after York returned from Louisville in May 1809, Clark complained he was “of verry little Service to me, insolent and Sulky.” His solution was to beat him, vainly (as it turned out) hoping York’s “Severe trouncing” would correct the inconceivable error of considering himself a human being whose interests were more important than those of his enslaver. But even that was not enough. Among the punishments an incredulous Clark inflicted in his attempt to reform York’s seemingly “incorrigible” attitude were jailing and (perhaps in resignation) banishment—hiring York out in Kentucky, including to Jonathan’s plantation, as well as to a “cruel” enslaver.[4]Holmberg, 8–9.

The Sweetness of Freedom

Clark was completely oblivious of the fact that, as Mary Prince, an Afrikan woman enslaved in the Bermuda, West Indies, would remark in 1831: “All slaves want to be free . . . to be free is very sweet. . . . I have been a slave myself . . . and I know what slaves feel. . . . The man that says slaves be quite happy in slavery—that they don’t want to be free . . . that man is either ignorant or a lying person.”[5]Mary Prince, History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave. Written By Herself, in The Classic Slave Narratives, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (New York: Mentor, 1987), 214.

That the breach had finally surfaced was obviously very much of a shock to the Kentuckian and adventurer, who at 38 had grown accustomed to the apparent docility and devotion of his “slave.”[6]Betts, 106–08. Betts suggests the degree of freedom York experienced during the expedition made the conditions of enslavement, upon return to the United States, unbearable. Such subjugation had clearly been a tradition for at least three generations in Clark’s family. Believed to be only a few years younger than Clark, York had been his body servant for virtually all of Clark’s life. Likewise, York’s father, also named York, had been enslaved by Clark’s father, John, who had likely inherited the senior York from Clark’s grandfather in 1734.

Upon his father’s death in July 1799, Clark inherited eight enslaved Afrikans, including York, his parents, “old York” and Rose, and York’s younger sisters, Nancy and Juba, along with livestock, plantation equipment, a still, and thousands of acres of land in Kentucky near Louisville, and across the Ohio River in the Illinois country.[7]Ibid., 84–7.

A Strong Sense of Himself

Perhaps York’s independence of mind arose from a strong sense of himself. He was, after all, a figure of great size and physical strength, a fact about which he must have taken some pride because it—along with his very dark black skin—proved fascinating to many of the native peoples and, at times, a critical instrument of diplomacy for Captain Meriwether Lewis‘s and Lieutenant William Clark’s nearly two-and-one-half-year, 8,000-mile exploration of America’s uncharted lands.[8]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 9:85.

To the Arikaras (in what is now South Dakota), who had never seen Afrikans, “York was a sensation,” about whom, because of his (to them) unusual appearance, they could not determine if he were “man, beast, or spirit being.”[9]Holmberg, loc. cit. As Clark’s “companion,” he was also accustomed to more independent action than was the lot of a mere chattel slave consigned to an existence of terror, torture, hunger and back-breaking labor. He was also enormously resourceful and skilled as a hunter and an outdoorsman, a fact to which both Lewis and Clark attest, if only implicitly, in the various assignments given him.[10]Strong, 137.

Further, that one of his sisters bore an Afrikan name may be an indication of the strength of his parents’ inner sense of an independent identity, something they may have conveyed to him during his childhood. Juba, a corruption of Adjua, originates from the Akan peoples of what is now Ghana, West Afrika. It was a name given to a girl born on Monday.[11]Joseph E. Holloway and Winifred K. Vass, The African Heritage of American English (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993), 81. The authors note that “African names common in … Continue reading

A Mystery in History

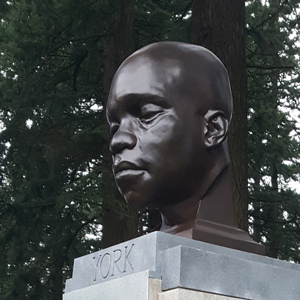

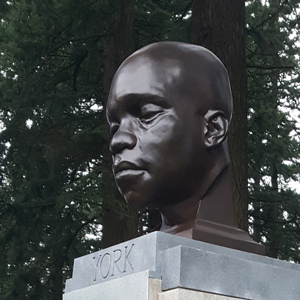

Despite his enslaved status, York’s membership in the legendary Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery, a major event in American history, should have garnered him considerable notoriety. Yet the nineteenth-century Afrikan historian William Wells Brown did not list him among the 53 Afrikan notables in The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (1863) nor among the 80 great men and women in The Rising Sun; or, The Antecedents and Advancement of the Colored Race (1874).

Although he was one of initially about 48, and eventually 33, people who constituted the chiefly military 1804–06 expedition commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson to advance America’s commercial, scientific, geographical, and diplomatic interests, he has left no record of his own words and thoughts to posterity.

In an age when formerly enslaved Afrikans wrote more than 100 book-length narratives of their experiences in the decades before the end of the Civil War, what is known about him comes only through the thoughts, observations, and biases of those who enslaved him or to whom he was subordinate in a white supremacist and enslaving society of caste.[12]Insofar as the “slave narratives” were produced by Afrikans who had freed themselves, it may be conjectured that York did not leave a record of his thoughts and experiences because he was never … Continue reading

Clark’s Unrepentant Captive

Predictably, York’s steadfastness in affirming his humanity made him unpopular with Clark’s family in Louisville. According to a September 1809 letter from his brother, Edmund, “neither he nor anyone else [in the family] liked York.” Clark himself seemed to have despaired of overcoming York’s resistance, exclaiming “I do not . . . cear for Yorks being in this Country [St. Louis]. . . . I do not wish him again in this Country untill he applies himself to Come and give over that wife of his.”[13]Holmberg, 8–9. York, evidently, never returned.

In the end perhaps Clark resigned himself to the realization that his recrimination, punishments, and banishment would not prevail upon York, for he is alleged to have freed him some six or more years later.[14]Betts, 118. In the interim Clark attempted to compel York’s submission. By November 1815 Clark and his nephew, John Hite Clark, had “entered into a business agreement to purchase a wagon and team to be operated in and around Louisville,” forcing York to be its driver.[15]Holmberg, 8–9.

Still, when all is said and done, York’s fate remains unknown. The story is told that Clark eventually freed York, set him up in a drayage business similar (if not identical) to the one he and his nephew had begun, and that York reportedly hauled goods between Nashville, Tennessee, and Richmond, Kentucky.

Further, according to notes the famed writer Washington Irving took of a conversation he had with Clark in September 1832, “York did not fare well in his business, lost it, and eventually attempted to return to St. Louis and to Clark, but died in Tennessee of cholera before doing so.”[16]Ibid.

But York’s quest for freedom was an offense to Clark’s racism that made him deeply bitter toward his captive. Hence, the idea that Clark freed York, established him in a business similar to the one he had begun with his nephew, and that after failing in it York eventually gave up the idea of being free, and was anxious to return to St. Louis and to Clark’s service and good graces, seems all too pat.[17]Betts, 119-122.

It may be much more likely that York was never freed, and that he labored, unrepentant, in Clark’s and his nephew’s freighting business until he died.

Articles

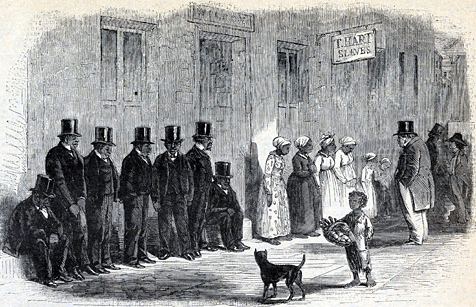

Clark, York, and Slavery

by James J. Holmberg

The mistake should never be made that the two men were friends. They were master and slave, owner and property, superior and inferior. As close as that relationship was for the many years and countless miles they were by each other’s side, for all the dangers and hardships they shared their relationship always was based on William as master and York as servant.

York’s Fallout over Freedom

by Joseph A. Mussulman

It is remarkable that we have no record of York’s words and thoughts. Insofar as the nineteenth century “slave narratives” were produced by Africans who had freed themselves, it may be conjectured that York did not leave a record of his thoughts and experiences because he was never freed.

Even if someone had invited him to sing them, it is probable that he as well as many of his listeners would have considered it ill-mannered if not illegal to do so.

Selected Journal Excerpts

April 7, 1804

Capt. Stoddard's ball

Clark, Lewis, and York travel to St. Louis to attend a formal dinner and ball hosted by Captain Amos Stoddard, new Commandant of Upper Louisiana. Sgt. Ordway is left in charge at Camp River Dubois.

June 20, 1804

York is injured

Whitehouse reports hard rowing and Ordway notices crab apple trees as they work their way to a camp near present Lexington, Missouri. York is injured when one of the men throws sand in his eyes.

August 24, 1804

Bluffs on fire

Goat Island, NE The expedition passes a burning bluff that some call the Ionia Volcano. York kills an elk, and the captains express curiosity about a small mound in the prairie, present Spirit Mound, that the Indians fear.

August 25, 1804

Visiting Spirit Mound

Spirit Mound, SD The captains take a large party to explore Spirit Mound. Instead of finding devils, they suffer from excessive heat and witness birds eating swarms of flying ants.

September 9, 1804

Gangs of buffalo

Below Whetstone Bay, SD Clark and York walk the shore. They see hundreds of buffalo throughout the day, and Clark directs York to kill one.

October 9, 1804

Tabeau and Too Né

Arikara village Sawa-haini, SD The Arikara council is delayed by weather. The captains meet several key people including Pierre-Antoine Tabeau and Chief Too Né. York fascinates the Arikara who apparently have never seen a black man before.

October 10, 1804

An Arikara council

Arikara village Sawa-haini, SD Above present-day Mobridge, a council with the Arikaras is held, and the standard speeches and gifts are given. Clark appears a bit upset when York hams it up for the Indians.

October 15, 1804

Arikara exchanges

Fort Yates, ND As they travel past various hunting camps, the men trade with the Arikaras. A young Indian girl traveling with the boats is summoned to shore.

October 28, 1804

Council postponed

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND The Indian council planned for today is postponed due to high winds. Nearby Indians visit none-the-less, and Posecopsahe (Black Cat), Clark, and Lewis look for a place to build winter quarters.

December 8, 1804

Frostbitten hunters

Fort Mandan, ND On a day that starts at 12 below zero, the hunters return to Fort Mandan with buffalo meat. Several men have frostbite—one badly on the feet. York is also “touched”.

January 1, 1805

A new year at Fort Mandan

Fort Mandan, ND New Year’s day is celebrated with cannon fire and several men are allowed to visit a nearby Mandan village to celebrate and dance. Clark orders York to dance. The day is warm with rain but the night is cold and snowy.

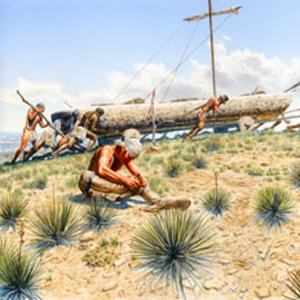

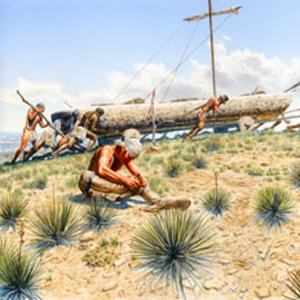

June 22, 1805

Portaging the first dugout

A large group hauls the first dugout canoe around the Great Falls of the Missouri. The wagon needs frequent repairs, and after dark, they abandon the heavy boat and hike the remaining ½ mile.

June 29, 1805

A flash flood

Hail and rain disrupt the portage around the Falls of the Missouri. Baggage is left on the plain, men are bruised and bloody, and Sacagawea and her baby are nearly swept away in a flash flood.

Of all the near-calamities the Corps of Discovery experienced, none was more dire than the one that occurred on 29 June 1805 in a normally dry ravine a short distance above the Great Fall. The principals were Charbonneau, Sacagawea, Jean Baptiste, York, and William Clark.

July 7, 1805

Waiting on the iron-framed boat

Another day is spent above the Great Falls of the Missouri waiting for the iron-framed boat cover to dry. Several men make leather and sew new clothes, and Clark gives York a dose of tarter emetic.

July 20, 1805

Smoke signals

Traveling in the Helena Valley, Clark sees smoke—likely Indians warning others of their presence. Clark’s feet are blistered, and York is “nearly tired out”. Lewis commandeers the boats up the Missouri.

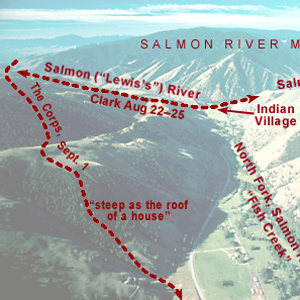

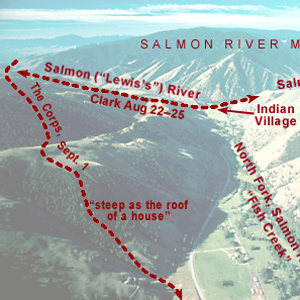

September 1, 1805

Up the North Fork Salmon River

North Fork Salmon River, ID People and horses climb out of Tower Creek, crosses high hills, descend to the North Fork Salmon River, and encamp near present-day Gibbonsville, Idaho.

October 26, 1805

Refuge at Fort Rock

Fort Rock, The Dalles, OR Men are sent out to hunt and gather pine pitch to seal the leaking canoes. Two chiefs and fifteen warriors cross the river to visit and share food, and Clark enjoys fresh steelhead cooked in bear oil. The fleas are bothersome.

November 17, 1805

A disappointing cape

Station Camp near Chinook, WA Having explored Cape Disappointment, Lewis returns to Station Camp without finding any trading ships. Despite his report of a very bad road, several men volunteer to go there with Clark tomorrow.

July 14, 1806

Sacagawea knows a way

At the Great Falls of the Missouri, Lewis has the wheels and iron-framed boat dug up. Clark mires in Gallatin River swamps before finding an old bison trace. Sgt. Ordway‘s group paddles to Yorks Islands.

Notes

| ↑1 | Emory and Ruth Strong, Seeking Western Waters: The Lewis and Clark Trail from the Rockies to the Pacific, ed. Herbert K. Beals (Oregon Historical Society: 1995), 126. The authors note that all of the expedition’s participants except York, the Lemhi Shoshone woman Sacagawea, and her infant son, Baptiste, were given land grants and other remuneration after the journey. It is highly unlikely, given the closeness of York’s relationship to Clark, that York was unaware of this. See also Robert B. Betts, In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific with Lewis and Clark (Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1985), 109-110. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | James J. Holmberg, “‘I Wish You To See & Know All’: The Recently Discovered Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 18, No. 2, (November 1992), 7-8. |

| ↑3 | William Wells Brown, Narrative of William Wells Brown, A Fugitive Slave, Written By Himself, in Puttin’ On Ole Massa: The Slave Narratives of Henry Bibb, William Wells Brown, and Solomon Northrup, ed. Gilbert Osofsky (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1969), 185-6. |

| ↑4 | Holmberg, 8–9. |

| ↑5 | Mary Prince, History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave. Written By Herself, in The Classic Slave Narratives, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (New York: Mentor, 1987), 214. |

| ↑6 | Betts, 106–08. Betts suggests the degree of freedom York experienced during the expedition made the conditions of enslavement, upon return to the United States, unbearable. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 84–7. |

| ↑8 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 9:85. |

| ↑9 | Holmberg, loc. cit. |

| ↑10 | Strong, 137. |

| ↑11 | Joseph E. Holloway and Winifred K. Vass, The African Heritage of American English (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993), 81. The authors note that “African names common in the eighteenth century were Sambo, Quash [Kwesi/Kwasi], Mingo, and Juba. The most widely used names were Cuffee (Kofi) and Cudjoe [Kodjo] for males and Abba and Juba for females.” See also Betts, 86; William Wells Brown, The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (New York: Thomas Hamilton, and Boston: R. F. Wallcut, 1863) and The Rising Sun; or, The Antecedents and Advancement of the Colored Race (Boston: A.G. Brown and Company, Publishers, 1874). |

| ↑12 | Insofar as the “slave narratives” were produced by Afrikans who had freed themselves, it may be conjectured that York did not leave a record of his thoughts and experiences because he was never freed. Certainly, he would not have been unaware of the significance of his story, nor undesirous of telling it. |

| ↑13 | Holmberg, 8–9. |

| ↑14 | Betts, 118. |

| ↑15 | Holmberg, 8–9. |

| ↑16 | Ibid. |

| ↑17 | Betts, 119-122. |