On 23 February 1801, just nine days before Jefferson’s inauguration, Lewis was asked to be the President’s private secretary.

Becoming the President’s Secretary

Thomas Jefferson arose in the crowded Senate chamber of the unfinished Capitol in Washington to speak eloquently of his country. America is a rising nation,” he said, “advancing rapidly to destinies beyond the reach of the mortal eye.”

It was 4 March 1801, Inauguration Day for the third president. Nine days previously Jefferson had asked Meriwether Lewis to serve as his private secretary in the raw new mansion called the President’s House.

Jefferson’s letter caught up with Lewis in Pittsburgh, where the recently promoted Army captain had just arrived on his circuit as regimental paymaster. The 26-year-old soldier gladly accepted. Pushing against the slow-motion travel constraints of the day, he arrived on horseback in Washington on 1 April 1801.

Lewis was to spend just over two years working with Jefferson at the pinnacle of the adolescent Federal government. Their association quickened dramatically America’s march toward the distant destinies of Jefferson’s inaugural rhetoric. At some unknown point an ambitious Lewis nailed down the assignment of leading a government exploring party across the fabled Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. And as they planned the mission month after month, elbow to elbow, Lewis had time to absorb every nuance of what the President expected from the project. The expedition leader who left Washington for the West on 5 July 1803, would know intimately the reasoning behind each line of his written instructions. That helped Lewis and his co-commander, William Clark, direct the enterprise with great assurance in the field, after an odd wobble at the very outset.

But for Lewis in the wonderful spring of 1801, all that was in the unknown, unplanned future. The new Washington job changed everything for this son of the backwoods gentry of Virginia, who had just five years’ formal schooling in his head. Lewis’s adult experience so far had been limited mostly to the muddy-booted grind of frontier army life. Now he dwelt in the President’s House on Pennsylvania Avenue, where he and Jefferson welcomed James and Dolley Madison as temporary residents until the new Secretary of State could get his own local digs. Joining these celebrities at dinner Lewis could be excused for pinching himself: here he was, a freshly scrubbed infantryman, sipping Madeira at the same table with the author of the Declaration of Independence and the mastermind of the Constitution!

“I feel my situation in the President’s family an extreemly pleasant one,” boasted Lewis at the time.

Moving In

President’s House (1803, 1807)

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, architect (1764-1820)

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-66.

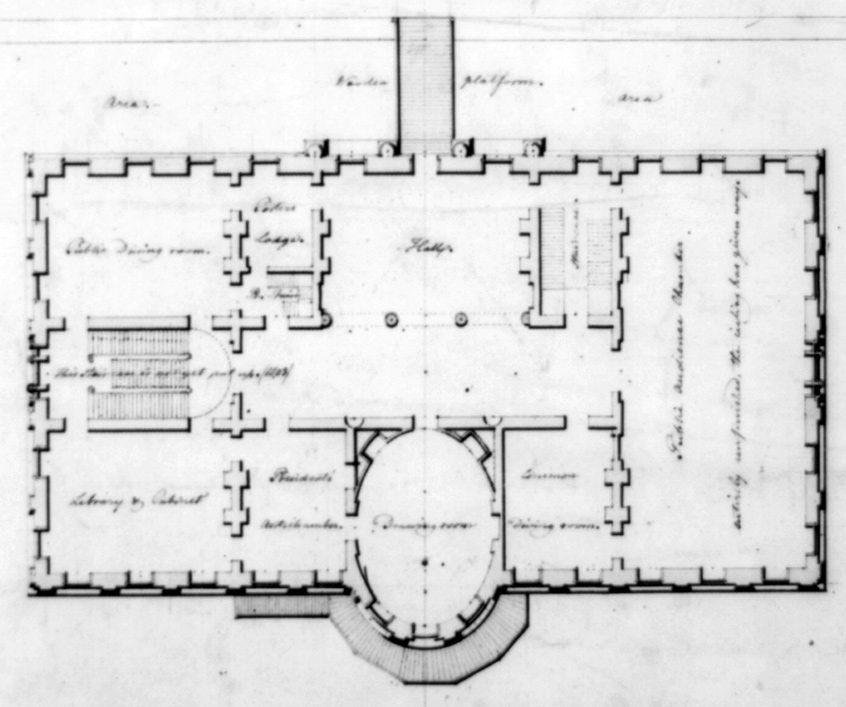

Main floor of the President’s House drawn in 1803 by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Temporary partitions in the south, or bottom, end of the cavernous “Public Audience Chamber” (today’s East Room) created an office and a bedroom for Meriwether Lewis, the President’s secretary.

The Madisons moved out at the end of May, leaving the servants with only the President and his secretary to take care of. “Capt. Lewis and myself are like two mice in a church,” said Jefferson in a letter to his daughter.[2]Jefferson to Martha Randolph, May 28, 1801, in Edwin Betts and James Bear, eds., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, 1986), 202. A newspaper joshed that the 23-room mansion was “big enough for two emperors, one pope and the grand lama in the bargain.” The exterior sandstone walls were already whitewashed,[3]“The President’s House” was the mansion’s official name at the time, but informally it has been called the White House “almost from the beginning because its white … Continue reading but the rather severe structure hadn’t yet been balanced by the present north and south porticoes.

Today the glittering East Room is used for concerts and an occasional presidential press conference, but in 1801 it was just an empty cavern where Abigail Adams had hung out her wash. At the south end of that vast space workmen erected wood-framed sailcloth partitions to carve out an office and a bedroom for Lewis.[4]William Seale, The President’s House: A History (White House Historical Association, Washington, 1986), 94.

Jefferson had assured the captain he would retain his Army rank while on detached duty, but he told Lewis remarkably little about what those duties would be. Maybe the president-elect, himself a newcomer to big-time executive management, wasn’t exactly sure how he would make use of a staff assistant. It was only after Lewis’s two-year shakedown run that Jefferson could be more specific about how the secretary’s job was working out in practice. Describing it in early 1804, the President said:

The office itself is more in the nature of that of an Aid de camp, than a mere Secretary. The writing is not considerable, because I write my own letters & copy them in a press. The care of our company, execution of some commissions in the town occasionally, messages to Congress, occasional conferences & explanations with particular members, with the office, & inhabitants of the place where it cannot so well be done in writing, constitute the chief business…”[5]Jefferson to William Burwell, 26 March 1804, in Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1978), 1:3.

Not listed specifically was the function of being simply a traveling companion to the widowed President, and if it came to that, a bodyguard. A Presidential entourage through the streets of Washington usually consisted entirely of Jefferson and a uniformed Lewis, each on horseback. Every Sunday the President rode up to Capitol Hill for church services in “The Oven,” a temporary structure used by the House of Representatives. The seating arrangement was described by Margaret Smith, wife of the publisher of the National Intelligencer, the city’s loyalist Republican newspaper: “The seat he chose the first Sabbath, and the adjoining one, which his private secretary occupied, were ever afterwards by the courtesy of the congregation, left for him and secretary.”[6]Margaret Bayard Smith. The First Forty Years of Washington Society (Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., New York, 1965 reprint of 1906 original edition), 13.

Report on Army Officers

Lewis was Jefferson’s first choice for the secretary’s position. “It has been sollicited by several, who will have no answer till I hear from you,” the president-elect said in his February 23 letter of invitation. Jefferson was well enough acquainted with the young officer to know he was a good Republican. Also, pedigree counted for a lot in those days, and Jefferson regarded the Lewis clan—his own neighbors in Albemarle County, Virginia—as “one of the distinguished families of that state.” Aside from favoring a family friend, did Jefferson have other reasons for passing over his politically sophisticated civilian cronies for a frontier soldier?

From this particular assistant Jefferson wanted an important bonus: information.

“In selecting a private secretary, I have thought it would be advantageous to take one who possessing a knolege of the Western country, of the army & its situation, might sometimes aid us with information of interest, which we may not otherwise possess,” the president-elect explained in a separate letter to General James Wilkinson, the Army commander.[7]Jackson, Letters, 1:1.

Many historians have been tempted to conclude that in seeking someone with “knolege of the Western country,” Jefferson already had a Pacific expedition in mind when he entered office in 1801. Thanks to more recent research by expedition specialist Donald Jackson and others, it now seems clear that Jefferson wanted Lewis’s help with a more immediate matter of political delicacy involving the Army.

Disagreement on the size of the Federal military establishment had been one of the first factional wedges splitting Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists and the Jefferson-Madison Republicans in the 1790s. In 1798 the Federalist majority in Congress responded to a war scare with France by expanding the Army over Republican objections that a smaller force of regulars would be enough. The partisan makeup of the Army’s enlarged officer corps quickly became a political football.

In late 1798 Secretary of War James McHenry said in a private letter—which got into the newspapers—that he would be glad to consider officers’ commissions for “that description of persons whom you denominate old Tories. . .” That indiscreet letter embarrassed President John Adams, who later cited it as one of his reasons for firing McHenry.[8]McHenry wrote his recollection of a remarkable 5 May 1800, private meeting with John Adams, during which the resident chewed out his Secretary of War for a long list of political sins, including the … Continue reading

With Jefferson’s arrival it was the Republicans’ turn to kick the football. The new Secretary of War, Henry Dearborn, drafted proposals to downsize the Army and its Federalist-packed officer corps while concentrating the remaining force on the Mississippi River and other Western points.[9]Richard Alton Erney, The Public Life of Henry Dearborn (Arno Press, New York, 1979), 66-7. Given Lewis’s knowledge of “the Western country” and the Army’s “situation,” it’s quite possible his advice was sought in shaping this new deployment. Dearborn sent his plan to Congress in December 1801; the “Military Peace Establishment Act” was passed with little change in March 1802. The law authorized an Army strength of 3,289 regulars, down 25 percent from the enrollment at the start of Jefferson’s term.

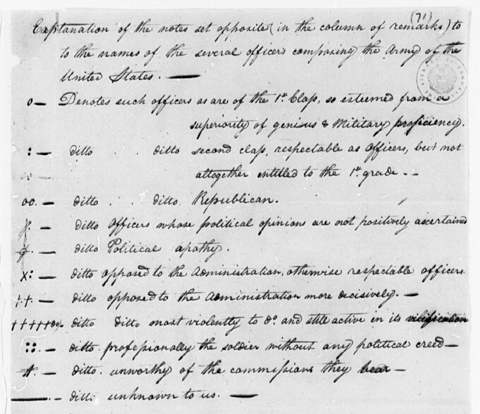

At some point, perhaps in early 1802, Lewis gave added advice on how many Federalist officers could be got rid of. Even with the previous Hamiltonian expansion the Army still had just 269 officers, and Lewis knew a great many of them personally or by reputation. In Jefferson’s papers at the Library of Congress is a War Department roster of these officers with a curious set of dots, crosses and other markings added to their names. The code could only be read with the help of a one-page key to the symbols in Lewis’s handwriting.

The coded roster of names graded each officer’s professional military qualities, plus his political attitude toward the Jefferson administration. For example, a small open circle stood for “such officers as are of the 1st Class, so esteemed from a superiority of genius & Military proficiency.” If the circle was followed by a series of crosses, however, it also meant that officer was “opposed most violently to the administration and still active in its vilification.” Most vulnerable to the Republican ax were names tarred both with those Federalist crosses and a symbol for incompetence (“unworthy of the commissions they bear.”)

Lewis’s evaluations were advisory only; after enactment of the 1802 Army cutback law it was up to Jefferson and Dearborn to decide whether a Federalist officer’s political taint could be overlooked because of his professional skill. Dearborn made pious claims of being guided by “merit alone,” but most of the officers removed by 1 June 1802, were Federalists.[10]Donald Jackson, “Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis, and the Reduction of the United States Army,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, April 1980, 91-6. Also see Theodore J. … Continue reading

Affairs of State

Lewis at times was called upon to run sensitive political errands on the President’s behalf. One such case dealt with pamphleteer James Thomson Callender, which got into the historical record because it turned so ugly; doubtless there were other examples not written down. Callender had been convicted under the Sedition Act for criticizing the Adams administration. While out of power the Republicans had made martyrs of Callender and other victims of Federalist prosecution. Shortly after his inauguration Jefferson pardoned Callender, who had already served a nine-month jail term and paid a $200 fine. Jefferson wanted the government to refund the fine, but there were delays, and then an impatient Callender showed up in Washington demanding redress.

Jefferson recorded what happened next: “Understanding he was in distress I sent Captain Lewis to him with $50 to inform him we were making some inquiries as to his fine which would take a little time…” The $50 was intended to tide Callender over, but Lewis reported back to Jefferson that the downtrodden victim didn’t seem grateful. “His language to Captain Lewis was very high-toned,” Jefferson wrote. “He intimated that he was in possession of this which he could and would make use of in a certain case: that he received the $50 not as a charity but a due, in fact as hush money.” Callender, in short, was trying to blackmail the President into giving him a Federal job. When Jefferson cut off further dealings, Callender took revenge by spreading the famous story that Jefferson had a slave mistress, Sally Hemings.[11]Dumas Malone, Jefferson the President: First Term (Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1970), 207-13.

Not all of Lewis’s duties involved such high-tension intrigue. More pleasantly he helped arrange the President’s almost nonstop series of dinner parties for politicians, diplomats and scientists, and Lewis usually had a place at the oval table himself. Jefferson preferred that shape because it allowed him to draw everyone into the conversation. Dinner prepared by a French chef was most often served in the “Common Dining Room” (today’ s Green Room) marked on Benjamin Latrobe’s floor plan. Only toward the dinner’s end were the guests invited to dive into Jefferson’s renowned stock of fine wines, up to eight varieties of them.

“At his usual dinner parties the company seldom or ever exceeded fourteen, including himself and his secretary,” reported Margaret Smith, the publisher’s wife.[12]Smith, First Forty Years, 388. When Congress was in town the guest list was dominated by lawmakers invited for a pleasant social evening. To avert any disruptive partisan arguments Jefferson’s custom was to invite only Republicans one evening, only Federalists the next.

Becoming Expedition Leader

Twice a year Jefferson escaped Washington for Monticello, a three or four day trip southward into Virginia. Lewis went along, bunking according to local legend at the nearby estate of William Bache. It was during a Monticello sojourn in the summer of 1802 that the President read Alexander Mackenzie‘s account of his 1793 trip from Canada’s interior of the Pacific Coast. Mackenzie’s book apparently prompted Jefferson to think anew about an American reconnaissance across the continent. The expedition would require a leader. Ten years before, he had been importuned by a teenage Meriwether Lewis to go on a western expedition planned unsuccessfully by the American Philosophical Society. If Jefferson had forgotten that, Lewis surely reminded him of it now.

There’s no contemporary record showing whether Jefferson actively considered specific candidates other than his secretary to command the Pacific expedition. Several months after picking Lewis for the job, the President explained how his selection was a compromise between getting a solid man of action and a formally trained scientist. In a letter to Philadelphia naturalist Benjamin Smith Barton, Jefferson wrote:

It was impossible to find a character who to a compleat science in botany, natural history, mineralogy & astronomy, joined the firmness of constitution & character, prudence, habits adapted to the woods, & a familiarity with the Indian manners & character, requisite for this undertaking. All the latter qualifications Capt. Lewis has. Altho’ no regular botanist &c. he possesses a remarkable store of accurate observation on all the subjects of the three kingdoms, & will therefore readily single out whatever presents itself new to him in either.[13]Jefferson to Benjamin Smith Barton, 27 February 1803, in Jackson, Letters, 1:16-7. See also Lewis’s Friends and Mentors.

Recording Weather

Lewis’s corrective crash courses in scientific formality may have begun that very summer at Monticello. Jefferson for many years had kept a rigidly systematic record of weather conditions at Monticello, or whatever his location at the time. A 1790 letter described how he took two thermometer readings to obtain each day’s high and low temperatures: “I have found 4 aclock the hottest and daylight the coldest point of the 24 hours.” Jefferson also entered abbreviations for the state of the weather, “c” meaning cloudy, “f” meaning fair, “r” meaning rain, and so on. The letter “a” stood for “after.” Thus, wrote the precision weatherman, “c a r h s means cloudy after rain, hail and snow.”[14]Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, 18 April 1790, in Julian Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1961), 16:351-2.

At some point after picking Lewis to head the Pacific expedition Jefferson drilled him on how to keep weather records the Monticello way. When Lewis and Clark were waiting in January 1804 to embark up the Missouri River from Illinois they began their first table of weather observations with a note decoding the old Monticello abbreviations for “fair after rain,” “cloudy after snow,” and all the rest.[15]Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1986), 2:168-9. Thereafter the expedition’s monthly weather tables obediently followed Jefferson’s own tabular format of 1790, except that the explorers added daily dawn-and-afternoon notations of wind direction.[16]See also Weather Observations.

Planning and Shopping

Jefferson and his secretary returned from their Monticello summer in October 1802. Expedition planning quite likely had become active by then, but Lewis had to take time out for a different Presidential assignment. Jefferson’s two daughters, Martha and Maria, were traveling by carriage from Virginia to the President’s House for an extended visit. Their horses would be tiring, so Jefferson dispatched Lewis to meet them at an inn 83 miles from Washington with a fresh team and another carriage. The party arrived in the capital on 21 November 1802.[17]Malone, Jefferson the President: First Term, 170.

In December the President asked Lewis to make a roughly itemized estimate of the Pacific expedition’s cost. Adding up Indian presents, camp equipment, weapons and whatnot the secretary arrived at a nice round guess of $2,500. Jefferson was ready to ask for this down-payment appropriation in his 15 December 1802 annual message to Congress, but Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin urged him to submit the request separately.

So it was that Captain Meriwether Lewis stood at the door of the Senate on 18 January 1803, bearing a Presidential message marked “Confidential.” Lewis had been Jefferson’s courier to Congress often before, but this time he had a strong personal stake in the contents of his package. The President was asking the House and Senate to approve a trip “to the Western Ocean” by “an intelligent officer with ten or twelve chosen men,” and Lewis knew he would be that officer.

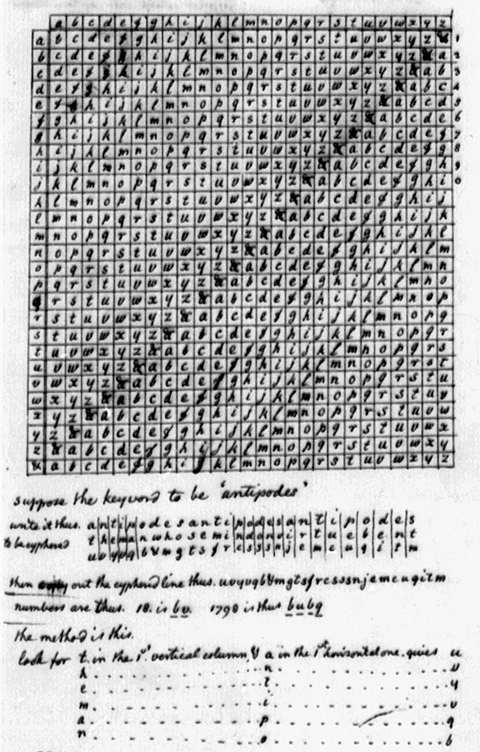

With his mind fixed on the big adventure Lewis may have thought he had time for little else. He had to learn, for example, how to use a cipher that Jefferson had devised for secret communication from the wilderness to Washington. He had to plan a preliminary trip to Harpers Ferry and Philadelphia to acquire equipment and get special coaching in celestial navigation.

Then in mid-February he was brought to earth by orders to help with a pet Presidential project involving scientific agriculture. With Jefferson’s encouragement several government bigwigs were forming an ostensibly private “American Board of Agriculture” to act as a central clearing house for good farming practices. Lewis’s brief link with the Board of Agriculture was intended as a public signal that the project had the blessing of his boss, the President.[18]For a more detailed account see The Phantom Farmer. Just then Congress gave final approval to the appropriation for his Western trip. When he left for Harpers Ferry three weeks later, he also ended for all practical purposes his regular duties as Jefferson’s secretary.

Lewis returned to Washington for a last round of expedition planning in late June. When he at last rode away from the President’s House on 5 July 1803, he was in effect trading the Madeira glass of a Washington insider for the rifle and compass of a sunburned explorer.

It took him a while to shift mental gears. His two-year immersion in Washington’s political hothouse colored the thinking behind a surprise announcement sent to Jefferson from the Ohio River in early October. Lewis already was running behind schedule, which he thought might draw flak from the administration’s critics in Congress. “Feeling as I do in the most anxious manner a wish to keep them in a good humour on the subject of the expedition in which I am engaged,” Lewis proposed to spend the coming winter on a splashy southern jaunt toward Santa Fe. The former East Room political operative assured the President that his findings “will at least procure the further toleration of the expedition.” Jefferson’s response to his wobble was a brisk order to stick to the programmed ascent of the Missouri River and avoid “any episodes whatever.”[19]Lewis to Jefferson. 3 October 1803, In Jackson, Letters, 1:131. Jefferson’s reply is on pp. 136-8.

Triumphant Return

On 28 December 1806, Lewis returned to Washington acclaimed as the conqueror of the Rockies. Though Jefferson now had a replacement secretary named Isaac Coles, Lewis moved back into the President’s House as something of an honored guest. He and the President spent many hours rehashing the Western adventure, and Lewis must have told his story well. “On the whole,” wrote Jefferson at that time, “the result confirms me in my first opinion that he was the fittest person in the world for such an expedition.”[20]Jefferson to William Hamilton, 22 March 1807, in Jackson, Letters, 2:389.

In mid-March, 1807, the President complained to his daughter of having a bad cold, adding: “Mr. Coles and Capt. Lewis are also indisposed, so that we are but a collection of invalids.”[21]Jefferson to Martha Randolph, 16 March 1807, in Betts and Bear, Family Letters, 302. Shortly afterward a recovered Lewis went to Philadelphia to arrange for his (never written) narrative account of the expedition. It wasn’t until mid-July that he returned to Washington for the last time in his life, and bade his final goodbye to the President at Monticello in September.[22]Jefferson to Lewis, 17 July 1808, in Jackson, Letters, 2:444. Without offering evidence John Bakeless, in his respected Lewis & Clark: Partners in Discovery (William Morrow & Co., New York, … Continue reading Lewis continued westward at a comfortable pace to St. Louis, where he took up his new duties as governor of Upper Louisiana in March 1808.

Then began a time of troubles for the returned hero. Feeling harassed by local politicians and the new Madison administration, Lewis set out for Washington in the fall of 1809. When he died of gunshot wounds in Tennessee, Clark and others on the frontier assumed he killed himself. So did Jefferson, who in hindsight said Lewis’s “hypochondriac affections” were evident prior to the expedition. “While he lived with me in Washington I observed at times sensible depressions of mind,” the ex-president wrote in 1813.[23]Thomas Jefferson, “Life of Captain Lewis,” in James Hosmer, ed., History of the Expedition of Captains Lewis and Clark (A.C. McClurg & Co., Chicago, 1903 edition of the 1814 original … Continue reading

So it would seem that Lewis in Washington oscillated between his self-described “extreemly pleasant” feelings and the black moods noted by his powerful patron. Whether happy or sad, his Washington experience was the springboard that sent Meriwether Lewis into the foremost rank of history’s explorers.

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “Lewis … in Washington,” We Proceeded On, August 1994, Volume 20, No. 3, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The editor here has made minor changes to work as a web page. The original is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol20no3.pdf#page=15. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jefferson to Martha Randolph, May 28, 1801, in Edwin Betts and James Bear, eds., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, 1986), 202. |

| ↑3 | “The President’s House” was the mansion’s official name at the time, but informally it has been called the White House “almost from the beginning because its white sandstone stood out from the brick and frame of Washington houses,” according to Amy La Follette Jensen, The White House and its Thirty-Four Families (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1965), 21. |

| ↑4 | William Seale, The President’s House: A History (White House Historical Association, Washington, 1986), 94. |

| ↑5 | Jefferson to William Burwell, 26 March 1804, in Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1978), 1:3. |

| ↑6 | Margaret Bayard Smith. The First Forty Years of Washington Society (Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., New York, 1965 reprint of 1906 original edition), 13. |

| ↑7 | Jackson, Letters, 1:1. |

| ↑8 | McHenry wrote his recollection of a remarkable 5 May 1800, private meeting with John Adams, during which the resident chewed out his Secretary of War for a long list of political sins, including the 1798 “old Tories” recruitment letter, and demanded his resignation. McHenry’s version of the interview was published in Harold C. Syrett, ed., The Papers of Alexander Hamilton (Columbia University Press, New York, 1976), 2:552-65. |

| ↑9 | Richard Alton Erney, The Public Life of Henry Dearborn (Arno Press, New York, 1979), 66-7. |

| ↑10 | Donald Jackson, “Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis, and the Reduction of the United States Army,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, April 1980, 91-6. Also see Theodore J. Crackel, Mr. Jefferson’s Army (New York University Press, New York, 1987), 49-51. On p. 194 Crackel claims to have been the first to recognize Lewis’s officer-purging role in a paper delivered in 1977. See also on this site Lewis’s Report on Army Officers. |

| ↑11 | Dumas Malone, Jefferson the President: First Term (Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1970), 207-13. |

| ↑12 | Smith, First Forty Years, 388. |

| ↑13 | Jefferson to Benjamin Smith Barton, 27 February 1803, in Jackson, Letters, 1:16-7. See also Lewis’s Friends and Mentors. |

| ↑14 | Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, 18 April 1790, in Julian Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1961), 16:351-2. |

| ↑15 | Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1986), 2:168-9. |

| ↑16 | See also Weather Observations. |

| ↑17 | Malone, Jefferson the President: First Term, 170. |

| ↑18 | For a more detailed account see The Phantom Farmer. |

| ↑19 | Lewis to Jefferson. 3 October 1803, In Jackson, Letters, 1:131. Jefferson’s reply is on pp. 136-8. |

| ↑20 | Jefferson to William Hamilton, 22 March 1807, in Jackson, Letters, 2:389. |

| ↑21 | Jefferson to Martha Randolph, 16 March 1807, in Betts and Bear, Family Letters, 302. |

| ↑22 | Jefferson to Lewis, 17 July 1808, in Jackson, Letters, 2:444. Without offering evidence John Bakeless, in his respected Lewis & Clark: Partners in Discovery (William Morrow & Co., New York, 1947), asserts on pp. 388-90 that at an unspecified time in 1807 Lewis served as “Mr. Jefferson’s personal representative” at Aaron Burr’s treason trial in Richmond. This claim is echoed by Richard Dillon in Meriwether Lewis (Coward-McCann, Inc., New York, 1965) p. 296. The trial started 3 August and lasted until Burr’s acquittal on 1 September, a period when Lewis’s whereabouts are undocumented. Jefferson was at Monticello, where he relied on special couriers to bring progress reports from chief prosecutor George Hay in Richmond. Lewis by then was a celebrity in his own right, but there’s an absence of contemporary references to his presence at the trial, even by pro-Burr writers alert for signs of Presidential pressure for a conviction. Bakeless’s claim remains questionable. |

| ↑23 | Thomas Jefferson, “Life of Captain Lewis,” in James Hosmer, ed., History of the Expedition of Captains Lewis and Clark (A.C. McClurg & Co., Chicago, 1903 edition of the 1814 original [Biddle] edition) 1:liv. See also on this site The Last Journey of Meriwether Lewis by Clay S. Jenkinson. |