As no man is born an artist so no man is born an angler.

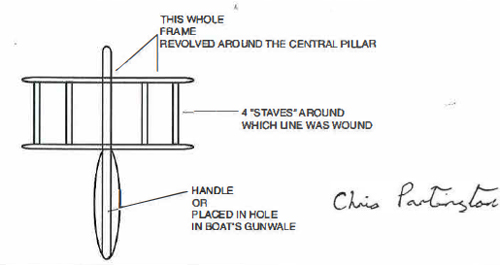

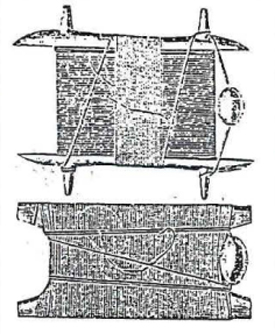

Stave Reel

by Chris Partington

Lewis’s Reel not a Real Reel

The bill of sale endorsed by Captain Lewis in May 1803 in Philadelphia for the purchase of fishing tackle included an item listed as “8 stave reel.” To find a description or an illustration of a stave reel of the Lewis era we contacted a number of students and hobbyists interested in historic fishing gear. The prevailing opinion through these contacts was that equipment of this sort at that time would have been produced in England and exported to dealers in the United States such as George Lawton in Philadelphia. For further information, we were referred to Mr. Chris Partington of Shrewsbury, Shropshire, Great Britain, a specialist in “old fishing tackle, angling art, and literature.” Mr. Partington has been kind enough to comment in response to our inquiries, in part, as follows:

. . . rods and reels did not come in to general use until about 1780 . . . . I feel sure that the stave reel mentioned was a type of winder to store line on. Certainly, during the 19th century winders like the one drawn by me below were used by Cornish sea fishermen fishing with long lines and the list of fishing tackle in . . . [the] 1803 bill of sale is all long line stuff, not rod and line stuff.

Captain William Clark recorded the high moment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition on 7 November 1805: “Ocian in view . . . great joy in Camp,” he wrote.[3]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 1991) Vol. 6, pp. 33 and 58. All quotations or references to journal entries in … Continue reading The Corps of Discovery had finally reached the Pacific, culminating l8 months of severe trial and hardship. Clark’s memoir on this joyful day contrasts curiously with the absence of any such expression from Meriwether Lewis. There is no record whatever from Co-Captain Lewis, the originally designated leader of the corps, of his impressions on first viewing the sea. For him the occasion may have been an anticlimax. Three months previously he had already “seen” the Pacific—from hundreds of miles inland.

On 13 August 1805, after the initial contact with the Lemhi Shoshones in their mountain retreat on the Lemhi River, a hospitable Indian gave Lewis “a piece of a fresh salmon roasted.” This was “the first salmon I had seen,” he wrote, “and perfectly convinced me that we were on the waters of the Pacific Ocean . . . .” His foretaste of the ocean, high in the mountains, relieved Lewis of anxiety in achieving the long-awaited object of his journey. But this roasted salmon was not only a token of discovery; it was also the forerunner of countless numbers of salmon and other fish, of great variety and manner of preparation—boiled, smoked, fried, pounded, dried, fresh and spoiled—over the next full year of the expedition. It was the prelude of a love-hate relationship with fish.

Fishing Tackle

Lewis knew before embarking on his mission that there would be a pack of fish in his future. In Philadelphia in the summer of 1803, preparing for the expedition, he visited the “Old Experienced Tackle Shop” kept by George R. Lawton, a dealer in “all kinds of Fishing Tackle for the use of either Sea or River . . . .”[4]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1978) Vol. 1, 79-95. Lewis purchased there 125 “Large fishing Hooks” plus ten pounds of assorted fishing lines, and an additional 2800 fish hooks for Indian presents; also an item listed as “8 stave reel.” (See accompanying sidebar.) Thus equipped, the expedition was seemingly prepared for many fishing exploits which are recorded in its journals.

Catfish

Generally, on the Ohio and Missouri rivers, the fish stories are about catfish. Lewis was surprised, for example, on 16 November 1803 “at the apparent size of a catfish which the men had caught” near the confluence of the Ohio and the Mississippi. Accustomed to seeing these fish from 30 to 60 pounds in weight, Lewis took dimensions of this trophy. He reported it as 4 feet 3¼ inches in length, weighing 128 pounds. “I have been informed,” he added, “that these fish have been taken in various parts of the Ohio & mississippi weighing from 175 to 200 lbs weight.” From Camp Dubois near St. Louis up the Missouri to Fort Mandan (North Dakota), catfish were everywhere, waiting to be caught and free for the taking.

Private Goodrich

During the catfish episodes, Private Silas Goodrich emerged as the preeminent fisherman of the corps. On 17 July 1804, near present day Peru, Nebraska, Clark reported Goodrich caught “two verry fat catfish.” A week later Goodrich took a “white catfish” which Clark described as having “eyes Small & tale much like that of a Dolfin”—probably the channel catfish, a newly discoveblue species.[5]Moulton, Vol. 2, 418. Goodrich also was one of three men with Lewis on 10 June 1805, during Lewis’s search for the Great Falls of the Missouri. How did Private Goodrich salute that historic discovery?—with fish!—”half a douzen very fine trout and a number of both species of the white fish!” Moreover, among Goodrich’s catch was an additional species new to science, the westslope cutthroat trout—Salmo clarkii, after William Clark. No wonder Lewis reported that “Goodrich … is remarkably fond of fishing,” and on 24 August 1804 dubbed him “our principal fisherman.”

Other Anglers

Aside from Lewis and Goodrich, the journals say very little about any other fishermen in the corps. Sacagawea gets mention at the Great Falls portage; recovering from an alarming illness she was “walking about and fishing.” And by Sgt. Ordway’s report of 15 August 1805, Captain Clark was, while fishing, “near being bit by a rattle Snake which was between his legs.”[6]Ibid, 9:203 Later near the mouth of the Columbia, Clark took 2 “salmon trout” on 12 November 1805. But he says he “killed“[7]Where words are in italics, within quotations from Lewis and Clark journal references in the foregoing text, the italics have been added by the author herein. these fish. Would a bona fide fisherman speak so murderously of fish? Did he use a club, or gunshot? Was there no sport? No hook, line and sinker? Captain Lewis was more relaxed while fishing. With him it was an “amusement.” On his approach to the Great Falls, 12 June 1805, he wrote:

This evening I ate very heartily and after pening the trasactions of the day amused myself catching those white fish mentioned yesterday . . . . ! caught upwards of a douzen in a few minutes; they bit most freely . . . .

Salmon Ahead?

Decomposing Salmon

Brushy Fork, Lolo Trail

© 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Lewis and Clark crossed the Brushy Fork on 14 September 1805 as they passed between their camp on Glade Creek and their island camp on the Lochsa River at present Powell, Idaho. The above photo was taken near that crossing on 10 September 2009. —ed.

Beyond the Great Falls, Lewis and Clark had fewer moments for any amusement such as fishing. They had previously learned from the Mandans that the Snake (Shoshones) and Flathead tribes near the Continental Divide lived “principally on a large fish which they take on the river on which they reside.” The captains surmised that on the Columbia this “large fish” could provide a staff of life such as the buffalo provided in the plains. Thus, when Lewis actually tasted his first salmon with the Shoshones he had come to the expected moment of a new dependency—centered on fish rather than on the guns of his hunters.

But this new dependency soon proved uncertain, even doubtful. The Shoshones warned him that the Snake River, the expected way west, “afforded neither Salmon nor timber.” More worrisome yet, he found on 23 August 1805 that the Shoshones were “haistening from the country” because the salmon has “so far declined”—this when his provision was “so low that it would not support us more than ten days.” Under this pressure, after dickering with the Shoshones for horses, the Corps plunged into the rocky reaches of the Bitterroot Mountains. No fish, no game—the men survived only on blind luck and “killed colts.” Breaking out of this no-man’s-land, they entered upon the drainages which would lead to the Columbia. There on the headwaters they encountered signs of the native fish economy which would govern their days, directly and indirectly, while on the Pacific side of the continent.

The Fish Economy

At this new stage of the journey, the Corps was forced to rely on fish in the diet—fish which was almost always dried, not fresh. On 17 October 1805, near the confluence of the Snake and the Columbia, Clark found himself in the midst of the production process for this basic staple. He observed “emence quantities of dried fish”—large drying scaffolds strung with fish , piles of salmon lying all about, and many women splitting and drying the crop. It was here also that Clark recorded a dramatic, even historic moment. In an air of bewilderment, he wrote:

I observe . . . great numbers of salmon dead on the shores. floating on the water and in the Bottom which can be seen at the debth of 20 feet. The cause of the emence numbers of dead salmon I can’t account for . . . . I must have seen 3 or 400 dead and maney living . . . .

Without knowing it, Clark unconsciously had made, perhaps, the first written record of one of the great mysteries of natural history: the spawning stage in the life cycle of the columbia salmon, its “final seasonal climacteric,” as Paul R. Cutright describes it.[8]Paul Russell Cutright, Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1969) 225.

Clark was witnessing the defining feature of human life on the Columbia. The salmon cycle conditioned all aspects of native culture from the cradle to the grave; to the corps, however, it was inexplicable. Clark’s puzzlement over the “emence numbers of dead salmon” reveals how he (and anyone else of his milieu) was “totally unfamiliar with the life history of this important fish.”Ibid; even in the 1990s the mystery of what impels this mass migration challenges observers. Cf. Keith C. Petersen and Mary E. Reed, Controversy, Conflict and Comprovise: A History of the Lower Snake River Development (Walla Walla, Wash. 1994; p. 94) cf. “Sport Fishing on the Columbia River” by Lisa Mighetto, Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Winter 1995/96, Vol. 87 No. 1, p. 6. See also “Swimming With Salmon” by Jessie Maxwell, photographs by Nathalie Fobes, in Natural History magazine, 5eptember 1995, pp. 26 et seq., esp. 31.

In the presence of this mystery, Clark’s concern was more immediate and practical—the food supply for his companions and the need to hurry further downstream. Despite the abundance of salmon all around him, he wrote that “the fish being out of season and dieing in great numbers in the river, we did not think proper to use them.” Instead, the corps resorted to purchasing dried fish from the native tribes at periodic stops on the river. The explorers then saw firsthand how salmon governed the natives–their occupations, trade, housing, diet, family relationships and cultic rituals, all in a rhythm of seasonal movement up and down the waterways.

In the eyes of Captain Lewis, the fish culture made a difference in the treatment of women. He observed as a “general maxim” (6 January 1806) that the tribes on the Columbia paid more respect to the judgment of their women, as compared with tribes of the hunting economy on the Great Plains where women and old people were treated with least attention. On the Pacific side, women participated in tribal livelihood more actively, assisting in taking and drying the salmon, gathering roots and storing the provisions.

In addition to shaping the mundane habits of the natives, salmon also furnished a spiritual dimension. Lewis noted on 19 April 1804 (near The Dalles), “great joy with natives last night in consequence of the arrival of the salmon; one of those fish was caught; this was the harbinger of good news to them.” It was the annual native occasion for the “first salmon ceremony.” This first fish, Lewis recorded, “was dressed and being divided into small pieces, was given to each child in the village.” To Lewis the custom was “founded in a supersticious opinion that it will hasten the arrival of the salmon.”[9]Moulton, Vol. 7, 142. Ethnologists later wrote that the ceremony had more basic significance. Erna Gunther for example, in her analysis of these rituals,[10]Erna Gunther, A Further Analysis of the First Salmon Ceremony (University of Washington publications in Anthropology, V.2, No. 5, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1928) 166/67. Also Gunther … Continue reading described such main characteristics as:

- an attitude of veneration, based on “belief in the immortality of the salmon and the conscious will of the fish in allowing himself to be caught”

- a feeling that “the salmon is a person, living a life very similar to that of the people who catch him, that in honoring the first salmon, they are honoring the chief of the salmon.”

Famine

Lewis and Clark, however, never witnessed the full, real-life drama of the salmon cycle. They had the misfortune, both descending and ascending the Columbia, to miss the huge salmon runs of the Columbia Basin. In the autumn of 1805 the corps arrived too late to take fresh salmon; in the spring of 1806, the party advanced upstream too early—traveling always just beyond the early fish migrants. The land of salmon became a land of famine, at least of the fresh variety. Scarcity had commenced soon after first crossing the divide. While scouting the Lemhi in last August 1805, Clark’s party was “hourly complaining of their retched Situation and [contemplating?] doubts of Starveing in a Country where no game of any kind except a fiew fish can be found.” When the corps finally stumbled out of the Bitterroots into Nez Perce country, the men lived on “dried sammon” and quamash roots acquiblue from the natives, a continuing ration, for the next nine months.

Fish Diet

The fish diet was disastrous; it worked on the men “much as a dose of salts.” 21 September 1805, Clark: “l am verry Sick to day and puke which relive me.” Lewis was so sick he was “Scercely able to ride on a jentle horse . . . . Several men So unwell that they were Compelled to lie on the Side of the road for Some time . . . .” The journals bear an oft-repeated refrain: “nothing to eate except dried fish and roots.” The men preferred the flesh of dogs, purchasing all they could from native tribes whenever available (40 dogs on one day’s march!)[11]Cutright, p. 21 9. For an extended and engaging account of the diet and food supply on the expedition, see Albert Furtwangler, Acts of Discovery: Visions of America in the Lewis and Clark Journals … Continue reading

Dried fish was a reserve food of last resort. The party carried a store of it downriver from Celilo Falls all the way to winter quarters. Used when nothing else was available, it was “our Standing friend,” as Clark wrote on 1 December 1805 (though not so “friendly” the next day when he complained “have entirely lost my appetite for the Dried pounded fish . . . the cause of my disorder at present.”) On Christmas day, in the expedition’s newly constructed fort, “spoiled fish and pore elk” served as a “bad Christmas dinner.”

But why was the dried salmon reserve so often referred to as “spoiled?” It had been acquired at the Falls of the Columbia (near present day [Dallesport or The Dalles), “that great meeting and trading site,” as Moulton notes, “for the tribes of the Columbia.”[12]Moulton, Vol. 5, 326. Clark observed there on 22 October 1805, how carefully the natives prepared the fish for market. There were “great numbers of stacks of pounded Salmon (butifully) nearly preserved” in lined baskets secured tightly together by corded mats. “Thus preserved,” Clark wrote, “those fish may be kept Sound and Sweet Several years.” Either the expedition was unable to acquire any of these packages, or if so, could not have maintained them carefully enough to keep the fish “sound and sweet.” The reserve was “pore” and “spoiled” at Fort Clatsop.

Fish Feasts

Despite the many anxious days of hunger and ill effects, fish was sometimes a luxury when cooked in singular ways. Westbound, near the Clearwater junction with the Snake, Clark’s party was treated to a special serving of salmon, ceremoniously prepared by a native householder. Clark wrote that this “boiled fish . . . was delicious.” A few days later, one of the men gigged a “salmon trout” (a steelhead). The camp cook fried it in bear’s oil—”the finest fish I ever tasted,” Clark wrote. He was just as eloquent later at Fort Clatsop. After dining on “a Small fish cooked in Indian Stile by roasting” Clark thought them “Superior to any fish I ever tasted.” Lewis chimed in with superlatives for yet another style of native cuisine—vapor or steam cooking. “We live sumptuously,” Lewis wrote at Fort Clatsop, “on our wappatoe and Sturgeon;” when steamed these entrees were “much better than either boiled or roasted.” Just before the party vacated Fort Clatsop, Chief Comowoll presented the captains with a new delicacy—”anchovies” (actually eulachon, i.e. candle fish). Lewis found these “excellent.” On this fare, he wrote, “we once more live in clover.”

Salmon Timetable

Leaving winter quarters on 23 March 1806, the explorers toiled upriver, homeward bound; life in clover had ended. The men promptly resumed their purchase of dogs. On 1 April 1806, near the Willamette River, they met groups of natives who had exhausted their winter store of dried fish, and were “much streightened . . . for the want of food.” These people reported that the tribes further up were equally troubled; “they did not expect the Salmon to arrive untill the full of the next moon which happens on the 2nd of May.” On this alarming intelligence, travel plans gave way to the salmon forecast.[13]While at Fort Clatsop contemplating the homebound voyage Lewis wrote on 14 March 1806 that “the Indians tell us that the Salmon begin to run early in the next month*; it will be unfortunate for … Continue reading Lewis expressed:

much uneasiness with rispect to our future means of subsistence. above falls or through the plains from thence to the Chopunnish [i.e. the Nez Perce] there are no deer Antelope nor Elk on which we can depend for subsistence; their horses are very poor most probably at this season. and if they have no fish their dogs must be in the same situation. under these circumstances there seems to be but a gloomy prospect for subsistence on any terms; . . . it was at once deemed inexpedient to wait the arrival of the salmon as that would detain us so large a portion of the season that it is probable we should not reach the United States before the ice would close the Missouri;

The captains “determined to loose as little time as possible” in rejoining their Nez Perce friends and recovering their horses for repassing the mountains, horses being “our only certain resource for food.”

Thus, began on April 1st a cruel game of hide-and-seek with salmon. From The Dalles to the mountain passes in June, the explorers heard rumors or saw actual evidence of the proximity of the migrating fish, yet the salmon were never within their reach. Was the salmon “chief” of Indian lore persisting in an April fool’s joke? Expedition journals recount weekly, sometimes daily frustrations of hope that the salmon would soon show up. Travel became a two-month seesaw of vain expectations:

| 1-11 April 1806: | natives observed moving upstream to fishing places “though the salmon have not yet made their appearance” |

| 19 April 1806: | The first salmon arrived near The Dalles—expect “great quantity” in five days. |

| 3–4 May 1806: | The last of the dried meat and the “ballance of our Dogs” were consumed—no mention of a fish reserve. nothing left for the morrow. |

| 10 May 1806: | Lewis ordered his famished men to cease begging for fish and roots from the natives. |

| 14 May 1806: | Campsite established within 40 paces of the river, “convenient to the salmon which we expect daily;” |

| 18 May 1806: | Private LePage took a salmon from an eagle, giving “hope that the salmon would shortly be with us.” |

| 21 May 1806: | “We cannot as yet form any just idea what resource the fish will furnish us.” |

| 27 May 1806: | “The dove is cooing which is the signal as the indians inform us of the approach of the salmon” |

With no luck on the Clearwater, the captains commissioned Sergeant Ordway with two men 27 May to visit the Snake River (supposedly only a half day’s ride from camp) to try to garner some of the great numbers of fish reported on that stream. Missing for five days, Ordway finally turned up carrying 17 salmon and some edible roots. But the fish were nearly spoiled by the rugged 70-mile horseback ride. Ironically, Ordway’s party had not caught these fish; they were purchased from the natives! At this, Lewis threw in the towel, 3 June 1806:

I begin to lose all hope of any dependence on the Salmon as this river will not fall sufficiently to take them before we shall leave it, and as yet I see no appearance of their running near the shores as the indians informed us they would in the course of a few days.

By 22 June 1806 the local natives had finally begun to reap the salmon harvest. But it was then time for the corps to attack the mountains. As a last gasp at fish, Private Whitehouse was dispatched to a native village to procure what he could “with a few beads which Captain Clark had unexpectedly found in one of his waistcoat pockets.” Beyond this there was no further waiting for fish.

Fishing Know How

In the land where salmon was king, the corps had survived on dogs, roots and “pore game.” Such fish as the party consumed, whether fresh or dried, had largely been purchased from or donated by the natives. In contrast with experience on the Missouri, the explorers by their own efforts on the Columbia caught very few fish.[14]There were indeed a few notable exceptions where the party did have conspicuous success. For example, when with the Shoshones on 22 August 1805 Lewis “made the men form a bush drag, and with it … Continue reading Not that they didn’t know how. They carefully observed enroute many different fishing methods which sustained a widespread Indian population. Their journals describe a range of native fishing habits including use of:

- weirs, i.e. traps or dams

- gigs, i.e. “bayonets on poles”

- nets, scoop dips, small seines, and drags

- trolling aboard canoes

- beach scavenging

- and, of course, the customary hook on a line on a pole—(the explorers themselves added a further bizarre method of their own: they once shot a salmon when no game was available on the Lemhi!)

Being thus familiar with native methods, the explorers also had ample means for success. Their baggage included thousands of fish hooks and other fishing equipment. Yet all this served more for currency in trading than for taking fish. Fish hooks, in particular, helped purchase not only roots, dogs, beaver and other skins, but also provided wages for native river pilots and even on occasion procured fish (though dried, not the biting kind!).

Incompleat Anglers?

The journals leave the impression that as anglers, for their own edification and sustenance on the Columbia, the men of the corps simply did not score. Partly, no doubt, disinterest was due to distaste for a fish diet. Primarily however, defeat came from being at the wrong places at the wrong times. Nevertheless, despite these failures, the fishing annals of the explorers do provide evidence of importance to the world of angling and natural history: the Corps of Discovery through journal data is credited with identifying and describing 12 species of fish “new to science.”[15]Cutright, Appendix B re Fishes, 425/27 for a catalogue of fishes “discovered by Lewis and Clark” listing 12 different species cross-referenced by source of description in various … Continue reading—not such a shabby record after all! Considering this and the other overall achievements of the expedition, Lewis and Clark, aside from the salmon famine, were indeed at the right place at the right time.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert H. Hunt, Fish Feast or Famine: Incompleat Anglers on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, We Proceeded On, Volume 23, No. 1 (February 1997), the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original printed format is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol23no1.pdf#page=4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Izaak Walton, The Compleat Angler; or, The Contemplative Man’s Recreation. Being a Discourse of Fish and Fishing for the Perusal of Anglers, orig. pub. 1653 (reprint edition, New York: The Heritage Press, I948) author’s Preface. |

| ↑3 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 1991) Vol. 6, pp. 33 and 58. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text are from Moulton, Volumes 1- 9, by date unless otherwise indicated. without further citations in these notes. |

| ↑4 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1978) Vol. 1, 79-95. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, Vol. 2, 418. |

| ↑6 | Ibid, 9:203 |

| ↑7 | Where words are in italics, within quotations from Lewis and Clark journal references in the foregoing text, the italics have been added by the author herein. |

| ↑8 | Paul Russell Cutright, Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1969) 225. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, Vol. 7, 142. |

| ↑10 | Erna Gunther, A Further Analysis of the First Salmon Ceremony (University of Washington publications in Anthropology, V.2, No. 5, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1928) 166/67. Also Gunther in American Anthropologist, n.s. 2B, 1926, pp. 605-617. “Analysis of First Salmon Ceremony.” |

| ↑11 | Cutright, p. 21 9. For an extended and engaging account of the diet and food supply on the expedition, see Albert Furtwangler, Acts of Discovery: Visions of America in the Lewis and Clark Journals (Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1993), Chapter 5 “Ingesting America,” 91-109. |

| ↑12 | Moulton, Vol. 5, 326. |

| ↑13 | While at Fort Clatsop contemplating the homebound voyage Lewis wrote on 14 March 1806 that “the Indians tell us that the Salmon begin to run early in the next month*; it will be unfortunate for us if they do not, for they must form our principal dependence for food in ascending the Columbia, above the falls and its S.E. branch to the mountains.” [*i.e. in April in the zodiac sign of Pisces. the fish . . . .] |

| ↑14 | There were indeed a few notable exceptions where the party did have conspicuous success. For example, when with the Shoshones on 22 August 1805 Lewis “made the men form a bush drag, and with it in about 2 hours they caught 528 very good fish. most of them large trout”! (He distributed “much the greater portion . . . among the Indians.”) This experience however was certainly unusual in the fishing annals of the expedition while “on the waters of the Pacific Ocean.” which for the most part tell of disappointments compounded. |

| ↑15 | Cutright, Appendix B re Fishes, 425/27 for a catalogue of fishes “discovered by Lewis and Clark” listing 12 different species cross-referenced by source of description in various expedition journal compilations, also citing place and date of observation and/or capture. See also Moulton, 5:407/415 for summaries written by Lewis and Clark during the winter at Fort Clatsop regarding species they reported having met on their journey. |