Plains Sign Language was the universal language of gesticulation among the Plains Indians. George Drouillard the expedition’s most skilled speaker.

The Language of “Gesticulation”

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia

Charles M. Russell (1905)

Courtesy Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

This dramatic but historically inaccurate painting by Charles M. Russell shows Sacagawea sign-talking with Indians on the lower Columbia. Coastal Indians of the Pacific Northwest did not understand Plains Indian sign language; inter-tribal communication was via Chinuk Wawa (Chinook Trade Jargon).

When Meriwether Lewis was planning his expedition to the Pacific Ocean and back he was authorized to hire an interpreter for communicating with the many tribes he expected to meet. One of his early recruits was George Drouillard, a part-Shawnee who knew Plains Indian sign language. Lewis met George Drouillard at Fort Massac, on the lower Ohio River, in November 1803 and quickly hired him as “an Indian Interpretter” for $25 a month. As every student of the Lewis and Clark story knows, Drouillard (whose name the captains spelled phonetically as “Drewyer”) became one of the most valuable members of the expedition as both an interpreter and a hunter. On 14 August 1805, he was part of Lewis’s small advance party when it encountered the Lemhi Shoshones near Lemhi Pass, on the Continental Divide. “The means I had of communicating with these people,” wrote Lewis,

was by way of Drewyer who understood perfectly the common language of jesticulation or signs which seems to be universally understood by all the Nations we have yet seen[.] it is true that this language is imperfect and liable to error but is much less so than would be expected[.] the strong parts of the ideas are seldom mistaken.[2]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 5:88. Entry for 14 August 1805. All quotations or references to … Continue reading

The meeting with the Shoshones occurred 15 months after the Corps of Discovery’s departure from St. Louis—yet this is the first mention in the journals of the use of sign language by Drouillard or any other member of the expedition. (Throughout the journals, unequivocal references to sign language total barely more than a dozen.)[3]The Comprehensive Index (Volume 13) of the Moulton edition of the journals lists 12 references to sign language (not counting notes), all in Volume 5. There are 13 references if you include … Continue reading When Lewis hired Drouillard as an interpreter he didn’t elaborate, and we are left to infer from later events that it was his knowledge of sign language that attracted Lewis to him. There presumably would have been opportunities for Lewis and Clark to call on his skills earlier in the expedition—during the explorers’ encounter with the troublesome Lakota Sioux in September 1805, for example—but if they did so, they failed to note it.[4]William Philo Clark, the first systematic chronicler of Plains Indian sign language, commented on the general paucity of information about the subject in accounts by early explorers and fur traders: … Continue reading

Nicholas Biddle addressed this curious silence when, four years after the expedition’s return and several months after Lewis’s untimely death, he took on the task of editing the captains’ journals. On 7 July 1810, from his home in Philadelphia, he wrote to William Clark asking, among other things, for “any information as to any system of signs by which you were able to communicate with the Indians, or which enables different tribes to converse together.”[5]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents: 1783–1854, 2nd. ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:552–553. Clark got around to answering his query on 7 December by passing the buck, suggesting that Biddle “enquire of Mr. Shannon for the language of signs used by Indians.”[6]Ibid., 2:563. Expedition member George Shannon had gone to Philadelphia to assist Biddle, but whatever he may have told him regarding sign language did not appear in the Biddle edition of the journals when it was published in 1814.[7]The Biddle edition (whose nominal editor was Paul Allen) is actually a paraphrased narrative of the expedition based on the journals. In his description of meeting the Shoshones, Biddle did not … Continue reading

The “Naturalness” of Signing

The naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton, in his masterful book Sign Talk, published in 1918, reminds us that this means of communication is “more ancient than the hills”—citing references found in Homer and on Greek vases, Japanese bronzes, and Hindu statuary.[8]Ernest Thompson Seton, Sign Talk (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1918), xv. Sir Edward B. Tylor, another oft-cited researcher, viewed “Gesture Language,” as he called it, as a mode of communication more deeply instinctive than higher “products of the human mind” such as painting and writing.[9]Sir Edward Burnett Tylor, Researches into the Early History of Mankind (London: J. Murray, 1878, 3rd. ed., revised), 3. The naturalness of signing was evident to General James Wilkinson, the governor of Louisiana Territory at the time of the expedition. When the captains sent the Arikara chief Too Né (Eagle Feather) to St. Louis on the first leg of a visit to Washington, D.C., to meet Thomas Jefferson, Wilkinson wrote the president in advance, calling the chief a “Master of the Language of Arms, Hands & Fingers . . . the language of nature.” Sign language, Eagle Feather informed the governor, was “the only practicable mode of Communication . . . at the Annual Grand Councils” of the plains tribes.[10]Jackson, 1:272–274.

During Eagle Feather’s sojourn in Washington he impressed the painter William Dunlap with “his ability to make himself understood by signs.” Dunlap observed: “His sign for speaking truth & the contrary is very expressive, he draws a line with his finger from his heart to his mouth & thence straight to the auditor or spectator; for falsehood the line comes crooked from any part of the Abdomen & on issuing from the lips, splits, diverges & crosses in every direction.”[11]Ibid., 274–275n2.

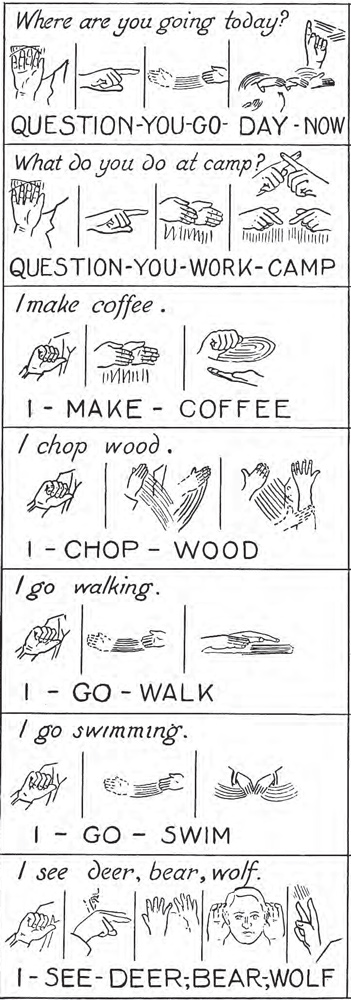

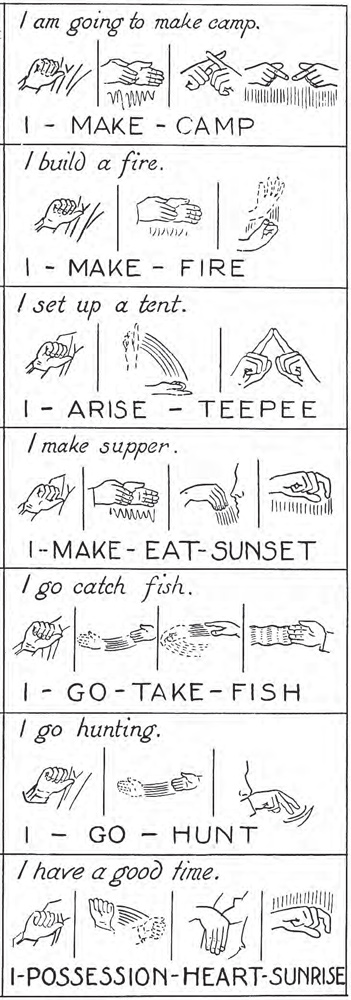

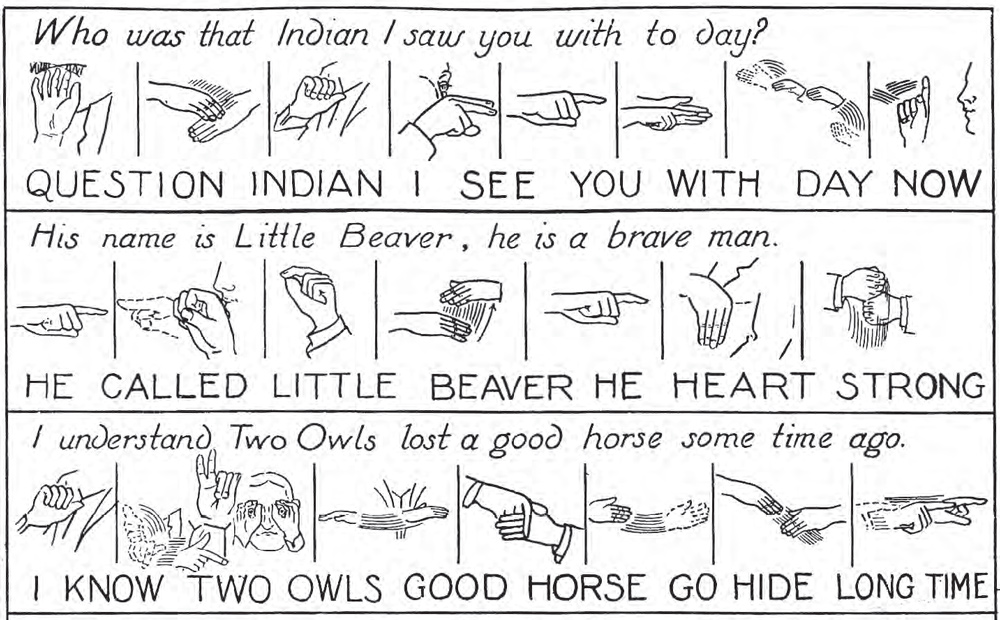

Such directness of expression, according to one student of signing, makes gesticulation the “most easily learned language.”[12]William Tomkins, Indian Sign Language (New York: Dover, 1969), 63. A summary account of a 1930 conference on the subject calls signing “an imitation of acts, qualities and attributes, . . . a description of a thing by color, shape or what it does.”[13]U.S. Department of the Interior, Plains Indian Sign Language (Browning, Mont.: A Memorial to the Conference 4–6 September 1930), unpaginated. Another source cites its “intuitive” nature and “universal appeal,” noting that common ideas such as “me, you, up, down, come” are promptly understood, just as “placing a finger vertically against the lips . . . means throughout the world that silence is desired.”[14]George Fronval and David Dubois, Indian Signals and Sign Language (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 1978), 6. (1985 editions published by Wing Books and Bonanza Books. Originally published in … Continue reading Underscoring this point are the signs for two tribes that aided the Corps of Discovery: hands pressed against the head for the Salish (historically known as the Flatheads) and an index finger drawn under the nose for the Nez Perces (French for pierced-nose Indians).[15]Moulton, 5:88n and 224n; Sally Thompson, “Misnomers along the Lewis and Clark Trail,” a paper delivered at a 2003 symposium and published in A Confluence of Cultures: Native Americans and … Continue reading

Seton offered this classic definition:

A true Sign Language is an established code of logical gestures to convey ideas; and is designed as an appeal to the eye, without the assistance of sounds, grimaces, apparatus, personal contact, written or spoken language, or reference to words or letters; preferably made by using only the hands and adjoining parts of the body.[16]Seton, xxvi.

He added that “there is only one true Gesture Language . . . the sign talk of the American Indians—essentially the same from Saskatchewan to Rio Grande.” [For examples of signing, see figures.)

Seton’s words echo Lewis’s journal entries for 14 August 1805 (cited above), and for 10 September 1805, when the explorers, led by the Shoshone guide Toby, encountered the Salish in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana:

our guide could not speake the language of these people but soon engaged them in conversation by signs or jesticulation, the common language of all the Aborigines of North America, it is one understood by all of them and appears to be sufficiently copious to convey with a degree of certainty the outlines of what they wish to communicate.[17]Moulton, 5:196–197.

A Shortage of Signers

Lewis exaggerated the universality of sign language, which as noted was mainly employed by tribes of the Great Plains, but his statement reiterates his confidence in signing as an effective means of communication. Given that confidence and the importance he placed in Drouillard’s skills as an interpreter, one wonders why he and Clark weren’t more knowledgeable about signing so they could use it effectively, if necessary, in Drouillard’s absence.

There were a number of occasions when such knowledge would have been helpful. When Lewis first encountered the Shoshones, in the person of a lone mounted warrior at Lemhi Pass, he attempted to show his friendly intentions by waving a blanket, displaying some trade beads, and rolling up a sleeve to expose his white skin. For added measure he called out tab-ba-bone, an expression he mistakenly believed meant white man. The warrior’s response to these overtures was to gallop off as fast as his horse could carry him. The outcome might have been more favorable had Lewis been able to strike up an immediate conversation using signs. Drouillard, while part of Lewis’s advance guard, was some distance behind so couldn’t bring his signing skills into play. Two days later, Lewis came upon three Shoshone women digging roots. This time Drouillard was present, and his signing assured the Indians of their benign purpose.[18]Ibid., 69 and 78–79; entries for 11 August 1805 and 13 August 1805.

During the return journey Lewis again found himself in a tight situation where signing was the only means of communication. On 26 July 1806, on a knoll overlooking Two Medicine River, he and the brothers Joseph and Reuben Field came upon eight young Indians leading a herd of horses. Drouillard, the fourth member of the party, was scouting the river bottom and unavailable for translating. As recounted by historian James Ronda, “While one Indian joined Reuben Field to find Drouillard, Lewis attempted some sign language,” trying to affirm the identity of the party.[19]James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984; First Bison Book printing, 1988), 239. Lewis assumed the Indians were Gros Ventres of the Prairies (Atsinas), and when he asked if this were so they answered in the affirmative. In fact, they were almost certainly Piegan Blackfeet. Ronda suggests the misunderstanding could have been due either to deceit by the Blackfeet or Lewis’s lack of skill in signing.[20]Whatever the reason, the encounter ended disastrously. Lewis’s party and the Indians camped together that night. A scuffle broke out the following morning, resulting in the death of one and … Continue reading

Clark also had his problems in Drouillard’s absence. In his journal entry for 22 September 1805, describing his meeting with the Nez Perces at Weippe Prairie, he observed, “We attempted to have Some talk with these people but Could not for the want of an Interpreter,” compelling him “to converse all together by Signs.” Sergeant Patrick Gass noted that the communication was “imperfect.”[21]Moulton, 10:149; entry for 26 July 1805. The next day, Clark “assembled the principal men . . . and by Signs informed them where we came from [and] where bound.” Whatever the Indians told them, according to Gass, could not be understood, “as we could only converse by Signs.”[22]Ibid., 149. In this tight situation Clark sensed a need “to prevent Suspission” while trying “to Collect by Signs as much information as possible.” The friendly testimony of a … Continue reading

A month later, at the confluence of the Snake and the Columbia rivers, Clark recorded parleys with the Yakimas, Wanapums, and Walla Wallas conducted in sign language; the translators were the explorers’ Nez Perce guides, Tetoharsky and Twisted Hair. (Whether Drouillard’s signing was brought into play isn’t noted, but presumably he provided oral translations of what was said.) The homelands of these Indians were west of the Continental Divide, but like the Shoshones they were familiar with Plains sign language because of their hunting forays into buffalo country. The meeting with the Walla Wallas on 19 October 1805, is the last recorded instance of successful signing on the outbound journey.[23]Clark, who was again in the lead when they met the Walla Wallas, tells how, to little avail, “I gave my hand to them and made Signs of my friendly disposition.” The Indians were in an … Continue reading As the expedition moved farther west and deeper into the salmon culture of the Columbia Basin, any communication by “signs” would have been strictly improvisational.[24]On two other occasions while on or near the Pacific—14 November 1805 and 9 December 1805—the explorers recorded Indians attempting to communicate by “Signs,” but the references are … Continue reading

Although reluctant to second-guess one of the best-managed expeditions in history, I suggest that Lewis and Clark should have made sure that they and the corps’ three non-commissioned officers were conversant in Plains Indian sign language. (Sergeants Gass, John Ordway, and Nathaniel Pryor all led detached units through Indian country during the homeward journey.) They should have spent more time during the long winter months at Fort Mandan and later at Fort Clatsop, on the Pacific, learning their ABCs from Drouillard. At the very least, every member of the expedition should have been able to convey by signs the simple message of “our friendly intentions” and “our wish to make a piece” (i.e., make peace).[25]Moulton, 5:296. Such training would not have been difficult—sign language is learned easily, and six hundred signs make a fairly good sign talker.

(A number of secondary sources state erroneously that Private George Gibson knew sign language and that on one occasion it caused friction between him and Drouillard. The root of this canard appears to be M.O. Skarsten’s biography of Drouillard, which mentions “Gealousy” between the two men recorded by Sergeant John Ordway in his journal entry for 28 November 1804, when the expedition was camped among the Mandans. Ordway refers cryptically to “Gealousy between Mr Gisom one of our Intr. and George Drewyer last evening &C.” Skarsten took “Gisom” to mean Gibson, but the reference is actually to René Jusseaume, a civilian interpreter employed by the captains at Fort Mandan.)[26]Woodger and Toropov, 157 and 182; M.O. Skarsten, George Drouillard: Hunter and Interpreter for Lewis and Clark and Fur Trader, 1807–1810 (Spokane, Washington: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1964 and 2003), … Continue reading

Conclusion

Signing has other advantages besides universality. It can be employed face-to-face or at a distance, beyond ear shot.(Lewis could have conversed with the mounted Shoshone warrior and the Piegan who “came within a hundred paces” at the Two Medicine site.) It can also be used for silent communication when stalking game or sneaking up on an enemy.[27]The examples are drawn from Seton, xxxiii–xxvi; and Garrick Mallery, “Sign Language among North American Indians,” in J. W. Powell, First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the … Continue reading

Conversely, sign language has limitations. It can’t be used in the dark.[28]Unless you have a moonlit night, of course, or “repair to the campfire.” Tylor, 77. And as Lewis observed, it is “imperfect and liable to error.”[29]Moulton, 5:88. There were tribal variations—in effect, dialects—in signing vocabularies, which could lead to confusion, and even the best sign talker would have been challenged to convey some of the abstract concepts about nationhood and political hegemony in the captains’ standard speech to tribal leaders. This may be why Lewis and Clark never relied on signing when they had the option of oral interpretation, even if it meant using long, cumbersome, and time-consuming translation chains.[30]Thompson, 151–154.

Lewis once described the “curses” of his travels as equal to the plagues of Egypt. His difficulties with native languages recall another Biblical metaphor—the Tower of Babel. The Corps of Discovery encountered many languages during its 28 months on the trail, and a lot of what was said—whether by hand or tongue—was probably lost in translation. Yet as always, Lewis and Clark managed. They looked, listened, and talked their way as best they could (all in all, with remarkable success) across a continent and back.

More Examples

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert R. Hunt, “Eye Talk, Ear Talk: Sign Language, Translation Chains, and Trade Jargon on the Lewis & Clark Trail”, We Proceeded On, August 2006, Volume 32, No. 3, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol32no3.pdf#page=13. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 5:88. Entry for 14 August 1805. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text are from Moulton, by date, unless otherwise indicated. |

| ↑3 | The Comprehensive Index (Volume 13) of the Moulton edition of the journals lists 12 references to sign language (not counting notes), all in Volume 5. There are 13 references if you include “signs” made by an excited Sacagawea to Clark on August 17, 1805, when she recognized an approaching band of Indians as Shoshones, her people. The index neglects to list Lewis’s entry of 26 July 1806 (Volume 8, p. 130), which describes his meeting with the Piegan Blackfeet on Two Medicine River [See Fight on the Two Medicine.] |

| ↑4 | William Philo Clark, the first systematic chronicler of Plains Indian sign language, commented on the general paucity of information about the subject in accounts by early explorers and fur traders: “That we find no positive evidence of the existence and use of gesture speech does not necessarily show that there was none. … Circumstances forced Lewis and Clarke [sic.] in their exploration of the then unknown West to spend the winter of 1804–5 with the Mandans, Gros Ventres [Hidatsas], and the Arickarees [Arikaras] in their village on the Missouri … . During the winter the Cheyennes and Sioux visited this village, and there can be no doubt that gesture speech was daily and hourly used by the members of these tribes … but no mention is made of the fact, and not until these explorers met the Shoshones near the headwaters of the Missouri do we find any note made of signs being used. If these explorers who entered so minutely into the characteristics of the Indians in their writings failed to make a record of this language, I do not think it very surprising that earlier investigators should have, under less favorable auspices, also neglected it.” William Philo Clark, The Indian Sign Language (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982; reprint of the original edition, published in Philadelphia by L.R. Hammerly in 1885), p. 11. |

| ↑5 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents: 1783–1854, 2nd. ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:552–553. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 2:563. |

| ↑7 | The Biddle edition (whose nominal editor was Paul Allen) is actually a paraphrased narrative of the expedition based on the journals. In his description of meeting the Shoshones, Biddle did not include Lewis’s comments about Drouillard’s signing. The edition of the journals edited by Elliott Coues in 1893—an annotated update of Biddle—has no more to say about sign language than the Biddle edition. Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, 3 volumes (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1965; reprint of 1893 edition). |

| ↑8 | Ernest Thompson Seton, Sign Talk (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1918), xv. |

| ↑9 | Sir Edward Burnett Tylor, Researches into the Early History of Mankind (London: J. Murray, 1878, 3rd. ed., revised), 3. |

| ↑10 | Jackson, 1:272–274. |

| ↑11 | Ibid., 274–275n2. |

| ↑12 | William Tomkins, Indian Sign Language (New York: Dover, 1969), 63. |

| ↑13 | U.S. Department of the Interior, Plains Indian Sign Language (Browning, Mont.: A Memorial to the Conference 4–6 September 1930), unpaginated. |

| ↑14 | George Fronval and David Dubois, Indian Signals and Sign Language (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 1978), 6. (1985 editions published by Wing Books and Bonanza Books. Originally published in French as Les Signes mysterieux de peaux rouges). |

| ↑15 | Moulton, 5:88n and 224n; Sally Thompson, “Misnomers along the Lewis and Clark Trail,” a paper delivered at a 2003 symposium and published in A Confluence of Cultures: Native Americans and the Expedition of Lewis and Clark (Missoula: University of Montana, 2003), 153; Fronval and Dubois, 17. At the time of their encounter with Lewis and Clark, the Salish no longer practiced head-flattening. The Nez Perces, who call themselves the Nimi-pu, dispute the notion that they ever pierced their noses. |

| ↑16 | Seton, xxvi. |

| ↑17 | Moulton, 5:196–197. |

| ↑18 | Ibid., 69 and 78–79; entries for 11 August 1805 and 13 August 1805. |

| ↑19 | James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984; First Bison Book printing, 1988), 239. |

| ↑20 | Whatever the reason, the encounter ended disastrously. Lewis’s party and the Indians camped together that night. A scuffle broke out the following morning, resulting in the death of one and possibly two of the Blackfeet. |

| ↑21 | Moulton, 10:149; entry for 26 July 1805. |

| ↑22 | Ibid., 149. In this tight situation Clark sensed a need “to prevent Suspission” while trying “to Collect by Signs as much information as possible.” The friendly testimony of a Nez Perce may have done more to allay “suspission” than Clark’s signing efforts; tribal tradition holds that a woman named Watkuweis saved the explorers’ lives. Ronda, 159. |

| ↑23 | Clark, who was again in the lead when they met the Walla Wallas, tells how, to little avail, “I gave my hand to them and made Signs of my friendly disposition.” The Indians were in an agitated state and remained so until they saw Sacagawea and her infant, Pomp, and realized this wasn’t a war party. (Moulton, 5:305–306.) |

| ↑24 | On two other occasions while on or near the Pacific—14 November 1805 and 9 December 1805—the explorers recorded Indians attempting to communicate by “Signs,” but the references are clearly to impromptu body language. |

| ↑25 | Moulton, 5:296. |

| ↑26 | Woodger and Toropov, 157 and 182; M.O. Skarsten, George Drouillard: Hunter and Interpreter for Lewis and Clark and Fur Trader, 1807–1810 (Spokane, Washington: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1964 and 2003), 247–248; Moulton, 9:99. |

| ↑27 | The examples are drawn from Seton, xxxiii–xxvi; and Garrick Mallery, “Sign Language among North American Indians,” in J. W. Powell, First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1879–80 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1881), 312. |

| ↑28 | Unless you have a moonlit night, of course, or “repair to the campfire.” Tylor, 77. |

| ↑29 | Moulton, 5:88. |

| ↑30 | Thompson, 151–154. |