Sheheke—”Big White” (1807)[1]Lewis commissioned a portrait of Sheheke (Big White) and one of his wife Yellow Corn for his projected edition of the journals, but he did not write the book after all, and the portraits were not … Continue reading

by Charles B. J. F. de Saint Mémin (1770–1852)

Elizabeth DeMilt Fund, Collection of the New-York Historical Society Museum

Chalk and charcoal on pink paper on canvas, 22-3/8 by 17 inches. #1860.95.

Sheheke’s Wife, Yellow Corn (1807)[2]The artist himself erroneously labeled the portrait, at the left edge, jeune indienne des iowas du missoury—“Indian girl of the Iowas of the Missouri.” Ellen G. Miles, Saint-Memin and … Continue reading

by Charles B. J. F. de Saint Mémin

Elizabeth DeMilt Fund, Collection of the New-York Historical Society Museum

Pencil and charcoal on paper, 21-1/4 by 15-1/4 inches.

According to an observer at a New Year’s Day celebration at Washington City in 1807, Yellow Corn had “pretty features, a pale yellowish hue, bunches of ear-rings, and her hair divided in the middle, a red line running right across from the back part of the forehead.”[3]Ibid., p. 146.

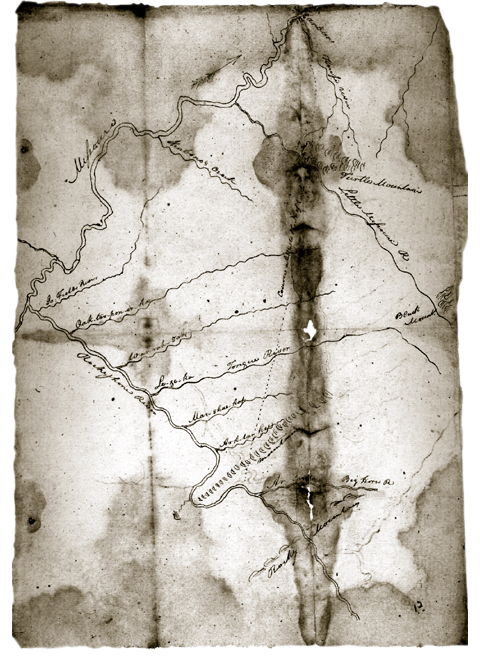

Sheheke’s Map

To see labels, point to the image.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

During the winter at Fort Mandan, Clark drew this sketch from information provided by the Mandan chief, Sheheke, or “Big White,” who dined with the captains on 7 January 1805, and gave him “a Scetch of the Countrey as far as the high mountains, & on the South side of the River Rejone [Roche Jaune; Yellowstone].” Clark added, “he Says that the river rejone recves 6 small rivers on the s. Side, & that the Countrey is verry hilley and the greater part Covered with timber, Great numbers of beaver &c.” Gary Moulton has concluded that some of the tributaries were added to the map after Clark covered the route in 1806.[4]Moulton, ed., Atlas, map 31b.

The comprehensive map Clark compiled at Fort Mandan that winter shows “The War Path of the Big Bellies Nation” extending westward from the mouth of the Knife River and Crossing the Yellowstone at the mouth of O’Fallon Creek (Coal Creek, or Oak-tar-pon-er). It is impossible to say whether this was supposed to be identical with the route shown on Sheheke’s map, because Clark drew both from Indian information before he explored the ground personally.

Sheheke (“White Coyote”), the principal chief of the lower Mandan village, Matutonka (or Matootonha), was nicknamed “Big White” by an unknown white man, evidently because of his size and relatively fair complexion.

On October 20, 1804, two Mandan leaders, each considering himself the principal chief of Mitutanka, came to visit the captains. Having missed the previous day’s meeting, they asked the Americans to repeat their speeches. “They were gratified,” Clark reported, “and we put the medal on the neck of the Big White to whome we had Sent Clothes yesterday & a flag.” The captains meant well, but as usual they acted hastily, and only worsened an enmity they would have to deal with later. Furthermore, they had sealed a relationship with Sheheke (Big White) that would bear bitter fruit. Upon their return in late August of 1806, Sheheke reaffirmed his friendship, and promised that his people would “Shake off all intimicy with the Seioux and unite themselves in a strong allience and attend to what we had told them &c.” Amid good feelings all around, they smoked, and took a walk together. “The Mandan Chief,” Clark observed, “was Saluted by Several Chiefs and brave men on his way with me to the river.”

Trip to Washington City

The captains were eager to fulfill Jefferson’s wish to show Indian leaders the advantages of American culture and civilization. At the Mandan village, there was a noisy argument among several of the chiefs over who would accompany Meriwether Lewis and William Clark back East—or rather, who had the courage to defy the Sioux gatekeepers downriver. The issue was settled by the resident trader, interpreter and able mediator René Jusseaume. Sheheke of the Mandans would go if Jusseaume would go too, and each could take his wife and children. It was late in the afternoon of 17 August 1806 when Clark went to Sheheke’s lodge, to find him “Sorounded by his friends. The men were Setting in a circle smokeing, and the womin Crying.” The captains shared a pipeful of tobacco with the “Grand Cheifs of all the Villages,” listened to the Mandans’ declarations of peace and friendship, and put eighteen miles behind them before making camp.

Four days later they met two traders who passed on some more unwelcome news. The Arikara chief, Piahito [Too Né (Eagle Feather)], also known as Arketarnashar (“Chief of the Town”), who had been a friend and peacemaker in the captains’ behalf the previous spring, was dead. He had sailed south on the returning barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) in the spring of 1805, proceeded on to visit President Thomas Jefferson at Washington City, and succumbed there to a fatal illness.[5]Piahito—”an interesting character,” Henry Dearborn had observed—died on April 7, 1806. On the eleventh Jefferson addressed his condolences to the Arikaras: “On his return to … Continue reading Lewis and Clark had narrowly escaped the retribution of an outraged Arikara community.

Despite the contrarieties of wind and weather, hunger and exhaustion, and a short, bitter exchange of mutual defiance with the Sioux, the men plied their oars with zest, averaging forty miles per day—up to ten times faster than on their upriver trip in 1804. With excitement mounting as the end of the trail drew ever nearer, which of them would have given a thought to the question of getting Sheheke and Jusseaume safely home again?

Planning Sheheke’s Return

On 9 March 1807 Henry Dearborn, Jefferson’s Secretary of War, sent William Clark instructions to see to it that Sheheke and his family were escorted back to their home “by as safe and Speedy conveyance as practicable.” He authorized a small force—one sergeant and ten privates, with the option to add from two to six recruits—to be commanded by Nathaniel Pryor, who had recently been promoted to the rank of ensign (second lieutenant). He also authorized a draft for $400 from the War Department for presents to Sheheke’s people, plus whatever was “indispensibly neccessary in fitting out the party for the Voyage.” Finally, he authorized Clark to grant a two-year monopoly to trade on the Missouri River from the Arikara towns on up, to any merchants or traders who would agree to accompany Pryor’s detachment, and to furnish them with powder and ball for each man. He closed by promising Clark $1,500 per year as the new Agent of Indian Affairs in the Territory of Louisiana.[6]Jackson, Letters, 2:382–83.

Clark promptly replied to Dearborn on May 18 that he had completed all arrangements as instructed, and that Pryor would set out that very evening with fourteen soldiers and an interpreter, plus a trading party of twenty-two under the command of Pierre Chouteau (1786–1838). A frenzy of commercial activity had begun that season, he remarked, with three American companies going up the Missouri, and a group of British traders coming down from Canada, all bound for “the head of the Missouri”—presumably the vicinity of the Knife River towns. He added that Pierre Dorion,[7]Pierre Dorion, Sr. (ca.1750–1810) continued upriver with Pryor after dropping off the Sioux in his party. He had worked for Lewis and Clark in their dealings with the Sioux, and also was to … Continue reading whom the trader and interpreter General James Wilkinson had appointed Indian subagent for the Missouri, had arrived in St. Louis with fifteen Sioux, but that after three days of deliberation the Indians had decided not to proceed on to Washington City to visit the President.[8]Jackson, Letters, 2:411–12

That letter could not have reached Dearborn before Clark dispatched another, on June 1. The group of Sioux, escorted by a lieutenant and seven enlisted men, had already headed homeward on a government boat, evidently satisfied with the presents and treatment they had received. Clark proceeded to explain the plan for Sheheke’s return.

Pryor’s Failed Escort

Five months later, on October 16, Ensign Pryor submitted a 2,200-word report explaining the “untoward circumstances” that led to the failure of his second mission. To begin with, he had been met by a force of about 650 Arikara and Sioux Indians all armed with guns and “additional warlike weapons.” He learned that Manuel Lisa—bound for the Bighorn River on the Yellowstone, with Lewis and Clark veteran John Colter in his party—had passed through some time earlier, and had surrendered some guns and ammunition to the Arikaras. Lisa, perhaps to deflect an immediate attack on his own party, had told the Indians Pryor was coming upriver with Sheheke, and that one of Pryor’s two boats would stop and trade with the Arikaras.[9]Ibid., 2:432–37. Richard Oglesby, Manuel Lisa and the Opening of the Missouri Fur Trade (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 48–50. Pryor was also warned that the Indians had decided to murder the Mandan chief, so he secured Sheheke in the cabin of the boat, and prepared his men for action.

He then tried to persuade “the Arikara,'” thirty-five-year-old head chief, Grey Eyes, to let him pass. “We are not strangers to you,” he reminded the chief. “On a former occasion you extended to Louis & Clark the hand of friendship.” He hung a peace medal around the chief’s neck, promised to stop at the upper village to visit with the other chiefs, and proceeded on. The Indians waved Pryor on, but stopped Chouteau’s keelboat, which contained merchandise and had no soldiers on board to defend it. Confidently, Choteau and a few of his traders stepped ashore to talk.

Grey Eyes defiantly threw his medal on the ground. One of Chouteau’s men was struck with the butt of a gun. A pitched battle erupted. Pryor and Choteau headed their boats downstream in retreat under a hail of bullets from both sides of the river. The battle was abruptly suspended after about an hour when a Sioux leader was killed. Pryor’s detachment suffered three wounded (including George Shannon, whose left leg later had to be amputated), while Chouteau’s party counted four dead and six wounded. “This miscarriage,” Pryor lamented, “is a most unhappy affair.”[10]Jackson, Letters, 2:432–38. Grey Eyes’ son was killed in 1823, in a fight with Missouri Fur Company traders. A few months later the Arikaras retaliated by attacking William Ashley’s fur … Continue reading

Pryor offered to escort Sheheke overland, skirting the combative Arikaras, since his village, Matootonha (or Mitutanka) was only about three days march upriver. However, the chief declined because René Jusseaume, his interpreter, had been badly wounded, and because he was unwilling to risk the safety of their wives and children. He preferred to return to St. Louis where, according to Frederick Bates, he had been “made to believe that he is the ‘Brother’ and not the ‘Son’ of the President.”[11]Ibid., 2:438n. Frederick Bates (1777–1825) became secretary of the Territory of Louisiana in 1807, and was acting governor during Lewis’s frequent absences from his office.

Pryor concluded that if his opinion were asked concerning the optimum force needed to escort this unhappy chief home, he would say at least 400 men, but “surely it is possible that even one thousand men might fail in the attempt.”

Lewis Steps In

Pryor returned in mid-October of 1807, and for the next sixteen months Sheheke and Jusseaume, with their wives and children, languished in St. Louis. On July 17 of the following summer, an exasperated Jefferson asked Lewis what he thought should be done to get the chief and his family back home, and appealed to his patriotism. “We consider the good faith, & the reputation of the nation as pledged to accomplish this,” he wrote.[12]Jackson, Letters, 1:306. Moulton, Journals, 3:175–78, 230–31; 8:311. No reply from Lewis. On August 24 he tried again: “I am uneasy, hearing nothing from you about the Mandan chief, nor the measures for restoring him to his country. That is an object which presses on our justice & our honor.”[13]Jackson, Letters, 2:444–45. But Lewis remained unresponsive for nearly six more months.

At last, on 24 February 1809, Lewis consummated a detailed contract between the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company and himself as the territorial governor and representative of the United States Government, to return Sheheke, Jusseaume, and their wives and children, to their homes at the mouth of the Knife River.[14]Lewis himself had organized the Saint Louis Missouri River Fur Company during the latter part of 1808. The partners included Lewis, his brother Reuben, William Clark, Manuel Lisa, Pierre Chouteau and … Continue reading

The Articles of Agreement stated that for a flat fee of $7,000 the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company would raise a militia of 125 men, to include at least forty expert American riflemen. The citizen soldiers would of course prefer to bring their own weapons if they had them, but the company would furnish at least fifty rifles, plus ammunition. The company was also authorized to engage up to 300 volunteers from “the most friendly and confidential Indian nations,” who would be rewarded with any plunder they could wrest from enemies in any eventual combat. In addition, 105 traders and trappers were to join the force at the Cheyenne River, bringing the total to 550 guns, “a force sufficient not Onely to bid defiance to the Aricares, but to extirpate that abandoned Nation if necessary,” said Lewis. Finally, they were to “arrest those who killed any men under Pryor’s command in September of 1807, and shoot them.”

The armed force would be commanded by Major Pierre Chouteau, a partner of Lewis’s in the Missouri Fur Company. After reaching the Mandan towns and fulfilling its mission, Chouteau’s militia would become a commercial entity with a two-year trade monopoly along the Missouri River between the Platte River and the Knife.

Word got around. A man named Rodolphe Tillier, formerly a factor at Belle Fontaine, Missouri, addressed a complaint to President Madison. “Is it proper for the public service,” he asked indignantly, “that the U.S. officers as a Governor or a Super Intendant of Indian Affairs & U.S. Factor at St. Louis should take any share in Merchantile and private concerns?”[15]Ibid., 2:457n. Nevertheless, Lewis’s plan worked, and after a journey of 101 days, despite some tense moments in getting past the Sioux and Arikaras, Sheheke and his party were delivered safely to their homes on September 24, 1809.

Lewis’s Ultimate Failure

On May 13 Lewis mailed William Eustis, the new secretary of war under President James Madison, a bill for $500 to cover Indian presents for Chouteau’s trip. That letter, historian Donald Jackson points out, “represents the beginning of Lewis’s financial ruin and the events leading to his death.”[16]Ibid., 2:746.

Eustis quickly rejected the claim. Not only had Lewis failed to get prior approval for those items, but he had overstepped his authority at the outset by soliciting volunteers for an expedition that would combine commercial and military objectives, and by appointing Chouteau to command a military unit while he was under appointment to another governmental office. “It is thought,” insisted Eustis, “the Government might, without injury to the public interests, have been consulted.”[17]Ibid., 2:456–57. Another claim that was rejected was for an “assaying furnace” for Chouteau’s use, presumably in evaluating deposits of galena, or lead ore, along his route. Basically, Lewis’s plan had been consistent with the orders Clark had received from Henry Dearborn two years before, but Jefferson’s hip-pocket brand of government would not sell in the strict-constructionist atmosphere of Madison’s administration.

Lewis replied to Eustis on August 18: “Yours of the 15th July is now before me, the feelings it excites are truly painful.” In a crescendo of pain and paranoia he set out on his last journey on September fourth, wrote his last will and testament on the eleventh, and on the sixteenth, in a bleary drunken haze, scrawled a rambling letter to President Madison from Chickesaw Bluffs, begging to be allowed to show him his financial records and explain his actions.[18]Ibid., 2:464. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage, 459–65. “An explaneation is all that is necessary I am sensible to put all matters right,” he assured his friend Major Amos Stoddard on the twenty-second.[19]Ibid., 2:466.

On the morning of 11 October 1809, Governor Meriwether Lewis died of self-inflicted gunshot wounds. He was thirty-five.

Consequences

Because of aggressive interference from Sioux and Arikara warriors, Sheheke’s return home required two attempts in two years, involving a collective force of more than 600 soldiers, cost a total of $20,000 plus four American lives and one limb (of George Shannon), and brought down the careers of at least two great leaders—himself, and Meriwether Lewis. The trip cost him his once respectable reputation among his people, perhaps because of his long absence, but also because his people didn’t believe his tales of the wonders he had seen.

If it is true that Sheheke really wanted to spend the rest of his life among white people, then Jefferson’s policy, as carried out by Lewis and Clark, was vindicated. The irony of his story, however, is that he was killed in his own village by Sioux raiders in 1832.[20]Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin No. 30. 2 vols, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, … Continue reading

Portions of this article were reviewed by Albert Furtwangler

Notes

| ↑1 | Lewis commissioned a portrait of Sheheke (Big White) and one of his wife Yellow Corn for his projected edition of the journals, but he did not write the book after all, and the portraits were not included in the 1814 condensation of the captains’ journals, edited by Nicholas Biddle. Roy E. Appleman, Lewis & Clark: Historic Places Associated with Their Transcontinental Exploration (1804–06) (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975), 377n. The artist himself erroneously labeled Sheheke’s portrait, at the left edge, Indien des Iowas du Missoury—“Indian of the Iowas of the Missouri.” Ellen G. Miles, Saint-Memin and the Neoclassical Profile Portrait in America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 435–36. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The artist himself erroneously labeled the portrait, at the left edge, jeune indienne des iowas du missoury—“Indian girl of the Iowas of the Missouri.” Ellen G. Miles, Saint-Memin and the Neoclassical Profile Portrait in America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 434–35. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., p. 146. |

| ↑4 | Moulton, ed., Atlas, map 31b. |

| ↑5 | Piahito—”an interesting character,” Henry Dearborn had observed—died on April 7, 1806. On the eleventh Jefferson addressed his condolences to the Arikaras: “On his return to this place he was taken sick; every thing we could do to help him was done; but it pleased the great Spirit to take him from among us. We buried him among our own deceased friends & relatives, we shed many tears over his grave, and we now mingle our afflictions with yours on the loss of this beloved chief. But death must happen to all men; and his time was come.” Secretary of War Henry Dearborn made arrangements to return Piahito’s peace medal and other personal effects to his son, along with “something like a commission to him of a Chief.” Two or three hundred dollars’ worth of gifts were sent to Piahito’s wife and children. Needless to say, the words and gifts had little effect, and the Arikaras held the Americans responsible. Jackson, Letters, 1:303, 305–06. Of the forty or so Poncas, Omahas, Otoes and Missourias, Iowas, Pawnees, Osages, who went east that spring, six or seven died there, in addition to Piahito. Jackson, Letters, 2:743. |

| ↑6 | Jackson, Letters, 2:382–83. |

| ↑7 | Pierre Dorion, Sr. (ca.1750–1810) continued upriver with Pryor after dropping off the Sioux in his party. He had worked for Lewis and Clark in their dealings with the Sioux, and also was to accompany Pierre Chouteau on the 1809 expedition to take Sheheke home. |

| ↑8 | Jackson, Letters, 2:411–12 |

| ↑9 | Ibid., 2:432–37. Richard Oglesby, Manuel Lisa and the Opening of the Missouri Fur Trade (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 48–50. |

| ↑10 | Jackson, Letters, 2:432–38. Grey Eyes’ son was killed in 1823, in a fight with Missouri Fur Company traders. A few months later the Arikaras retaliated by attacking William Ashley’s fur brigade, killing Corps-of-Discovery veteran John Collins. Before the year was out, Grey Eyes himself was killed in a bombardment of his village by U.S. Army artillery under Colonel Henry Leavenworth. Moulton, Journals, 8:316–17n. |

| ↑11 | Ibid., 2:438n. Frederick Bates (1777–1825) became secretary of the Territory of Louisiana in 1807, and was acting governor during Lewis’s frequent absences from his office. |

| ↑12 | Jackson, Letters, 1:306. Moulton, Journals, 3:175–78, 230–31; 8:311. |

| ↑13 | Jackson, Letters, 2:444–45. |

| ↑14 | Lewis himself had organized the Saint Louis Missouri River Fur Company during the latter part of 1808. The partners included Lewis, his brother Reuben, William Clark, Manuel Lisa, Pierre Chouteau and his father Auguste, and Benjamin Wilkinson, brother of the notorious General James Wilkinson. Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 444. |

| ↑15 | Ibid., 2:457n. |

| ↑16 | Ibid., 2:746. |

| ↑17 | Ibid., 2:456–57. Another claim that was rejected was for an “assaying furnace” for Chouteau’s use, presumably in evaluating deposits of galena, or lead ore, along his route. |

| ↑18 | Ibid., 2:464. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage, 459–65. |

| ↑19 | Ibid., 2:466. |

| ↑20 | Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin No. 30. 2 vols, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 2:518-19. Tracy Potter, Sheheke, Mandan Indian Diplomat: The Story of White Coyote, Thomas Jefferson, and Lewis and Clark (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003). |