In late May 1805, it was warm in what is today the state of Montana. Afternoon temperatures were in the 80s, and at night one blanket was enough. To the Easterners of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the air also felt remarkably dry. Captain Meriwether Lewis noticed cracks and shrinkage in his wooden sextant case, and he had trouble keeping his brass inkwell filled. Well, how dry? What was the rate of evaporation?

“I found by several experiments that a table spoon full of water exposed to the air in a saucer would avaporate in 36 hours,” wrote Lewis in his journal for 30 May 1805.

The saucer became an impromptu hygrometer, an instrument for measuring humidity. There were many well-known ways of watching changes in the air’s water vapor content; a ball of wool that grew heavier in moist air had done the trick 300 years before for Leonardo da Vinci, no less. In the early 19th-century calibrated hygrometers were coming into use, but they probably were too delicate to bang around in a Missouri River canoe. Lewis’ saucer could only tell him that water disappeared pretty fast into the pure, dry atmosphere of Montana’s high plains, but not as fast as it did previously on 23 September 1804 in South Dakota, when Captain William Clark noted that two spoonfuls “aveporated” during the same saucer-time of 36 hours.

Jefferson’s Instructions

Lewis and Clark were Army explorers, not experts in meteorology, a science that had barely begun and isn’t far advanced even today. Yet President Jefferson naturally was curious about weather conditions in the newly acquired expanse of Louisiana, and weather observations were on the long list of assignments for his exploring team. Among “objects worthy of notice” on the trip, Jefferson instructed Lewis, would be:

“Climate, as characterised by the thermometer, by the proportion of rainy, cloudy, & clear days, by lightning, hail, snow, ice, by the access and recess of frost, by the winds prevailing at different seasons, the dates at which particular plants put forth or lose their flower, or leaf, times of appearance of particular birds, reptiles or insects.”

The captains obeyed. The account of their travels is crammed with fresh climatological data, including the first systematic day-by-day record of an entire deep-freeze winter in North Dakota. While some of the temperature readings during that winter of 1804–1805 may have been questionable, it would be nice to think that the government had folded those early results into its statistical averages for the area’s “normal” climate. Alas, this was not done.

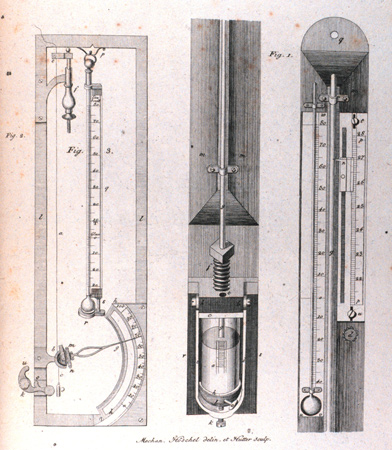

Just one kind of formal measuring instrument—the thermometer—accompanied Jefferson’s weather scouts. The hot-cold scale worked out by holland’s Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit in 1724 (with its 100-degree mark, for “hot,” pegged just above human body temperature) was in widespread use in North America. Lewis and Clark carried no barometer, though portable versions using atmospheric pressure to measure mountain heights were then available.[2]See W. E. K. Middleton, Invention of the Meteorological Instruments (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1969), and The History of the Barometer (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1964). It would have been just one more fragile gadget to bother with, and anyway, the explorers set out expecting not much more than a hump between the Missouri and Columbia headwaters. As Jefferson’s instructions suggested, state-of-the-art weather observing was still pretty much at the Farmer’s Almanac level, consisting mainly of keeping your eyes open.

A Running Weather Commentary

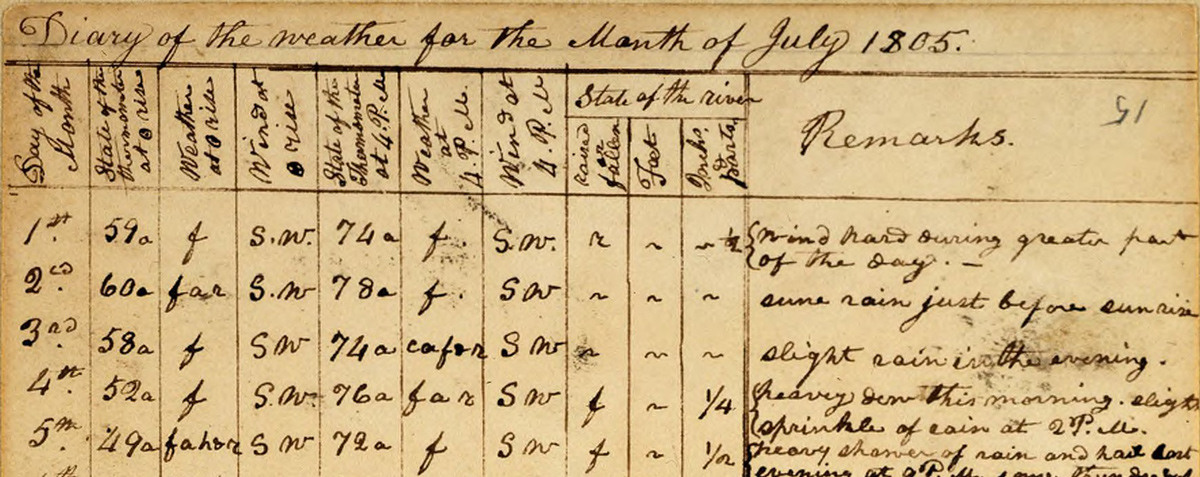

“Diary of the Weather for the month of July 1805” (Detail)

© American Philosophical Society, FE-015.

For travelers living under the sky, keeping a weather-eye peeled was as natural as a winter shiver. Daily routine on the march could be quickly altered by the weather’s whims. Heading up the lower Missouri on a 96-degree June day “the men becom verry feeble,” wrote Clark, and had to take a three-hour breather on the bank. Weather influenced major strategy decisions as well. On arrival at the mouth of the Columbia in November 1805, the party was torn between moving back upriver to a drier wintering place, or staying on the coast to endure the constant rain and the local price-gouging Indians. But the captains noticed that those Indians went around almost naked, a sign that the leather-clad explorers wouldn’t have to bundle up against another cold winter, and that helped tilt the decision to stay. And cloudy weather defeated Lewis’s hope of getting an observation of the sun to determine his position while scouting the Marias River country in July 1806. After waiting three days he gave up and bid “a lasting adieu to this place which I now call camp disappointment.”

Interestingly, such mere bare-bones operational reports on the weather came more often from Lewis, supposedly the more introspective of the captains. It was Clark who seemed more emotionally moved by the weather’s changing moods, and who often opened a new day’s journal entry with a weather comment intended to set the scene.

“A cloudy rainy disagreeable morning,” began Clark’s account of a tough day descending some rapids on the Columbia. In fact, weather somehow brought Clark about as close to expressive writing as he ever got. From his field notes at the Camp Dubois jump-off point in Illinois: “all the after part of the Day the wind so high that the View up the Missourie appeared Dredfull, as the wind blew off the Sand with fury as to Almost darken that part of the atmespear this added to agutation of the water apd truly gloomy.” Near Council Bluffs: “after the wind it was clear sereen and cool all night.” “Flying clouds all day,” was an image frequently evoked in his journal.[3]Clark seemed fascinated by the behavior of clouds. Reporting an impending storm on the Yellowstone, he wrote: “the cloud appd to hang to the S W, wind blew hard from different points from 5 to … Continue reading And “A fair Sun shineery morning” told you that 14 January 1804 would be an upbeat day at Camp Dubois.

Both captains tried to generalize from day-to-day evidence and, as good men of the Enlightenment, draw conclusions where they could. On the ascent of the Missouri as it reached the plains, Clark alertly noted the absence of something: “I have observed that Thunder and lightning is not as common in this Countrey as it is in the atlantic States.” At the confluence of the Columbia and the Snake, Clark correctly saw a weather clue in the fact that the roofs of the Indian lodges were almost flat, “which proves to me that rains are not common in this open Countrey.” At one point the journal of Private (later Sergeant) Patrick Gass noted “a quantity of fallen timber” on the right, or Iowa, bank of the Missouri. But Clark reasoned harder, seeing “apparently the ravages of a Dreddful harican” that had jumped the river the year before. Hurricanes of course are ocean storms, so the deductive captain had the modern name wrong. But the expedition was crossing what’s now known as Tornado Alley, and a twister quite possibly was the cause of those snapped-off tree trunks.

The explorers were quite faithful in keeping for the President a record of biological evidence of the changing seasons—though it perhaps had less meaning for a latitude-hopping party on the move than for a stationary country gentleman at Monticello. The weather diaries reported the times when wild cherries bloomed, elks shed their antlers and bull buffalo competed for the cows. Perhaps the most charming entry of this kind was a sign of spring reported by Lewis in Idaho in May 1806: “the dove is cooing which is the signal as the indians inform us of the approach of the salmon.”

Geese and swans were flying southward in October 1804, as the expedition moved up the Missouri to meet the approaching winter; cottonwood leaves were falling fast and flannel shirts had been issued to the men. Frost was in the air in November as the party built its villages, a fixed spot for watching the seasons for the next five months. On 13 November 1804, Clark carefully reported the onset of ice running in the river, an important fact for explorers seeking a water route to the Pacific. By month’s end the Missouri was frozen hard enough for people to walk on.

Fort Mandan Cold

December 1 [1 December 1804] saw the thermometer hit 1 degree below zero, the coldest day of the season so far. That was the sunrise reading. Every afternoon somebody always checked the thermometer again at 4 o’clock, and both captains wrote down the days’ readings in their tabular weather diaries. During the previous winter at Camp Dubois Lewis had tested the calibration of one of the party’s thermometers by dipping it in slush to match the mercury’s level against “the friezing point, and boiling water for the point marked boiling water.” He decided that the mercury stood 8 degrees too low compared to those marks on the instrument. Lewis therefore began his diary by making a plus-8 degree correction in his written temperatures, but Clark just put down the raw readings.[4]Thwaites, 6:166, 170n2. An 1803 list found at the Army Quartermaster Depot in Philadelphia showed that Lewis ordered three thermometers for the expedition. Though there’s no record of how many … Continue reading By wintertime at Fort Mandan, however, the captains were both recording the same temperatures, mostly, either because they agreed that uniformity was better or, more likely, because they had switched to another thermometer. Either way, it wasn’t a reassuring display of the accuracy of their instruments.

Moreover, some of those recorded temperatures are suspiciously inconsistent with what people were saying elsewhere in their journals. For 11 November 1804, the temperature tables show the mercury rising abruptly to a balmy 60 degrees in the afternoon. Yet Clark said it was “a cold Day” in his journal for that date, and Sergeant John Ordway thought it was “chilly this evening.”

At any rate, that was a bitterly cold winter in North Dakota, with moonlight sometimes making strange refraction patterns through ice crystals in the air. One freezing day in January Lewis had to use “sperits” instead of water for a reflective surface needed for his sextant reading of the sun. The winter’s coldest recorded day was 17 December 1804, when Clark made a sunrise entry of 45 below zero in his tabular weather diary and in his journal commenting that it was a “verry Cold morning. ” That date’s low also caught the eye of Jefferson. However, the President used Lewis’s slightly different reading in reporting the captain’s progress to a scientific crony in France: “He wintered in Lat. 47 degrees 20′ and found the maximum of cold 43 degrees below the zero of Fahrenheit.”[5]Thwaites, 7:327. Jefferson’s 11 February 1806, letter to Constantin F. V. Volney reflected his examination of documents received in Washington from Fort Mandan in July 1805.

The suspicious wobbling of digits recorded in the tabular diaries, taken from one or more thermometers of questionable calibration, makes it risky to use the Fort Mandan temperature readings for a precise measurement of exactly how cold it was that winter. Yet nobody else was at that particular place with a thermometer that early in history, and during the entire winter the expedition’s amateur weathermen didn’t miss one day of a sunrise and afternoon temperature check.

So for what it’s worth, those readings averaged 4 degrees above zero for December, 3.4 degrees below zero for January and 11.3 degrees above zero for February. That produced an average for the winter of 4 degrees above zero.[6]Computed from photocopy reproductions of temperature tables in Clark’s Codex C and Lewis’s book of thermometrical observations, furnished by the American Philosophical Society in … Continue reading

Was that “normal?” According to the National Climatic Data Center in Asheville, North Carolina, it was not until 1935 that the government decided to define “normal” as a temperature average covering a previous period of 30 years. The current period of normals against which today’s temperatures are compared is 1951–1980. For Bismark, the station closest to Fort Mandan, the normal temperatures for December, January and February average 12.3 degrees above zero.[7]National Weather Service data reproduced in The 1986 World Almanac and Book of Facts (New York: Newspaper Enterprise Association, Inc., 1985), 758. So despite all the obvious difficulties of comparison, including the possibility of a long-term climatic change, one may say that the Lewis and Clark winter of 1804–1805 in North Dakota was decidedly colder than “normal” as it’s reckoned today.

The Fort Mandan temperatures, along with all the expedition’s weather diaries, were published in 1814 as an appendix to Nicholas Biddle‘s authorized narrative of the trip. Biddle left out the bulk of scientific data available to him in the manuscript journals, but perhaps he included the rather tedious record of temperature, wind and sky conditions because Lewis had promised a weather diary in an 1807 post-expedition prospectus of his planned account of the tour. The weather, at least, was an integral part of the expedition’s early published history.

Unique as they were, however, it doesn’t appear that the weather records of those early years have been incorporated into the government’s climatological data base. Not until 13 years after the expedition’s return did the government start trying to collect weather observations in a nationally systematic way. The Army Surgeon General told doctors at every military post to keep a weather diary, “as the influence of weather and climate upon diseases, especially epidemic, is perfectly well known . . . “[8]Quoted by Charles Smart, “The Connection of the Army Medical Department with the Development of Meteorology in the United States,” Weather Bulletin 11:209. Thus temperature records from some U.S. military posts are available from 1819, but observations from North Dakota in the microfilmed climatic archives in Asheville go back only to 1874.[9]Inventory of Sources of long Term Climatic Data in Microfilm an Publication Form, National Climatic Center (Asheville, N.C., 1982), 61. Since the start of official observations in 1874, the … Continue reading

Improvisations

With buds on the willows, Lewis and Clark left Fort Mandan in April 1805, and the moving party’s weather once again became a function of changes in latitude and elevation, as well as season. Approaching Montana’s Beaverhead Mountains in mid-August the men were surprised at the upland chill. “we lay last night with 2 blankets or Robes over us & lay cold,” wrote Private Joseph Whitehouse. On 3 September 1805 climbing toward Lost Trail Pass in the Bitterroots, Clark reported that “we met with a grat misfortune, in haveing our last Thermometer broken, by accident,” when the instrument’s case bumped a tree.

Now began some virtuoso improvising for ways to measure temperature without a thermometer. “the loss of my thermometer I most sincerely regret,” wrote Lewis at Fort Clatsop on a mild day in early January 1806. “I am confident that the climate here is much warmer than in the same parallel of latitude on the Atlantic Ocean, tho’ how many degrees is now out of my power to determine.”

But he could guess. Not two weeks later, Lewis was “satisfied that the mercury would stand at 55 a 0.” Then, during a cold snap, the sight of his breath indoors led him to “suspect” a thermometer would show just 20 degrees above. Two inches of water in a vessel experimentally placed outside froze solid, but the next night rated “not so could” with a reading of just 3/8ths of an inch of ice. And the number of blankets needed by a sleeper continued to be a rough measure of temperature. “have slept comfortably for several nights under one blankett only,” reported Lewis in June 1806, encamped in Idaho. But deeper into the summer Clark complained he “slept cold under 2 blankets” at the head of the Bitterroot Valley in Montana.

No thermometer was needed for the captains’ twice-daily report on the “aspect of the weather,” recording sky conditions and precipitation. The entries were simple abbreviations: “c” for cloudy, “f” for fair, “r” for rain, and the like. On the buffalo plains one letter often sufficed, but Fort Clatsop’s mixed-up weather sometimes produced an alphabetical shower. For example, this was the “aspect” entered for the afternoon of 7 March 1806: “r.a.f.r.h.c.&f,” which decoded, meant rain after fair, rain, hail, cloudy and fair. Lewis added an exasperated remark for that date: “Sudden changes & frequent, during the day, scarcly any two hours of the same discription.”

Fort Clatsop Rain

The most disagreeable time I have experienced,” wrote William Clark on 15 November 1805, as the expedition was pinned by storms on the north back of the Columbia River estuary. The endless winter rain of the northwest Pacific coast gave the Lewis and Clark expedition its biggest weather shock of the whole trip. A “typical rainy winter day” at the coast is generated by low pressure systems over the Pacific. Storm fronts pushed by strong winds aloft dump the ocean’s moisture onto the western side of the Coastal and Cascade mountain ranges.

Rain was experienced by the expedition’s weather observers during the winter of 1805–1806 at Fort Clatsop. After filling his January 1806, weather diary with such entries as “rained incessently all night,” and “rained very hard last night,” and—miraculously—”the sun shown about 2 h. in the fore noon,” Meriwether Lewis ventured this generalization: “The Winds from the Land brings us could and clear weather while those obliquely along either coast or off the Ocean bring us warm damp cloudy and rainy weather.”

Patrick Gass totted up this soggy statistic for the Fort Clatsop winter: “From the 4th of November 1805 to the 25th of March 1806, there were not more than twelve days in which it did not rain, and of these but six were clear.”

By mid-April 1806, the eastbound party had recrossed the moisture-catching mountains and immediately noticed a difference. “even at this place which is merely on the border of the plains of Columbia,” wrote Lewis, “the climate seems to have changed the air feels dryer and more pure.”

Worthy of Notice?

Faithfully, almost stubbornly, the explorers checked the sky conditions and wind direction each day after leaving Fort Clatsop, no matter what else was going on. The practical value of these records to anyone may be questioned; Elliott Coues called the tabular entries “useless,” and said he included them in his 1893 narrative only to fulfill a pledge not to leave anything out.[10]Elliott Coues, Editor. The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Francis P. Harper (New York, 1893), 3:1282. Perhaps the observations stand best as a symbol of the captains’ fidelity to duty, come what may.

On 27 July 1806, for example, Lewis had quite a lot to do besides study the sky. That’s the day he was startled awake on Two Medicine River in Montana by the bloody knife-and-gun struggle with his Blackfeet camp companions, followed by a marathon horseback gallop to safety. (See Fight on the Two Medicine.) Yet he found time then, or on recollection later, to note that the sky was fair and that the wind shifted from northwest to southwest between dawn and late afternoon. That might not have been “worthy of notice” under the circumstances, but it was something for both Jefferson and posterity to admire.

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “‘. . . it thundered and Lightened:’ The Weather Observations of Lewis and Clark”, We Proceeded On, May 1986, Volume 12, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is provided at http://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol12no2.pdf#page=6. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See W. E. K. Middleton, Invention of the Meteorological Instruments (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1969), and The History of the Barometer (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1964). |

| ↑3 | Clark seemed fascinated by the behavior of clouds. Reporting an impending storm on the Yellowstone, he wrote: “the cloud appd to hang to the S W, wind blew hard from different points from 5 to 8 PM which time it thundered and Lightened.” Thwaites, 6:225. |

| ↑4 | Thwaites, 6:166, 170n2. An 1803 list found at the Army Quartermaster Depot in Philadelphia showed that Lewis ordered three thermometers for the expedition. Though there’s no record of how many he actually took, it was more than one, because Clark on 3 September 1805 reported that accidental breakage of “our last” thermometer. In his Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, editor Donald Jackson dismissed as “not likely” the persistent story that Antoine Saugrain, a St. Louis doctor, made the instruments by scraping mercury from the back of a household mirror. 1:75n1. See on this site Thermometers and Temperatures by Robert R. Hunt.) |

| ↑5 | Thwaites, 7:327. Jefferson’s 11 February 1806, letter to Constantin F. V. Volney reflected his examination of documents received in Washington from Fort Mandan in July 1805. |

| ↑6 | Computed from photocopy reproductions of temperature tables in Clark’s Codex C and Lewis’s book of thermometrical observations, furnished by the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. There are numerous transcribing or printing errors in the tables appearing in the several editions of Thwaites. |

| ↑7 | National Weather Service data reproduced in The 1986 World Almanac and Book of Facts (New York: Newspaper Enterprise Association, Inc., 1985), 758. |

| ↑8 | Quoted by Charles Smart, “The Connection of the Army Medical Department with the Development of Meteorology in the United States,” Weather Bulletin 11:209. |

| ↑9 | Inventory of Sources of long Term Climatic Data in Microfilm an Publication Form, National Climatic Center (Asheville, N.C., 1982), 61. Since the start of official observations in 1874, the temperature at the National Weather Service station at Bismark twice hit a record low of 45 below zero on 13 January 1916 and on 16 February 1936, equaling Clark’s low for 17 December 1804. |

| ↑10 | Elliott Coues, Editor. The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Francis P. Harper (New York, 1893), 3:1282. |