No sod, no sign, no cross nor stone,

But at his side a cactus green

Upheld its lances long and keen;

It stood in sacred sands alone,

Flat-palmed and fierce with lifted spears;

One bloom of crimson crowned its head,

A drop of blood, so bright, so red,

Yet redolent as roses’ tears.

Prosaic Prickly Pear

Figure 1

Linnaeus in English

Image from the Metcalf Collection at North Carolina State University. Internet Archive.

Title page of Volume Five of the first English edition (1802) of Carl Linnaeus‘s Systema Naturæ

The seven volumes of the first edition of the Systema Naturæ, translated into English by the British naturalist William Turton, were published in London between 1802 and 1806. Volume five alone listed 180 species of “Vegetables,” including 28 species of Linnaeus’s genus Cactus, divided into four groups. The first group contained two species, C. mamillaris and C. Melocactus (Figure 3).

The second group included Cactus repandus, commonly called Cereus (Latin for “torch,” from its use as such by Indians of its native habitat, Jamaica); it was well known among physicians in Europe and America for its homeopathic uses. The fourth group included Cactus opuntia which is a synonym for Opuntia humifusa, (Raf.) Raf., the eastern pricklypear (Figures 5 & 6). Group four also contained C. ficus-indica (Figure 4, also known as Barbary fig) and C. coccinellifer, (now C. cochenilliferus L., Opuntia cochenillifera (L.) Mill, or Nopalea cochenillifera (L.) Salm-Dyck.).

There is no evidence that Meriwether Lewis ever saw Turton’s translation. At first it failed to attract much attention in the United States, possibly because most people seriously interested in botany then were fluent in Latin.[1]Charles Willson Peale mentioned Turton’s translation in a letter to Jefferson dated 3 November 1805. Jefferson included it in a list of books he recommended to his friend George Wythe. … Continue reading In any case, Miller’s Illustration of the Termini Botanici of Linnaeus would have been more useful to Lewis than the Swedish scientist’s already outdated system.

Few poets have yet been inspired by a cactus. Not that one or two haven’t tried, such as the eccentric American “Poet of the Sierras,” Joaquin Miller. Walt Whitman gave the plant a brief nostalgic nod in his reflective “Longings for Home,” from Leaves of Grass. But even Joyce Kilmer never claimed to have seen a poem as lovely as a prickl ypear. The ancient bards didn’t even have a chance at it either, for all members of the large family of plants now known as Cactaceae (kak-TAY-see-eye) are native strictly to the Americas, and were never seen in any other part of the world until Columbus returned to Portugal with some samples after his second voyage to the West Indies. Soon thereafter, explorers and other travelers began to nurse more specimens of the prickly curiosity across the Atlantic to European gardeners who had the patience to learn how to keep them from freezing or drowning in a colder and wetter climate.

By the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, most naturalists were aware that all members of the family Cactaceae were native to the Americas, but no one knew how many species, if any, would be found along the upper Missouri and lower Columbia Rivers. And few people cared, at least in the U.S.

Until the end of the 19th century, explorers of the Western Hemisphere mentioned cacti only incidentally, if at all. Just one species bore the respectability of the commercial nexus, the cochineal nopal cactus, which came to be known by botanists as Opuntia cochinillifera or, as Lewis once termed it, “the cockineal plant.” It was useful for the breeding of the cochineal insects that produced valuable red dye. But they were native to the island of Jamaica, and to the vicinity of Oaxaca, Mexico.

The so-called eastern prickly pear, Opuntia humifusa (Figures 4, 5), caught the attention of one of the earliest explorers of North America. In 1588 the English mathematician and astronomer Thomas Hariot (1560-1621) sailed to Roanoke Island off the coast of North Carolina. There he found “Metaquesunnauk a kinde of pleasaunt fruite almost of the shape & bignes of English peares, but that they are of a perfect red colour as well within as without. They grow on a plant whose leaves are verie thicke and full of prickles as sharpe as needles.”[2]Thomas Hariot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (London, 1588). Metaquesunnauk was an Algonquian word for the fruit of several prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) Hariot also … Continue reading He also heard of, but did not himself see, the Opuntia cochinillifera that he was told was cultivated in the West Indies.

In 1792, twelve years before the Lewis and Clark Expedition began, the Scottish naturalist Archibald Menzies (1754-1842), who accompanied Captain George Vancouver on his five-year circumnavigation of the globe, found some “Cactus opuntia” on the coast of California near today’s Santa Barbara, and later came upon a dwarfed variety of it on the sandy shore of Protection Island, opposite Nanaimo in southeastern Vancouver Island.[3]See the full text of Menzies’ journal of Vancouver’s voyage, April to October 1792, at https://archive.org/stream/menziesjournalof1792menz/menziesjournalof1792menz_djvu.txt. Lewis might have been interested in those discoveries, but they were not mentioned anywhere in Vancouver’s narratives that were published in 1801.

What hath God wrought?

This naturally spineless cladode and reddish-brown fruit of Opuntia ficus-indica, familiarly known among Mexicans as well as Latinos in the U.S. as nopales, or cochineal nopal cactus, was purchased at a supermarket in Anchorage, Alaska. Nopales have a flavor that has been compared with green beans, and are nutritious as a source of fiber and several vitamins, including A and C.

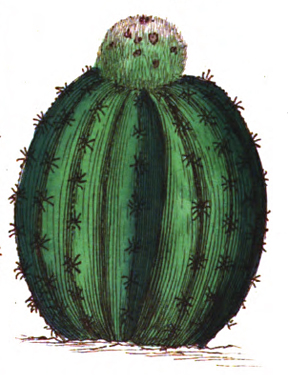

Figure 3

Cactus melocactus . . . of a globular form

Melon Thistle, or melon cactus

J. Miller, An Illustration of the Termini, Botanici of Linnaeus (1789), München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Google Books, accessed 23 April 2010.

As Figure 7 in Plate 9 of Miller’s Illustration of the Termini Botanici, this drawing merely illustrated a truncus angullatus (a trunk or stem having symmetrical angles or ribs in the horizontal cross-section) but is not discussed further. As Figure 8 in Plate 41, the same image is referred to as “Cactus melocactus,” and serves to illustrate pubescence, or woolly clusters of simple (not divided) hairs now called glochids (Figure 14).

In his Preface, Miller justified his omission of certain of “the more rare and curious Exotics,” implicitly the Cactaceae, which had become extremely popular with gardeners. “Though many of those Exotics often Flower in this Climate,” he explained, “few ever attain to the Maturity that is requisite for producing Fruit or Seeds; and without arriving at this Stage of vegetative Perfection, it is impossible to copy from Nature the Delineation of the Parts which alone are characteristic of the Species.”

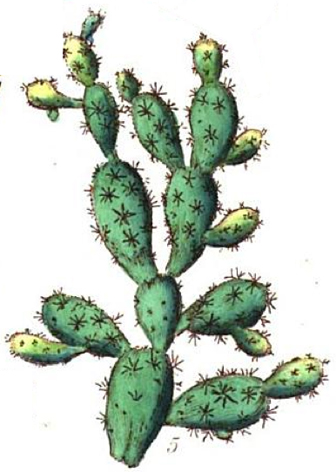

Figure 4

Cactus-tuna, Indian Fig, or Barbary Fig

Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill.

Courtesy of Google Books.

This drawing by John Miller (c. 1715-1790), a famous English illustrator of botanical subjects, appeared in his Illustration of the Termini Botanici of Linnaeus (1789), a copy of which is believed to have been in the Expedition’s small reference library.[4]Donald Jackson, “Some books carried by Lewis and Clark,” Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, 16 (Oct. 1959), 3–13. It was the companion volume to Miller’s Illustration of the Sexual System of Linnaeus (1779), which was also in the library. As Figure 5 in Plate 14, identified as Cactus- tuna—tuna being the Spanish synonym for prickly pear—or Opuntia, or Indian Fig, Miller’s drawing served to illustrate a Truncus articulatus—a jointed trunk or stem. As such, it may have been of passing interest to Meriwether Lewis, although he never mentioned having consulted Miller’s book.

The Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill.,[5]The specific epithet ficus-indica means “fig of the [West] India.” The initial L. stands for Linnaeus, who published the first taxon of it; Mill. stands for Philip Miller (1691–1771), … Continue reading often called Barbary fig, is still the most widely cultivated of all species of cactus, chiefly in Mexico, Central and northern South America. Lewis probably would not have seen any of this species en route; today it grows no farther north than southern California and in a few isolated locations in extreme southern Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Georgia, Florida and North Carolina.

Meanwhile, as the art of domestic gardening sifted down from the princely realms of European society to the wealthy new class of industrialists, cacti were slowly introduced as “exotics” in some of their gardens, too. In 1735 the prominent Scottish gardener Philip Miller (1691–1771) published the first abridged edition of his Gardener’s Dictionary,[6]Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit and Flower Garden, as also the Physick Garden, Wilderness, Conservatory, and Vineyard, … Continue reading in which he briefly described two varieties of Melocactus (melon-shaped cactus; see Figure 3) which he had seen in European gardens.

Then, following a detailed and instructive analysis of the challenges involved in importing cacti from the West Indies into the cooler and wetter climate of the British Isles, Miller observed: “These Plants are preserved with great Care by such as are curious in Exoticks, they being of the most uncommon and wonderful Structure, greatly differing from any thing in the vegetable Kingdom, of European Growth, insomuch that many Persons, at the first Sight of these Plants, have supposed them not natural Productions, but rather some artful Contrivance to amuse People.” The fruits of these cacti were “extremely agreeable” to people in the West Indies, he admitted, “but, I don’t know any farther Use of the Plants.”

The cactus thus proved a persistent 18th-century rule: The value of any element in nature was measurable in terms of its potential for commodification for pleasure or profit—and pleasure was a commodity reserved for the rich and powerful. Only a few species of cactus offered any benefit to the health or welfare of humans, and those grew only in tropical climes.

By 1812 the growth of gardening in England, and especially the increase in popularity of cacti as exotics, led to the publication of Synopsis Plantarum Succulentarum, . . . Observationibus Anglicanis Culturaque, (Catalogue of Succulent Plants . . . Cultivated in England), by Adrian Hardy Haworth (1767-1833). It contained descriptions of ten species of Opuntia, including O. ferox (fierce), O. fragilis (fragile), and O. polyacantha (many-spined) with the dates of their introduction into Great Britain. However, since cacti had little or no medical, agricultural, or even aesthetic appeal in the Colonies and subsequent states, few American naturalists were interested in it. The nomenclature was hardly current yet. Noah Webster, in his first dictionary, published in 1806, chose not to include “cactus,” nor “opuntia,” nor even “prickly-pear.” He listed “cochineal,” defining it as “a fly or insect used to dye scarlet.,” and “cochenile” as “a blood red color,” but stopped short of introducing the parasitic insect’s favorite host.[7]A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, 1806, facsimile reprint (New York: Crown Publishers, 1970).

A few plant collectors and hunters were active in the U.S. before 1800. Collectors were naturalists who sent specimens to botanists in Europe for taxonomic studies. John Clayton (1694-1773), for example, was a plant collector in Colonial Virginia who sent many native American specimens to the Dutch botanist Jan Frederik Gronovius (1690–1762), who loaned them to Carl Linnaeus, who included them in his various publications. Gronovius himself published a list of Clayton’s specimens in 1743 as Flora Virginica. It included three species of cactus classified not with Linnaean binomials but with descriptive phrases in botanical Latin. One may have been the species that was to become the plains prickly pear (Opuntia polyacantha Haw.; Figures 6, 7); another was O. ficus-indica (Figure 3), an import from the Caribbean and Mexico; a third was Clayton’s eastern prickly pear (O. humifusa (Raf.) Raf.; Figures 3, 4).

John Lyon (d. 1814) was a nurseryman and commercial plant hunter in the central and south Atlantic states, with Philadelphia as his center of operations. The journal and field notes that he kept from 1799 to 1814 remain the sole record of that aspect of American commerce in the Federal era. They contain no references to Cactaceae, so it may be assumed that he never received orders for any species. One of Lyon’s customers was the English nurseryman and plant hunter John Fraser (1750–1811), who made seven trips to the US.[8]Joseph Ewan and Nesta Ewan, “John Lyon, Nurseryman and Plant Hunter, and His Journal, 1799–1814,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol. 53, No. 2 (1963), … Continue reading

Nature’s Prickly Paradox

Although Meriwether Lewis had nothing good to say about either the mosquito or the eye-gnat, he cheerfully recognized one of nature’s supreme paradoxes: the delicate flower that is all the more pleasing to behold because of its incongruous berth amid the defensive armament of a cactus. For Lewis it was a symbolic juxtaposition of pleasure and pain, of delight and repulsion. “The prickly pear is now in full blume,” he wrote on a mild early-summer day in 1805, “and forms one of the beauties as well as the greatest pests of the plains.”[9]In the early 1840s Father Nicholas Point (1799–1868), a Jesuit missionary who spent six years among the Salish, Nez Perce, and Blackfeet Indians. A gifted water-colorist, he viewed the wilderness … Continue reading

Otherwise, the nearly three dozen journal references to prickly pear consist mainly of complaints, now and then providing some insights into the measure of the plant’s pest-factor. Lewis, while making his first reconnaissance up Maria’s River on 4 June 1805, found the prickly pears “so numerous that it required one half of the traveler’s attention to avoid them.” Above the big Gates of the Mountains on 18 July 1805, Sgt. Ordway observed that “the prickley pears are So thick we scarsely could find room to camp without being on them.” While proceeding overland west of the Missouri in a premature hope of meeting some Shoshone Indians, Clark complained that besides the “musqutors” being “verry troublsom,” his feet were “constantly Stuck full Prickley pear thorns” despite having double-soled his moccasins. That night by the light of his campfire he pulled out 17 of those “bryers.” which prompted Lewis to try another expedient: “I have guarded or reather fortifyed my feet against them by soaling my mockersons with the hide of the buffaloe in parchment.”[10]Lewis’s “parchment” undoubtedly refers to a carefully dried buffalo skin, with the hair removed, such as Indian people used as surfaces on which dried roots could be pounded into … Continue reading

But on only three occasions did either he or Clark write anything substantive about any species of Cactaceae.

The Silent Menace

The first of the expedition’s journalists to encounter the prickly pear problem, Clark got the story off to a stressful start. On 19 September 1804 he reported that as the party neared the Big Bend of the Missouri they passed a creek about ten yards wide that flowed through “a plain in which great quantities of the Prickley Pear grows.” Consistent with his policy of occasionally naming places after memorable experiences or observations, he named this one “Prickley Pear Creek.”[11]Now possibly Counselor Creek (or in that vicinity), 30 miles up the Missouri River on Lake Sharpe, which is the long reservoir impounded by Fort Randall Dam. The pain started on the following day, when he explored the portage across the neck of the Big Bend, ascertaining that it was “quit Short 2000 yards only,” but the prairie and hillsides contained “great quantities of the Prickly Pair which nearly ruind my feet.”

Clark also had the last word on the subject. On 1 September 1806, as the Corps passed through the vicinity of the mouth of the “Quicurre or rapid” (Niobrara) river some 855 miles above the Mississippi by today’s measurements, he once more exerted his ability to extrapolate geographic generalities from the sum of his experiences and observations. The plains were “much richer below the Queiquer river than above,” he wrote.[12]Clark’s observation regarding cacti is in Moulton, Journals, 8:416. Indeed, botanical, biological, ecological, and even geological research since the second half of the 20th century have … Continue reading Then, as if to confirm that, he declared that prickly pears were “not common” below that point.

Lewis’s Observations

Near the Corps’ last campsite in the “Little Gate of the Mountain” at the mouth of “Howard‘s Creek,” on 16 July 1805, Lewis made his first effort to describe a species of heavily-armed cactus that conspicuously differed from the plains prickly pear. This new thorny pest was, he observed,

of a globular form,[13]Figure 8, Pediocactus simpsonii, or any of several other similar genera. Elliott Coues, the editor of the 1893 edition of Nicholas Biddle‘s 1814 version, thought it could have been Mamilaria … Continue reading composed of an assemblage of little conic leaves springing from a common root to which their small points are attached as a common center and the base of the cone forms the apex of the leaf which is garnished with a circular range of sharp thorns quite as stif and more keen than the more common species with the flat leaf, like the Cockeneal plant,[14]It has been supposed (Moulton, Journals, 4:433n) that by “Cockeneal plant” Lewis was referring to Nopalea cochenillifera (Linnaeus) Salm-Dyck, Cact. Hort. Dyck, 1849 (since renamed … Continue reading

Two days later, on 18 July 1805, Clark left Lewis in command of the canoes and, accompanied by York, Joe Field and John Potts, set out afoot along the north bank of of the Missouri, in the hope of soon meeting some Shoshones. The going was rough on account of the sharp rocks “which cut and bruised their feet excessively.” Lewis recounted more details of Clark’s experience, and took steps to prepare himself for the same challenge.

nor wer the prickly pear of the leveler part of the rout much less painfull; they have now become so abundant in the open uplands that it is impossible to avoid them and their thorns are so keen and stif that they pearce a double thickness of dressed deers skin with ease. Capt. C. informed me that he extracted 17 of these bryers from his feet this evening after he encamped by the light of the fire. I have . . . fortifyed my feet against them by soaling my mockersons with the hide of the buffaloe in parchment.[15]Lewis undoubtedly refers to a carefully dried buffalo skin, with the hair removed, such as Indian people used for many purposes—as storage containers and suitcases, as well as surfaces on which … Continue reading

His remark about their being “so keen and stif” might indicate that the culprits were the ones “of a globular form.”

Eighteen days later Lewis crossed the “dividing ridge” of the Bitteroot Mountains at the place now called Lemhi Pass, and descended into the valley of the Lemhi and Salmon Rivers. The soil, he noted, was so poor that it produced little else but prickly pear and a “bearded grass” about three inches high. The prickly pear thereabouts, he continued, were of three species:

that with a broad leaf common to the missouri [Figures 6, 7]; that of a globular form [Figures 8, 9] also common to the upper pa[r]t of the Missouri and more especially after it enters the Rocky Mountains[;] also a 3rd peculiar to this country [Figures 10–16]. it consists of small circular thick leaves with a much greater number of thorns. these thorns are stronger and appear to be barbed. the leaves grow from the margins of each other as in the broad leafed pear of the missouri, but are so slightly attatched that when the thorn touches your mockerson it adhears and brings with it the leaf covered in every direction with many others. this is much the most troublesome plant of the three.

Clark was still behind Lewis on that day, but three days after crossing the Bitterroot Divide via the Lost Trail divide into the headwaters of the Bitterroot (Clark’s) River, and one day before reaching the gathering point they would call Travelers’ Rest, he—or the hunters—made a retrospective note on the third new species that Lewis had described (Figure 4):

on the head of Clarks River I observe great quantities of a peculiar Sort of Prickly peare grow in Clusters ovel & about the Size of a Pigions egge with Strong Thorns which is So birded [bearded, i.e., barbed] as to draw the Pear from the Cluster after penetrating our feet.

On the lower Clearwater and Snake (Lewis’s) Rivers in early October of 1805, the rocky riverbeds made worse by low late-season water levels, monopolized all hands’ attention from dawn to dark, but on 16 October 1805, as they approached the Columbia, Clark wrote, cryptically, as it seems: “Great quantities of a kind of prickley pares, much worst than any I have before Seen of a tapering form and attach themselves by bunches.” Elliott Coues, in his 1893 annotated edition of Biddle’s 1814 edition of the journals, cited Charles Vancouver Piper (1888-1926), a botanist and entomologist at the Washington State Agriculltural and Experiment Station at Pullman, who asserted that Opuntia polyacantha Haw (Figure 3). was the only cactus to be found in that vicinity. But although that species’ spines are barbed, the stem segments do not detach easily, and so would not “attach themselves by bunches.” However, Opuntia fragilis (Nutt.) Haw. also grows on the south side of the Columbia and Snake Rivers at least as far west as the Deschutes River.[16]Reuben Gold Thwaites, Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804–1806, 8 vols. (1905; reprint, Scituate, Massachusetts: Digital Scanning, Inc., n.d.), 3:120n. Biddle omitted Clark’s discovery from his 1814 edition of the journals, so Elliott Coues had no opportunity to speculate on the species. Opuntia polyacantha stem segments do not easily detatch from one another, so most likely it was a variety of Opuntia fragilis, the shapes of which may vary from “subspheric to subcylindric, to flattened and elliptic obovate.”[17]Flora of North America, 4:146.

Subsequent journal references to cacti were few. In mid-July of 1806, both Lewis on the Marias and Clark on the Yellowstone remarked that the many pricklypears each saw were flowering, but on the 28th Lewis noted that “the prickly pear has now cast it’s blume.” Lewis had Miller’s Illustration of the Termini Botanici of Linnaeus at hand, and must have spent a few hours of snowbound confinement at Fort Mandan studying the Linnæan Classes and Orders, and learning to write detailed studies of flowers using basic botanical Latin. He proved himself, for example, with his description of the chokecherry on 15 May 1805, including details of its habitat, its season if fructification, as well as its ethnobotany and importance to wildlife. So why, given that he seemed to realize the species he saw were new, didn’t he apply the same care and discipline to his descriptions of the cacti? Why didn’t he ask the Mandans what they thought of those prickly plants? Sometimes it may simply have been inconvenient, or because there were more pressing exigencies. But more than likely his neglect was a consequence of his primary obligation to record useful information, and prickly pears were about as useful as mosquitoes or eye-gnats. Nevertheless, even Lewis’s faltering attempts to find the spiny species worth accounting for placed him at the forefront of the science in North America in that decade.

Cactaceae at the Birth of U.S. Botany

Joseph Ewan traced the history of botany in the United States from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-twentieth century through eight successive epochs. Until 1790s it was chiefly limited to (or by) the energetic efforts of a few foreign naturalists who scoured the land to find native plants—especially trees and medicinal herbs, plus a few ornamentals and exotics—that would be welcome in European markets.[18]“Early History,” in Joseph Ewan, ed., A Short History of Botany in the United States (New York: Hafner, 1969), 27–48. What Ewan termed the Bartram Epoch began in the 1730s and 40s with the work of farmer John Bartram’s circle of friends, whose efforts were mainly directed toward the exportation of plants and seeds from North America to renew declining botanical resources, and to meet the market for exotic plants in British and Continental European countries. This period is notable for the arrival of Carl Linnaeus’s Finn protege, Peter Kalm (1716–1779), who disembarked at Philadelphia in 1748, and whose Travels in North America was published in 1771. Domestically, the apogee of this epoch was reached with the publication of Travels through North & South Carolina, by William Bartram (John’s son, 1739–1823), in 1791, which included references to several species of cactus he saw in that region: Cactus opuntia, Cactus melo-cactus (Fig. 3), Cactus grandiflora, and Cactus cochinelllifer.

Fourth was the Barton Epoch, which began in 1797, when Benjamin Smith Barton was elected Professor of Materia Medica and natural history at the University of Pennsylvania. With the publication in 1803 of his introductory college textbook, The Elements of Botany, he was soon acknowledged as the progenitor of that science in America. For our present purposes, it is worth noting that Barton’s only reference to cacti occurred in the course of his discussion of Linnaeus’s class Icosandria.[19]From Greek eikosi, twenty; andra, male, together meaning twenty (or more) stamens. Linnaeus had placed Cactus as a genus in the class Icosandria and the order Monogynia (one pistil, or female … Continue reading “The genus Cactus,” Barton wrote, “which stands at the head of the class, does not seem to have much relation with the other genera.” That was about all he had to say, except that many species of the genus—of course, he couldn’t say how many—were indigenous to the United States, and that “the fruits of some species of Cactus, or Indian-Fig, are deemed good eating.”[20]Benjamin Smith Barton, Elements of Botany; or Outlines of the Natural History of Vegetables (Philadelphia: Printed for the Author, 1803), 56-59. Web: Google Books, 12 March 2010. Probably it was Barton who recommended Miller’s Illustration of the Sexual System of Linnaeus to Lewis, which, although it contained no analytical information about cacti, was helpful to him in describing other plants.

Botanists who had been disappointed by Lewis’s failure to produce his promised volume on the natural history along the upper Missouri and lower Columbia rivers[21]Jackson, Letters, 2:395-96. nonetheless pored over Biddle’s 1814 paraphrase of the journals for any pertinent information on their subject. Samuel Rafinesque, in an 1817 retrospective account of the growth of the natural sciences in the U.S. since 1800, asserted that among books of the first rank, such as Henry Muhlenberg’s Catalogue of the Hitherto Known Native and Naturalized Plants of North America, and Stephen Elliott’s Sketch of the Botany of South-Carolina and Georgia (both then in progress), he included “Lewis’s and Clarke’s travels on the Missouri and to the North-West Coast of America, which are replete with new facts and discoveries.”[22]Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz (1783-1840), “Survey of the progress and actual state of Natural Sciences in the United States of America, from the beginning of this century to the … Continue reading

A major landmark of the Barton Epoch was the work of Dr. David Hosack, who in 1801 established the Elgin Botanic Garden on the land that is now occupied by Rockefeller Center. Hosack’s garden included 12 species of the genus Cactus, all of which had been listed by Linnaeus.[23]C. coccinellifer, “Cochineal Indian fig”; C. ficus-indica, “White spined Indian fig,” which Lewis might have seen there, although there is no record of such a visit; C. … Continue reading

Thomas Nuttall

The first botanist to focus attention on North American cacti was Thomas Nuttall (1786–1859), an Englishman who lived and worked in the United States from 1808 until 1841. He and Amos Eaton (1776–1842) were instrumental, by their respective means, in popularizing the science in America at all levels.[24]Eaton’s Manual of Botany for the Northern States (i.e., norh of Virginia), the first comprehensive flora of the region, appeared in 1817 and went through eight editions by 1836. Eaton retained … Continue reading In 1811, Nuttall ventured up the Missouri as far as the Mandan villages, where he collected specimens of the only four cacti native to that vicinity: Opuntia polyacantha, O. fragilis, Coryphantha vivipara, and C. missouriensis. In 1818, Nuttall published The Genera of North American Plants, a comprehensive inventory of botanical discoveries in America, which launched a new and fruitful phase of the science at the professional level.

Unlike Frederick Pursh‘s Flora Americæ Septentrionalis (Plants of North America), to which Nuttall conceived his Genera as an addendum—with Pursh’s use of Linnæan Classes and Orders retained—all of his descriptions and observations were written in English, and most were based on close personal observations in the field as well as on information acquired from Indians and EuroAmerican hunters. He never reached the Rockies himself, but he remarked on the habitat occupied by Cactus mamillaris (now Coryphantha missouriensis (Sweet, Britton & Rose. Nipple cactus.) that it grew “on the high hills of the Missouri probably to the mountains.” Of the Cactus viviparus (now Escobaria vivipara) he learned that “in spite of its armature the wild antelope of the plains finds means to render it subservient to its wants by cutting it up with his hooves.” Of the Opuntia fragilis he wrote: “From the Mandans to the mountains . . . and remarkable for its brittleness, the articulations though not very tumid coming off and attaching themselves to every thing which they happen to touch, so much so as to lead the hunters to say that it grows without roots.”[25]Thomas Nuttall, The Genera of North American Plants, 2 vols., 1818. Facsimile edition (New York: Hafner, 1971), 2:295–97. Already Nuttall was able to summarize the genus Opuntia as “an … Continue reading

Complaints

Complaint 1: Eastern Prickly Pear

Figure 5

Eastern Prickly Pear

Opuntia humifusa (Raf.) Raf.

© J.S. Peterson @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database.

Figure 6

Winter Repose

© Ted Bodner @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Miller, J.H. and K.F. Miller, 2005. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife users. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

This was the only species of the plant family Cactaceae that grew wild along the Atlantic Coast from southeastern Massachussets to Florida, and westward as far as the Mississippi River.[26]See the current distribution maps for Opuntia humifusa (Raf.) Raf. in the USDA PLANTS Database, at http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=OPHU. It may have been found on or near Meriwether Lewis’s plantation, Locust Hill, in Albemarle County, Virginia. Carl Linnaeus had named it Cactus opuntia in his Species Plantarum of 1753, but Lewis knew it only as “prickly pear.” Before he left the east coast for his journey down the Ohio, he might well have read about a few species of cactus in the periodical press, or may even have seen a few imported specimens in one of the few plant collectors’ private gardens.

The significance of the word “prickly” gained an additional measure when Lewis encountered the several western species of Opuntia that were to command the Expedition’s attention (Figure 7, Figure 8) and patience. The word “pear” describes one of the most common among the various outlines of the genus’s flat green pads—the rest being circular, lanceolate (lance-shaped), elliptic, or obovate (egg-like). All of them resemble leaves, so we can forgive Lewis for calling them that, but they are really stems that have evolved to function as leaves—photosynthesizing sunlight and storing moisture to sustain the plant through long dry seasons. Cactus stems are called cladodes or phylloclades.[27]Cladode or cladodium is Greek for “many shoots”; phylloclade, also a Greek word, denotes “leaf-like.” OED Online. (Accessed 18 March 2010.)

The dark bumps on the specimen pictured here, some of which have pale centers, are nodes called areoles. (The light-green spots in this photograph are droplets of water from the irrigation system in the USDA Agricultural Research Service’s National Arboretum.) In most cacti, one or more long, stiff spines grow from the center of each areole. Those spines are vestigial leaves, but they lack the leaf-cell genes common to most true leaves. (Compare with Figure 4.) Typically, only a few of the areoles on each cladode of an O. humifusa produce spines, while the rest are spineless—glabrous, or “bald.”

The areoles also hold clusters of short (up to 4 mm), pale-yellow to dark-brown, barbed spines called glochids.[28]Britton and Rose, (1912-18), 1:127. The glochids are so fine that they can hardly be seen, but when embedded in a person’s skin they can produce noticeable irritations, and are extremely difficult to extract. Modern cactus gardeners have recourse to the 20th-century expedient of applying any sort of adhesive to pull them out. The areoles on O. humifusa are farther apart than those of the plains prickly pear, O. polyacantha (Figure 3), and may hold only one or two 5 cm (2 in.) spines each, although many lack spines altogether.

Using Lyon’s specimen of the eastern prickly pear as the basis for his taxon, and choosing Cactus as the generic name, Linnaeus had classified it in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturæ as “Cactus opuntia.” It was renamed Cactus humifusus in 1820 by Constantine Rafinesque (1783-1840), who published it with his description of a type specimen. He revised his narrative in 1830, and reclassified the species as Opuntia humifurus. The specific epithet has since been changed to the form humifusa.

Until recently it was generally held that the generic term came from the Latin “Opuntius,” in turn from the Greek city of Opus, but that is now questionable. Instead, it may have come from the Greek opos, “fig juice,” evoking the shape and flavor of the plant’s fig-like fruits.[29]Urs Eggli and Leonard E. Newton, Etymological Dictionary of Succulent Plant Names (New York: Springer-Verlag, 2004), 172. A third but etymologically more remote possibility is that it was derived from a combination of the Aztec noun nopali (fruit) and the Latin pungere (to prick or sting).

Like a few other species of Opuntia, O. humifusa has evolved a strategy to withstand the cold winters of the temperate latitudes, which is implied by its specific epithet, humifusa meaning “spread out on the ground.” In autumn it becomes procumbent, which means “prostrate or trailing on the ground, but not taking root.”[30]Linnæ-Turton, General System, vol. 7, “Explanation of Terms.” The stems lose their moisture, become limp and spongy, and flatten out on the ground to gain a little warmth from the earth and allow blankets of snow to insulate them from winter winds. The pale purple appendages on the upper cladode are nearly-ripe edible fruits that matured in the previous growing season.

Complaint 2: Plains Prickly Pear

Figure 7

Plains Prickly Pear

Opuntia polyacantha Haw.

© 2003 Wayne Phillips.

Figure 8

“the more common species with the flat leaf”

© J. Agee 2001.

Lewis would have been dumfounded by the contrast between the relatively non-threatening eastern species of prickly pear, and the heavily-armed plains prickly pear. The botanical terms arms and armed denote the spines and thorns of certain plants, which in this instance are defensive arms that nature has evolved to discourage rodents and other mammals from eating those moist, succulent pads.

There are more than 120 genera and 1200 species in the cactus family, all native to North and South America. Among the most numerous species of the genus Opuntia are the plains prickly pears, identifiable by their spiny stems that in summer trail erect along the ground, plus its own seasonal flower, and fruits the size, shape, and almost the color of figs. Lewis referred to this species on 13 August 1805 as “the broad leafed pear of the Missouri.” Of the seven species of cacti that are native to the Rockies and the High Plains, Lewis preserved specimens of two, including one evidently of O. polyacantha, but both have long since been lost.

The specific epithet polyacantha means “many thorns” in botanical Latin. Plains pricklypear was first described for science in 1819 by the English gardener Adrian Haworth (1767-1833), a devoted student of succulent plants.

With or without spines as numerous as those of O. polyacantha, the drying and pressing of suculent cactus specimens of many dimensions for botanical study is considerably more challenging than with most other plants, a factor which measurably protracted the development of cactus taxonomies. Analytical work normally carried out in the laboratory or “cabinet” using collected specimens had to be completed in the field.

Each little clump of cottony, waxy fluff on these prickly pear stems is a cocoon that shelters a single wingless female scale insect called a cochineal (kah-chin-eel). The cocoon serves to protect her eggs from hot sun and chilling rain.

Complaint 3: Mountain Cactus

Figure 9

Mountain Cactus

Pediocactus simpsonii (Engelm.) Britton & Rose

© Sheri Hagwood @ USDA-PLANTS Database.

The small size and scattered occurrences of this species, easily hidden among low grasses and shrubs on the prairie—pedio is Latin for “a plain”—must have made it especially annoying to the Corps’ hunters. Its plants usually grow singly; rarely do two or three spring from the same root. Hunting on the move in cactus country demanded acute attention to many environmental details at once.

This was one of the first cacti carried to Europe by explorers of the West Indies, and for some years it was the only species known to Carl Linnaeus, who assigned it the name Cactus mammillaris in his Species Plantarum of 1753. It had already been described by the Dutch botanist Jan Commelin in 1697 and the German botanist Paul Hermann in 1698. In 1819 Adrian Haworth renamed it Mammillaria conica. His description, “Tubercles large, conic,”[31]N. L. Britton and J. M. Rose, The Cactaceae, 4 vols. in 2 (reprint of second edition, 1937; New York: Dover, 1963), 4:70. resembled Lewis’s. In 1913 Britton and Rose traced its taxonomy from the 1863 description by the German-American botanist George Engelmann (1809-1884), who had named the species simpsonii, for botanist Charles Torrey Simpson (1846-1932).

As described in Flora of North America, ball cactus can be up to 15 cm (5.9 in.) broad by 15cm high; the surface of the stem is covered with grooved pyramidal protuberances called tubercles, each framed radially by 15 to 20 spines from 5 to 21 cm. (1.9 to 8.2 in.) long.[32]Kenneth D. Hell & J. Mark Porter. 2004. Pediocactus simpsonii. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993–. Flora of North America North of Mexico, 15 vols. (New York: Oxford … Continue reading

Complaint 4: Missouri Foxtail Cactus

Figure 10

Missouri foxtail cactus

Escobaria missouriensis (Sweet) D.R. Hunt

© 2003 Joseph A. Marcus, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, University of Texas, Austin.

Sometimes called pincushion cactus or nipple cactus, Escobaria missouriensis (Sweet) D. R. Hunt is another possible identity for Lewis’s cactus “of a globular form.” It is still found from the Mississippi to the Rockies. Robert Sweet (1783-1835), the author of the original description (1826) under the name Mammillaria missouriensis, was a prominent English botanist and gardener. D. R. Hunt (b. 1938) is the English specialist in Cactacae who changed the generic name from Mammillaria to Escobaria, the latter memorializing the Escobar brothers of northern Mexico. This species ranges in size from 2 to 8 cm (.078 – 3.1 in.) in height, either singly, or in clumps of more than 30 cm (11.8 in.) in diameter.[33]Flora of North America, 4:222-228.

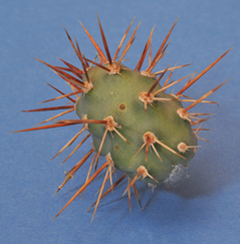

Complaint 5: Brittle Prickly Pear

Figure 11

Brittle Prickly Pear

Opuntia fragilis Haw.

© Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation.

Figure 12

“Pin-Pillow” Cactus

© Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation.

The longer and darker spines on this cladode are entirely dead; the shorter, lighter ones are younger, having live cells only at their bases. The cladode pictured here is 24 mm (0.9 in.) long by 15 mm (0.6 in.) in diameter. The 3-8 spines per areole spines are up to 24 mm (.9 in.) in length.

Sometimes called the “Little Prickly Pear,” the specific epithet in its official name Opuntia fragilis Haw. reflects its most obvious characteristic, the fragile connections between its cladodes, which enables the uppermost member to propagate itself by clinging to a passing carrier with its barbed spines (Figure 7-8), to be deposited in a new, often distant location where it can take root. Given that asexual mode of reproduction it is no wonder that O. fragilis is seldom seen in bloom.

In terms of the average size of its stems, Opuntia fragilis is the smallest species of cactus in North America, and the one most capable of surviving cold temperatures. Its distribution extends from southern Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, westward into Oregon and Washington, and northward to upper British Columbia and southern Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.[34]Flora of North America, 4:93, 124, 146. Eric Ribbens, “Opuntia fragilis: Taxonomy, Distribution, and Ecology,” Haseltonia, Yearbook of the Cactus and Succulent Society of America, Number … Continue reading

Adrian Haworth related that the botanist Philip Miller (1691-1771) had declared, “it is called Pin-Pillow in the west Indies, from the appearance which the plump branches have to a pincushion stuck full of pins”—inserted upside down, of course.[35]Haworth, Synopsis Plantarum, p. 187.

Adrian Haworth, the British botanist who earned a reputation as the pioneer expert on cacti, wrote the first description of the species, which had been introduced from the West Indies in 1690 into a collector’s garden in the vicinity of London. Haworth named it Opuntia curassavica, deriving the specific epithet from Curaçao, the island in the Netherlands Antilles where it had first been found. “This is a very shy-flowering plant,” he wrote, and has only once attempted to blossom with me.” Indeed, the latest account of it notes, “in many places, it flowers infrequently, if at all.”[36]Flora of North America, http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1 &taxon_id=242415221. Britton and Rose, The Cactacae, 1:193. Its branches were so extremely brittle that they break off at the joints on the slightest touch, adhering to the flesh or clothes of any person coming in contact with them; and create much pain and trouble to disengage, as their long sharp prickles are thickly and reversely barbed with invisible points.”

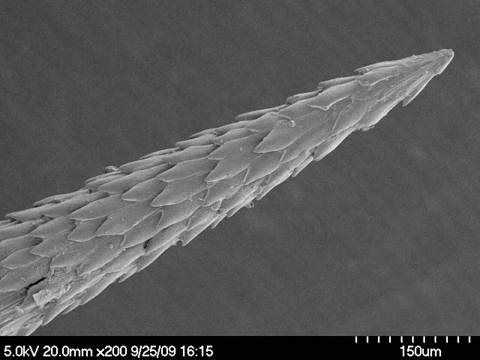

Under the Microscope

An electron microscopy image of the tip of a spine of Opuntia fragilis shows its reversed barbs at a magnitude of 200 times their actual size.[37]The following EM images have been provided by Jim Driver of the Electron Microscopy Facility, Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula. The EM Facility is supported in part by … Continue reading No one, including Lewis, could have realized the magnitude of those microscopic barbs.

An electron microscope image here compares one of the spines (bottom) that is attached to the cladode shown in Figure 11, with the tip of an ordinary sewing needle. The tip of the spine has been damaged—a few barbs are missing—but is still considerably sharper than the sewing needle. The barbs to the left of the damaged tip cannot easily be felt with fingers calloused by the kinds of work the Corps and its captains carried out daiy. It is only upon pulling them out of one’s flesh that the tenacity of the barbs is sensed.

This is the irritating end of a glochid (with a broken tip) that is one of a cluster of short (3- to 4-mm), yellowish, flexible and retrorsely barbed spinules that radiate from the upper margin of each areole on the stem of an Opuntia fragilis. The glochid in this EM image, shown at 800 times its actual size, is from one of the 20 areoles on the cladode pictured in Figure 11, each holding from 5 to 7 glochids that are 37.5 um (micrometers) in diameter—about half the thickness of a fine human hair.

Glochids are easily detachable from areoles by the slightest contact with human skin, but they are extremely difficult to extract. Being firmly embedded in the epidermis, they become a sub-visible, burning irritant fully as irritating as a mosquito bite, which is refreshed with each contact with some other surface.[38]Stanley L. Welsh, “Utah flora: Cactacae,” The Great Basin Naturalist, Vol. 44, No. 1 (31 January 1984), 69. Modern cactus-growers keep a roll of adhesive-coated tape handy for relief.

Areoles and the glochids that grow from them are the vestiges of branches and leaves that evolved on desert plants to reduce water loss and enable them to survive in extremely dry habitats.

“The greatest pests” in Perspective

Clay Jenkinson, a former director and editor of Discovering Lewis & Clark, kneels (carefully!) beside four mats of Opuntia fragilis Haw. Typically, mats are more thoroughly camouflaged than these are by grasses and other low plants, which accounts for Lewis’s remark—on 4 June 1805, during his first exploration of Maria’s River—that these cacti “are so numerous that it require[s] one half of the traveler’s attention to avoid them.” Imagine the frustrations of the hunters, whose primary job was to keep watching for game. Moreover, it is pointless to try to walk a straight line through areas where such plants grow.

With several spines of this cladode firmly embeded in the tough, thick leather of a modern boot, one can appreciate Clark’s plaint of 8 September 1805, the day prior to their arrival at the creek the captains named “Travellers-rest”:

On this part of the river on the head of Clarks River I observe great quantities of a peculiar Sort of Prickly peare grow in Clusters ovel & about the Size of a Pigions egge with Strong Thorns which is So birded [bearded] as to draw the Pear from the Cluster after penetrateing our feet.”

Homesteaders in the west, who were required to improve their claims within a given period after filing, could do so in part by clearing their land of cactus. The most efficient way to do that was to burn it early in the spring, before the rains came and grasses greened-up. It could require several seasons of burning before all his land could be plowed.

Notes

| ↑1 | Charles Willson Peale mentioned Turton’s translation in a letter to Jefferson dated 3 November 1805. Jefferson included it in a list of books he recommended to his friend George Wythe. Jefferson Papers, Retirement, vol. 1, p. 581. For more on Linnaeus’s system see Bighorn Sheep. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Thomas Hariot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (London, 1588). Metaquesunnauk was an Algonquian word for the fruit of several prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) Hariot also carried back additional specimens of “medicinal” tobacco (Nicotiana spp.) as gifts to European royalty. For nearly 400 years thereafter, even the best educated persons worldwide would be blissfully unaware that Nicotiana vulgaris was far more deadly than any cactus. |

| ↑3 | See the full text of Menzies’ journal of Vancouver’s voyage, April to October 1792, at https://archive.org/stream/menziesjournalof1792menz/menziesjournalof1792menz_djvu.txt. |

| ↑4 | Donald Jackson, “Some books carried by Lewis and Clark,” Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, 16 (Oct. 1959), 3–13. |

| ↑5 | The specific epithet ficus-indica means “fig of the [West] India.” The initial L. stands for Linnaeus, who published the first taxon of it; Mill. stands for Philip Miller (1691–1771), the Scottish botanist and gardener who revised Linnaeus’s taxon for this species. |

| ↑6 | Philip Miller, The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit and Flower Garden, as also the Physick Garden, Wilderness, Conservatory, and Vineyard, (London; first (Folio) edition, 1733; seven more in the author’s lifetime plus many more, including spinoffs. A kitchen garden was devoted to the growing of table foods; a “physick” garden contained medicinal herbs; a “wilderness” garden consisted of wild plants arranged in an idealized naturalistic setting; a “conservatory” was a hothouse or greenhouse in which temperature and humidity were more or less elevated and controlled to permit the cultivation of certain tropical species. |

| ↑7 | A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, 1806, facsimile reprint (New York: Crown Publishers, 1970). |

| ↑8 | Joseph Ewan and Nesta Ewan, “John Lyon, Nurseryman and Plant Hunter, and His Journal, 1799–1814,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol. 53, No. 2 (1963), 1–69. American trees were more in demand in Britain than American cacti. |

| ↑9 | In the early 1840s Father Nicholas Point (1799–1868), a Jesuit missionary who spent six years among the Salish, Nez Perce, and Blackfeet Indians. A gifted water-colorist, he viewed the wilderness with an artist’s eye. Writing of the “pricleper” (prickly pear?) he wrote: “The prettiest of [the prairie flowers] is the Cactus Americana. . . . I never saw anything as pure and vivid as the bloom of this charming flower. . . . [which], surrounded by a great many thorns, is only two inches from the earth and grows naturally only in the desert. Thus it, more than the rose, could be the symbol of the pleasures of this world.” Michael P. Branch, Reading the Roots: American Nature Writing Before Walden (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 204), 315. Fr. Point’s poetic conclusion strikingly resonates with Lewis’s acknowledgment of nature’s prickly paradox. |

| ↑10 | Lewis’s “parchment” undoubtedly refers to a carefully dried buffalo skin, with the hair removed, such as Indian people used as surfaces on which dried roots could be pounded into flour, or sewed into storage containers, parfleches, suitcases and battle shields. The skin would have been soft and flexible enough to be sewn, and tough enough to provide superior protection from cactus spines. |

| ↑11 | Now possibly Counselor Creek (or in that vicinity), 30 miles up the Missouri River on Lake Sharpe, which is the long reservoir impounded by Fort Randall Dam. |

| ↑12 | Clark’s observation regarding cacti is in Moulton, Journals, 8:416. Indeed, botanical, biological, ecological, and even geological research since the second half of the 20th century have established that at least since the end of the Pleistocene ice age, between 12,000 and 10,000 years B.P., the Niobrara River valley has been part of a narrow transitional zone between the central grasslands and the High Plains. Robert B. Kaul, Gai E. Kantak and Steven P. Churchill, “The Niobrara River Valley, a Postglacial Migration Corridor and Refugium of Forest Plants and Animals in the Grasslands of Central North America,” The Botanical Review, Vol. 54, No. 1 (January–March 1988), 45–81. For a simplified overview of the , see the National Park Service’s web page on the Niobrara National Scenic River, at www.nps.gov/niob. |

| ↑13 | Figure 8, Pediocactus simpsonii, or any of several other similar genera. Elliott Coues, the editor of the 1893 edition of Nicholas Biddle‘s 1814 version, thought it could have been Mamilaria missouriensis. |

| ↑14 | It has been supposed (Moulton, Journals, 4:433n) that by “Cockeneal plant” Lewis was referring to Nopalea cochenillifera (Linnaeus) Salm-Dyck, Cact. Hort. Dyck, 1849 (since renamed Opuntia cochenillifera; USDA PLANTS Database), a succulent plant that reaches 4 to 5 feet in height, that had been grown in various tropical countries, especially in Jamaica and southern Mexico in the vicinity of Oaxaca for the cultivation of the cochineal scale, from which a brilliant scarlet dye was manufactured. However, the nopal was rarely seen in the United States, and then only in a few private gardens. Moreover, it was known at that time that cochineals feed on nearly any of the so-called pricklypears, so alternatively Lewis might have had in mind the Opuntia humifusa (Raf.) Raf. (Notice the cochineal cocoons on Opuntia polyacantha in Figure 7, photographed near the Sulfur Spring below the Great Falls of the Missouri.) |

| ↑15 | Lewis undoubtedly refers to a carefully dried buffalo skin, with the hair removed, such as Indian people used for many purposes—as storage containers and suitcases, as well as surfaces on which dried roots could be pounded into powder. It would have been flexible enough to be sewn, and tough enough to provide some protection from cactus spines. |

| ↑16 | Reuben Gold Thwaites, Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804–1806, 8 vols. (1905; reprint, Scituate, Massachusetts: Digital Scanning, Inc., n.d.), 3:120n. |

| ↑17 | Flora of North America, 4:146. |

| ↑18 | “Early History,” in Joseph Ewan, ed., A Short History of Botany in the United States (New York: Hafner, 1969), 27–48. |

| ↑19 | From Greek eikosi, twenty; andra, male, together meaning twenty (or more) stamens. Linnaeus had placed Cactus as a genus in the class Icosandria and the order Monogynia (one pistil, or female reproductive member of a flower). |

| ↑20 | Benjamin Smith Barton, Elements of Botany; or Outlines of the Natural History of Vegetables (Philadelphia: Printed for the Author, 1803), 56-59. Web: Google Books, 12 March 2010. |

| ↑21 | Jackson, Letters, 2:395-96. |

| ↑22 | Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz (1783-1840), “Survey of the progress and actual state of Natural Sciences in the United States of America, from the beginning of this century to the present time,” The American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review, vol. 2, no. 2 (December 1817). Web: American Periodicals Series 0nline, 1740–1900, ProQuest LLC, 16 January 2010. |

| ↑23 | C. coccinellifer, “Cochineal Indian fig”; C. ficus-indica, “White spined Indian fig,” which Lewis might have seen there, although there is no record of such a visit; C. flagelliformis, “creeping Cereus,” whiplash or rattail cactus; C. glomeratus, “smallest Indian fig” or ; C. grandifloris or night flowering Cereus, a widely used medicament; C. mammillaris, “small Melon thistle”; C. melocactus, “great Melon thistle”; C. opuntia, “common Indian fig” (the eastern prickly pear sent to Linnaeus by the Virginian John Clayton, and the only species from North America, the rest being from Mexico, Central, and South America); C. pentagonus, “five sided torch thistle”; C. pereskia, “Barbadoes gooseberry” or rose cactus; C. triangularis, “triangular Cereus”; and C. tuna, “black spined Indian fig.” |

| ↑24 | Eaton’s Manual of Botany for the Northern States (i.e., norh of Virginia), the first comprehensive flora of the region, appeared in 1817 and went through eight editions by 1836. Eaton retained Linnaeus’s binomial nomenclature but adopted the taxonomy of “natural orders” conceived by the French botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748–1836). When it came to cacti, however, Eaton described only the flowers, not the more conspicuous aspects of the stems or “leaves,” and areoles. In the second edition of the Manual, Eaton recommended the study of botany to the attention of ladies, but found it unnecessary to reiterate that in the third (1822) edition since, he observed, “I believe more than half the botanists in New England and New York are ladies.” |

| ↑25 | Thomas Nuttall, The Genera of North American Plants, 2 vols., 1818. Facsimile edition (New York: Hafner, 1971), 2:295–97. Already Nuttall was able to summarize the genus Opuntia as “an American genus of near 40 species, almost exclusively tropical.” Today, according to Flora of North America (vol. 4, page 123), there are approximately 150 species of Opuntia in North and South America, Mexico, and the West Indies. |

| ↑26 | See the current distribution maps for Opuntia humifusa (Raf.) Raf. in the USDA PLANTS Database, at http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=OPHU. |

| ↑27 | Cladode or cladodium is Greek for “many shoots”; phylloclade, also a Greek word, denotes “leaf-like.” OED Online. (Accessed 18 March 2010.) |

| ↑28 | Britton and Rose, (1912-18), 1:127. |

| ↑29 | Urs Eggli and Leonard E. Newton, Etymological Dictionary of Succulent Plant Names (New York: Springer-Verlag, 2004), 172. |

| ↑30 | Linnæ-Turton, General System, vol. 7, “Explanation of Terms.” |

| ↑31 | N. L. Britton and J. M. Rose, The Cactaceae, 4 vols. in 2 (reprint of second edition, 1937; New York: Dover, 1963), 4:70. |

| ↑32 | Kenneth D. Hell & J. Mark Porter. 2004. Pediocactus simpsonii. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993–. Flora of North America North of Mexico, 15 vols. (New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 1993–), 4:214. |

| ↑33 | Flora of North America, 4:222-228. |

| ↑34 | Flora of North America, 4:93, 124, 146. Eric Ribbens, “Opuntia fragilis: Taxonomy, Distribution, and Ecology,” Haseltonia, Yearbook of the Cactus and Succulent Society of America, Number 14 (December 2008), 94-110. |

| ↑35 | Haworth, Synopsis Plantarum, p. 187. |

| ↑36 | Flora of North America, http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1 &taxon_id=242415221. Britton and Rose, The Cactacae, 1:193. |

| ↑37 | The following EM images have been provided by Jim Driver of the Electron Microscopy Facility, Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula. The EM Facility is supported in part by grant #RR-16455-04 from the National Center for Research Resources (Biomedical Research Infrastructure Network program) of the National Institutes of Health. The EM Facility’s website is at http://emtrix.dbs.umt.edu/ |

| ↑38 | Stanley L. Welsh, “Utah flora: Cactacae,” The Great Basin Naturalist, Vol. 44, No. 1 (31 January 1984), 69. |