On this day with Lewis & Clark

October 4, 1803

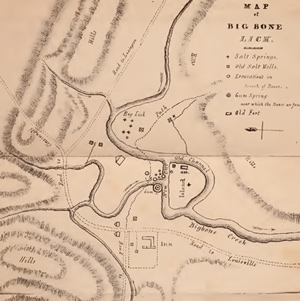

To Big Bone Lick

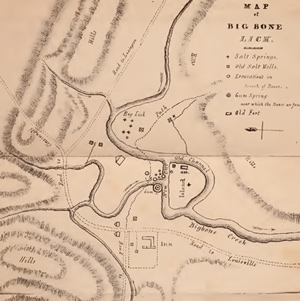

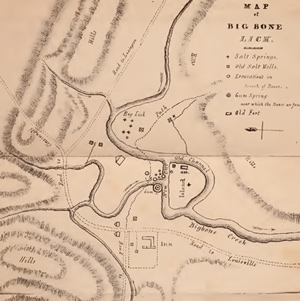

On or near this date, Lewis leaves Cincinnati for Big Bone Lick where he expects to collect fossils for Thomas Jefferson. Elsewhere, tensions rise between Spain and the United States over Louisiana.

More...

October 4, 1804

Turn around

The day begins by dropping back three miles to a better channel. They avoid the Sioux along the banks, and camp across from an abandoned Arikara village near present Forest City, South Dakota.

More...

October 4, 1805

Dried fish and roots

Lewis can finally “walk about a little” at Clearwater Canoe Camp near present Orofino, Idaho. The enlisted men tire of their diet of roots, and a disgruntled Nez Perce man helps himself to some tobacco.

More...

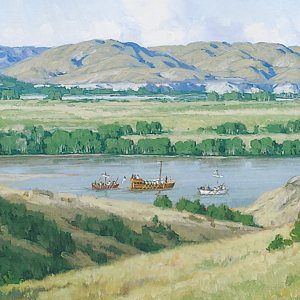

Down the Ohio

31 August–13 November 1803

On 31 August 1803, after months of preparation, Lewis and his crew finally head down the Ohio River. Unfortunately, the water is so low that they must frequently unload and tow the overloaded barge with horses and oxen.

At the request of President Jefferson, Lewis disembarks at Cincinnati and travels overland to gather fossils at Big Bone Lick. He meets the boats, and together they continue to the Falls of the Ohio to pick up William Clark and several new recruits.

The expedition arrives at Fort Massac near the mouth of the Ohio on 11 November. There, they meet George Drouillard and immediately hire him as an interpreter. His first mission is to find the missing army recruits from Fort Southwest Point in Tennessee.

Read more ↓

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

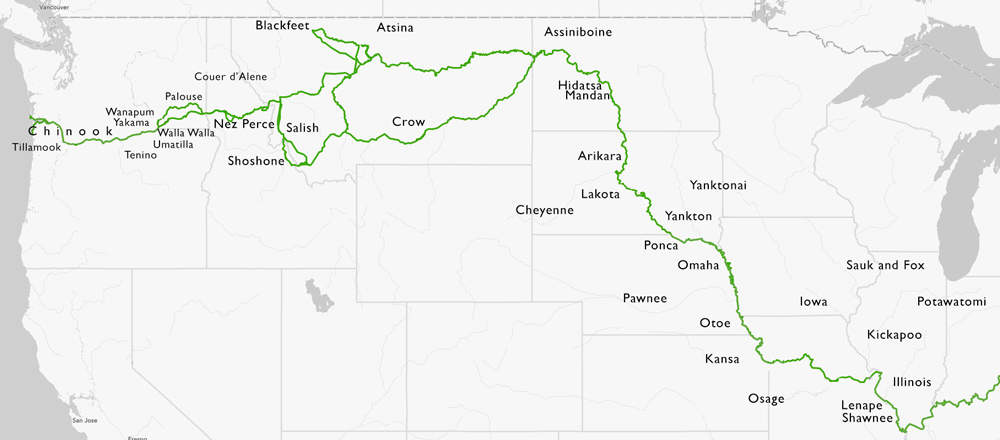

Crossing the Lakotas

9 September–25 Oct 1804

Moving the flotilla of boats up the Missouri in the present states of South and North Dakota, the expedition encounters several nations with limited experience with St. Louis-based traders.

Soon after going around the Big Bend of the Missouri, they meet the Lakota Sioux, and a multi-day encounter goes badly for both peoples. They proceed on to some Arikara villages where they hold a council and invite Too Né (Eagle Feather) to travel with them. He provides useful information and would eventually visit Washington City.

In late October, they reach the Knife River Villages—a complex of Hidatsa and Mandan villages. With winter quickly approaching, they must act fast to establish winter quarters.

Read more ↓

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

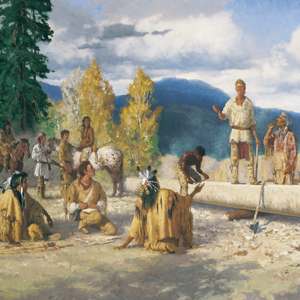

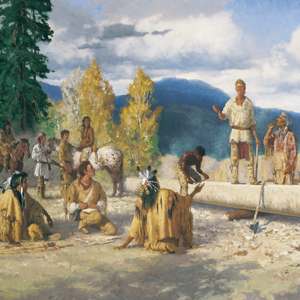

Among the Nez Perce

20 September–17 October 1805

Fatigued and physically sick after crossing the Bitterroot Mountains, the expedition is aided by the Nez Perce. With their help, they find a location on the Clearwater River to build five dugout canoes and employ the Nez Perce method of burning out the Ponderosa pine logs.

The Nez Perce agree to take care of the expedition’s horses while they continue to the Pacific Ocean. Two Nez Perce chiefs volunteer to guide them down the Clearwater and Snake to the Columbia. The guides help scout the rapids and introduce the expedition to the various Nez Perce and Palouse bands fishing in the many rapids.

On 16 October 1805, they negotiate the last Snake River rapid and arrive at the Columbia River where many Yakamas and Wanapums are gathered. About two hundred men approach, singing and beating their drums.

Read more ↓

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

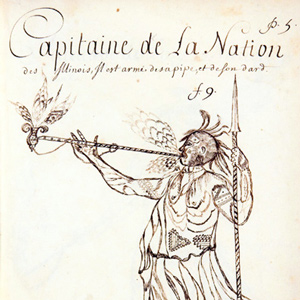

Native Nations Encountered

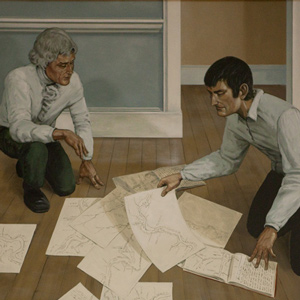

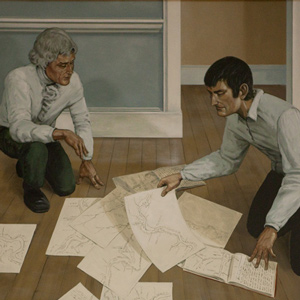

Featured Artist Roger Cooke

Historical artist Roger Cooke worked with the Washington State Historical Society to recreate several Lewis and Clark scenes of their trek in Washington and Oregon. His art is featured on many interpretive signs at waysides throughout this area of the historic trail. Cooke’s works bring people to the forefront of the Lewis and Clark story. His illustrations feature not just the expedition members but Nez Perce, Palouse, Yakama, Wanapum, Walla Walla, Umatilla, Tenino, Wishram, and various Upper and Lower Chinook Peoples. He displays a full spectrum of emotions—even smiling Indians!—and multi-generational families near their villages. These are stories that modern cameras and digital editing cannot capture.

Artist’s Index

More

Starting with its genesis in Jefferson’s Monticello, Lewis’s training and preparations in Philadelphia, and the barge’s excursion down the Ohio River, the route they took, often called the Lewis and Clark Trail, crosses the continent weaving an epic tale of western exploration treasured by many today.

Throughout the expedition the soldiers were expected to conform to the rules and routines of the frontier soldier of 1803.

Legacy is a very slippery sort of term. If we could erase our myth concepts of Lewis and Clark … it might reawaken something really extraordinary in our national consciousness.

Lewis and Clark were among several significant explorers of North America both before and after the expedition.

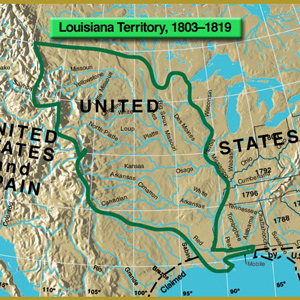

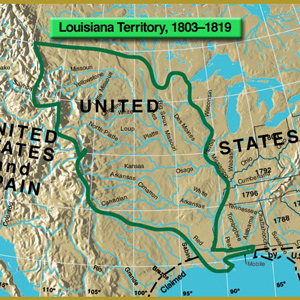

The President’s representatives in Paris had bargained successfully with Napoleon’s bureaucrats not only to buy the port of New Orleans, then the keystone of the continent, but also to acquire, at three cents an acre, an area extending from the Mississippi River to . . . where? No one knew until Meriwether Lewis stood at the crest of the Rocky Mountains at a place known today as Lemhi Pass, on 12 August 1805.

Given President Jefferson’s directive to establish commerce, the captains worked extensively within a long-established network of North American fur trade. Part of their mission was to help establish the United States of America’s position within that industry.

Explore the methods they used to get stuff done—from building canoes to making rope.

The success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was due to its many members and the people they met, including politicians, Eastern gentleman scientists, traders, and the many people already living in the American west.

The entire story is told in these five webpages.

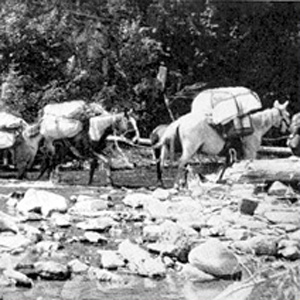

To cross the Rocky Mountains, the Lewis and Clark Expedition needed horses and the skills to manage them. Despite their seemingly constant struggle to find missing and stolen horses, as a kind of calvary unit, they left hoof prints on approximately 1,500 miles of western terrain.

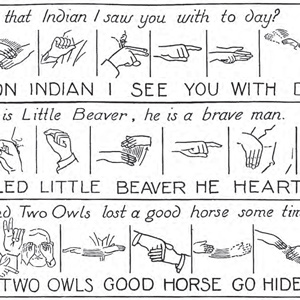

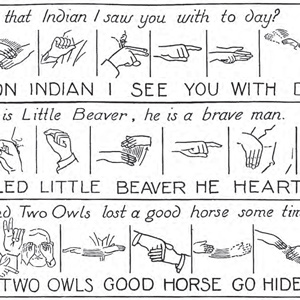

From clichés and colorful sayings of the time to Native American languages, these pages feature the art of language.

Lewis and Clark left behind among many Indians a legacy of nonviolent contact. Those who came later enjoyed that legacy and too often betrayed it.

From major crisis such as the death of Sgt. Floyd, Lewis’s gunshot wound, and the illness of Sacagawea to minor events such as sexually transmitted diseases, mosquito-born illnesses, and deep cuts, the medical aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition provide an interesting topic of study.

Starting at Pittsburgh, traveling to the Pacific Ocean, and then returning to St. Louis, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled approximately 10,600 miles. Of that, 85%—over 9,000 miles—was by boat. To understand travel in the early 1800 American West is to understand the boats and challenges of river navigation.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition benefited from the Indians’ knowledge and support. Maps, route information, food, horses, open-handed friendship—all gave the Corps of Discovery the edge that spelled the difference between success and failure.

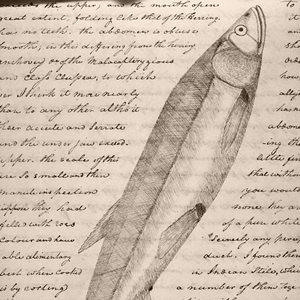

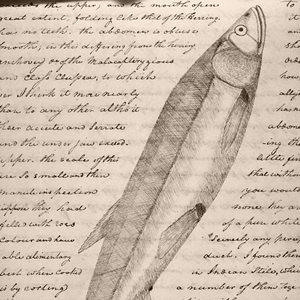

Although hunting and fishing were often considered a ‘gentleman’s sport’ especially in Europe, hunting and fishing for Native Americans and Americans alike were a matter of survival. The success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition depended on the success of its hunters.

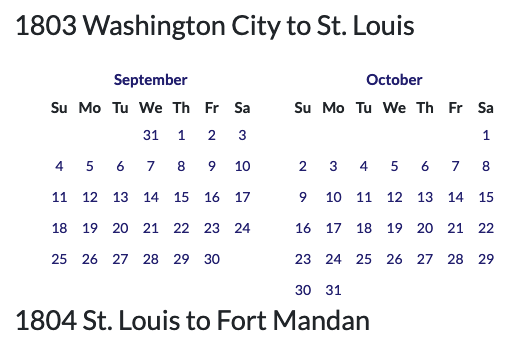

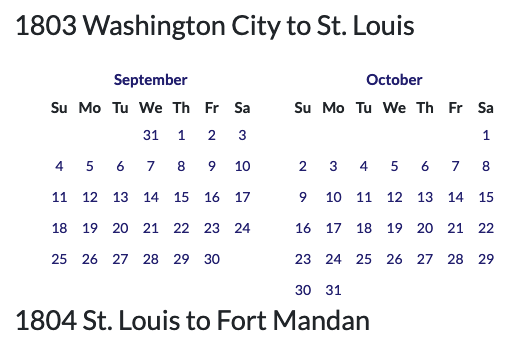

Links to every day-by-day page in a calendar format spanning 31 August 1803 to 26 September 1806. A page every day!

Learn about the people—and one dog—who were members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Other topics include music, holidays, High Potential Historic Sites, and an index of articles from We Proceeded On.

Because of the literate journalists, historians and visual artists can tell the Expedition’s story. When they celebrated with song and dance, we too can share in the experience.

Their work in the emerging fields of botany, ethnography, geography, geology, and zoology are now considered classics of early American scientific literature.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.