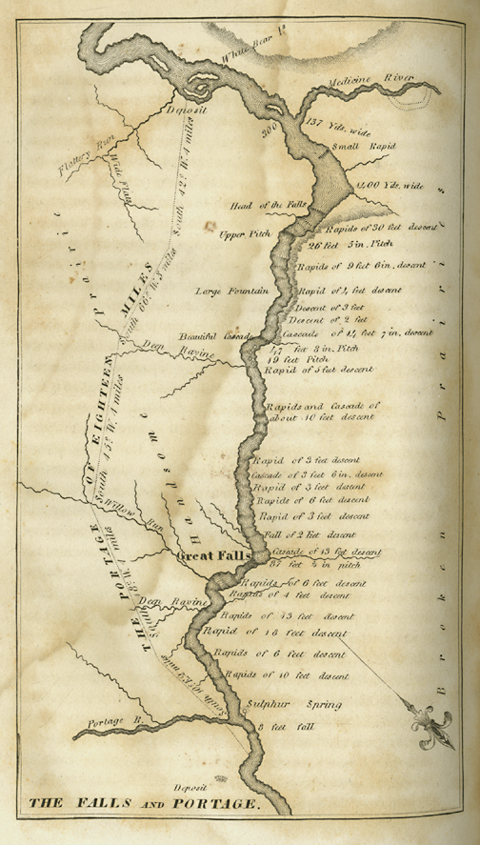

Clark’s Two Surveys

Clark’s portage route survey for the portage around the falls consisted of six courses in 17¾ miles plus 46 poles (759 feet). As a check, or “close,” of his route survey from the lower portage camp to the upper one, Clark apparently repeated it in the opposite direction. It might also have served as a reminder to those who would return to the falls en route home the following summer.

The course from the White Bear Islands above the portage N. 42° E [the opposite of South 42° West] 4 miles leaveing the riveens of flattery run to the right. thence a course to the South Extremity of a ridge North of the South mountains for 8 miles & a half passing three riveens, the 2d is willow run. 11 miles from the Islands. Thence a course to the highest pinical of the North Mountain, leaveing the riveens of Portage or red Creek to the right, & the riveens of the river to the left to the mouth of Portage Creek 4 miles & a half, to the perogue which is on the river North Side & nearly opposit the place we buried Sundery articles is 1 mile down the river,[1]Moulton, 4:316. The supplies cached at the lower portage camp included Lewis’s portable writing desk containing some books, the plant and mineral specimens collected since leaving Fort Mandan, … Continue reading The Swivel we hid under the rocks in a clift near the river a little above our lower camp.

On the twenty-third, Clark “cut of[f] several angles of the rout . . . shortened the portage considerably, measured it and set up stakes throughout as guides to marke the rout.”

Bear Problems

Soon after Clark and his survey crew pitched camp on the southeast riverbank on 18 June 1805, two herds of buffalo crossed the river, one above the camp and one below. With an eye to stocking up on meat so that the portage wouldn’t have to be protracted by a daily need to hunt, and also against an anticipated scarcity of game in the mountains, they killed eight of the big animals.

Unavoidably, the carcasses the hunters left behind also attracted the large neighborhood population of grizzlies, or “white bears,” as they were often called. Alexander Willard, sent for a load of meat only 170 yards away, was chased back into camp by one; another drove John Colter into the river. On the twenty-fifth, Joseph Field had his second narrow escape from a threatening grizzly; he “leaped down a steep bank of the river on a stony bar where he fell cut his hand bruised his knees and bent his gun.” By the 28th Lewis declared, “The White bear have become so troublesome to us that I do not think it prudent to send one man alone on an errand of any kind, particularly where he has to pass through the brush.”

Flattery Creek

Upper Portage Camp

White Bear Islands

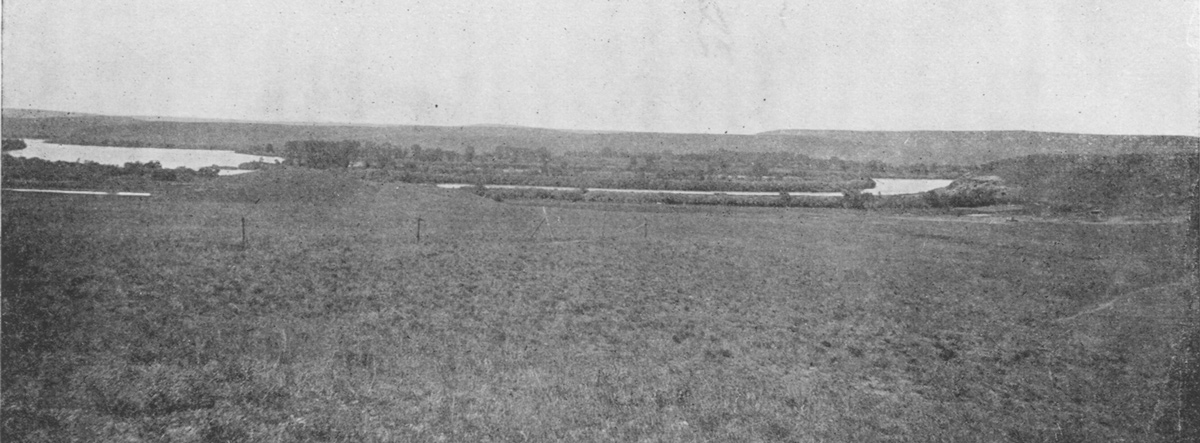

Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”

Wheeler’s caption for the above photo read: “The White Bear Islands and the Missouri above the City of Great Falls. The Lewis and Clark portage from below the Great Falls, followed approximately the line of poles seen at the left centre of the illustration.” The view is toward the southwest (see Clark’s map below). The upper portage camp was somewhere to the left of the islands. Flattery Run was perhaps three-quarters of a mile farther to the left. All three of the islands, no doubt already altered by riverine forces during the 19th century, are in the photo, although indistinctly. They slowly dissolved and merged with the riverbanks during the 20th century. The Sun River (“Medicine River”) is three miles downstream, to the right.

On 19 June 1805 Clark set out to examine a small creek above their upper portage camp, “and found the Creek only Contained back water for 1 mile up.” On his maps, he labeled it “Flattery Run.” In today’s dictionaries the noun flattery is defined as “excessive or insincere praise,” especially in order to win favor,[2]The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (3rd ed., New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1992). and thus it may seem to be a strange name for a stream. In Clark’s day, however, the verb flatter had another meaning, to “deceive, give false hopes,” and the noun flattery borrowed the same connotation from its kin.[3]Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, (1806; reprint, with an introduction by Philip B. Gove, New York: Crown Publishers, 1970). In other words, the “creek” didn’t feed the river; the river backed up into the creek bed.

In 1778 Captain James Cook, the famous British explorer, left a similarly perplexing name on the Northwest Coast of the U.S. In search of the Strait of Juan de Fuca (separating Vancouver Island from the mainland), which had been discovered nearly a century earlier, Cook “doubled” or rounded the point at the north end of today’s Olympic Peninsula and supposed it marked the opening of the long-sought passage. He soon found he was mistaken. “In this very latitude,” he noted in his log book, “geographers have placed the pretended Strait of Juan de Fuca. But nothing of that kind presented itself to our view, nor is it probable that any such thing ever existed.” He had been “flattered,” so he named the point “Cape Flattery.” Since Thomas Jefferson‘s library contained a copy of Cook’s journals,[4]Published in 1784. Donald Jackson, Thomas Jefferson and the Stoney Mountains: Exploring the West from Monticello (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 45-46, 55-56. which its owner may have encouraged Lewis to study with particular reference to the Northwest Coast, it may have been Lewis and not Clark who pinned the name on Flattery Run.

Run v. Creek

In Webster’s concise Dictionary of 1806, run had several definitions: “a course, cadence, reception, success, a skain [skein] of 20 knots, unusual demands upon a bank, the aft part of a ships bottom,” and lastly, “a small stream.” Its use to denote “a small, fast-flowing stream” is still current in the eastern U.S., especially Virginia, West Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, and southern Pennsylvania. In some places a run was “a valley or depression between hills; . . . a channel or ravine cut by water, whether containing water or not.”[5]Dictionary of American Regional English (4 vols. to date, Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985).

A southern synonym is branch, which Lewis and Clark did not use in this sense, while creek (or crick) is still common throughout the north and west. In 1806 Webster defined creek as “a small bay, alley, nook, corner, turn.” The adjective creeky meant “winding.” The oldest spelling–and pronunciation–was crick, or krick. Many people then–obviously excluding Lewis and Clark–used the words creek or crik only in reference to an inlet from the sea.

It is difficult to account for the journalists’ choices among creek, river, and run. The stream near the lower portage camp was called both a creek and a river, never a run. But the largest ravine between it and the upper portage camp was Willow Run, which contained fresh running water; it is now known as Box Elder Creek. In general, they favored creek or river (“large stream”), over run, so the choice of the latter as an appositive to Flattery compounds the irony. Indeed, “Flattery Run” is a much more intriguing phrase than the newer, more literal, but grittier one for the same place: Sand Coulee. A coulee is a deep, slope-sided ravine, usually dry in summer except during heavy rainfalls. The geological fact is, “Flattery Run” is part of the bed the Missouri River occupied here prior to the last Ice Age.[6]David W. Baker, “Great Falls Area Geology Field Trip,” http://www.3rivers.net/~dbaker/gtfalls.htm.

The River Turns Red

After a thunderstorm on 27 June 1805, Lewis remarked that “the water on this [south] side of the river became of a deep crimson,” and further observed that “there is a kind of soft red stone in the bluffs and bottoms of the gullies in this neighbourhood which forms this colouring matter.” The next day he noticed that “portage creek had arisen considerably and the water was of crimson colour and illy tasted.” In fact, Clark labeled that watercourse “Red” river or creek on at least two of his sketch maps.[7]Moulton, Atlas maps 42 and 54.

Portage Creek (or River) has been known as Belt Creek since the late 1800s. Its sources lie nearly ninety miles to the south, on the slopes of two adjacent “island” ranges east of the Rockies, the Highwood Mountains and the Little Belt Mountains. When it reaches the prairie it cuts down through layers of the 120 million-year-old Kootenai Formation picking up clay that contains ferric oxide, which gives the water a rusty brown color. Since the 1940s, at least, agricultural use of the land drained by Belt Creek has somewhat diluted the solution so that the reddish-brown is less noticeable. The creek also passes through glacial till and several shales containing fair mounts sodium, magnesium, bicarbonate and sulphate salts, which together make its water “illy tasted.”

Portage Conditions

After five days of preparation, consumed mainly by the process of surveying and flagging a suitable route, the portage around the falls began on 21 June 1805, and the “Handsome Prairie” became a new experience for every man. “This evening,” wrote Lewis, “the men repaired their mockersons, and put on double souls to protect their feet from the prickley pears.”

There was the infernal wind, which blew in their favor just once that we know of: On 26 June 1805 “the Sales were hois[t]ed in the Canoes as the men were drawing them and the wind was great relief to them being Sufficiently Strong to move the Canoes on the Trucks, this is Saleing on Dry land in every Sence of the word.”[8]Late in the 20th century the average maximum wind velocity in the city of Great Falls during June and July was between 12.8 and 14.5 miles per hour. Peak gusts of 92 mph were recorded in June 1970, … Continue reading Summer thunderstorms drenched the men, soaked the baggage, and “Caused the rout to be So bad wet & Deep thay Could with dificuelty proceed.” The sticky gumbo accumulated on the little wheels of the wagons, requiring the men to stop frequently to scrape it off–a major chore in itself, without sticks to be found on the treeless prairie. (Gumbo can bring a modern heavy-duty, four-wheel-drive farm implement to a halt within a short distance.) Still worse, when the sun came out, the gumbo dried hard and sharp.

“During the late rains,” Lewis explained,

the buffaloe have troden up the praire very much, which having now become dry the sharp points of earth as hard as frozen ground stand up in such abundance that there is no avoiding them. this is particularly severe on the feet of the men who have not only their own wight [weight] to bear in treading on those hacklelike points but have also the addition of the burthen which they draw and which in fact is as much as they can possibly move with. they are obliged to halt and rest frequently for a few minutes, at every halt these poor fellows tumble down and are so much fortiegued that many of them are asleep in an instane; in short their fatiegues are incredible; some are limping from the soreness of their feet, others faint and unable to stand for a few minutes, with heat and fatiegue.

“Yet no one complains,” he concluded with pride. “All go with cheerfullness.”

Fourth of July Celebration

The shuttling of all the baggage and six canoes across the prairie to the upper portage camp opposite White Bear Islands began on 21 June 1805 and was completed on 2 July 1805. All in all, it was one of the most grueling undertakings on the entire expedition, yet on 4 July 1805 Lewis, still confident that his leather-covered, iron-framed boat would fulfill its purpose, faced the future with undaunted courage. “We all beleive that we are now about to enter on the most perilous and difficult part of our voyage, yet I see no one repining; all appear ready to met those difficulties which wait us with resolution and becoming fortitude.” Indeed, that night “the fiddle was plyed and they danced very merrily untill 9 in the evening when a heavy shower of rain put an end to that part of the amusement tho’ they continued their mirth with songs and festive jokes and were extreemly merry untill late at night.” On the fair and pleasant morning of the ninth they launched the “iron or leather Boat.” By late evening they watched it spring its seams and take on water. It was useless. Lewis’s passionately held plan was a failure. On the fifteenth, after carving two more cottonwood dugout canoes to take its place, the expedition was under way once more.

Great Falls Portage is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. There are numerous public access areas along the Missouri River and interpretation with a view on 40th Avenue in Great Falls, MT.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | Moulton, 4:316. The supplies cached at the lower portage camp included Lewis’s portable writing desk containing some books, the plant and mineral specimens collected since leaving Fort Mandan, several kegs of pork and flour, two guns and some ammunition, and a few of the men’s belongings. 4:334. Two “deposits” were dug near the upper portage camp. One held some of Lewis’s papers, medicines, and all the plant specimens he had collected since leaving Fort Mandan. The other contained the hardware of the failed iron-framed boat. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (3rd ed., New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1992). |

| ↑3 | Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, (1806; reprint, with an introduction by Philip B. Gove, New York: Crown Publishers, 1970). |

| ↑4 | Published in 1784. Donald Jackson, Thomas Jefferson and the Stoney Mountains: Exploring the West from Monticello (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 45-46, 55-56. |

| ↑5 | Dictionary of American Regional English (4 vols. to date, Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985). |

| ↑6 | David W. Baker, “Great Falls Area Geology Field Trip,” http://www.3rivers.net/~dbaker/gtfalls.htm. |

| ↑7 | Moulton, Atlas maps 42 and 54. |

| ↑8 | Late in the 20th century the average maximum wind velocity in the city of Great Falls during June and July was between 12.8 and 14.5 miles per hour. Peak gusts of 92 mph were recorded in June 1970, and 85 mph in July 1990. Lewis and Clark had neither means nor standards, other than empirical ones, of measuring wind velocity. The cup-anemometer was invented in 1850. Currently (2003), there are eight wind-driven power generators in the vicinity of Great Falls with a total output of 37.6 kilowatts of electricity. |